How the day of reckoning finally arrives

“The Propagandist,” Cécile Desprairies

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week, a review of a book I just read for the second time, Cécile Desprairies’ ‘The Propagandist.’ It is the author’s first work of literature but not her first work on this subject, which she, an historian of the Nazi occupation of France, has written about extensively. Her six non-fiction books include titles like, ‘City of Light – Dark Years, the Places of Paris Collaboration’ and ‘The Vichy Legacy - These 100 measures still in force.’ One of those measures is Mother’s Day which became a holiday in 1941, when Marchal Pétain added it to the national calendar. Her book, ‘Journey through occupied France, 1940-1945. 4,000 familiar places to rediscover,’ is not the travel guide I’ll be following anytime soon - make that, ever.

The advance reading copy of The Propagandist arrived at my San Francisco address in May, just in time for Nicolas to bring it with him to Paris. I was going to take it with me to Berlin but decided that wasn’t such a good idea, given that I would be going to, well, Berlin. Back in Paris, I kept getting side tracked - books I was reading for my Book Club, research I was doing for my posts on art exhibitions. Then it was October and I took it with me to Spain to read at night after walking the Camino. But that was a mistake. I needed something spiritual, something up-lifting. This book is not that. So, I brought it back with me to San Francisco in November. Where I finally finished reading it for the first time and promptly read it again. The second time, without long pauses and without other books getting in the way, I could concentrate. It was definitely worth reading. You should read it, too.

In the accounts of the Holocaust that I have read before this book, all of the protagonists have been the people sent to concentration camps, (Primo Levi, Elie Wiesel, Anne Frank) not the people who sent them there, not the people who guarded them there (except for The Reader by Bernard Schlink, about a female guard whose story is simultaneously banal and horrific, read it or see the film). I saw a film a few years ago, called Jojo Rabbit that takes place in Nazi Germany. It’s complicated and layered and funny and tragic. About a young mother who hides a Jewish girl, at great risk to herself and to her young son, a junior member of Hitler Youth. The heroine of that film is a ‘Good German.’ The heroine of Desprairies’ book is not a ‘Good Frenchman.’ The only Good Frenchman is the author who has fashioned a career for herself, by admitting her family’s guilt.

Before I went to Berlin last summer, I had been to Germany only once, and only to Munich. It was a couple years after the Munich Olympics, when PLO terrorists took as hostage and then murdered, 11 Israeli Olympic athletes. And it’s where road signs for the Dachau concentration camp seemed to be everywhere.

Fifty years later, in Berlin, the Nazi past was in full view. But not in an ominous way. The sins of the fathers and grandfathers (and mothers and grandmothers) are acknowledged. There is a Holocaust Memorial and a Jewish Museum. There are tours to nearby Wannsee, where the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was decided. And tours to Sachsenhausen concentration camp (I didn’t go).

I googled “Do Germans atone for their sins through holocaust memorials.” This is the response that AI generated. "While Holocaust memorials (of which there are 2,000) serve as a significant part of Germany's effort to confront its Nazi past and acknowledge the atrocities of the Holocaust, they are considered a key element of a broader "culture of remembrance" which includes extensive education, public discussion, and a commitment to never forget…(M)emorials are important, (but) they are just one piece of a larger process of reckoning with history.”

Paris’ reckoning with its history is different. There are no mea culpas like in Berlin. There is a Museum of Liberation in Paris, which seems more a Museum of Occupation. One document I saw is the official Nazi orders to round up the Jews. Annotated in Marshal Pétain’s own handwriting, the criteria for who is considered Jewish is enlarged. So that more Jews could be rounded up, so that more Jews could be sent to be murdered in concentration camps.

Why was Pétain such an enthusiastic supporter of the deportation of Jews? Here’s my guess - he never got over the humiliation of the Dreyfus Affair. Petain was an officer in the military when an innocent Dreyfus was finally exonerated. Maybe Petain saw deporting as many Jews as he could as his opportunity for revenge. Or maybe because the antisemitism that informed the Dreyfus Affair just never went away, hasn’t gone away.

Drancy is a stop on the RER on the way to Orly Airport. From 1941 to 1944, the French rented buildings to the Germans there. It became the major transit camp for the deportations of Jews from France. Approximately 70,000 prisoners passed through on their way to Auschwitz. Among them, Picasso’s friend, the poet Max Jacob, who had converted to Catholicism many years earlier. Jacob didn’t make it to Auschwitz, frail and sick, he died of pneumonia at Drancy. Beatrice de Camondo, a wealthy Jewess who also converted to Catholicism, was rounded up with her children and Jewish ex-husband and taken to Drancy. The four of them did get to Auschwitz where they were all murdered. A Shoah memorial was created in Drancy in 2012. Which I didn’t know about it until I googled it for this post. (Figs 1, 2, 3)

