Art as Decoration: Impressionist Style

Impressionist Decorations: Tracing the Roots of Monet’s Waterlilies: Musée de l’Orangerie

A few years ago, I saw an exhibition at the Musée de l’Orangerie, called Les Nabis et le décor. (Figure 1) The Nabis was a group of young French artists who had gone to art school together and then worked and exhibited together in Paris from 1888 until 1900. They have been celebrated as the link between Impressionism and Abstraction. One of their goals was to break down the barrier between fine art and decorative art. In 1890, when he was 19, Maurice Denis reminded his fellow Nabis that “… a picture, before being a battle horse, a female nude or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order." It was a lesson the Impressionists had already learned.

Figure 1. Les Nabis et le décor, exhibition poster, Musée de l’Orangerie

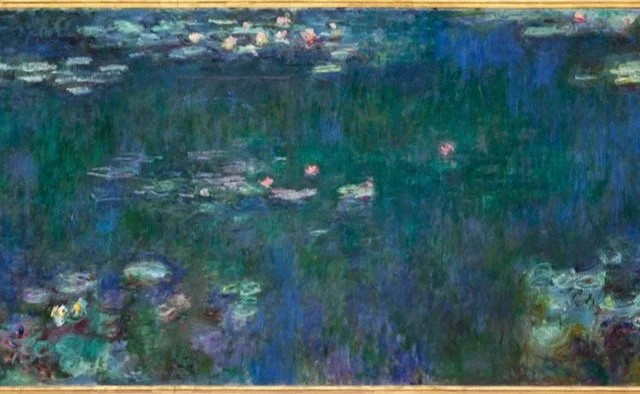

The current exhibition at the Musée de l’Orangerie, ‘Le décor impressionist aux sources des nymphéas, (Impressionist Decorations: Tracing the Roots of Monet’s Waterlilies) (Figure 2) has the same theme as the exhibition on the Nabis. About time, right? Since one of the largest decorative ensembles that can be viewed in its entirety, in one place, is a permanent fixture of the Musée de l’Orangerie, Monet’s Nymphéas. A gift from the artist to his countrymen to mark the end of the Great War. (Figure 3)

Figure 2. Me with the Waterlilies at the Orangerie

Figure 3. Detail of Waterlilies, Claude Monet, Musée de l’Orangerie

It is surprising that it has taken so long for an exhibition on Impressionist decoration to appear. One might have thought that everything there is to say about the impressionists has already been said. And yet this exhibition proves otherwise. It presents paintings that were created as part of a series or cycle, which have mostly been separated from their mates, sold as individual canvases, their contexts lost. They are here reunited, their contexts reestablished. Quotes by Impressionist artists are scattered around the exhibition. Like this one which Degas said to the art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, “It has been my lifelong dream to paint walls.” And Renoir to somebody else, paintings were made to “brighten the walls.” Monet, and this won’t surprise you, considered his Waterlilies ‘great decorations’. Of course, while these artists were insisting that they wanted to decorate walls, critics were calling their paintings ‘no more than wallpaper.’ Baudelaire dismissed their paintings of flowers as “dining-room paintings.” And that’s a bad thing?

This exhibition, like the one on the Nabis, is a glorious feast for the eyes. Even for those of you who think you know everything about Impressionism.… there are some beautiful surprises here. But I will admit, it gets off to a slow start.

The first image is a huge Circus Clown painted by Renoir. (Figure 4) Which, because we know Renoir’s later works, is rather shocking. It was commissioned by the owner of the café of Cirque d’Hiver, the winter circus in Paris. This is John Price, a famous clown who, with his brother William, performed as ‘clown-musiciens’. As a private commission for a particular space, this painting ticks both boxes. But it isn’t delightful, it isn’t especially decorative either, even if the clown’s costume is. His expression is stern and the audience is silent. It seems a peculiar moment to choose for a place that is supposed to be gay and a person who is supposed to be entertaining. Let’s blame it on age. Renoir was 27 when he painted it. The exhibition includes a few other examples like this, odd and a little somber. Which you can discover on your own.

Figure 4. Clown Musical, Pierre Renoir, 1868

But I will tell you about another surprise, frescoes painted by Paul Cézanne in 1860, on the walls of a drawing room in the grand property his father, the wealthy banker, had purchased a year earlier. (Figure 5) They are not paintings you would associate with Cézanne. And they are not paintings you would look at if Cézanne hadn’t painted them. The theme is a traditional one, the Seasons, on four panels, each with an allegorical figure. Spring is a statuesque young maiden holding a length of blossoms. Summer is sort of seated, surrounded by the bounty of the harvest.

