The Girl in Red or Heureux Hasard

L. John Harris finds a painting and takes it with him down a rabbit’s hole

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week was a full one, I saw two exhibitions at the Louvre - Louvre Couture and Cimabue. The first seemed an attempt to lure people into less visited collections at the Louvre (Ancient and Byzantine jewelry and decorative arts). And to encourage people whose passion is fashion, to give the Louvre a try. I am not sure they succeeded on either count. The other exhibition focused upon a very recent Louvre acquisition, one of 8 small panels by the father of the Italian Renaissance Art, Cimabue. Only 3 of the 8 panels are extant. This one was found hanging in the kitchen of a house in a Paris suburb. I’ll tell you more about it next week. I also saw an exhibition at the Musée Maillol on the artist Nadia Leger, the wife of Fernand Leger, about whom I knew nothing. Something that, feminist that I am, is embarrassing to admit. But the exhibition catalogue was comforting, it appears I am not alone. The curators suggest that one reason Nadia Leger disappeared from public view is because she was “a devoted member of the Communist Party (and that) the political dimension of her work is central.” Nadia’s resurrection might be imminent now with Trump embracing Vladimir Putin and throwing aside our allies of the past 75 years.

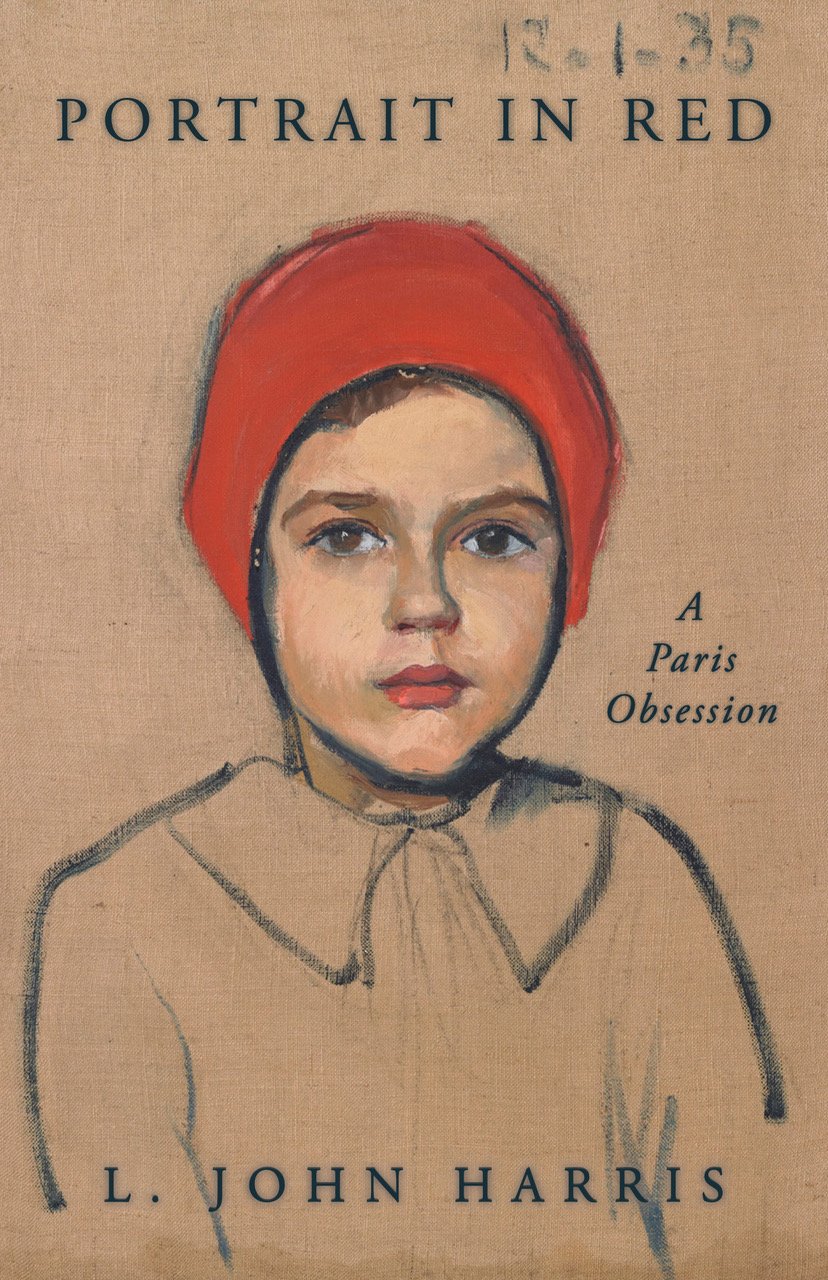

Today is a review of a book by L John Harris, ‘Portrait in Red, a Paris Obsession,’ which I assumed was going to be a book about a painting. I was initially confused by all the digressions. Then I realized that the tangents and caveats were as much the point as the adventure. So, I settled down and enjoyed the ride. I reviewed a book a few years ago, by a man on a quest to see all the paintings by Bruegel the Elder. That book was as much about the author’s traveling companions and the random people he met along the way as it was about the paintings. #1. (LINKS TO ALL #S WHICH REFER TO ARTICLES I’VE WRITTEN ARE AT END OF POST)

I wasn’t sure about some of John’s tangents the first time I read the book. But that wasn’t really a problem, since none of the detours last so long that you get completely lost. And some of them, lots of them actually, either sent me down my own paths of reflection or sent me scurrying after more information about a particular person or perception. And while I‘m at it, I may as well mention that I occasionally became impatient with all the name dropping. Not of people but of streets. Then I realized that local flavor calls for specificity and nothing says this happened in Paris, in the 6th arrondissement like a list of street and place names. And finally, as I was reading, I was contemplating the idea of writing a memoir. And if I did, what particular event should trigger my reveries, should take me into the past and catapult me back to the present.

This is not the first book by this author that I have reviewed. Recently I wrote about John’s ‘My Little Plague Journal,’ an account of what he did to remain (mostly) sane during Covid. That one was introspective, as was mostly everything produced during that time ‘hors temps,’ certainly for those of us who were living alone, pod-less. #2

