Pioneer Women: Brush in Hand, Conquering the World.

Pionnières: Artistes dans le Paris des Années Folles. Musée Luxembourg

I developed a course that I taught for years called Women as Artists / Women as Art. As you might imagine, paintings of women are abundant and mostly by male artists. So teaching that half of the course was very easy. The Woman as Artist part was more difficult to put together. Not as much scholarship in the field. The exhibition I am going to talk about today, Pionnières at the Luxembourg Museum, would have been very helpful. Thematically presented, the exhibition considers the art and lives of female artists who lived and worked during the Années Folles, the Roaring Twenties.

The art of the Roaring Twenties is well known. Museum exhibitions about the decade pop up with some regularity. A few years ago, a fabulous exhibition at the Musée Maillol took as its subject the art and antics of the Japanese artist Foujita. (Figure 1) An exhibition on Man Ray, at the Luxembourg focused on that decade, too. Women were collateral, like Kiki de Montparnasse (who Man Ray shared with Foujita) (Figure 2) and Lee Miller who got tired of being Man Ray’s side kick, so left.

Figure 1. Kiki de Montparnasse, Foujita, 1922

Figure 2. Black and White, Kiki de Montparnasse, May Ray, 1926

But the all male / all the time bias is beginning to crumble. Exhibitions about women artists are becoming less rare. An exhibition at the Luxembourg was called Women Painters 1780-1830 The Birth of a Battle. (Figure 3) The title gives you an idea of where that exhibition was going. Simultaneously, at the Pompidou, there was an enormous exhibition entitled, Women in Abstraction 1860 - 1980. (Figure 4) Which obviously included the decade we’re talking about here.

Figure 3. Women Painters 1780-1830 The Birth of a Battle

Figure 4. Women in Abstraction 1860 - 1980

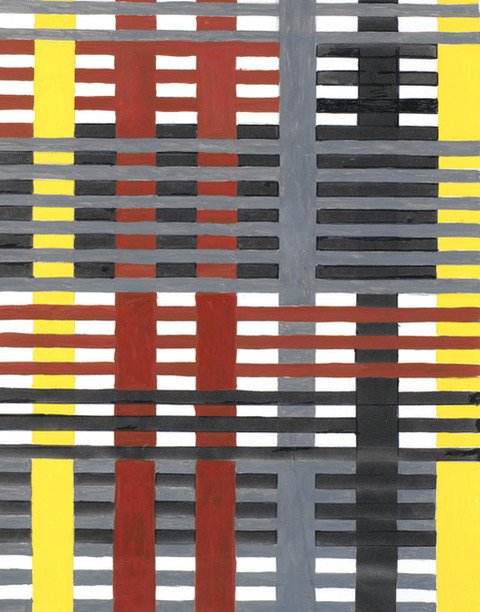

The "Women in Abstraction" exhibition was encyclopedic and exhausting, but it did alert us to the fact that when studying women artists, painting and sculpture are not the only art forms to consider. Of course we know that Picasso created designs for ceramics and costumes for the Ballet Russe, but they were always a side gig for him. Many women didn’t have that luxury. For example, female students at the Bauhaus weren’t allowed to study architecture. That was for their male colleagues. Instead, they took classes in the one department open to them - weaving. So, Anni Albers created textiles of such originality and beauty that the line between art and craft became blurred. (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Study for Unexecuted Wallhanging, Anni Albers, 1926.

If I am honest, which I suppose I should be, this exhibition smacks a little (can a smack be a little? I guess we’ll have to ask Chris Rock) of gender politics. But it’s probably good to know that issues we are wrestling with now, aren’t new. Previous generations confronted them, but probably more discretely. Thank you social media.

