It’s all in the details

Art at the dawn of the Renaissance, Revoir Cimabue, Musée du Louvre

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. Today’s topic - an exhibition at the Louvre about the dawn of the Renaissance. Art history mixed with a little intrigue and a touch of human interest.

I had a happy, busy week personally and a horribly depressing one philosophically - watching endless clips on French television of good people being browbeaten by ignorant, self serving ones. I saw an opera and an exhibition both seemed to be warnings. The opera, I Puritani by Vincenzo Bellini takes place during the English Civil War (1642-52). (Fig 1) It begins with rivalry, madness and revenge and ends with integrity, decency and love. It’s the last three that are in such short supply these days. The exhibition at the Musée Picasso (Fig 2) is eerily prescient. It’s about the paintings and sculptures in German museums that Hitler and his thugs deemed degenerate - paintings by Jews, Communists, the usual cast of characters. The paintings were rounded up to be publicly ridiculed and then destroyed or sold. It was a frightening and graphic reminder of how easily art can be used to serve the purposes of a dictator bent on control and manipulation. For anyone who imagines that it could never happen in the U.S, you are no more blind than the German people were in 1935. And it has already begun! The Kennedy Center has been cleansed of artistic independence. Art exhibitions by people or groups for whom DEI might apply have been canceled. To be silent is to be complicit.

Figure 1. I Puritani, Vincenzo Bellini, Opera de la Bastille

Figure 2. L’Art Dégénéré, Musé Picasso Paris

Back to my happy week. It included another walk with my friend Melinda. She hates the heat, so she loves Paris in the winter. And when she goes home in April, she gets winter all over again, especially in August, in San Francisco. She and her husband walk a lot and since they live nearby (in Paris), a lot of the places they go are ones I know. Thanks to Melinda, I’ve been learning new routes to and from familiar places. And this week, I was introduced to a new boulangerie. As I told Melinda, I’m a loyal person so I wasn’t prepared to love the bread at Archibald’s as much as I did. Melinda’s favorite, meteil (rye) and Arnie’s favorite, integrale (whole grain) took enjoying the cheeses I brought back from Normandie to another whole level. (Fig 3)

Figure 3. Archibald Boulangerie, rue des Fossés Saint-Bernard, Paris

At the Maison Victor Hugo on the Place des Vosges I saw an exhibition on the work of an artist who, after a promising start (he was awarded the Prix de Rome and spent 5 years in Italy learning from the great masters of the Renaissance) just couldn’t get any traction. That seems to be the theme running through a spate of exhibitions I’ve seen recently. Albert Marquet, collected by Olivier Senn, who should be a household name but isn’t, Paule Gobillard, Julie Manet’s cousin, who exhibited her work but doesn’t seem to have sold much. And now, Francois Chifflart whose masterpiece is stored at the Petit Palais but didn’t merit the cost of cleaning for this exhibition. It was a sad tale, demonstrating that timing is just as important as talent. And that sometimes the only luck is bad luck. Chifflart’s large scale paintings on grand themes and the engravings he made to illustrate Victor Hugo’s book, Toilers of the Sea, are well worth seeing. (Figs 4-6).

Figure 4. The Return of Odysseus (Ulysses), François Chifflart

Figure 5. ’Toilers of the Sea,’ by Victor Hugo illustrated by François Chillart

Figure 6. A video discussing Chifflart’s masterpiece which was not prepared for this exhibition

Now about the exhibition at the Louvre. It's the latest in the series the Louvre calls ‘Revoir’ or ‘A New Look.’ It’s about looking at familiar works of art and seeing them in a new way. One previous ‘Revoirs’ focused on a restored painting by the 15th century Flemish artist Jan van Eyck and a second, on ‘Pierrot’ by the French Rococo artist, Antoine Watteau. (Figs 7, 8) The exhibitions are timed to celebrate a painting after conservationists have painstakingly restored a painting to its original vibrance.