Figure 5. Les Quatres Saisons (Spring, Summer, left; Fall, Winter, right) Paul Cézanne, 1860-61

There is another fresco which Cézanne painted in this drawing room. Nine years later and light years apart. After art school. It is the only one of these paintings that I recognized. Christ in Limbo. (Figure 6) How Cézanne has changed! The exhibition includes a video that imaginatively reconstructs how the frescoes were displayed and how they were removed from the walls when the property was sold in 1899. Even when he lived in Paris, Cézanne spent a lot of time here, in the garden, painting views of his muse, Mont Sainte Victoire. (Figure 7)

Figure 6. Christ in Limbo, Paul Cézanne, 1869

Figure 7. Mont Sainte Victoire, Paul Cézanne, 1895

There’s a painting by Renoir that is given pride of place in another room. It is not a fresco but it evokes fresco painting. (Figure 8) Which Renoir may have experimented with when he was in Italy in the early 1880s. This painting is one I have known forever. Since it lives at one of my favorite college student haunts, the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It doesn’t travel much. It hasn’t been in France since 1922. It is called Grandes Baigneuses and was painted from 1884-1887. Of the three figures in the foreground, the one looking toward us is the beautiful model Renoir would marry and on the right splashing her companions, is Suzanne Valadon, the model who became a painter. Although not created for a particular space or client, for Renoir it was decorative because it was inspired by artists of the past who, like him, were easel painters. It has always seemed like a painting from a different era to me and now I understand, that was what Renoir was going for. And he succeeded beautifully. Another painting, Male Nude or River God, (Figure 9) was also not commissioned. The figure is as beautiful as any of Renoir’s female nudes, maybe a little too pretty.

Figure 8. Les Grandes Baigneuses, Pierre Renoir, 1884-87

Figure 9. Le Fleuve (River God) Pierre Renoir, 1885

Let’s go back to the Seasons. Cézanne was not the only Impressionist to paint them, of course. Édouard Manet did too. And like Cézanne, his Seasons are female figures. But that’s where the similarity ends. Cezanne’s seasons follow the classical traditional formalized and illustrated in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia. (Figure 10) Young women holding appropriate attributes and wearing classical robes.

Figure 10. Abundance, Cesera Ripa, 1608

That’s not the direction Manet took when his friend, Antonin Proust (no relation to Marcel) commissioned him to paint the Seasons. Only two of the intended four panels were finished before Manet died in 1883, at 51, of complications from syphilis. Rather than classically clad maidens holding attributes. Manet paints the actress Jeanne Demarsy as Spring (Figure 11) in profile, in front of a verdant tree and blue sky, wearing a pale flowered dress and bonnet, and holding a lacy parasol. Dressed in brown, and also in profile, the demi-mondaine Méry Laurent, is Autumn. (Figure 12). We know that actresses and ballerinas were mostly young working women whose reputations were often unfairly maligned. Demimondaines were (are) something else, ‘kept’ women, courtesans. ‘Kept’ by wealthy men for whom they represent a respite from the ‘real’ world of wives and families and responsibilities.

Figure 11. Jeanne Demarsy Le Printemps, Édouard Manet, 1881

Figure 12. Méry Laurent, l’Automne, Édouard Manet, 1882

The attire of these women remind me of portraits painted by the 18th century American artist, John Singleton Copley. He color coded his women based on age. Young women were in the springtime of their lives, wear pastels. (Figure 13) Mature women, in the Autumn of their years are stout and wear greens and browns. (Figure 14) Old women, in widow’s weeds, are shrunken and frail. (Figure 15) The seasons of life.

Figure 13. Mrs. Daniel Sargentm Springtime, John Singleton Copley 1763

Figure 14. Mrs. Exekiel Goldthwait, Autumn, John Singleton Copley, 1771

Figure 15. Anna Dummer Powell, Winter, John Singleton Copley, 1764

Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet also painted the Seasons. But differently. The allegorical figures are gone. Their paintings celebrate the countryside at different times of the year. You might think back to the calendar pages of the Très Riches Heures du Duc du Berry from the early 1400s which depicts the labors of the peasants and the pastimes of the nobility against a backdrop of changing seasons. (Figs 16, 17)

Figure 16. Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, April

Figure 17. Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, February

Camille Pissarro received a commission from the Parisian collector, Achille Arosa for four overdoor panels. Pissarro began painting in 1872 when he was living in Louveciennes, just outside of Paris. That first panel, Winter, is rooftops in the snow. (Figure 18) The other three panels painted the following year, depict the countryside around Pontoise, Pissarro’s new home. (Figure 19) According to art historian and Pissarro’s great grandson, Joachim Pissarro, these painting were an "attack on … the French academic system of painting.” The artist took one of the most common allegories in Western art and got rid of all the allegory. “None of the traditional symbols …(are here), no grape harvest or wine making scenes for autumn, for example.” Because, no matter the season, “field workers, in the rural world, carry on business as usual” And that’s what Pissarro was going for, that’s what we have here.