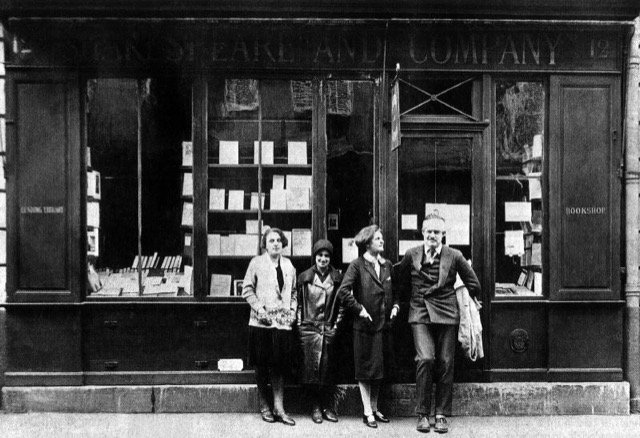

The exhibition’s focus is Paris, specifically the Latin Quarter, Montparnasse and Montmartre. Where bookshops were owned and run by women and art academies were, too. On the bookshop front, the most famous for us, is Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company. (Figure 6) Her French counterpart Adrienne Monnier also had a bookshop, “La Maison des Amis des Livres” also on rue de l’Odeon, just across from Beach’s bookshop. Monnier was first (1915) and it was her encouragement and advice that led Beach to open her own (1919). During the 1920s, the shops became gathering places for French, British and American writers and their readers. Like salon hostesses of previous times and even their own, (Gertrude Stein and Natalie Barney) they hosted soirées for like minded people.

Figure 6. Ernest Hemingway & Sylvia Beach in front of Shakespeare and Company

In the previous exhibition on Women Artists held at the Luxembourg, we learned about the private painting academies run by men where young female students, who were denied entry into the state run academies, could go. I guess it is progress that less than a century later, women were running and teaching in their own private painting academies. Marie Vassilieff founded an art school in 1910 for non French speaking artists. And Marie Laurencin began teaching with Fernando Léger at the “Académie moderne”.

Right after the exhibition’s introduction, we enter a room filled with marionettes and puppets and dolls. (Figure 7) According to Julie Richards, (Sculpture, 2019), during the interwar years, many avant-garde artists sought to eliminate the boundaries between art and life. For women artists, this meant exploring the artistic possibilities of domestic objects that had always been marginalized by male artists and their patrons. As Richards notes, “By virtue of being ordinary, these objects and techniques became potent weapons in women’s struggle to emancipate themselves from the academy and to reintegrate their art into the social world.”

Figure 7. Marionettes for theater performance, Sophie Taeuber-Arp

We are already familiar with marionettes - from paintings of Guignol performances by French artists (Figure 8) to depictions of Punch & Judy shows by English artist. But we don’t imagine that the marionettes or puppets are works of art or that the performances are either. What we consider art are the depictions of those scenes. But at the beginning of the 20th century, Dadaist women artists like Hannah Höch and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, (above, Fig. 7) whose names might be familiar to you, participated in avant garde theater performances by creating marionettes for them. These were serious women artists creating serious art.

Figure 8. Le spectacle ambulant de Polichinelle, Louis-Léopold Boilly, 1832.

And then there was Marie Vassilieff, the Russian emigrée who arrived in Paris in 1907 at age 23, and who, by 1910 had already turned her studio into an academy (as noted above). It was to become a salon, where artists, intellectuals and art critics could gather and when she saw the need, Vassillieff turned it into a canteen, a place to feed fellow artists.

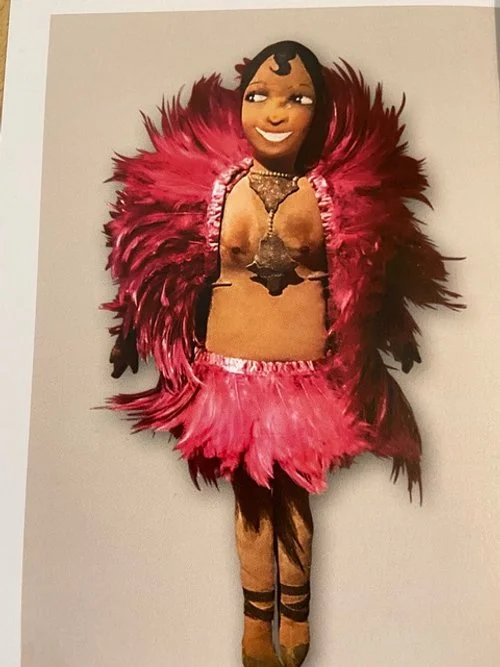

If Vassillieff had one abiding goal, it was to eliminate distinctions - between domestic and public space, between fine arts and applied arts. And somewhere along the way, she invented Portrait Dolls, (Figure 9) inspired by puppet theatre and mask making, the Italian comedia dell’arte and primitivism. Unlike the puppets and marionettes created by Dada artists, her dolls were never intended for live performances. “They were at the intersection of decorative fashion-dolls (and) avant-garde sculptures.” Some were commissioned, others were created to sell on the market, mostly the likenesses of international personalities. (Figure 10) They were shown at exhibitions, often organized by her patron, the French fashion designer, Paul Poiret.