Figure 7. Revoir Van Eyck, Louvre

Figure 8. Revoir Watteau

The focus may be on a single painting, but it doesn’t stop there. It’s more like a pebble being thrown into a pond. We follow the ripples to gain a greater understanding of the painting’s cultural and art historical context. The exhibitions are held in a few small rooms off the beaten path. And while it’s never easy to navigate the endless corridors of the Louvre, once you make it past the guards for the timed entries to these exhibitions, you can relax and enjoy yourself, there’s no jostling, no pushing, no selfie-sticks.

Have you ever taken an Intro to Art History course? I hope that if you have, the course unfolded chronologically. When Ginevra took it at Berkeley, it was taught thematically. Such a mistake! Themes need history. Berkeley’s focus on ‘isms’ lost it at least one good student - my daughter. See, I can be old fashion and reactionary, too!

First semester art history courses start at prehistoric art and end at medieval art. Second semester begins with the proto-renaissance in Italy. I taught that course many times over the years. Just as often, I taught courses focused solely on Italian Renaissance Art. I admit that I lingered on Giotto, especially the Arena Chapel in Padua, paid for by a son hoping to expatiate the sins of his father’s usury. The physical and emotional realism of Giotto’s figures were the touchstone for western artists until the Impressionists. Who decided that if photography offered realism, their paintings needed to offer something else. And yes, Proust loved Giotto and the Arena Chapel, too. (Figs 9, 10)

Figure 9. Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Giotto, Padua, a jewel box of a space with three bands of narrative, the closest is the Passion of Christ, normally placed the farthest away from the viewer, here placed the closest.

Figure 10. The Crucifixion of Christ, Mary Magdalene at Christ’s feet, the Virgin swooning in sadness, the angel to the right of Christ, ‘renting’ his garment in mourning, Giotto, Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua

Here’s a true story about my experience teaching Italian Renaissance Art. It was a week-long course through an organization called Elderhostel, (now Road Scholar.) The class met everyday for two hours. After four days, a couple stopped payment on their check and left, offended by all the Christian images I had shown. It’s not easy. (Fig 11)

Figure 11. Virgin and Child with Angel, Botticelli (Isabelle Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). The Angel holds a bowl filled with grapes and wheat, a reference to the blood and body of Christ, the Holy Eucharist. This is what we call a Prefiguration. The Virgin reaches for the wheat, showing that she accepts Her Son’s destiny

The story of Italian Renaissance Art History begins before Giotto of course. He didn’t spring from the head of Zeus like Athena or from the foam of the sea like Aphrodite. Giotto had a teacher named Cenni di Pepo, (1240-1302) about whom we know very little, including (according to the curators of this exhibition) the meaning of his nickname Cimabue. It probably means bull-head/ed. A dozen paintings have been attributed to him, as well as a fresco cycle in Assisi and mosaics in Florence and Pisa. (Figs 12, 13)

Figure 12. Crucified Christ, Cimabue, Assisi,

Figure 13. St. Francis holding a book, his garment torn, revealing the wound of the Stigmata on his chest. The hole in each hand also refers to the Stigmata. Cimabue, Assisi

Cimabue’s just restored Maesta is the centerpiece of this exhibition. (Fig 14) The theme was well known, The Virgin and Child on a throne, surrounded by angels. Like Byzantine icons, Cimabue’s scene takes place in Holy space, the background is gold. (Fig 15) Two sets of three angels seem to float on top of each other rather than behind one another. Halos are solid disks which would certainly discourage any one of these figures from turning around. In traditional Byzantine fashion, the Virgin’s eyes are almond shape, her nose is aquiline, her lips are pressed closed, her face is narrow. She tilts her head, better to hear the Word of the Lord. The Christ Child, sits on her lap with His fingers raised in blessing, looking more like a miniature 10 year old, than a babe in arms.