Figure 1. Drancy as an internment camp

Figure 2. Drancy Shoah Memoriał

Figure 3. Drancy Shoah Memoriał, detail

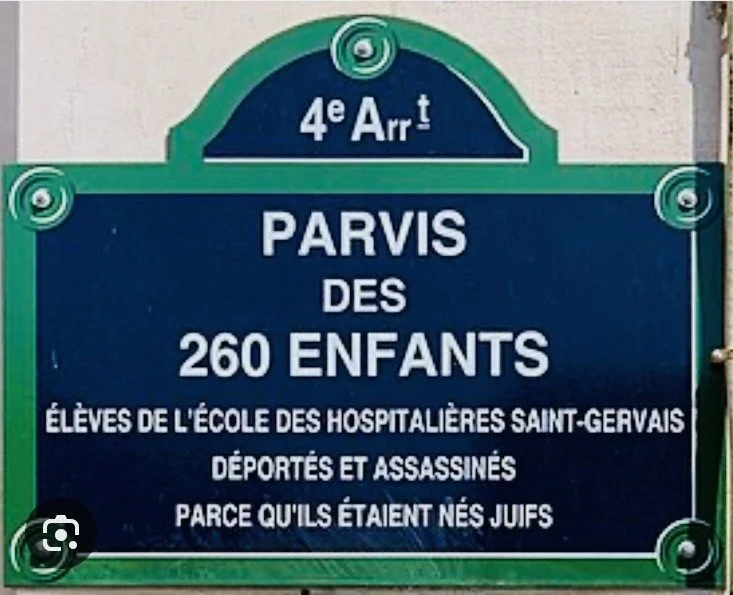

There is a Jewish Museum in Paris (opened in 1998) and a Shoah memorial (opened in 2005). There are plaques on doors, mostly at school with lists of people, mostly children, who attended those schools and were deported to the death camps. (Fig 4)

Figure 4. Plaques on schools, mostly in Marais where there was a large Jewish population

But everything is muted. Anne Frank’s house in Amsterdam is a place of remembrance, Beatrice de Camondo’s house in Paris is a museum of French decorative arts that her father, whose only son died fighting for France in World War I, bequeathed to his adopted country. On the top floor of this elegant house, a film about the family concludes with an acknowledgement of their deportation and death.

The author of The Propagandist is the daughter of a Nazi propagandist. All of her scholarly work could be regarded as a veiled admission of her family’s Nazi past. Finally, with the death of her mother and father and her uncles and aunts, she could tell her family’s story. Although she has done so without her siblings’ blessings.

One reviewer calls the book, “a fist-in-your-face cautionary tale… that covers the genesis, blossoming, demise, and aftermath of …French collaboration during World War II.…” What led me to put the book aside again and again the first time I read it is described by another reviewer as a “mater-of-fact recounting of episodes of casual cruelty to Jews and a generalized antisemitism, as well as venal self-interest.”

To a third reviewer, Desprairies book is a “a cross between the dispassionate inquiry of a historian and a family memoir whose author is searching for catharsis at the end of her attempt to understand her family’s place in the Nazi-collaborationist narrative.”

The author herself has noted that, “This whole story of the occupation and the collaboration in France is so utterly unbelievable that I thought it was absolutely indispensable to base my novel on historical fact. If I hadn’t written my novel basing it on the historical record people would have thought I was off my head.” The book’s translator Natasha Lehrer, commends the book she translated, stating that, “As an insight into the collaboration from the inside, it’s an unbelievably brave book. The fact that so few books of this kind have been written tells you how sensitive this subject remains in France even so long after the war.” Sensitive an hidden.

The narrator/author takes us along as she pieces together what she overheard as a young girl, what she finds in various drawers and closets while her mother is still alive and what she discovers once her mother’s generation of family members has died. Those members include her mother Lucie, who, among other things, worked on a German-sponsored antisemitic art exhibition during the war, her great-uncle Gaston, a newspaper editor, who published German propaganda, her aunt and grandmother who attended at least one party at the German embassy and her great-uncle, Raphaël, who financed his lavish lifestyle by sleeping with wealthy married men, many of whom were Nazis. During the war, he purchased, for a pittance, apartments, furniture and art stolen from Jews sent off to the concentration camps. And there’s more, much more!

We learn about what the author’s mother was doing in the 1940s, when she was in her 20s. The author then picks up threads and follows trails to explain how her mother survived the immediate fall and fallout of the Vichy government and how she successful hid her Nazi past for the rest of her life. Without ever expressing remorse or contrition, without ever changing her world view. In this book, first hand accounts meet professional historical sleuthing.

We read about what might have prompted the author’s mother’s antisemitism. She was a country girl awarded a scholarship to a posh school in Paris. Her classmates teased her about her accent. They were wealthy Parisians, mostly Jewish. Their teasing humiliated her. The Nazis offered the author’s mother an opportunity to turn her humiliation into revenge. Her propaganda was instrumental in sending those same girls to the death camps. Reading this reminded me of the children’s book Strega Nona, the moral of which is that the punishment should fit the crime. Did mocking a country accent really merit a one way trip to Auschwitz? The author’s mother thought so.

