Parsing the Passions

Le Théâtre des émotions (Musée Marmottan-Monet & Héroïnes Romantiques (Musée de la Vie Romantique)

In the waning days of May before I left for the heat of the Côte d’Azur, I saw two exhibitions. Both focused on the passions and how they were portrayed, mostly in paintings. I spoke about this subject a little while ago, in reference to, who else: Proust.

The first exhibition I saw, at the Musée Marmottan Monet, is called Le Théâtre des émotions (The Theatre of Emotions). The second, at the Musée de la Vie Romantique is Héroïnes Romantiques (Romantic Heroines) The first includes paintings and sculptures from the 14th through the 21st centuries, from the middle ages to now, well last year. Encyclopedic in focus, if encyclopedic can actually be a focus. The second exhibition concentrates on depictions of historical and fictional women in 19th century paintings, literature and the performing arts. Both exhibitions are here for a while, at museums slightly off the beaten tourist path. Try to see at least one of them if you’re in Paris this summer and then discover a new neighborhood.

Getting back to Proust (can you tell I am having a hard time staying away from him?) I had been surprised to read his reaction to the Personifications of the Virtues and Vices, in that jewel box of a space, the Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel in Padua, painted from 1304-1306 by the Proto-Renaissance Italian artist, Giotto. In one passage of À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time), Proust wrote about a servant girl he saw one year at Cambray. She was so near giving birth that she looked like Giotto’s figure of Caritas from the Arena Chapel. (Figure 1) So square and matronly was she. Proust mused that Giotto's personifications display none of the virtues or vices they personify. I wanted to take him aside and say, but surely Monsieur, you know that personifications require attributes. Period. For Charity it is the basket of plenty that she holds and shares. For Justice, it is the sword and scales she holds and sometimes the blindfold she wears, all signifying that Justice is swift (sword), impartial (scales) and fair (blindfold). (Figure 2) For America, one of the four corners of the world, it is the bow and arrow she holds, the headdress she wears, the alligator behind her and the severed head between her legs. (Figure 3)

Figure 1. Caritas (Charity), Giotto, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1304-06

Figure 2. Justice, Cesara Ripa

Figure 3. America, Ripa

The attributes held by the personifications in the Arena Chapel weren’t Giotto’s personal pictorial language. They were already well known when he was working. However there was no guidebook for Giotto to consult. The attributes of of (mostly) abstract ideas, weren’t codified until the 16th century by Cesare Ripa when he published his compendium entitled Iconologia. There are earlier editions, but the first illustrated one was published in 1593.

Figure 4. Mary Magdalene

One of the first paintings in this exhibition is called ‘Mary Magdalene in Tears’ from 1525 (Figure 4). How do we know that this woman is the Magdalen? Because she holds the pot of oil with which she anointed Christ's feet. She isn’t really in tears. She is just holding a handkerchief. And a woman holding a handkerchief symbolizes sadness because one uses a handkerchief to wipe away one’s tears.

Dürer’s Melancholia I, from 1514, (Figure 5) is also here. She is winged, crowned and gowned. But she seems discouraged, maybe disgruntled, sitting with her head on her hand. She holds a calipers but doesn’t seem interested in it or any of the other tools scattered around her. The Greeks believed that the human body was composed of four Humors. Sanguine, Phlegmatic, Choleric and Melancholic. Have you always longed to be Sanguine only to be told that you are Choleric? Yeh, me too. The Humors are actually liquids - blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. The liquids were balanced when a person was healthy. Humors also determined a person’s mood and character. Melancholy, just so you know, was associated with black bile, the least desirable of the four liquids. In the middle ages, melancholics were considered the most likely to go crazy. In the Renaissance, Melancholia was linked to creative genius. Which is probably how Dürer thought of her and himself.

Figure 5. Melancholia I, Albrecht Dürer, 1514

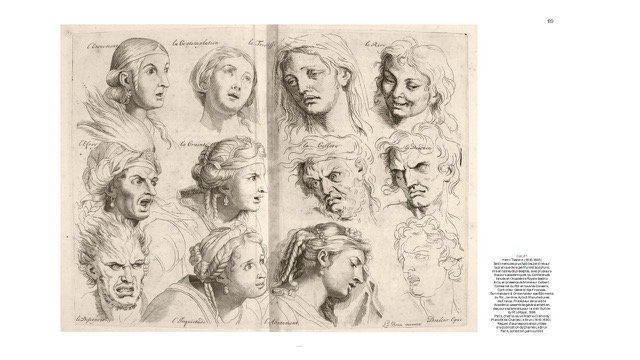

Proust couldn’t find expressions or emotions in the Virtues and Vices in the Arena Chapel. Because they didn’t have any. That wasn’t the point. But it would become the point of an artist who worked in France a century later. Louis XIV’s court painter, Charles LeBrun, who Louis XIV called "the greatest French artist of all time”. Maybe. Hard to tell since most of his yards (meters) of paintings are in storage somewhere in the Louvre. Le Brun’s compendium called ‘Têtes d’Expressions,’ was first published in 1668. With LeBrun it’s not what you carry that counts, but how you carry yourself that matters. Not so much with Justice and Charity but definitely with Envy and Terror. (Figures 6, 7)

Figure 6. Têtes d’Expressions, Charles LeBrun, 1668

Figure 7. Horreur, Têtes d’Expressions, Charles LeBrun, 1668

Charles Le Brun codified how people actually manifest feelings. The face was infused with emotion and then so were the hands and finally the entire body. Louis-Léopold Bouilly, about whom I wrote a few weeks ago (A Jack of All Trades) and who is having his own moment at the moment, inherited Le Brun’s methodical madness. And it is at his hand that the whole thing becomes hilarious, in Trente-cinq têtes d’expression (1825) and also Les Loges au Théâtre and l’Effect du Mélodrame (both 1830). (Figures 8, 9 10) He has fun describing and caricaturing facial expressions and sometimes gestures of people from all rungs of society. We go from suffering to joy, from enthusiasm to terror, from pleasure to pain. These people may be watching a performance, but it is their reaction, their performance, that captivates us.

Figure 8. Trente-cinq têtes d’expression, Léopold Boilly, 1825.

Figure 9. Les Loges au Théâtre, Léopold Boilly, 1830

Figure 10. L'Effect du Mélodrame Léopold Boilly, 1830

The cartoonist Honoré Daumier, was a master of facial expressions, hand gestures and body language, too. All essential components of cartoon and caricature. Daumier mocked through exaggeration. The working classes, from which Daumier never forgot he came, were treated with humor and sometimes, gentleness. The lawyers and politicians received most of his disdain and wrath.

Among the prints by Daumier in this exhibition is Rue Transnonain, 1834. (Figure 11) Demonstrations in Lyon led to riots in Paris. On April 14, near a barricade in rue Transnonain, an infantry captain was apparently wounded by a shot fired from a window in an apartment building on rue Transnonain. In retaliation, soldiers raided the building. Twelve of its fifty inhabitants were massacred by the soldiers. The dead included women and children, elderly and disabled men. Daumier’s print is not a factual account but a stark composite of who had died and perhaps how they were found. A dead man in his bedclothes, a dead child underneath him. The head and shoulders of an elderly man on the right, also dead. A dead woman whose bare feet we see in the shadows on the left. The government seized all the prints they could find as well as the lithograph stone from which they were printed. Making sure there would be no more. The government then passed new laws proscribing political caricature. As a result, Daumier changed his subject matter, turning his eye away from direct political critique and toward social commentary. Which are here, too. (Figures 12, 13)

Figure 11. Rue Transnonain, Honoré Daumier, 1834

Figure 12. Le Ventre Législatif, Honoré Daumier, 1834

Figure 13. Eloquence Fulchironne, Honoré Daumier, 1835

As we move through the exhibition, facial expressions and positions of the arms, hands, and body tell the story. With Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s Le Verrou , (1777), a man locking a woman’s bedroom door, impeding her escape is pretty clear. (Figure 14) And yet, things, ‘stuff’ don’t entirely disappear. We have only to look at paintings by Greuze and by those who painted in the style of Greuze to see broken bottles, spilled milk, dead birds, all signifying that we are observing a woman who’s having some profound regrets about the night before. (Figures 15, 16)

Figure 14. Le Verrou. Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1777.