Figure 14. Maestá, Cimabue, Louvre

Figure 15. Virgin Mary with Christ Child, Byzantine icon

And yet, and yet, the painter emphasizes the individuality of the Virgin and the angels. Each is dressed differently, each has fingers with joints. Look closely at the Christ Child. He is holding a scroll in His hand. It indents with the pressure of His fingers, it yields realistically to His grasp. Look more closely still and see the tunic covering the Child’s legs, it’s diaphanous, you can see His knees, His legs. In this painting, figures and their clothing belong to our world. “Cimabue was one of the first painters who sought to represent the world as he observed it.” (Figs 16 - 19)

Figure 16. Maesta, detail Lower right corner, Angels’ different color robes and jointed fingers.

Figure !7. Maesta, detail, Christ Child holding scroll, Madonna & Angel with jointed fingers, Cimabue, Louvre

Figure 18. Maesta, closer detail, Christ Child holding scroll, Cimabue, Louvre

Figure 19. Maesta, detail of Christ Child’s legs visible under diaphanous garment, Cimabue, Louvre

Thomas Bohl, the curator of this exhibition contends that the journey from medieval art to Renaissance art could not have been made without Cimabue. He inherited the rigid Byzantine style of flat backgrounds and static figures. But he pushed beyond those constraints to create visual narratives with backgrounds that hinted at depth and figures that hinted at both anatomical accuracy and human expression.

Cimabue’s Maestà clearly establishes that the sweet, Byzantine tradition exemplified by the Sienese artist, Duccio. (Figs 20, 21) and the muscular Florentine tradition, exemplified by Giotto (Figs 22, 23) began with Cimabue. Those two artists took elements from Cimabue and expanded upon his innovations in their own way. Duccio was a contemporary, Giotto was a pupil. The apocryphal story is that Giotto was a shepherd boy of 10, when Cimabue discovered him drawing images of sheep on a rock. Giotto became Cimabue’s apprentice and eventually eclipsed his master. That story was first told by their contemporary, Dante in his “Divine Comedy.” The poet, imagining a brief encounter with the painter in purgatory, observed that, “In painting Cimabue thought he held the field but now it’s Giotto has the cry, so that the other’s fame is dimmed.” In the beginning was Cimabue and he was good, but his pupil, Giotto, was better.

Figure 20. Maesta, Duccio

Figure 21. Annunciation (Angel Gabriel tells Virgin that she is with Child), Duccio, National Gallery, London

Figure 22. Ognisanti Madonna, Giotto. All bodies have weight, the Virgin sits on throne, the child sits on her knees and the angels kneel on real knees, too

Figure 23. Comparison between Cimabue’s Santa Trinita Maesta (NOT Louvre painting), 1290 and Giotto’s Ognisanti Madonna, 1310. Giotto retains some elements of Cimabue but everything has greater weight, depth, solidity

Cimabue’s Maestà was a major commission. Painted around 1280, to be placed on the rood screen (it separated the nave from the choir) in what was then the largest church in Tuscany, the church of San Francesco in Pisa. Where it hung for 532 years. But now it’s in Paris. How did it get from Pisa to Paris? Simple, it was stolen by Napoleon’s army, (Fig 24) under orders from Dominique Vivant Denon, the Louvre's first director. If the name sounds familiar, that’s because it’s the name of one of the wings of the Louvre. Denon took the Maestà and a painting by Giotto, St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata, which was also in Pisa. (Fig 25) And which is also in this exhibition.

Figure 24. Napoleon’s troops enter Venice, ready to plunder

Figure 25. St. Francis receiving the Stigmata (the wound of Christ) a mix of sacred (gold) space and our own - buildings, trees, St. Francis’ robes, Giotto, Louvre

After the fall of Napoleon in 1815, many of the cities and churches from which Napoleon and his army looted artworks, tried to get them back. According to the Louvre, “Italian curators did not request its (the Maestà’s) return, given the contemporary lack of interest in paintings of its period and the projected cost of its transportation.” Welcome to whitewashing! The main difference between the horrific and wholesale looting of art museums by Hitler’s band of thugs and Napoleon’s soldiers is that although Napoleon’s soldiers lost and destroyed many of the works of art they took, it was expediency and stupidity and not vindictive maliciousness that was at fault.