Figure 18. The Four Seasons, Winter, Camille Pissarro, 1872

Figure 19. The Four Seasons, Summer, Camille Pissarro, 1873

Monet’s four paintings are perhaps the Four Seasons, but they definitely depict the location for which they were painted. A newly purchased home owned by Monet’s patron, Ernest Hoschedé, the department store magnate, art collector and critic. The paintings include The Hunt (Figure 20) and Turkeys (Figure 21), which is always labeled, ‘unfinished decoration’ because Hoschedé went bankrupt before it was completed. Monet’s history with this patron and his family was complicated and ended (or began) after the death of both Monet’s wife and his patron and Monet’s marriage to Alice, Ernest Hoschedé’s widow, who had probably been Monet's mistress for years.

Figure 20. La Chasse, Claude Monet, 1876

Figure 21. Les Dindons. (Turkeys) Décoration non terminée, Claude Monet, 1877

Les Dindons, is one of my all time favorite paintings. Maybe because Benjamin Franklin proposed that the turkey rather than the Bald Eagle should be the emblem of the United States since the turkey was native to North America. Maybe it is because of Giovanni de Bologna’s sculpture of a turkey at the Bargello that I visit every time I’m in Florence. (Figure 22) Maybe it is because depictions of American as one of the four corners of the world often include turkeys. But no other turkey is as outrageously fabulous as Monet’s unfinished painting of Turkeys. The white and pink/reds of their bodies sprinkled across the green lawn read as pure decoration. Not until your eye becomes accustomed to all that beauty, do you realize that these are turkeys scattered over the field in front of the home for which is was painted.

Figure 22. Tacchino (Turkey), Giambologna, 1567

What else should I tell you about? There are fans by Degas and Pissarro, the former with ballerinas, the latter with peasants/farmers (Figure 23). There are paintings and drawings on cement and ceramics. And plates designed by Marie Bracquemond and her husband (Figure 24). Berthe Morisot is here (Figure 25) and so is Mary Cassatt (Figure 26), the only impressionists who won a large scale, public commission. But it was ephemeral and it was in Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. There is a triptych by Gustave Caillbotte, of fishermen and bathers and boatsmen along the River Yerres. (Figure 27) Painted when Caillbotte was living in his family home, near the house Monet was decorating for Ernest Herschodé. Painted in the hopes of getting a commission to decorate somebody’s home, too.

Figure 23. Farmer Fan, Pissaro top; Ballerina Fan, Degas, bottom

Figure 24. Plate, Haviland. 1890s

Figure 25. Bergère couchée, Berthe Morisot, 1891

Figure 26. Preparatory drawing, Women’s Building, WCE, Chicago, Mary Cassatt, 1891.

Figure 27. Decorative Panels, Gustave Caillebotte, 1878

But now I want to show you the final rooms of the exhibition, the grande finale. Exquisite and exquisitely decorative paintings of gardens and flowers by Caillebotte and Monet. Seriously, if you see nothing else in this exhibition, before making your way to the Water Lilies, you must come to see these fabulous rooms of pure beauty.

We’ll begin with Monet. About the time Monet and his family moved to Giverny, he received a commission from his art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel to paint 40 canvases, of which 36 survive, to be hung on six double doors in the drawing-room of his home. Two of those doors has been recreated here. It is gorgeous and luscious. Ripe fruits and perfect blooms. (Figs 28, 29) As we know, Monet was as much a gardener as a painter. His passion for flowers is legendary. He painted them in the garden, he painted them in bouquets, in baskets, in vases. (Figure 30) Anywhere and everywhere. He once said, "I perhaps owe it to flowers for having become a painter" and also, "What I need most of all are flowers, always, always”

Figure 28. Door Panel, Claude Monet

Figure 29. Panel detail, Claude Monet, 1882

Figure 30. Chrysanthèmes, Claude Monet, 1897

The same was true for Gustave Caillebotte, a lifelong gardener. Familiar with the door panels Monet painted for Durand-Ruel, he set out to create something comparable for his own house at Petit-Gennevilliers near Paris. Caillebotte made two dining-room doors into a painted greenhouse with orchids in the upper panels and other blooms in the lower panels. (Figures 31, 32) There are other fabulous paintings and panel by Caillebotte here, too. I’ll stop with one of each, a panting of chrysanthemums. And a blanket of daisies. (Figures 33. 34)

Figure 31, Door Panels, Gustave Caillebotte, 1893

Figure 32. Door Panels, Gustave Caillebotte, 1893

Figure 33. Chrysanthème, Gustave Caillebotte, 1893

Figure 34. Daisies, Gustave Caillebotte, 1892-93.

I hope you can come to see this exhibition. It will do you a world of good.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.