Figure 9. Sigrid Hjertén and Isaac Grünewald, Marie Vassillieff, 1920s

Figure 10. Josephine Baker, Folies Bergère Marie Vassillieff, 1927

As the exhibition reminds us, because women’s art has too often gone unrecognized and undervalued, women have had to develop alternative strategies to survive. They created fabrics and fashions, they designed interiors and objets. Sonia Delaunay, for example, opened a boutique where she sold clothing, furniture and objects she designed. (Figure 11) Her decision to put down her paint brush and pick up a needle and thread was because she lost her income when her properties in Russia were confiscated during the Russian Revolution. And she didn’t want to compete with her husband, Robert. She didn’t paint again until he died.

Figure 11. Coat for Gloria Swanson, Sonia Delaunay, 1923-24

The next room, The Garçonnes sets up the rest of the exhibition. Which is mostly a consideration of the female body. Who owns it. Who defines it. Who decides how it is represented. It is a conversation that didn’t begin 100 years ago. But 100 years later, it is one we are still having. And one we are no closer to resolving.

So, let’s start with a definition. Garçonne, likes Années Folles (Roaring Twenties), has an exact equivalent in English - the Flapper. (Figures 12, 13) Indeed, the Garçonne/Flapper is the poster girl of the Années Folles. She is an emancipated woman, active and autonomous. She goes where she pleases, when she wants. She dances, smokes, participates in sports, drives a car. The Garçonnes are women who ignore conventions. Who own their sexuality by having affairs with men or women, or both. Who sometimes live with partners 'without benefit of marriage’. According to Christine Bard, (Les Garçonnes: Mode et fantasies des Années Folles) the Garçonne did not enter the collective imagination through great literature or avant-garde art but through popular literature and images, (Figure 13) like posters, fashion advertisements and photographs.

Figure 12a Flappers dancing Charleston, New York City, 1926

Figure 13. Garconnes, 1920

Of course one might expect young women to be different after the World and the pandemic. There was a ‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may’ mentality. Life was short and there weren’t enough men to go around anyhow - even if your dream was a husband, 2.5 children and a house in the suburbs (I know that was Friedan and the ‘50s, but really was it that different 30 years earlier - or is it, 70 years later).

Needless to say, not everyone embraced the Garçonne. These women weren’t the equivalent of male actors dressing up as women for a theatrical performance and then putting on their real clothes and going home to their wives, stopping off at their mistress’s place first. No, these were women dressing in a way previously reserved for men. According to Bard, the opponents of women’s emancipation equated it with Garçonnes. Writers contended that the "boyishness" of the flappers’ look and behavior, made them less "marriageable" because they were less “feminine”. Who would want to marry such a creature?

The star of the Garconnes room is Josephine Baker. (Figures 14, 15) She, like other black women and men at the beginning of the 20th century, had come to France seeking the liberty and the dignity they could not find at home. With costumes, photographs and videos, Josephine Baker is described as the ‘New Eve,’ a woman whose muscled body was both elegant and casual. Baker frequented music halls by night and golf courses by day. She opened a cabaret-restaurant, founded a magazine and became one of the highest-paid artists in Europe. And yet the video clips show a young black woman in poses and postures (yes, I know, for which she was famous) that played to the stereotype, that seemed self mocking, that were dehumanizing, that her audiences expected.

Figure 14. Josephine Baker in Banana Skirt, Folies Bergère

Figure 15. Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston, Paris

In the room called “At Home, Unadorned’ we see ‘modern Madonnas’. Women who are tired because having kids is exhausting. While the French government was encouraging women to have more children, to replace all those lost during the Great War and Pandemic, Mela Muter and Maria Blanchard, (Figure 16) both foreign artists living in Paris, showed the real face of motherhood. Their Madonnas were poor foreign laborers and domestic workers, as far away from the 18th century tradition / fantasy of Happy Mothers as you can get. (Figure 17) At the same time, Chana Orloff was taking a different stance. Orloff’s sculptures depict autonomous, independent mothers. (Figure 18) A woman can be both nurturer and provider, a mother and an artist. The painting by Berthe Morisot of Julie with her Nanny is another way of confronting this idea (Figure 19) While Morisot the artist who is not depicted, paints, because that is her job, a woman she has hired, does her job, taking care of Morisot’s daughter.