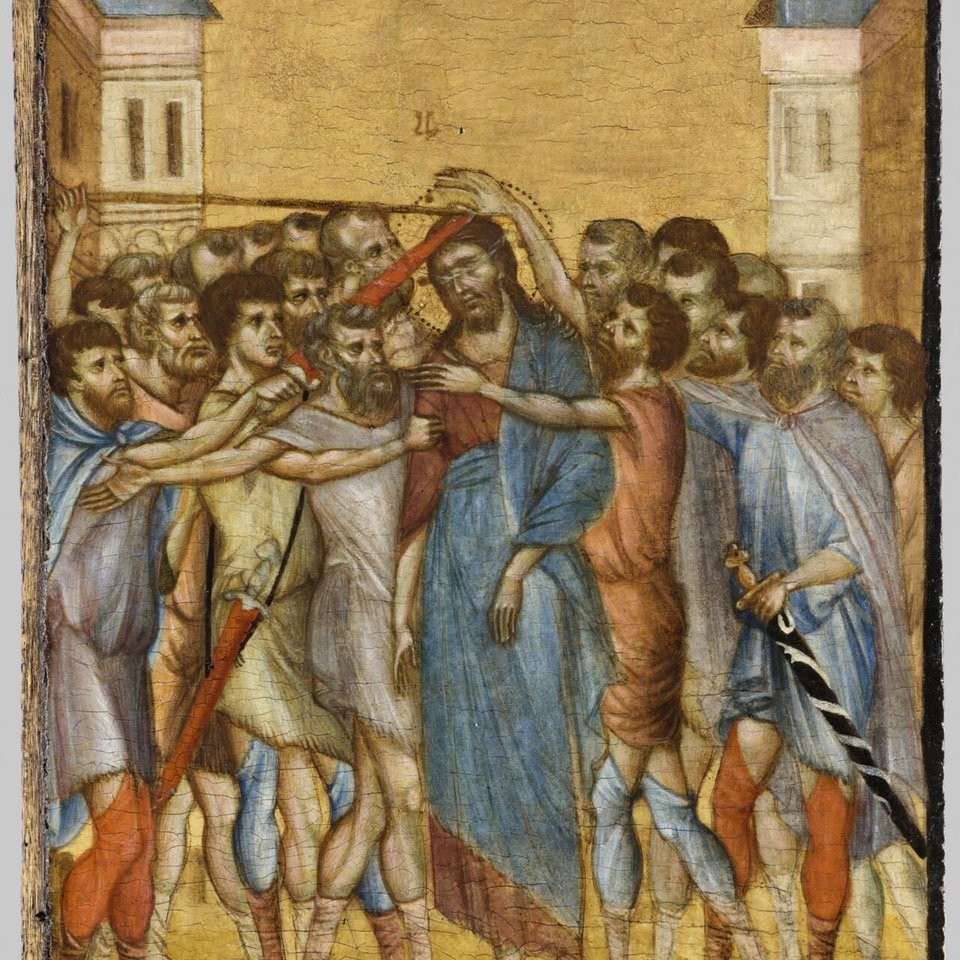

The Maestà wasn’t the only star of this exhibition. There was a second painting, a small panel depicting ‘The Mocking of Christ,’ (Figs 26, 27) which shows a blindfolded Christ being struck and abused by an angry crowd. Here the background isn’t solid gold anymore. The men reaching out to hit Christ are all different - expressions, hair, even clothes which are contemporary to Cimabue’s own time. The arms of the men in front are muscled, tensed, articulated. As with the works of Giotto and Duccio at this time, Cimabue was influenced by the Franciscan Order founded by St. Francis of Assisi in 1209 which promoted a spirituality based upon everyday life.

