Talking to Tables and Confronting Picasso

Contemporary artists take on the permanent collections of the Musées Marmottan-Monet, Guimet & Picasso

Today we are going to talk about three temporary exhibitions. Which are not like the ones I usually write about. That is to say, they are not exhibitions conceived and coordinated by academics and curators about a particular artist or a particular theme. Exhibitions which may or may not have any connection to the museums’ own permanent collections.

The exhibitions I am going to talk about today are ones that were conceived and created by contemporary artists who were invited by the museums to enter into conversation with some aspect of those museums’ permanent collections. While traditional temporary exhibitions get you into a museum, these temporary exhibitions remind you to take a look, while you are there, at the permanent collections, too.

We’re going to look at contemporary artists’ responses at the Musée Marmottan-Monet, (in its 5th year of collaborations), the Musée Guimet (its 15th year of collaboration) and the Musée Picasso (its first collaboration). The ones at the Marmottan-Monet and Picasso will be here this summer for you to see. The one at the Guimet has just closed but it will give you an idea of the kinds of collaborations that museum offers. And the artist took as her theme one that particularly interests me: What she did when everything came to a stop during the Covid confinement.

Let’s begin with the Musée Marmottan-Monet. I happened upon the first collaboration at this museum quite by accident a few years ago when I was there to see an exhibition on depictions of Childhood or maybe it was on the Orient. Anyhow, the collaboration was on the sous sol level where Monet’s waterlily paintings hang. Where, I must confess, I didn’t always go when I was at the museum. But I fell in love with that exhibition. Now I always visit the Waterlilies when I’m at the museum, to see what’s new.

Here is how that first collaboration came about. The artist Gérard Fromanger (who died a year ago this month) was at the museum, as the director’s guest. He stopped in front of a painting by Gustave Caillebotte, one that everyone loves now (maybe its all those umbrellas) ‘Paris Street, a rainy day’. (Figures 1, 2) It was a subject that Fromanger had made his own over the years. (Figure 3)

Figure 1. Gustave Caillebotte, ‘Paris Street, a rainy day’ 1877

Figure 2, Caillebotte umbrella, Amazon

Figure 3. Gerard Fromanger, Printemps, 1972

His initial idea was to paint what he called, “with four hands”, that is, ‘riffing’ off this painting and others whose subjects interested him. He suggested it to the Museum’s director and curators. At exactly the right moment. The decision had already been made to invite a contemporary artist, twice a year, to create works that resonated with the museum’s permanent collection.

The collaborations are called “unexpected dialogue”. Fromanger nestled his own work, Boulevard des Italiens, 1971(Figure 4) between Caillebotte’s painting and Pissarro’s Boulevard exterieur, effet de neige. For Caillebotte and Pissarro, it was Haussman’s Paris. For Fromanger it was the Paris of the 1970s . The theme is the same, the language is different. And to this Fromanger added portraits of artists, like Sisley, Renoir and Cézanne; Monet, Caillebotte, Pissarro and Morisot. (Figures 5, 6) His was a portrait gallery made of lines of vibrating primary colors. And there was also a riff on Monet’s iconic Impression Sunrise, “a giant canvas (with) a miniature crowd walking among the stars replay(ing) the impression of Monet, his way. (Figures 7, 8)

Figure 4. Gerard Fromanger, Boulevard des Italiens, 1971

Figure 5. Gerard Fromanger, Claude Monet, 2019

Figure 6. Gerard Fromanger, Berthe Morisot, 2019

Figure 7. Gerard Fromanger, Impression Sunrise

Figure 8. Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise, 1872

Monet and Impressionism has been the focus of all sorts of ‘unexpected dialogues’ over the years. This year, Hélène Delprat decided to mix it up and enter into a conversation with the dining room table in this, the former residence of Paul Marmottan, in the room where Caillebotte’s rainy painting holds court. Actually it is the gilt bronze centerpiece on top of the table that intrigued Delprat, that caught her creative eye and inventive mind. (Figure 9) Three sets of dancing bacchantes holding flambeaux, two sets make their graceful way around candelabras at either end. The central group, equally graceful, is disposed around an open lattice work vessel. At each corner, stands a goddess holding attributes, like a horn of plenty and a scythe. Finally, between each goddess, naked putti cavort. Delprat’s response to this table decoration looks, as one critic noted, more like a film set than a centerpiece. Mirrors, clay and paper objects, gold chains and swords, busts, models, etc. make her table a ‘theater of operations’. (Figures 10, 11, 12)