This book, or at least the ingredients for it, were assembled before those of that other book, in 2015. I met John a few years later, having a café at a café on a random Sunday morning with a random group of people, mostly women, mostly Americans. We got to talking about flaneurs and dandies. John suggested that boulevardiers came before flaneurs. I suggested that boulevardiers (the men, not the drink) could not have been a thing until boulevards. Until that is, the 1860s when Baron Haussmann, appointed by Emperor Napoleon III, brought boulevards to the heart of Paris. It was the kind of conversation smart women have with men who think they are smart(er). It all ended amicably and John gave each of us a poster of a painting, explaining that he had found it a few years earlier and was trying to learn as much about it as he could. (Fig 1)

Figure 1. Poster John had printed to try to find out more about the painting

Here’s the backstory. In 2015, John arrived in Paris with a mission, or at least an assignment from an online publication - to eat croque monsieurs at a variety of Paris cafés and write up his evaluations. A croque monsieur (to remind you) is the French version of a grilled ham and cheese sandwich - the ham usually boiled, the cheese normally grated gruyere and the bread typically pain de mie. I made them often for my kids during the summers we spent in the Dordogne - using supermarket pain de mie, aka Harry’s, the French equivalent of Wonder Bread. Croques are everywhere in this book.

As John was returning to his apartment after eating one of those croques, he notice a pile of stuff, on the sidewalk, leaning against a building. The pile included a painting in a frame. It caught his eye. He picked it up. He looked around. He hesitated for a moment. Then he took it with him. I am more of a cleaner than a gleaner, so I mostly leave stuff I see ‘littering’ the streets where I see it. But I have lived long enough with two artist-gleaners that I am often the recipient of random finds. That was particularly so when Nicolas was in art school. Many of his fellow students were foreign and lots of the stuff they bought to make their stay in dorm rooms or apartments more pleasant weren’t the kinds of things they took home in their suitcases to China, South Korea or Japan. Electronic appliances, clothes and discarded art pieces went from littering Oakland sidewalks to littering my San Francisco garage.

My most recent gleaning experience was with Ginevra, right before Christmas. We were on Anza Street, a few blocks from the Pacific Ocean, on our way to Land’s End (my effort to introduce specificity). We saw a guy on a bike with his young daughter on the seat behind him. They had a cardboard box. I think the box was filled with remnants of a Nativity Scene. I think they were leaving objects randomly on sidewalks for other people to glean. Ginevra thinks that the father and daughter were checking out stuff themselves, to decide what to put into their gleaners’ cardboard box. I guess I could post a sign and ask for information….

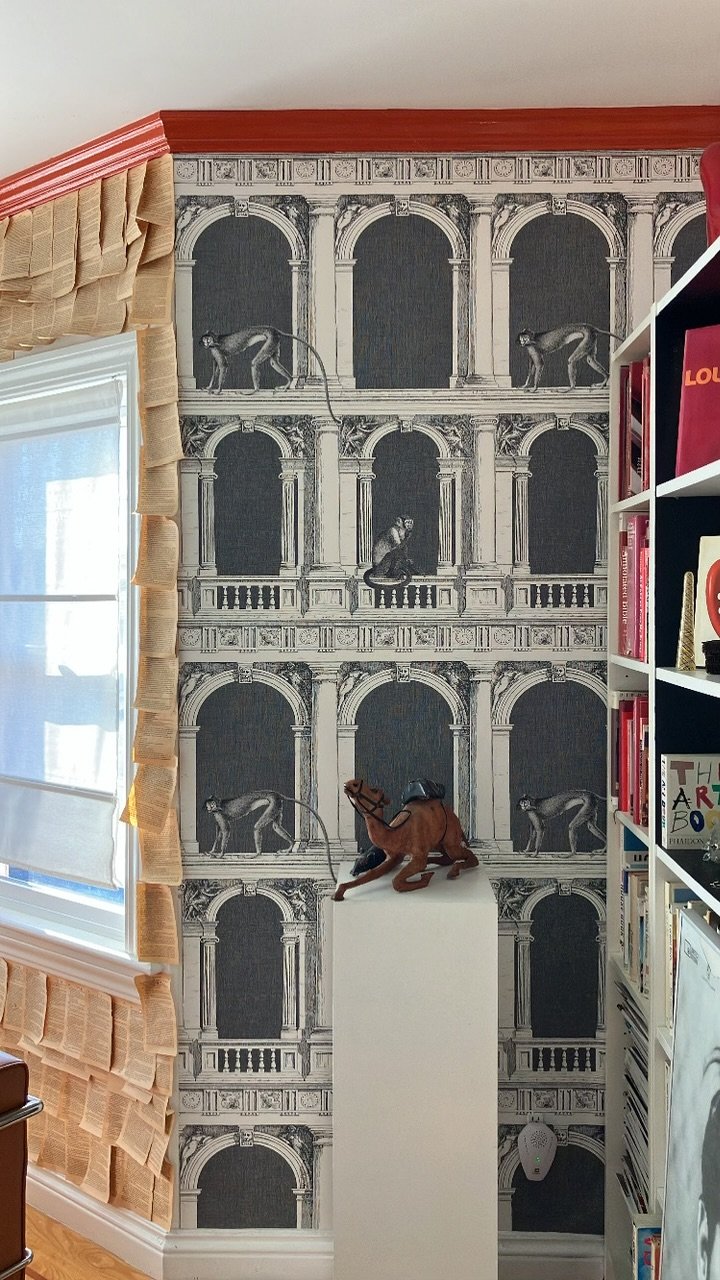

They left (did not to take) two wooden camels with glass eyes and leather, brass and copper (now green) detailing. Each is 12 “ high, one standing, one kneeling. Ginevra wanted to take them. I told her that if they were still there after our walk, it was meant to be. They were and they graced our mantle at Christmas. Now each is on a separate pedestal, guarding a glass rat Nicolas made for a long ago school project (Figs 2, 3)

Figure 2. The Kneeling Camel Ginevra and I gleaned on our walk home from Land’s End, San Francisco

Figure 3. The Standing Camel Ginevra and I gleaned on our walk home from Land’s End, San Francisco

The camels on our Christmas mantle.

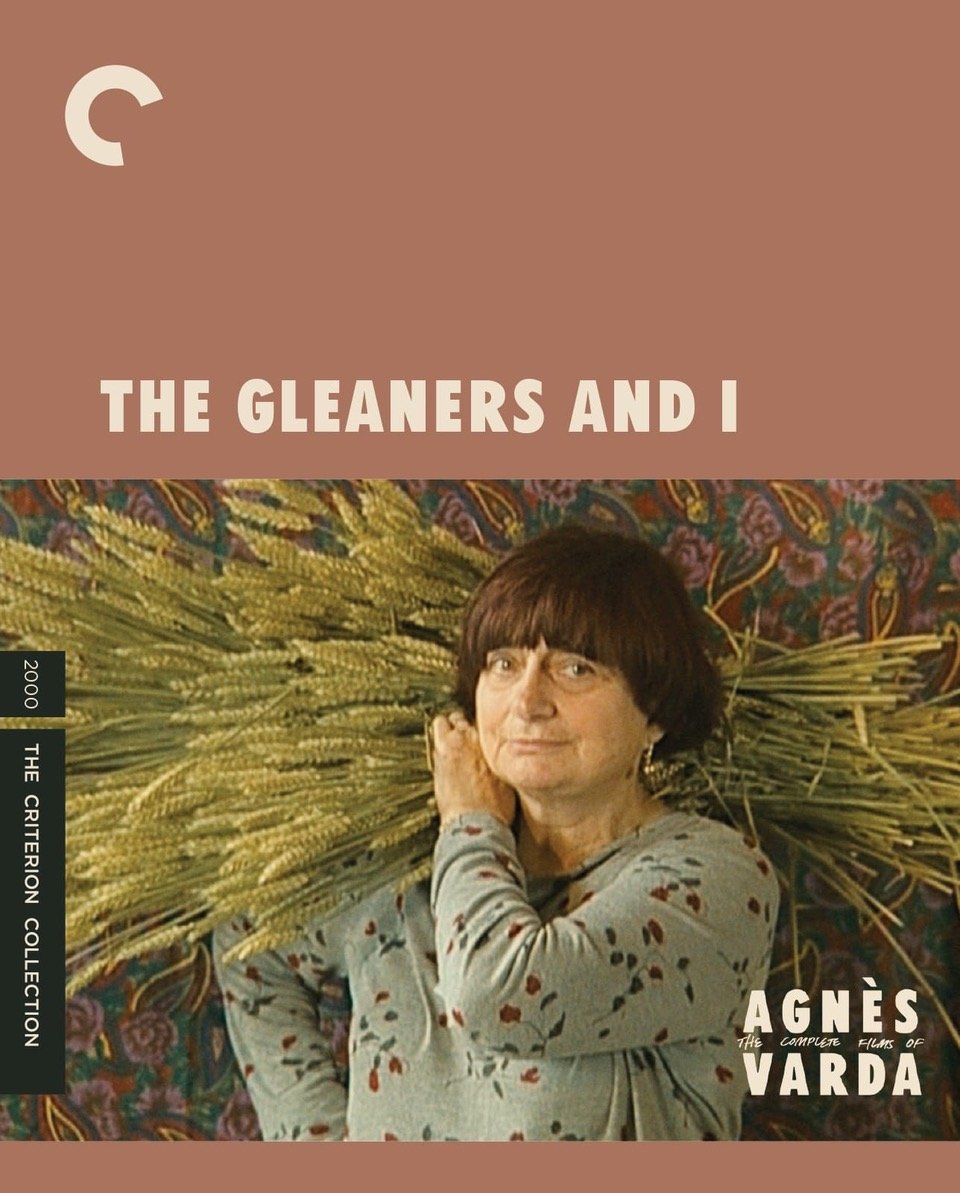

Here’s what John has to say about flaneurs and gleaners in his book. “The Paris flaneur strolls upright, detached from utility (work), seemingly disconnected from the reality around him. He doesn’t consume and he doesn’t stoop; he merely observes. The gleaneur is literally grounded in reality, stooping low to harvest what has been abandoned.” (Fig 4)

Figure 4. The Gleaners, Jean-François Millet, 1857

A lot of what John learned about gleaning is from a 2000 film by Agnes Varda called ‘The Gleaners and I’ (Fig 5) Do you know Agnes Varda? John offers a lot of information about the people he mentions. Kind of like the following - I saw a film by Varda, Cleo 9 to 5 with Nicolas when he was taking a film class at college. In 2017, Varda and the artist JR made a film called Faces Places (Fig 6) about their travels through rural France. The film won an award at Cannes and was nominated for a documentary film Oscar. Right before her death in 2019 (age 90), Varda directed her last film, called Varda by Agnes, in which she emphasized the importance of inspiration, creation and sharing. Since her death, Varda’s face and name have popped up regularly. In 2022, the Cannes Film Festival honored her by naming a room after her. In 2023, two exhibitions celebrated her life and work. From April through August (2025) the Musée Carnavalet will mount an exhibition on Varda. Like here, we get sidetracked in John’s book, but we do learn a lot.