Figure 26. Mocking of Christ, Cimabue, Louvre

Figure 27. Mocking of Christ, Cimabue, Louvre - before cleaning (NYT, 2019)

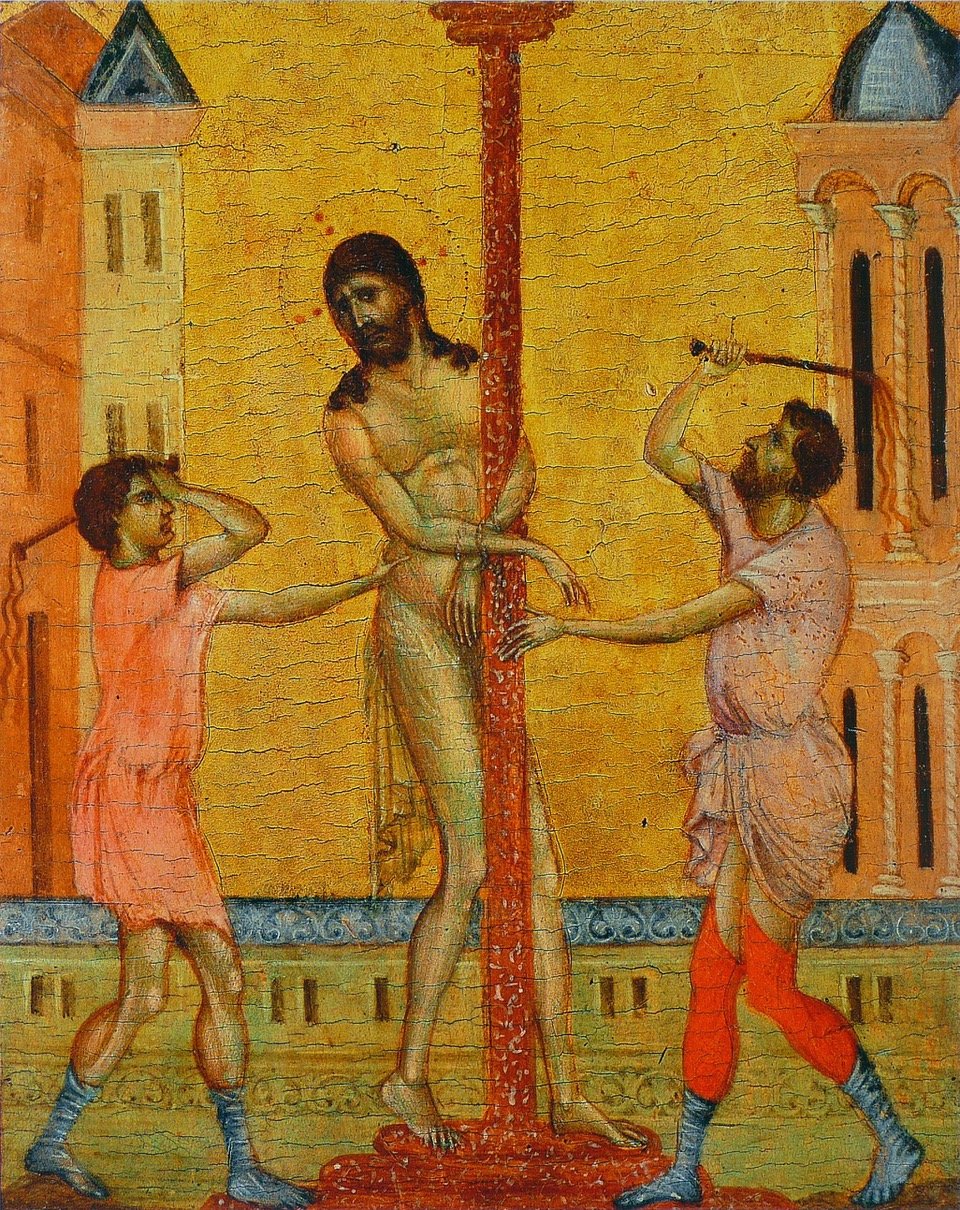

The panel is one of eight painted in the 1280s, the same decade as the Maestà. Experts believe that the 8 panels were separated in the 19th century to be sold individually Only two other panels are known to have survived, the “Flagellation of Christ” at the Frick Collection in New York and the “Madonna and Child Enthroned between Two Angels,” at the National Gallery in London. (Fig 28)

Figure 28. Three surviving panels of original 8, Cimabue

The Frick Collection acquired the painting from the Knoedler Gallery in Paris in 1950 and its provenance (where’s its been) since the 19th century is known. Who painted it, wasn’t initially so clear. It was originally thought to have been painted by Duccio or maybe by Cimabue or his workshop. The uncertainty was resolved when the second panel was discovered and attributed to Cimabue, which led to the attribution of the Flagellation of Christ (Fig 29) to Cimabue.

