Never mind the Madeleine.

Proust Coté de la mère, part 2

The Book of Esther

The MahJ has a mezzanine between the two main exhibition spaces. Which obviously needs something pertinent. This time it’s the story of Queen Esther. As you’ll remembr, the Persian King Ahasuerus married the beautiful maiden, Esther. Mordecai, Esther's uncle, learned that the king’s advisor Haman planned to massacre the Jews. Mordecai asked Esther to intercede on behalf of her people. Esther agreed even though asking for an audience with the king was tricky. If he didn’t want to see you, he could have you killed. But Ahasuerus is not angry. His young bride is beautiful. (Figure 1) Although he is surprised to learn that she is Jewish. Esther begs Ahasuerus to spare her people. He does and hangs Haman instead.

Figure 1. Esther before King Ahasuerus

At first I thought the connection was just that Esther was Jewish and Proust’s mother was Jewish. But no, there’s more. Jeanne admired this Old Testament heroine and was especially fond of the version of Esther’s story penned by Racine in 1689, for the young ladies in the seminary at Saint-Cyr founded by Mme Maintenon.

In 1905, Sarah Bernhardt, the inspiration for Berma in La Recherche du Temps Perdu, staged Racine’s Esther with all the roles performed by women, as they had been originally. (Figure 2) Proust’s friend and lover, the musician Reynaldo Hahn wrote the music for Bernhard’s performance which he reprised at Proust’s home that same year. This little exhibition includes a contemporary artist’s interpretation of Purim, Jewish Halloween. I learned about its connection to Mardi Gras and role reversals, when the lowly take the role of the mighty and vice versa. It’s fascinating, wish I could tell you more. (Figure 3)

Figure 2. Sarah Bernhardt as Queen Esther

Figure 3. Charles Haas

The Jewish Characters in In Search of Lost Time

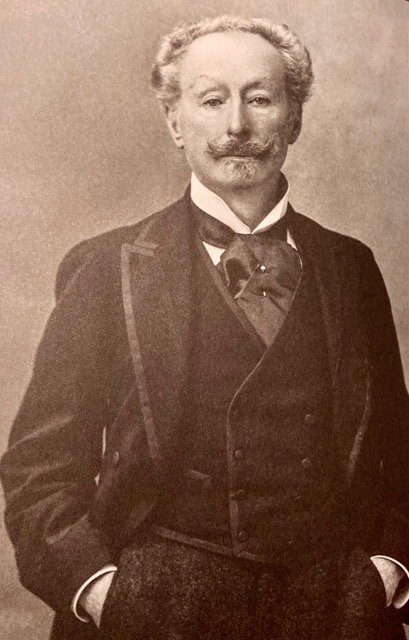

Let’s talk about the model for the character of Swann in In Search of Lost Time. Most Proust scholars agree that Charles Swann is based on two men, Charles Haas (Figure 3 above) and his nephew Charles Ephrussi. Let’s start with the older contender, Charles Haas. The exhibition includes the large group portrait commissioned in 1868 from James Tissot of the members of the Cercle de la rue Royale, (Figure 4) a gentleman's club, founded in 1852. And one of the few that accepted Jews. The men are on a balcony of the Hôtel de Coislin overlooking the Place de la Concorde. Charles Haas is at the far right of the canvas. He is the only Jew. He is the only non-aristocrat.

Figure 4. Cercle de la rue Royale, James Tissot, 1868

One modern critic calls Haas the kind of guy who was famous at the time for being famous and about whom we know so little now because he did so little. And we thought that the internet invented people like Haas! But Haas did impress Proust enough that he cast him as well as his nephew for the character of Swann. In the fifth volume of In Search of Lost Time Proust wrote, "it is already because someone whom you must have considered a little idiot has made you the hero of one of his novels that people are beginning to talk about you again, and maybe your name will live on."

In reference to this group portrait, Proust wrote, “If people talk so much about the Tissot painting, it is because they can see that there is something of you in the character of Swann.” According to Proust, non-aristocrats seldom lived past their time, unless they were immortalized in poetry or art. As Haas was by both Tissot and Proust.

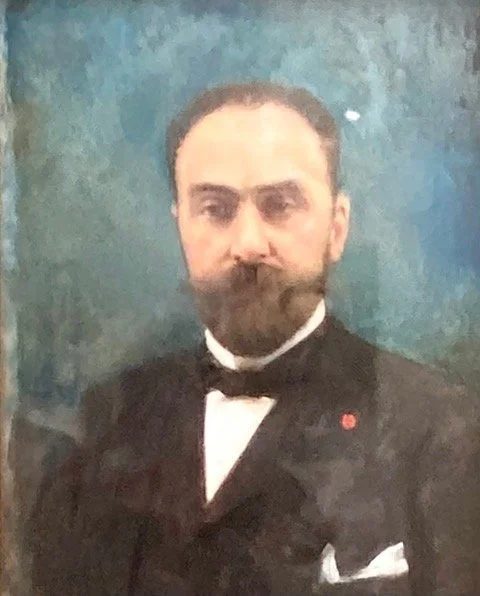

The other model for Swann, Charles Ephrussi, (Figure 5) differed in nearly every way from his uncle. Since he actually did something, quite a lot in fact. He was an art historian and art collector. He owned and edited the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, the most significant art periodical in France at the time. But there are similarities, Ephrussi’s friends included European leaders and like his uncle, he was a frequent guest at the best salons of Belle Epoque Paris.

Figure 5. Charles Ephrussi, Leon Bonnat, 1906

Elizabeth Melanson has studied the connection between impressionism and Jewish art collectors, in life and in Proust. For example, in volume three of In Search of Lost Time, the narrator is having lunch with the aristocratic couple, the Duke and Duchess de Guermantes. I don’t know what all he is eating, but he has definitely been served asparagus.

The Duke see the narrator looking at one of their paintings. The narrator asks the Duke if he knows the name of the man wearing the top hat. (Figure 6) “Good Lord, yes,” he replied, “I know it’s a fellow who is quite well-known… As a compliment to this man - if you can call that sort of thing a compliment -( the artist) has painted him standing among that crowd …He may be a big gun in his own way but he is evidently not aware of the proper time and place for a top hat.…(H)e looks like a little country lawyer…” The painting they are talking about is Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party. And the man in the painting who the Duke is mocking is Charles Ephrussi.

Figure 6. Luncheon of the Boating Party, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1881

The Duke talked about another painting, too, which he says “Swann had the nerve to try and make us buy” It was “… just a bundle of asparagus exactly like the ones you’re eating now.” The Duke is obviously talking about the painting by Manet, Bunch of Aspargus, which Ephrussi owned. I’ve told the story before, how Ephrussi was so pleased with it that he sent Manet 200 francs more than the agreed upon price. Manet responded by sending Ephrussi another painting, a much smaller one, of a single asparagus stalk with the note, “There was one missing from your bunch”. (Figures 7, 8)

Figure 7. Bunch of Asparagus, Edouard Manet, 1880

Figure 8. Asparagus, Edouard Manet, 1880

Melanson contends that it was wealthy Jewish art collectors’ enthusiastic support of Impressionism that led to Impressionism’s popularity in the 20th century. She further suggests that the tradition of collecting modern art and donating it to state museums originated with Jewish art patrons. So, next time you are at the Musée d’Orsay, for example and you are looking at the name of a painting and who painted it, take a look at the painting’s provenance. To see how the painting came to be in the museum’s collection. The name Ephrussi appears with some regularity.

In addition to Manet and Renoir, Charles Ephrussi particularly appreciated Degas. In 1883, he financed Degas’ first subscription and backstage pass to the Opera. (Figure 9) I’ve written about those subscriptions and passes which permitted wealthy and lecherous men, old and young, but mostly old, to watch ballerinas practice, to chose among these tiny girls which they would bed and support.

Figure 9. The Dance Lesson, Edgar Degas, ca. 1879

Ephrussi did not collect Pissarro. (Figure 10) He said it was because Pissarro’s paintings were not gay and lively like those of Morisot, Cassatt and Degas. That “he makes the spring and flowers sad and the air heavy…” Was Pissarro just too Jewish?

Figure 10. The Gleaners, Camille Pissarro, 1889

Proust’s character Bloch has led critics to call Proust an anti-semite. Proust was making distinctions between the Jews he associated with, like Charles Ephrussi, who wore their Judaism lightly or not at all. And those who fit the cruel stereotypes. Here is how Proust describes Bloch in Swann’s Way, “Ah yes, that boy I saw once here, who looks so much like the portrait of Mahomet II by Bellini. (Figure 11) Ah! It’s striking, he has the same circumflex eyebrows, the same curved nose, the same high cheekbones. When he has a goatee it will be the same person.” Anti Semite, not anti Jew.

Figure 11. Mahomet II, Gentile Bellini, 1480

Proust and the Dreyfus Affair

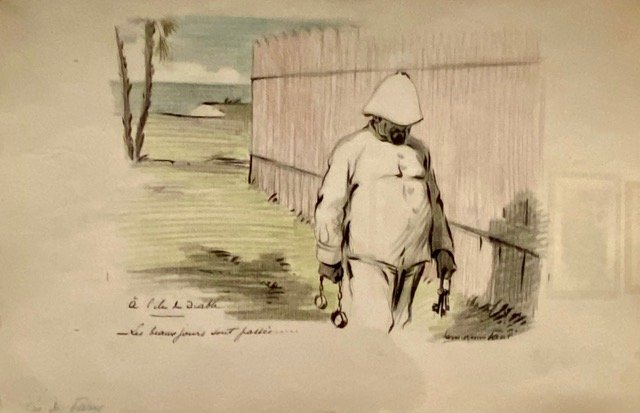

And on the subject of anti-semitism. Alfred Dreyfus was a Jewish captain in the French army. (Figure 12) In 1894 he was accused of espionage and found guilty of high treason. He was sentenced to solitary confinement on Devil's Island. (Figure 13) Soon discrepancies about his conviction appeared and people began questioning his conviction. But not everybody. There was a deep division between the Dreyfusards, who demanded a retrial and the anti-Dreyfusards, who defended the government. In 1898, Emile Zola published an open letter, ‘J’accuse' to the President of the French Republic which appeared in the newspaper Aurore. (Figure 14) In it, Zola accused the government of anti-semitism and the unlawful jailing of Dreyfus. Zola was put on trial and found guilty of libel. He fled France for England. Later that same year, the man who faked the evidence against Dreyfus confessed and committed suicide. Finally the government ordered a retrial. Dreyfus was found guilty, again. Impossible for the government to admit a mistake. This time, the President pardoned Dreyfus. It wasn’t until 1906, after 12 long years, five of them on Devil’s Island, that Dreyfus’s rightful military rank was restored.

Figure 12. Alfred Dreyfus Degraded, 1896

Figure 13. Alfred Dreyfus’ jailor on Devil’s Island, 1896

Figure 14. ‘J’Accuse,’ Emile Zola, L’Aurore, January 13, 1898

Proust signed a very public petition calling for a retrial. By doing so, Proust angered his conservative, Catholic, pro-army friends and alienated his father, an anti-Dreyfusard. Proust’s choice, one also taken by his brother Robert and his mother, was more a matter of conscience than of religion.

The Dreyfus Affair brought anti-semitism in France to the surface. Of the Impressionists, the Dreyfusards included Cassatt, Monet, Signac and of course, Pissarro. The anti-Dreyfusards included Degas and Renoir, Rodin and Cezanne. The most virulent was Degas. His vitriol against Camille Pissarro, formerly a dear friend, is horrifying. No wonder Julie Manet, Berthe Morisot’s daughter, dependent upon Degas and Renoir after her mother died, wrote in her diary that she couldn’t imagine that the French army was wrong. If you were Catholic, you trusted the Army and the government There was no separation between church and state as long as that church and you were Roman Catholic.

Proust and Homosexuality

The Narrator in In Search of Lost Time is neither Jewish nor homosexual. Proust was both. He adored his mother but distanced himself from her religion. He was a homosexual, but challenged a homosexual writer to a dual for accusing him of having a homosexual relationship with another homosexual. Whew. Hidden identity is exhausting. But as one writer noted, in Proust’s time, Jews and homosexuals were subjected to the same level of stigmatization. A level which constrained them both to the greatest discretion. And for anyone who thought honesty might be the best policy, they had only to look at Oscar Wilde. His trial and incarceration in England on charges of sodomy. In 1897, it was a broken and broke Wilde who arrived in France. He died three years later, at age 46.

But homosexuals, both flagrant and closeted make their appearance in Proust’s novel. The character of Baron de Charlus was inspired by Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac. (Figure 15) Twenty years Proust’s senior, he was an aristocrat, a poet, an intellectual and an art collector. Oh, and a dandy and a closeted homosexual. In the Proust exhibition at the Carnavalet, there was a clip from a film adaptation of Proust's opus showing the Baron de Charlus being whipped at a male brothel. He seems startled at first but then he seems to like it. This ‘temple of shamelessness’ as Proust calls it in his novel, had its origin in real life, Proust’s real life. Proust was recorded in a police report of January 11, 1918 as having been at the Hotel Marigny when it was raided by the police. This ‘hotel’ was where homosexuals of all classes and tastes could meet and have their pleasures realized. According to one writer, Proust’s visits to the Hotel Marigny were for research only - to learn about the fantasies of the customers who made their way there. The owner organized voyeurism sessions for Proust. At one such session, he watched a wealthy man being beaten until he bled. This was the scene that was reenacted in the film clip I saw at the Carnavalet starring the Baron de Charlus and his hired tormenter.

Figure 15. Count Montesquoiu, Lucien Doucet, 1879

The Ballet Russes

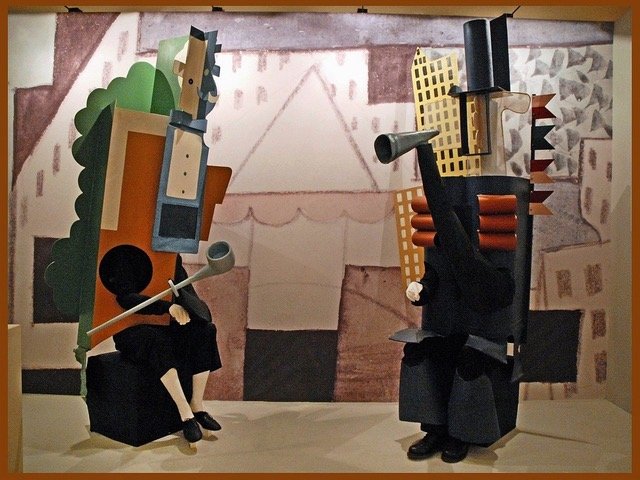

And then there is Proust’s fascination with the Ballets Russes. But alas, art is long and time is short, so I will only tell you that after attending a performance of the ballet Parade (Figure 16) which featured costumes by Picasso, Proust wrote in a letter, “comme Picasso est beau.” Picasso was only 10 years younger than Proust although he died 50 years after Proust did. We are marking the centennial of Proust’s death this year. The 50 year anniversary of Picasso’s death is next year. Proust is our guide to a seemingly distant place and time. Picasso is still the father of modern art.

Figure 16. Costumes for ballet ‘Parade’ Ballets Russes, Pablo Picasso, 1917

The Madeline

And now a word about the madeleine. (Figure 17) Proust’s madeleine moment appears at the beginning of his seven volume opus, in Swann’s Way. Here’s the passage: “(Mother) sent for one of those squat plump little cakes called ‘petites madeleines,’ which look as though they had been molded in the fluted valve of a scallop shell … I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure invaded my senses … And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray … when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Leonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane …. and the whole of Combray and its surroundings, taking shape and solidity, sprang into being, town and garden alike, from my cup of tea.

Figure 17. Ubiquitous, iconic madeleines available everywhere!

Turns out, the ‘morsel of cake’ that triggered Proust’s memory and through which we are encouraged to have our own ‘Proustian moments’ didn’t start out as a madeleine at all. In his first draft, the trigger for the author’s childhood memory was toasted bread mixed with honey. In the second draft, it was a dry biscuit. It wasn’t until the third draft that Proust decided that only a madeleine would do. And just in case you were thinking of trying this at home, don’t. Madeleines don’t crumble in tea, no matter how hot the tea, too much butter. So, let it go and find your memories where you may.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.