A Jack of all Trades and a Master ….. of them all!

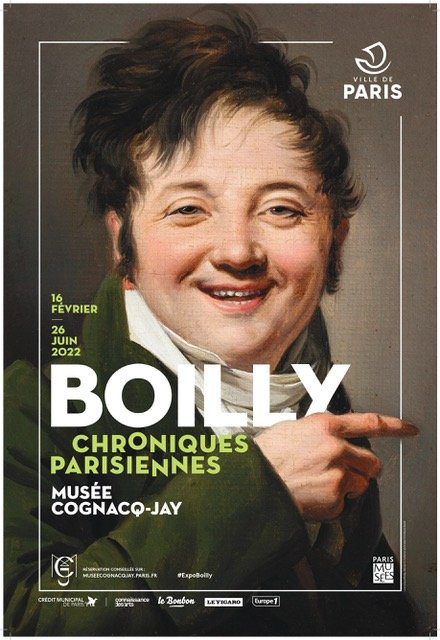

Boilly Chroniques Parisiennes

I am a huge fan of the temporary exhibitions at the Musee Cognacq-Jay. A jewel box of a museum in the Marais whose permanent collection is mostly 18th century French paintings, sculptures and objets collected by the couple who founded La Samaritaine. Somehow the temporary exhibitions always seem to be perfect for the space. And there is always a delightful ‘show-stopping’ surprise. With the exhibition about the Marchands Merciers it was a full size recreation of Watteau’s L’Enseigne de Gersaint. (Figures 1 & 2)) More recently with L’Empire des Sens, it was a little room with naughty pictures. (Figure 3) This exhibition includes naughty images, too. In that same room.

Figure 1. L'Enseigne de Gersaint, Watteau painting

Figure 2. L'Enseigne de Gersaint, Watteau, full scale recreation, Musée Cognacq-Jay

Figure 3. Little room at Musée Cognacq-Jay to look at naughty pictures

The title of the exhibition under review this week is suspiciously similar to the exhibition reviewed last week. We have tumbled onto another chronicler of Paris. Last week’s chronicler lived at a moment of great upheaval. Marcel Proust’s short (51 years) life began at the beginning of the Belle Époque and ended at the beginning of the Années Folles (the Roaring Twenties, 1871 - 1922). His chronicle is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest book ever written.

The Parisian chronicler whose work we will discuss this week, Louis-Leopold Boilly also lived during turbulent times in French history (are there times that aren’t turbulent? I am beginning to doubt it). And this time, for somebody who mostly looks at pictures, I am feeling on firmer ground since this chronicler was a painter. Born in 1761, the beginning of his professional life coincided with the French Revolution and got complicated quickly when a fellow artist denounced him. During the years that followed, the artist experimented and triumphed. He was always ready to try new ways of telling his stories and new ways of earning his livelihood. He could be listed in the Guinness Book of World Records for the most different styles of painting.

Proust’s Paris was inhabited by the beau monde. People whose wealth (whether inherited or earned) permitted them the luxury of time. Beautifully coiffed and attired, their activities centered around elegant soirées at restaurants and theaters or at intimate salons. (Figure 4) Proust was a social climber and a dandy who used his friendships to gain access to the rarefied world of the leisured class.

Figure 4. Une soirée au Pré Catalan, Henri Alexandre Gervex, 1909

Boilly’s Paris was very different and not only because he lived a century earlier. He was a working man supporting a growing family. He identified with people trying to get by, who took their leisure where they could find it, at impromptu entertainments in the street (Figure 5) and in the parks. And people who by necessity attended to more serious occupations, like waiting for the mail and appearing for the draft. Proust schemed his way into society, Boilly schemed his way into profitable enterprises.

Figure 5. Carnivale, Louis-Léopold Boilly, 1832

As I walked through the exhibition, I kept thinking that I was at an exhibition of 18th and 19th century French, English and American painters. There were amorous scenes in the style of Fragonard and Boucher. And Tetes d’Expression like those by Charles Le Brun. And then caricatures like Daumier. There were crowded city scenes that reminded me of Hogarth and portraits that reminded of the Philadelphia artist, Charles Willson Peale. In another room were trompe l’oeil paintings like those by Peale’s sons Raphael and Rubens. Elsewhere, I was reminded of artists like Vermeer who experimented with the camera obscura and other optical devices. Whew.

But of course this isn’t an exhibition of works by all of those artists. This is an exhibition of paintings by one artist. A hard working and talented artist. An artist whose work is so varied and so good that I really must introduce him to you.