Figure 16. Famille Tsigane, Mela Muter, 1930

Figure 17. The Visit to the Nursery, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1775

18. Mother and Son, Chana Orloff

Figure 19. Julie with her Nanny, Berthe Morisot, 1884

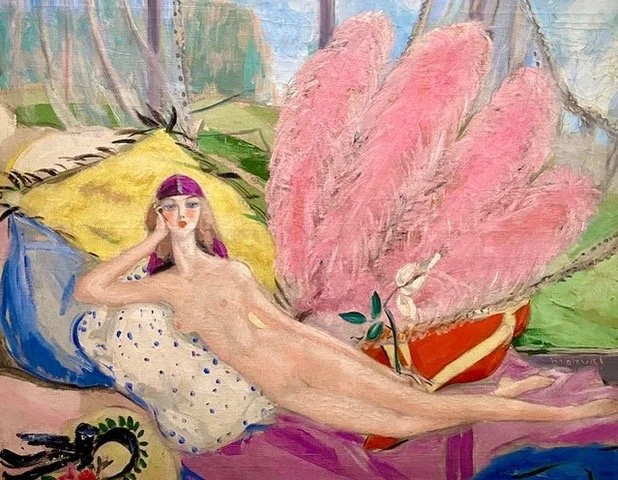

In the rooms that follow, we are shown women exploring themselves, their sexuality. Dressing as they pleased and changing their names as they wished. “Their lives and their bodies, of which they were the first to claim full ownership, were the tools of the trade and the art that they completely reinvented.” It is here that we see the delicate young women of Jacqueline Marval (Figure 20) and Marie Laurencin. (Figure 21) Girls and women whose slender silhouettes compete with the voluptuous models of their male counterparts. And then there is Suzanne Valadon, a former model who mixed naturally and easily with painters and patrons. Her La Chambre Bleue (Figure 22) is a riff on Ingres’ Odalisque (Figure 23), The pose works, but that’s all. Instead of a woman offering herself to the delectation of a male viewer, Valadon’s Odalisque is bulky, with striped pants pulled over her ample thighs and belly. She looks off to the distance, a cigarette in her mouth, books waiting at her feet. She’s not interested in you or what you think.

Figure 20. L’Ètrange Femme, Jacqueline Marval, 1920

Figure 21. Portrait de Mlle Chanel, Marie Laurencin, 1923

Figure 22. La Chambre Bleue, Suzanne Valadon, 1923

Figure 23. Grande Odalisque, JAD Ingres, 1814

In the next two rooms, Portraying the Body Differently and Deux Amies, women continue to take the gaze from the male. The gaze of desire and ownership is replaced by a more complex and nuanced gaze. One that includes desire and sexuality but also worries and constraints. The self-portrait was one way to get it all in, all the different identities - artist, mother, daughter.

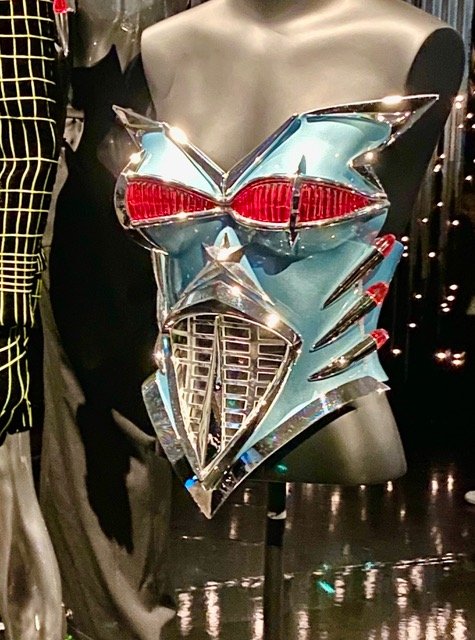

“Deux Amies” is a phrase that refers to a very specific kind of friendship between women. Tamara de Lempicka, a Polish artist is highlighted here. She married twice and had multiple affairs. With both men and women. Her images of women are about the female gaze in general and the desiring gaze of one woman for another woman, in particular. La Belle Rafaela (Figure 24) displays the almost machine like body of one of her lovers. The painting Les Deux Amies depicts two women, limbs intertwined in an erotic moment of intimacy. (Figure 25) But these bodies aren’t soft and pliant, their curves are stylized, generous, not giving. The lesbian singer-icon Suzy Solidor, was another of Lempicka’s models and lovers. (Figure 26) And Lempicka’s self portrait at the wheel of a Bugatti, a car she never owned, is as sleek and stylized as any Art Deco painting. (Figure 27) And reminds me of Thierry Mughler’s automobile series (Figure 28).