Most of the scenes the author recounts from the 1960s take place in the living room of the apartment the author shares with her parents and siblings. The space becomes, after her father leaves for work, what the author calls a gynaeceum, “the women’s quarters in a house in ancient Greece.” By 9:00 a.m., cousins, sisters, some friends and her grandmother, arrive and immediately strip to their underwear and sit around talking. The author calls them, “a tribe of women living in exile from their own country, as if on a desert island.”

Early in the book, the author hears her mother and aunts talking about something her grandmother did in July, 1942, at the Vélodrome d’Hiver. “The Jews were taken there by bus…. It was stiflingly hot. There was an enormous mass of people inside the velodrome and the tumult could be heard through the glass roof. Through a gap in the enclosure a Jewish man had handed my grandmother a gold watch in exchange for a glass of water. My grandmother took the watch but did not bring him the water. It was said with no emotion. I wondered if I had heard right.” Like mother, like daughter.

The Vélodrome d’Hiver was in the 15th arrondissement. It was torn down in the 1950s. When I lived in the nearby 16th, I sometimes walked by a memorial. (Figs 5, 6) I didn’t know what it was for. Unless you know what you are looking for, you don’t know what you are looking at. France wears its Nazi past lightly.

Figure 5. Vélodrome d’Hiver, 1942

Figure 6. Vélodrome d’Hiver Memorial

As one reviewer notes, if this book had ended after the first chapter or if it had continued along in the same vein, “it would have been a charming and slightly comedic slice of French life …. a delightful portrait of (an) eccentric mother and the circle of family females of which she is the center.” But the author doesn’t stop there, she peels back layer after layer of hidden truths, unveiling and revealing more and more about her mother’s life which, without the Nazi stuff is improbable, with the Nazi stuff, is unbelievable, except that it isn’t, the author, a consummate historian, has proof. Her mother’s life was one of flaunting and hiding, figuring out how to make it through the years immediately after the war unscathed and unshorn. And how to live out the long years that followed, which for her, were an anticlimax after all she had accomplished during those heady but all too brief (for her), years from 1940-1944 when she was at the center of what she hoped was the new world order. Thank goodness they weren’t although their lesson seem to have faded from the world’s collective memories.

I know, it’s a somber way to herald in a new year, perhaps we should all just concentrate on the decency that was Jimmy Carter. Gros Bisous, Dr. B.

Thanks to everybody who took time to comment about last week’s post, your comments are much appreciated.

New comment on Betwixt and Between:

Best wishes from Bruno and me to you and Ginevra for a fun- and food- and wine-filled 2025. Martin & Bruno

An excellent post and an inspiration to have a chocolate adventure and possibly cook a bit of pork! Suzanne

Thanku for my first read on day one 2025 Happy New year to you Beverley 🥳💃 So I'm sitting feeling stuffed and kept awake all night by neighbours reveling, feeling like no more Christmas season pud; when suddenly I'm looking up recipes for tarte tatin and shrimp pasta! So I'm off to cook and plan for Parie. Thanku again for artful food and art. Viv

Hi Beverly

Your meals sound wonderful!! I too love seed + mill. It’s in the Chelsea Market walking distance from my house.And I too just finished the Maisie Dobbs series. I loved her books and am sad they’re finished. Ellen

B - are you tricking us? How can you not weigh 200 lbs? I must try all your 'diet' delights. Kathryn

Awesome mantel/fireplace decor….what an incredible daughter ! Still chuckling over the LLB PJ photo….why not send the pose to LLB.? Hand model for Ginevra >>> marvelous….but she should also be doing shampoo commercials with her marvelous natural beauty and magnificent red hair.🧑🦰 Will have to read your essays in segments as so much delightful material! I will have to check out the Maisie Dobbs series with the wartime setting and mysteries. Anxious to read the essay/visit on Mary Cassatt, a most intriguing figure and instrumental in creating an American market for many of the Impressionist. Bill, Ohio

I loved your last Musee Musing. Why don’t you weigh 200 pounds with all of the delicious food you prepare and eat? It all sounded scrumptious. Deedee

A short list of other reviews of this book that you might like to read, either before or after you read the book yourself, which I urge you to do.

Leslie Camhi, The Mordant Intimacy of Cécile Desprairies’s “The Propagandist” https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-mordant-intimacy-of-cecile-desprairiess-thepropagandist

Ori Z Soltes, “The Propagandist” — The Power of Flawed Memory. https://artsfuse.org/298950/book-reviewthepropagandist/

Virginia Reeves, “The Propagandist” https:/www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-reviewpropagandist

Tobias Grey, How a ‘National Family Secret in France’ Inspired Her Novel, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/09/books/cecile-desprairies-the-propagandist.html