Figure 29. Flagellation of Christ, Cimabue, Frick Collection, New York

The National Gallery panel was discovered at Benacre Hall in Suffolk in 2000. After its owner Sir John Gooch died, the contents of his house were prepared for auction. The panel was found hanging on a landing. It had gone unnoticed for decades, it had even survived a house fire in 1920. Gooch’s heirs speculate that it was acquired by one of their ancestors in the early 19th century. The panel was put up for sale and was expected to sell for £10 million, but before it could be sold the heirs negotiated with English tax officers to use it to offset some of their inheritance tax.

How the Louvre panel was found is even stranger. In June, 2019, an elderly woman living in Compiègne, north of Paris, was getting ready to move to a retirement home. She called a local auctioneer to see if any of her furniture or furnishings had any value.

“I had a week to give an expert view on the house contents and empty it,” Philomène Wolf told Le Parisien. If she hadn’t been able to fit the visit into her schedule, everything was going to be taken to the dump. Wolf said she spotted the small painting hanging in the kitchen over a hot-plate as soon as she entered the house. “I immediately thought it was a work of Italian primitivism. But I didn’t imagine it was a Cimabue.”

The auctioneer, who started working at the auction house just a year earlier, thought it might sell for €300,000-€400,000. She took the painting to a prominent Paris-based expert who was sure that it was by Cimabue.

The auctioneers who handled the sale didn’t know what the panel might fetch since nothing by Cimabue had ever been sold at auction. So they put a price of €4 - €6 million on it. The US-based Chilean collectors who own the Alana collection outbid the Metropolitan Museum of Art for it. I saw an exhibition on the Alana collection a few years ago at the Musée Jacquemart-André about which I wrote, if you’re collecting Italian Renaissance art now, you don’t get a lot of bang for the buck.

As soon as a foreign buyer bought the panel for €19.5 million (€24 million with fees), the French government blocked the sale, declaring the work a “national treasure”. The culture ministry had 30 months to raise the funds to acquire the panel. Which he did through the generous support of US donors. And that’s how Cimabue’s long-lost “Mocking of Christ” ended up in the world’s most visited museum.

The elderly woman and her relatives, who remain anonymous, had always assumed that the panel was a Russian icon. They have no idea where it came from or how they came to own it. Alas, the elderly woman didn’t appreciate her windfall for long, she died two weeks after the auction. And with the French tax department being what it is, her family had to pay for the work to be insured while the government found funds to purchase it. And since nothing is ever easy or fair in France, even before the funds were found, the family began negotiating inheritance tax payments with tax officials.

I’m not sure what the moral of this story is. As I mentioned last week when I discussed John Harris’ memoir/adventure story, I am more of a cleaner than a gleaner. And I am certainly not a hoarder. Although I suppose I would prefer to be negotiating inheritance tax with the French authorities on €19 million than paying someone to take everything in my house to the tip! Gros bisous, Dr. B.

As always thanks to those of you who had time to read my book review last week. Here’s what L. John Harris thought of the review:

I really like and appreciate your piece. Despite your quibbles, I think you got into the book in just the way I hope readers will--to enjoy the journey as I have, "as it happens." It can seem choppy and helter skelter at times, perhaps, but isn't that how life is? Rhizomatic instead of linear. I liked the way your review becomes your own journey within mine. And just when I thought you would never come back to my book, you did! Your final comment is very nice. Thank you! John, Berkeley

To read the review, click here: