Marvelous Marseille.

The sky, the sea, the museum (MUCEM)

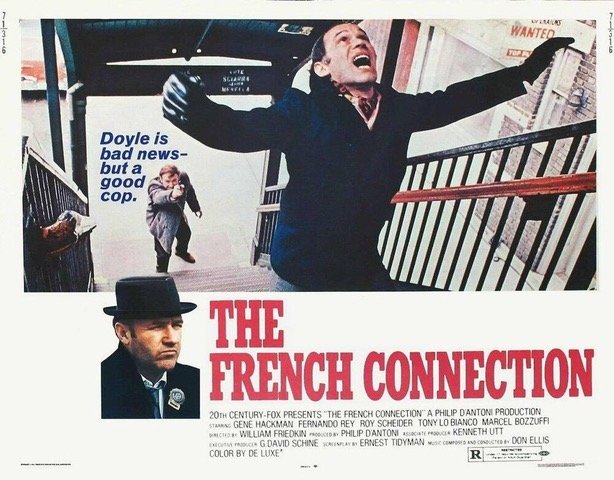

Your introduction to Marseille may have been William Friedkin’s thriller, The French Connection. The film in which Gene Hackman as Popeye Doyle asked that unforgettable question: ‘Did you ever pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?’ (Figure 1) The film was based on a true story, about two cops shuffling between New York and Marseille trying to take down a large heroin smuggling operation. The film was shot in New York and Marseille. New York was rundown, Marseilles was menacing.

Figure 1. The French Connection film poster, 1971

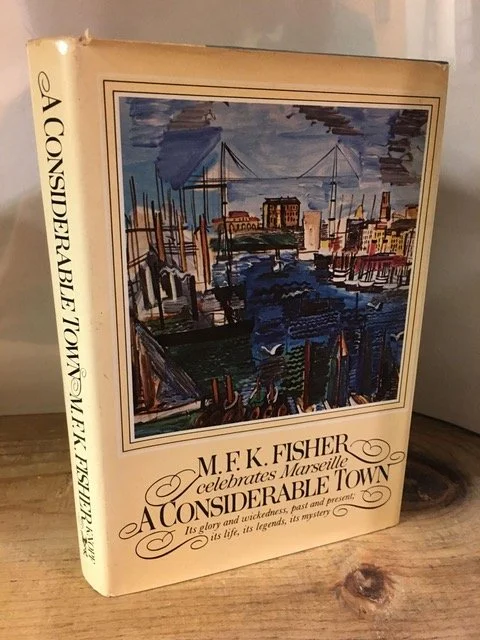

The film came out in 1971. I saw it, of course, but I’m not sure I even registered that the French town was Marseille. My real introduction to Marseille was M.F.K. Fisher’s book, A Considerable Town, (Figure 2) which I probably read in the 1980s. I eventually became quite obsessed with the author. Have you heard of Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher? Or read any of her books? She was born in Albion, Michigan, moved with her family to Whittier, California and with her new husband, Al Fisher, to Dijon, France. In 1929, when she was 21. There she began her life-long love affair with France and its food. She was of the same generation as Julia Child. Julia focused on perfecting French recipes and about making those recipes accessible to American home cooks. The subject of Fisher’s writing was ostensibly food, but she was just as interested in the people who prepared the food and those who ate it. She wrote about regional specialities and what a particular food meant to a particular place. And what that food in that place meant to her.

Figure 2. M.F. K. Fisher, A Considerable Town (Marseille)

For some reason, she visited Marseille her first year in France. “(S)ince then,” she wrote, “I have returned even oftener than seems reasonable. The place haunts me.” She called the city and its inhabitants, insolite,“indefinable.” Fisher didn’t set out to write a guidebook. "I am not meant to tell anyone where to go in Marseille(.) All I can do … is to write something about the town itself, through my own senses.” She wrote about the smell of the sea, the intensity of the light, the saltiness of the food and the dryness of the rosé wines. And she wrote about how her proper school girl French deteriorated as she spoke with people whose accents were Italian, Tunisian and Greek. Fisher wrote about the daily fish market which still does business on the Quai des Belges. The day's catch sold by the people who caught it. I watched fish being gutted and sold right off the boats. (Figure 3) Tossed guts all around them. Enough to turn a pescatarian into a vegetarian. And those guts attracted seagulls, so many seagulls. Not my favorite bird. Actually my least favorite bird. Did you know that they poop while flying. Not even pigeons dare do that!