Figure 9. Pierre-Philippe Thomire, Centerpiece of dining table, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Figure 10. Hélène Delprat, Conversation with a table, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Figure 11. Hélène Delprat, Conversation with a table, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Figure 12. Hélène Delprat, Conversation with a table, Musée Marmottan-Monet, detail

Maybe her inspiration was Napoleon and his battles. Which makes sense because before this hotel particular became a museum filled with paintings by Monet, Morisot, etc. it housed (and still does) the Marmottan collection of Napoleonana, pieces of which are on display throughout the museum. Of which the table centerpiece designed by goldsmith Pierre-Philippe Thomire, is one. When I saw the exhibition, it was after the war in Ukraine had started. When the reality that it was likely to be a long war, was beginning to sink in. To see references to war here and like this, was timely and chilling. Check out: Hélène Delprat, conversation with a table.

And now let’s go to the National Museum of Asian Arts Guimet, where for its 14th Carte Blanche to Contemporary Art, the museum invited the Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota to make something. Her thing is thread which she weaves to create weblike, architectural spaces. The spaces she creates invite us to simultaneously reflect on the links that connect us and the screens that separate us.

I was eager to see what she had created for the Guimet because I really liked her exhibition at Le Bon Marché in January 2017. In response to an invitation the store offers once a year to a different contemporary artist to coincide with the store’s annual white sales. For that exhibition, Shiota’s themes were travel and the sea using 150 woven boats encircled by gigantic waves of steel. (Figure 13) The idea was that humans are carried towards their destiny through experiences and encounters that often upset their course. Shiota uses black thread to represent the “outside universe” and red thread to represent her “inner universe”. This time, she incorporated white thread, a symbol of purity and here a reference also to the white sales, a sign of new beginnings.

Figure 13. Chiharu Shiota, Le Bon Marché, 2017

Shiota’s work at the Guimet is scattered throughout the museum. As at Le Bon Marché, there is one grand piece. This one is in its own gallery, accessible by a fairly narrow circular stairs.

As for most of us, Covid and confinement represented restrictions as well as challenges for the artist. In this installation, entitled ‘Living Inside,’ the color black, representing the outer universe for Shiota is gone. Here, there is only red, the color of her inner universe. And with only red thread, Shiota has created an architectural web that connects and separates tiny pieces of dollhouse furniture, like beds, chairs, pianos, toilets, etc. (Figures 14, 15) The architecture is Brobdingnagian, the objects trapped in its web are Lilliputian. Everything is held captive by threads that protect and isolate. This is about domestic spaces, about the family cocoon. About the protective network the artist had spun around herself and her family. There is a sense of isolation, maybe even desperation. Which so many of us felt, but not David Hockney. He had his house and his garden in the French countryside. Nobody canceled spring. (Figure 16)

Figure 14. Chiharu Shiota, National Museum of Asian Arts - Guimet, 2022

Figure 15. Chiharu Shiota, National Museum of Asian Arts - Guimet, 2022, sink and toilet detail

Figure 16. David Hockney surrounded by some of his paintings from Covid Confinement

And now, our third contemporary artist’s conversation with a museum’s permanent collection. I bumped into it accidentally last week when I was at the Musée Picasso to see the exhibition about Picasso’s relationship with his oldest daughter, Maya. Which started out great but ended up not so great.

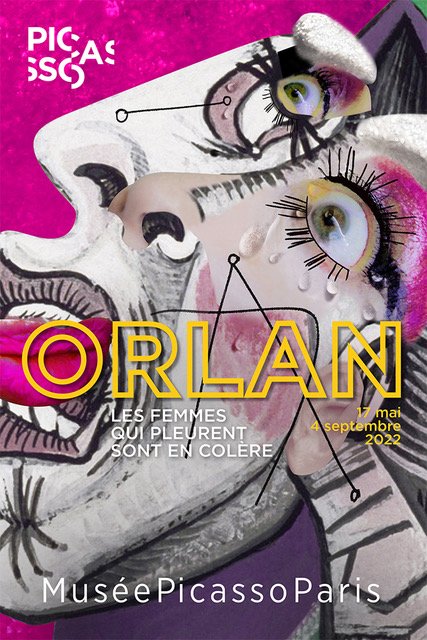

The exhibition I am going to talk about was easy to miss, it’s in the basement. The subject, Picasso as misogynist. It’s not a new topic. But the voices raised against him have become louder since #MeToo. Being old, even being dead doesn’t keep the reckoners away. Finally, the museum could ignore the issue no longer. The Picasso Museum in Barcelona organized a seminar in May about Picasso's relationship with women. The Picasso Museum in Paris invited the feminist artist ORLAN to re-consider the artist’s oeuvre. (Figure 17) Both museums should have done both.