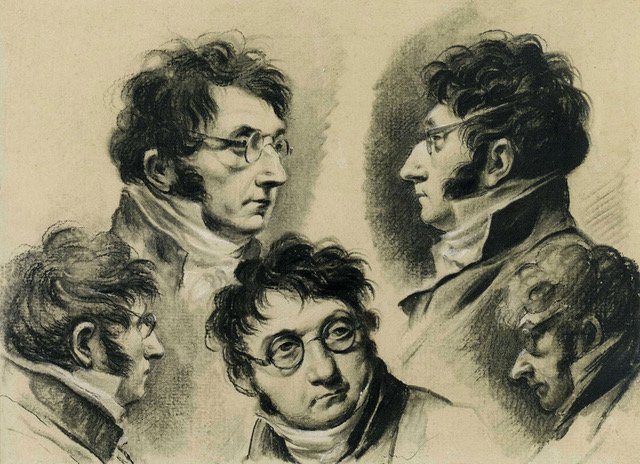

Louis-Léopold Boilly was born in 1761 in northern France, near Lille, the son of a wood carver. He was mostly self taught, although he spent some time with a master of trompe l’oeil paintings in nearby Arras before abandoning the provinces and moving to Paris, where he was living by 1787. (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Sheet of Self Portraits, L-L Boilly, 1810

Between 1789 and 1791, Boilly executed eight small canvases for an Avignon collector, Esprit Calvet. That commission and other paintings by Boilly of the time are usually erotic, sometimes amorous and when in pairs, more often than not, moralizing. (Figures 7, 8) Ah, the price of passion.

Figure 7. La Résistance inutile, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1770-1773

Figure 8. Amorous Couple (could easily have the same title as above) Boilly,

In addition to these standard topoi, Boilly or his patrons hankered after women displaying their Sapphic tendencies. So we are treated to Two Young Women Kissing (Figure 9), Women measuring their feet (what’s that a euphemism for?) (Figure 10) and Indiscrète, (Figure 11). These are the paintings on view at the Cognacq-Jay in the ‘viewers advised’ room on the second floor. Obviously we aren’t talking about scenes like the ones we saw (or averted our eyes from) between Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan in the film Ammonite, (on the life and work of a female paleontologist) (Figures 12, 13) but still. Indiscrète, is especially charming as two young women try to keep an unwanted man from intruding upon their private pleasures. Another painting from the period by Boilly that I found, but isn’t in this exhibition is called, ‘La toilette intime’. (Figure 14) The subject is female personal hygiene. It depicts a young woman seated on, or more accurately, straddling a bidet. Did you know that the word bidet means pony and bider means to trot. The idea is that to use a bidet, one has to straddle it, much as one straddles a pony to ride it.

Figure 9. Two Women Kissing, Boilly

Figure 10. Comparing Little Feet, Boilly

Figure 11. Indiscrète, Boilly

Figure 12. Kate Winslet & Saoirse Ronan, Ammonite

Figure 13. Two Young Women Kissing, Boilly, detail

Figure 14. La toilette intime, Boilly

Anyhow, it was pictures like these that got Boilly into trouble in Revolutionary France. Controlled by a group of men who apparently had no time for sex and less time for humor. Boilly was denounced by a fellow artist and condemned by the Comité du Salut Public in 1794. This was at the height of the Terror. He was condemned for painting subjects 'of an obscenity repugnant to Republican morals'.

When members of the Comité came to Boilly’s studio to investigate (if they did, sources vary), they were greeted with a tableau entitled, ‘Marat Triumphant’. (Figure 15) Since the revolution had pretty much killed the market for naughty boudoir scenes, Boilly had begun exploring alternative subjects. The painting in his studio was not one he had begun in haste to prove his Revolutionary bona fides. He had been painting it for a competition that had been announced by the Revolutionary government to commemorate the one year anniversary of Marat’s acquittal.

Figure 15. Marat Triumphant, Boilly 1794

Here’s the story. In April 1793, Marat was arrested on charges that he was using his newspaper to destroy the National Convention. He was tried before the Revolutionary Tribunal where he spoke passionately in his own defense explaining that he was not a guilty man "but the apostle and martyr of liberty". He was immediately acquitted. The crowd hoisted Marat onto a table decorated with palms and wreaths. The enemy of the revolution became one of its most important leaders, both to the members of the Convention and to the people on the streets of Paris.