Figure 24. La Bella Rafaela, Tamara de Lempicka, 1927

Figure 25. Les Deux Amies, Tamara de Lempicka, 1923

Figure 26. Suzy Solidor, Tamara de Lempicka, 1930

Figure 27. Self portrait in Green Bugatti, Tamara de Lempicka, 1920

Figure 28. Thierry Mugler Automobile Series

The penultimate room, The Third Gender takes us to the doorstep of our present moment. Can people transition from one gender to another. Do they have to choose. Is there a “third gender”. We are told that in a few cosmopolitan capitals, gender was a fluid concept. Where cross-dressing and trans-gendering just happened. I wonder where that was. The Danish artist Gerda Wegener, (Figure 29) for example, married her husband when he was a man and stayed with him after he began identifying and dressing as a woman. Her story is not unique, of course. When the Mt. Everest climbing travel writer James Morris became a woman, she continued to live with her wife, with whom she had fathered five children. When Gerda’s husband decided to have a sex realignment operation, their marriage was annulled because same sex couples couldn’t marry in Denmark. When her husband died of complications from the surgery, Gerda was left an unmarried widow.

Figure 29. Deux cocottes avec des chapeaux, Gerda Wegener, 1920

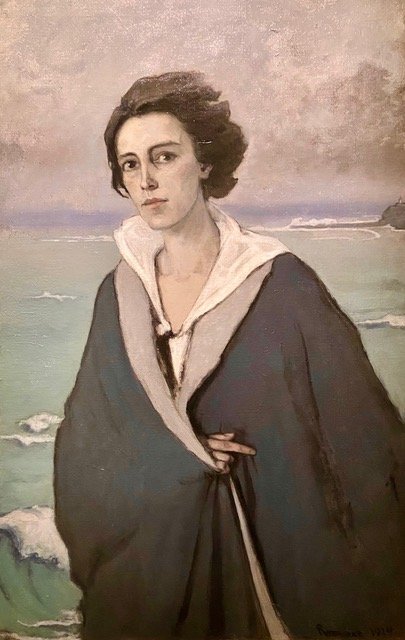

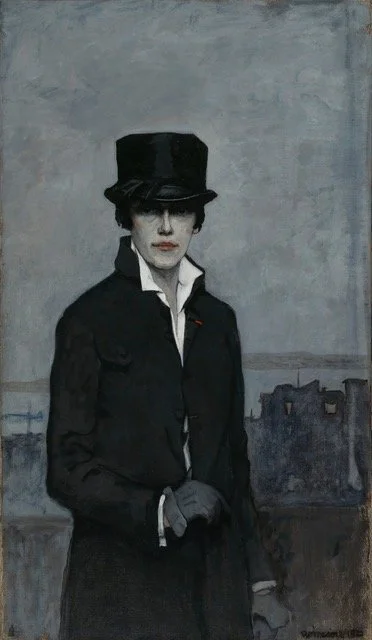

Romaine Brooks, the wealthy American portraitist who made Paris her home, is also represented in this section. She has been described by Whitney Chadwick (Women, Art, and Society) as the first female painter to consciously forge a new visual imagery for the 20th century lesbian. Her self-portraits are repudiations of standard representations of femininity. (Figure 30) Sticking to a palette of black and grays, she presents herself as strong and resolute, a modern lesbian whose preferred dress was the “less gendered-bound clothing of equestrians.” (Figure 31)

Figure 30. Au bord de la mer, Romaine Brooks, 1912

Figure 31. Self Portrait, Romaine Brooks, 1923

The final room in the exhibition is called Diversity. (Figure 32) As the exhibition notes remind us, since these women artists were already on the fringes of the art world, they had nothing to lose by being open to new cultures, and so they were.

Figure 32. La Famille, Tarsila do Amaral, 1925

This is an exhibition with a point of view. It may not be yours but it is well presented and well documented. It’s worth checking out.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.