Figure 15. Dead Bird

Figure 16. Girl with Bird, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, ca. 1800

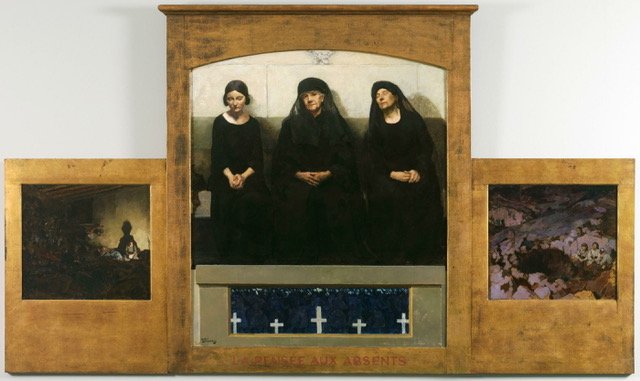

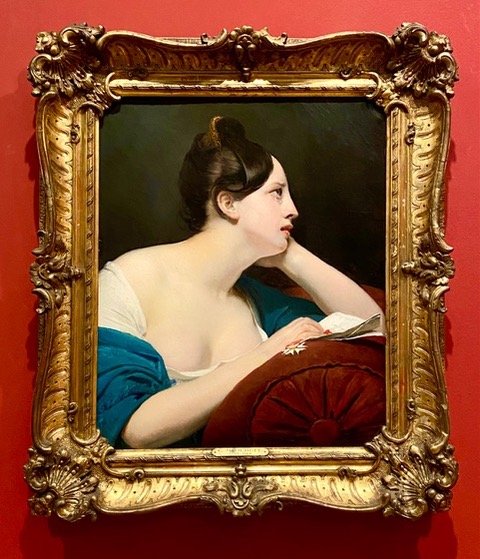

The exhibition offers a range of images from the 19th century, of individuals and groups that refer to private and public moments of illness and despair, from alcoholism and prostitution to plagues and wars. (Figures 17, 18) As one critic noted, in the early 19th century, the so-called romantic period, the paintings and prints and sculpture focused on the emotions of the people depicted. Claude Marie Dubufe’s 1827 La Lettre de Wagram (a particularly bloody battle during the Napoleonic Wars which the French won but at enormous cost in lives) (Figure 19) for example, shows a young woman shedding real tears, reading a letter, not comforted one bit by the medal for bravery that accompanied it. The painting Faim, Folie et Crime (Hunger, Madness and Crime) is horrific. (Figure 20) A grinning young woman holds a bloodied knife in one hand, the corpse of a baby on her lap.The baby’s foot is in the pot in the fireplace. This is postpartum depression on speed. The Donner Party on a domestic scale. A rare combination of infanticide and cannibalism.

Figure 17. Pornokrates (or La Dame au Cochon), Felicien Rops 1879, Muse into Prostitute

Figure 18. Le Pensée aux absents triptych. Andre Devambez, 1927. Daughter, Mother, Wife in mourning

Figure 19. La Lettre de Wagram, Claude M. Dubufe, 1827

Figure 20. Faim, Folie et Crime, Antoine Wiertz, 1853

Then something began to happen, the arts gradually moved away from naturalism. Artists no longer sought to show an emotion, they sought to provoke one, in the viewer. Like Pablo Picasso (Figure 21) represented here by Le Suppliant, a figure that combines a Greek chorus with Guernica. A plea for pity, for salvation. Salvatore Dali’s images (Figure 22) often bizarre, usually incongruous combinations of elements always provoke a reaction. The German expressionist painter Jawlensky’s use of colors (Figure 23) which do not define or describe reality, evoke feelings in the viewer.

Figure 21. La Suppliant, Pablo Picasso, 1937

Figure 22. Salvador Dali

Figure 23. Woman’s face, Alexej vonJawlensky, 1911

So, to recap, we begin with attributes, either carried or cluttered around a figure, usually female. Like words, you ‘read’ the attribute to understand the meaning. Stage two is expressions, mostly facial although arms soon join in, then legs and torsos. No longer is it an abstract ideal or set of ideas that is being expressed but an emotion, a sentiment. Things continue to move along and eventually ‘body language’ tells the whole story. Accessories and vignettes don’t disappear, of course. They are included to insure that the viewer understands the emotion the artist wishes to convey, whether sexual aggression or marital harmony. Things have gotten more complicated over the years, as signifiers become more abstract and it is the emotions felt by the viewer rather than experienced by the viewed, that artists solicit. Now, your response to a work of art is as valid as anyone else’s. You respond, you react, you interpret.

The exhibition at the Musée de la Vie romantique is more focused. (Figure 24) Historical and fictional heroines in 19th century in painting and sculpture, in literature and on stage. Please don’t expect to see super heroines, like Cat Woman and Wonder Woman. Because even women whose bravery entitles them to the title of heroine, it is what happens to them after those courageous acts that are depicted here. Not Jean d’Arc leading the troops but Jean d’Arc tied to the stake. (Figure 25) Not Charlotte Corday stabbing Marat but Charlotte Corday awaiting the guillotine.

Figure 24. Héroïnes romantiques, Musée de la Vie Romantique

Figure 25. Jean d’Arc tied to the stake

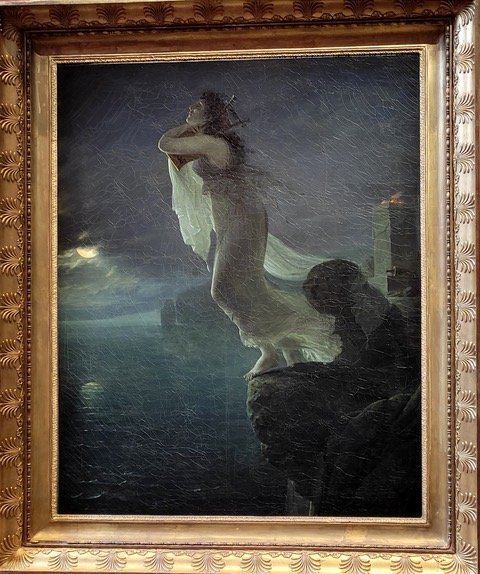

Antoine-Jean Gros’ Sappho, (Figure 26) shows the poetess of Lesbos, about to hurl herself into the sea. Why? Because after having sex with her, Phaon rejected her. Yes she was distraught but she believed that if she jumped into the sea, she would either be cured or drowned. She drowned. Sounds like the Salem Witch trials. Throw a suspected witch into water, if she sinks she’s innocent, if she floats, she’s guilty. Either way, she’s dead.

Figure 26. Sappho, Antoine-Jean Gros

Then there’s Jean Gigoux’s Cleopatra, (Figure 27) the Queen of Egypt for 20 years, who influenced Roman politics through her relationships with Julius Caesar and Mark Anthony. But here it is her suicide that matters. Lying nude, her face hidden, her hair undone, her skin white, her death imminent. Posed for our delight and delectation.

Figure 27. Cleopatra, Jean Gigoux

One critic posits that the period’s fascination with the tragic stories of romantic heroines was rooted in the reality of women’s lives in the 19th century. A time when women had almost no legal rights, being successively the charge of their fathers and the property of their husbands. How else would a woman who reached for passion or heroics end up? Like Emma Bovary, of course, Gustave Flaubert’s heroine whose efforts to find a life of passion and freedom ended in suicide. And so of course, we have all these heroines in diaphanous gowns or nude, fragile and resigned. (Figures 30, 31) Mostly painted or sculpted by male artists.

The temporary exhibition space at the Musée de la Vie romantique is intimate, even a little bit romantic. Up a narrow circular stair in the middle of the main space, and you are in a delightfully (even romantically) decorated room which celebrates the performances of actors, ballerinas and opera singers. There’s a portrait of the famous Mlle Rachel, who also makes an appearance at the Marmottan Monet exhibition in her role as Lady MacBeth (Figures 28, 29) The story of these performers and the roles they played is told through photos, film clips and costumes. (Figures 30, 31). This is a well done, beautifully presented exhibition. As with others I have seen here, it tackles a narrow subject expansively - through art, literature, music and theater. And the permanent collection which focuses on George Sand, is fun and free. What’s stopping you? Go now, while this exhibition is still on.

Figure 28, Mademoiselle Rachel as Lady Macbeth, Charles Louis Müller, 1849 (Marmottan-Monet)

Figure 29. Mademoiselle Rachel as Phadré, (Musée de la Vie romantique) 1850

Figure 29. Mademoiselle Rachel as Phadré, (Musée de la Vie romantique) 1850

Figure 31. Statue of Marie Taglioni dancing La Sulphide, 1837

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.