Figure 17. ORLAN, Les Femmes Qui Pleurent sont en Colère, (The Crying Women are angry), Musée Picasso Paris, 2022

ORLAN’s exhibition consists of two photographic series, ”ORLAN hybridizes with Picasso’s portraits of women" and "Weeping women are angry" (from 2019).

Figure 18. Leonardo, Mona Lisa, 1503

Have you heard of ORLAN? She works with all kinds of media from traditional: painting, sculpture and photography to avant-garde: installations, digital images and artificial intelligence. And performance, which includes filming her face changing surgeries, which she had and filmed from 1990-1993.

Figure 19. ORLAN

Women have historically been the object of the male gaze. A woman’s body has traditionally been presented to the (presumed male) viewer, as nude, recumbent and passive. ORLAN won’t have any of it. For the past five decades (she was born in 1947), she’s been in charge of her own image, her own body. Which brings us back to those surgeries. Here’s what some of them were about. One was to get the mouth of François Boucher’s Europa, another the chin of Botticelli’s Venus, a third was for the protruding brow of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. (Figure 18) The forehead transplants by which she is best known, well, along with her Cruella de Vil hairdo, are from the Mona Lisa operation. (Figure 19) These little implants are usually used as cheekbone enhancers. She has them on both sides of her forehead. She has fun with them, painting them, mostly with eye shadow. But why? To be more beautiful, more acceptable to the male gaze.? Certainly not according to ORLAN. Her goal was to be in charge of her own appearance. To be both the observer and the observed. She documented each surgery on film. She was awake. She’s a fervent believer in pain killers. She explained it to one interviewer this way, "All my life … men were always coming first. Not to talk about feminism would mean that I didn't respect myself.”

Okay. Back to ORLAN and Picasso. Since she has spent so much of her career talking about and creating art that denounces the violence done to women and their bodies, there was a lot for her to respond to with Picasso. Her exhibition revisits Picasso's work so that "women who suffer come out of the shadows.” One of her sets of photographs is a riff off Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’ series from the late 1930s. (Figures 20, 21) Picasso’s paintings and drawings are mostly of Dora Maar, his mistress and muse at the time. She was a gifted photographer. Her relationships with domineering men like the photographer Man Ray with whom she worked and with Picasso, were destructive. She became more and more fragile, more and more depressed. Which suited Picasso just fine since he was using those portraits of Maar for his masterpiece, Guernica (1937), (Figures 22) a denunciation of the Spanish Civil War and fascism.

Figure 20. Picasso, Weeping Woman (Dora Maar) 1937

Figure 21. ORLAN, Weeping Women are angry, 2019

Figure 22. Picasso, Guernica, 1937

Rather than focus on Guernica, ORLAN uses photographic montages to focus on Picasso’s relationship with Dora Maar. According to ORLAN, she created her “Weeping women are angry" series of hybrid photographs to "showcase the women who are always in the shadows: the inspirers, the models, the muses." Sure his paintings of Dora Maar inspired a painting whose subject is the murder of civilians at Guernica but ORLAN doesn’t believe you can ignore that they also reflect Picasso's violence towards his partner. "Through Picasso's portraits of Dora Maar crying, I wanted to make works where the women who suffer suddenly come out of the shadows and suffer. They revolt and emancipate themselves, become subjects instead of being objects” (Figure 23)

Figure 23. ORLAN, 2022

ORLAN transformed Maar’s tears of grieving and sadness into tears of anger. “My creations,” says ORLAN, “all political and feminist, are based on a visual research of faces of horror, fear and grandeur. Picasso objectifies Dora Maar. I reread Picasso's work to put the woman-subject back at the center. Between painting and photography, tears and anger, my female figures are…extremely free and unbridled." (Figure 22)

Figure 24. ORLAN From Weeping Women series, 2019

Here is how Cécile Debray, director of the Picasso Museum in Paris sums up ORLAN’s work. "She speaks of hybridization, It’s a very strong and pop way of re-reading Picasso's work by denouncing it and glorifying it at the same time…The works will undoubtedly lead visitors to take another look at the paintings of the most famous painter of the 20th century… (T)he museum … must defend Picasso's work and at the same time pass it on to future generations, (to) keep it alive."

That is exactly what these museums and others are doing. Temporary exhibitions in their spaces bring people (back) into the museums. By inviting contemporary artists to create pieces that reflect upon the permanent collections, the museums insure that their own collections stay relevant.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.