‘Marat triumphant’ was the most ambitious work Boilly had painted up to that date. Many more multi-figural compositions would follow. In all of them, the real subject is not what is taking place in the center of the canvas but what is taking place in the crowds of people who gather around to see what is going on, to participate in what is going on. Spoiler alert: The figure with the red bonnet in front of Marat is probably a self-portrait. Like Alfred Hitchcock, Boilly always makes a cameo appearance.

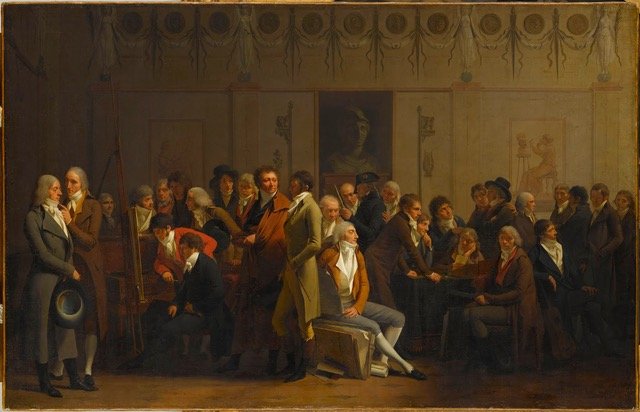

As events would have it, Boilly never finished this painting. It wasn’t prudent after the fall of Robespierre. But he entered another public competition a few years later. His multi-figural painting of 1798, which wisely avoided political content, is titled, Artists in Isabey’s studio (Figure 16) Boilly is here, dressed in red like the artist whose studio is depicted. Isabey leans toward an easel, Boilly stands nearby. Almost all of the figures in the scene are identifiable. It is a painting in the tradition of Zoffany’s Royal Academy of England, (Figure 17) painted twenty years earlier. Yes, there were female members of the Royal Academy, no they were not at this meeting but their heads were hanging on the walls. It has been noted that Jacques Louis David is not in Boilly’s painting, he was too important by then. But nobody mentions that female artists of the time aren’t here, either.

Figure 16. Artists in Isabey’s Studio, Boilly, 1798

Figure 17. Members of the Royal Academy of England,Zoffany, 1778

From actual events and identifiable people to genre scenes like this one which show that Boilly wasn’t quite as far from his naughty pictures as all that. (Figure 18) The scene is the courtyard of a prison for women, the former Convent of the Madelonnettes, originally founded to help former prostitutes and "victims of seduction’. BTW we still punish the victim of aggressions rather than the perpetrators. By the mid 1790s, the Convent had been transformed into a prison for female criminals and girls whose parents had sent them there, to curb their ‘passionate natures’. But if you look at the easy interaction between the soldier / guards and the women detainees, I would be surprised if any passions were curbed.

Figure 18. Prison of the Madelonnettes, Boilly

Here’s another, The Arrival of a Stagecoach in the Cour des Messageries from 1803. (Figure 19) The Messageries was a stagecoach company that transported post and people. Boilly depicts the north facade of the Cour des Messageries, exactly as it looked. While workers take sacks off the carriage, one couple flirts on the left, while a soldier presses his attentions upon a young woman to the right. At the center, a family, Boilly’s own, (Figure 20) embraces. Familial accord is confirmed by the family of chickens in the foreground.

Figure 19. The Arrival of a Stagecoach in the Cour des Messageries, Boilly

Figure 20. The Arrival of a Stagecoach in the Cour des Messageries, detail, Boilly

Boilly stayed away from current events as a subject for 15 years, but in 1808, he jumped in again and painted Le départ des conscrits. (Figure 21) Maybe Boilly had a son of conscription age. While his contemporaries’ canvases celebrated the grand deeds of great men, Boilly depicted the repercussions of the decisions made by those grand men on the middle and working class people whose lives were turned upside down by them. The imperial armies depended on conscription. And as battlefronts multiplied and fatalities mounted, the need for conscripts rose.

Figure 21. Departure of the Conscripts, Boilly 1807

Boilly’s painting shows a crowd of conscripts in front of the Porte Saint-Denis. As these conscripts bid their emotional farewells to their loved ones nobody knew what lay ahead - the Battle of Eylau, (Figure 22) one of the bloodiest battles of the Napoleonic Wars. The scene is not one that elicits much confidence. The soldiers are disheveled, the scene is disorderly. Boilly is here to bear witness. He is just left of center, next to the standard bearer.