Figure 5. The Gleaners and I, (Les glaneurs et la glaneuse) Agnès Varda, 2000

Figure 6. Agnes Varda and JR for their 2017 film, Faces Places

John’s concern about being a thief rather than a gleaner was laid to rest by a lawyer featured in Varda’s film. According to him, John is the legitimate owner of the painting because ‘an abandoned object has no legal owner until it is claimed.’ For a Jewish writer/outcast/gleaner, that information offered a soothing sense of legitimacy.

As John tries to learn something about the artist who painted this unfinished portrait and his sitter, the numbers 12 - 1 - 35 in the right hand corner of the canvas, loom large. How could they not, knowing what we know now about France in the decade that followed that date. One can’t help but wonder if the artist and sitter were forced to flee the country or go into hiding. Or if they were amongst those rounded up and taken to extermination camps. Or were they, like the people I wrote about in The Propagandist, Nazis or Nazi sympathizers? #3 Or just people like you and me trying to live their lives as we are now, with the threat of a puppet dictator whose strings are being pulled by a ruthless autocrat and an idiot savant?

John offers one theory about why the painting was left unfinished, citing an artist who studied with Michelangelo and had a painting by the master to complete in his own way. But I wasn’t convinced. The finished head and sketched collar and bodice suggested two other possibilities to me. In colonial America, usually untrained and definitely itinerant painters traveled to towns and villages painting faces of people who sat for their portraits. The artist then took the unfinished paintings home with them to complete during the winter. But it wasn’t just those limners who painted faces with a sitter in front of them and left the rest of the painting to be completed at a later time. Court painters like Hyacinthe Rigaud about whom the Chateau de Versailles mounted an excellent exhibition, #4 did the same thing. Sitters would sit only as long as it took for their faces to be finished. After they left, clothing and background would be completed by Rigaud’s associates and assistants. Maybe John’s painting just never got finished or maybe, following another train of thought, it was never meant to be.

When John returned to Paris the following year he continued his search for information about the artist and his sitter. Which is why he had posters of the painting produced that he posted in lots of places. And just like that, the postings became performance pieces, installations, which John photographed. (Fig 7) But that wasn’t the end, he returned to the places he had posted his posters to see if they were still there, and if were, had they been defaced. If they had been removed, he often reposted them and checked back on the new posters in the following days/weeks. Nothing unusual for a guy who studied art at UC Berkeley in the 60s. I wasn’t surprised when John mentioned that he had considered finishing the painting himself!

Figure 7. John’s poster posted with ‘gleanable’ stuff around it

His postings and photographing reminded me of Sophie Calle, the French writer, photographer, installation and conceptual artist. I became obsessed with her when she had a one-person show at the Musée Picasso. I especially admired how she used art to respond to events in her life - a guy leaving her, her mother dying. For the guy who sent her a break-up letter, which ended with the words, ‘Take care of yourself,’ she sought advice from a variety of women, experts in various fields. Their letters responding to his letter was Calle’s subject in the French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2007.(Fig 8) #5

Figure 8. ‘Take Care of Yourself,’ Sophie Calle, French Pavillion of Venice Biennale, 2007

Oh yes, another thing about John is that he keeps bumping into people, in Paris, in London, in Berkeley. The guy who wrote about looking for every Bruegel painting in the world also had encounters. But since he was a married man, his encounters differed from John’s who, as a bon vivant, often had random and planned encounters with a defilé of young women, many of which are documented. His encounters are ostensibly to learn more about his painting. Some of his encounters are strange, some are whimsical. Some of the people are reasonable and some are definitely not. For example, in Paris, there’s the sympathetic artist Yuri Kuper and the very creepy gallerist, who John calls Gilbert, which is definitely not his name and who goes out of his way to derail John when he can.

John’s tangents also take him to books and films on art theory and practice, like the aforementioned film by Agnes Varda. There’s a section on John Berger’s book, Ways of Seeing which was initially a BBC television program that Berger narrated. In a course I called ‘Women as Artists; Women as Art,’ that I taught at the art school my son eventually attended, the reading assignment that generated the most discussion was Berger on Suzanna and the Elders.(Fig 9) About being spied upon, being looked at against one’s will.

Figure 9. Susannah and the Elders, Artimesia Gentelleschi, 1610

And then there was John’s discussion of Walter Benjamin who John talks about in relationship to ‘aura’ which John tells us is an aesthetic concept developed in the 1930s by Benjamin, a German Jewish philosopher and Marxist critic. Auras only exist with original works, not with mechanical reproductions of them. It’s John’s painting that has aura and not the high quality stock posters he had reproduced. John also knows Benjamin because of his work on the poet Baudelaire “the quintessential bohemian artiste-flaneur who worked and virtually lived in cafes.” In the context of Benjamin’s writings, John wonders if Jews can be flaneurs since they have always been outsiders. The answer is decisively no, a flaneur intentionally stays aloof from bourgeois urban culture. The Wandering Jew, the ultimate outsider, doesn’t have a choice.

I know Benjamin as someone who was so immersed in his research on 19th century Paris and the pedestrian passages, his Arcades Project, that he waited too long to flee. He was detained at the Spanish/French border on his way to Portugal and eventually the U.S. Rather than risk being sent back to France and certain deportation to a concentration camp, he committed suicide. He entrusted his writings to one of his companions. Those papers, which cost him his life, have never been found.

Of course Proust pops up. For example, John wanted to name his piece on croques, In Search of Lost Croques’ but his editor refused. Too bad John’s editor wasn’t French, if she had been, she would have insisted upon it. Klimt’s painting, Woman in Gold makes an appearance. John saw it New York on his way to Paris in 2015 and it gave him the idea to name his painting, ‘Girl in Red’. And there’s the College of Pataphysiques that was so much a part of the Musée Carnavalet’s exhibition on the designer, Philippe Starck. #6. Stendhal is here, too. I associate him with Stendhal Syndrome, also called Florence Syndrome. People experience it when they are overwhelmed by a beautiful place or painting. For John, Stendhal appears because of his book, ‘The Red and the Black.’ The painting John gleaned is mostly black lines with red lips and cloche.

On the homepage of my website, I compare looking at paintings to eating this way: “The nice thing about gorging on paintings at an art gallery as opposed to say, gorging on tarts at a patisserie or baguettes at a boulangerie is that there is no remorse, no waves of nausea, that so often accompany those other indulgences. There is just no such thing as looking too long or too lard at a painting.”

Here’s John on dining in a restaurant vs making a painting, ”A meal at a restaurant-when you are done, the plate’s empty, the meal is definitely, unambiguously terminé. In the culinary arts you can have seconds, never again firsts. Creating an oil painting is…more like a journey, an explorer’s voyage across an ocean with an unknown destination, duration and arrival time.”

It’s a good read, so don’t rush it. Pick it up when you have your first glass of wine for the evening. Or when you’ve just returned from an art exhibition. Better yet, when you’ve just come back with your own haul from a yard sale. Or perhaps if you’re considering writing a memoir. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Thanks to those of you who commented on my trip to Normandie, your comments are much, much appreciated.

New comments on A weekend in Normandie

Dr. B Thank you for another fascinating post. I will definitely put Le Havre and Muma on the list for our next trip to Deauville. Sadly we will miss the Senn exhibit but the museum looks wonderful in itself. We visited the Boudin Museum in Honfleur and were not impressed at all...in fact disappointed. Your info on Julie Manet was enlightening and so very interesting bringing to light many things I was not aware of about that family. When we visited Les Franciscaines there were no art exhibits of any interest though we did enjoy the building itself and its offerings. If our mare, residing just outside of Deauville, foals before May, maybe we'll get there in time to see Julie Manet though it will be close. Can't rush her. Ha! Thanks again for a wonderful read! Shirley L.

Another fabulous “lesson” in art and Food. I love the section about the women artists. They are finally getting their due. Deedee, Baltimore & Florida

Links to my articles referenced in the body of the text:

Short life in a Strange World #1

It Depends on what you Pay (Hyacinth Rigaud) #4

Sophie Calle (one of 3 articles on Calle) #5