Figure 22. Napoleon at the Battle of Ellau, Baron Gros

Some years earlier Boilly, the artist/entrepreneur had found a steady source of income. Small format bust portraits! Which the artist advertised he would complete during a “session of less than two hours”. A sitter arrived at the artist’s studio and assumed a pose as directed. Two hours later, with no preparatory sketches needed, the portrait was finished. Five thousand faces of the new bourgeoisie were thus immortalized by Boilly's brush. Nearly a thousand of those portraits survive. Of them, 40 are on exhibition here. (Figure 23) We’ve come a long way from Hyacinthe Rigaud. (Figure 24) Portraits are no longer the privilege of rank and wealth.

Figure 23. Portraits, Boilly

Figure 24. Louis XIV, Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701

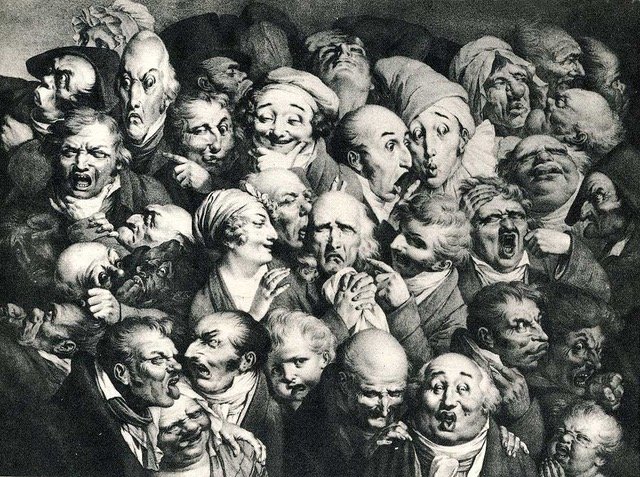

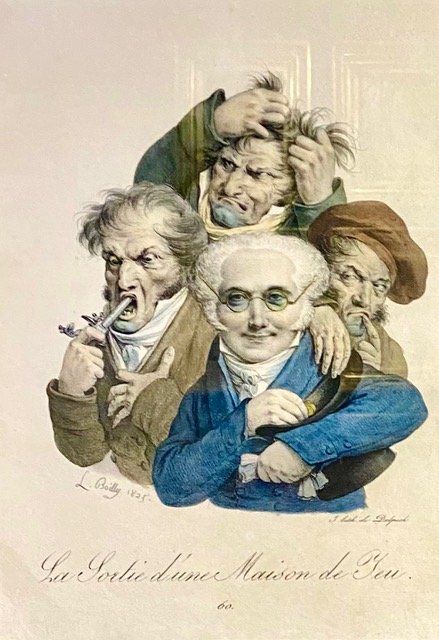

Looking at all those faces, caricature seems an obvious next step. And the artist took it. (Figures 25, 26) Inventories of expressions and passions, individual and archetypical. What a relief it must have been after all those serious sitters! And then it gets a little less playful. There are the Vices and the physiognomies of the various professions. (Figures 27, 28)

Figure 25. Thirty Five Expressive Heads, Boilly

Figure 26. Les Grimaces, Boilly

Figure 27. The Dentist, Boilly

Figure 28. La Sortie d’une Maison de Jeu, Boilly

But wait, there’s more. Boilly triumphed with trompe l’oeil. Did you know that he coined that phrase? He was truly a master of the form. One painting shows various drawings, sketches and etchings on a wooden frame, under a broken glass. But the wood isn’t real and you won’t get cut if you touch the painted broken glass. (Figure 29)

Figure 29. Trompe l’oeil, Boilly

Boilly’s Cluster of White Grapes (Figure 30) shows us that while this artist may have been self taught, he wasn’t unlearned. This trompe l’oeil refers to the legendary Zeuxis, the first Greek painter who is said to have duplicated nature so perfectly that birds pecked at the bunch of grapes he painted. Most fun of all is that Boilly signed his paintings on scraps of paper. Painted scraps of paper. (Figures 31, 32) Trompe l’oiel squared

Figure 30. Cluster of Grapes, Boilly

Figure 31. Tromp l’oeil Crucifixion, Boilly

Figure 32. Tromp l’oeil Crucifix, detail, Boilly

Boilly was fascinated by scientific and technical inventions. He collected optical instruments like the zograscope (Figures 33, 33a) which magnified flat pictures and enhanced a picture’s sense of depth. He happily learned lithography and photography, too. There is an openness and willingness to learn and experiment that seems exactly right for an artist who presents himself to the world with such a jolly expression. He’s having fun, we should, too. (34)

Figure 33. L’Optique, Boilly

Figure 33a .Optique, Boilly & Zograscope

Figure 34. Surprise ! Self Portrait, Boilly

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.