Figure 3. One of the MANY places to buy fish on the quay at Marseille

Along with the fish mongers, there were stands and kiosks selling Savon de Marseille (based on the price, they might have been made in China) and a variety of Marseille sweets. And hats. The sun was so intense, I had to buy one. (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Me and my hat purchased at Le Vieux Port

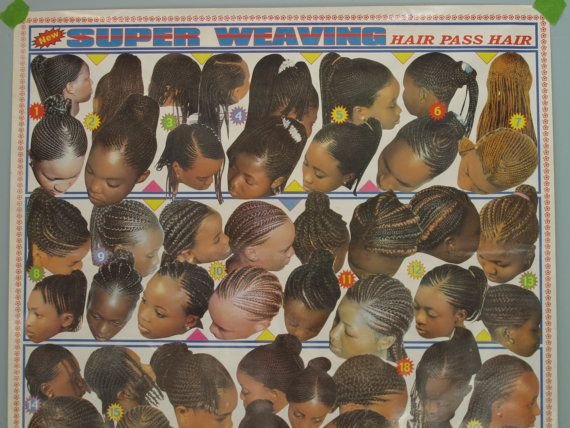

M.F.K. Fisher had especially liked the patterns of the dresses worn by the African women she saw. As I wandered around the port, it wasn’t African textiles that drew my attention. Although I love them. What struck me was something quite different, although related. Women sitting along the Canebière and at the port with posters propped up beside them. (Figure 5) On which are depicted traditional African braided hairstyles. I wrote about those braids in a review of an exhibition curated by Omar Viktor Diop, Patterned Perfection. One of the photographers whose work was highlighted had catalogued the various braid styles and where they came from. (Figure 6) I was so surprised and delighted to see these women. And I am still kicking myself for not having had my hair braided.

Figure 5. Poster advertising various braid styles

Figure 6. Nigerian Hairstyles documented by J.D. Okhai Ojeikere, 1975

The Marseille that I visited last month, a few years shy of a century after M.F.K. Fisher first visited and 50 years after Popeye Doyle did, is not the same place that either of them knew. The City got a face lift when the European Union named it a European Capital of Culture in 2013. It was a designation created in 1985 by Mélina Mercouri and Jack Lang, ministers of culture for Greece and France respectively, It was meant to bring the people of Europe closer together by celebrating the key role played by cities in European culture. In 2013, it was under-appreciated Marseille’s turn.

The esplanade I enjoyed had been refurbished. Among other things, the City enlarged and cleaned up the port. They hired the British architect Norman Foster, (you probably know his Gherkin Building, Millennium Bridge and British Museum addition in London) to make some magic. The result is Ombrière, (Figures 7, 8) a sleek pavilion made of a glistening sheet of steel, suspended by eight slender poles, reflecting everything beneath it. It was disconcerting, but fun, to walk under it and stare up at it. To see people from an angle that you normally don’t see them, to see yourself from that angle. It reminded me of the Bean in Millennium Park, Chicago, (Figure 9) the reflective sculptural arch designed by Indian-British sculptor, Anish Kapoor. Both offer an unexpected pleasure.

Figure 7. Ombrière, Le Vieux Port, Marseille, Norman Foster, 2013

Figure 8. Me underneath Ombrière, Le Vieux Port, Marseille

Figure 9. Bean, Millenium Park, Chicago, Anish Kapoor, 2006

As we wandered around the port, we saw ferries going to several destinations, among them the Château d’If, (Figure 10) a fortress and former prison on the Île d'If, a tiny island about 1.5 kilometers from Marseille. The Chateau was built as an escape-proof prison, the Alcatraz of the Mediterranean. Alexandre Dumas's The Count of Monte Cristo made it famous. The main character, Edmond Dantés, escaped from it after 14 years of incarceration. Actually, no one has ever escaped from it and survived. Apparently at the Château, there is a dungeon dedicated to Dantès. Since I live near a town in the Dordogne, where there are statues of somebody, made famous by a play, who was never actually there, Cyrano de Bergerac, I decided to give it a pass.

Figure 10. Chateau d’If on Ice d’If, from ferry, Marseille

There was another ferry whose destination was Estaque, where I definitely did want to go. And why is that? Well, art history, of course! When we were in Aix-en-Provence the day before we went to the Cote d’Azur, we saw an exhibition on the artist Raoul Dufy. An exhibition that will be coming to Paris in the fall and which I will tell you about then. I noticed that some of the paintings were of Estaque. (Figure 11) Which name was familiar to me, although I had no idea where it was. And when I learned that it was a suburb of Marseille, I stored that info away and hoped to get there when we got to Marseille. How fun to unexpectedly find out that it accessible by ferry.

Figure 11. Terrace at l’Estaque, Raou Dufy, 1908

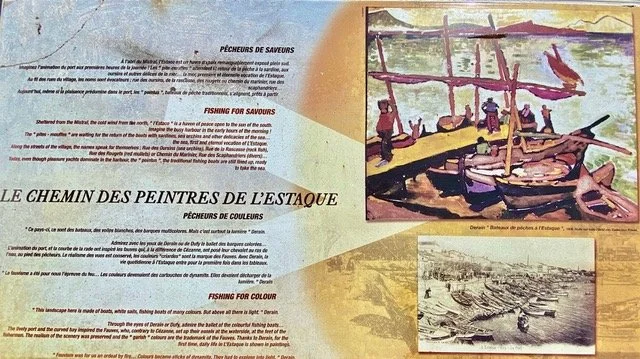

The ferry ride took 30 minutes, it cost 5 euros. It was fabulous. (Figures 12, 13) The Mediterranean Sea is so gorgeous. The sky is so blue. We passed by cliffs and the Chateau d’If; one fortress and then another. When we got to Estaque, there were plaques directing us along the Chemin des Peintres. (Figure 14) I have come upon these plaques in Arles (for Van Gogh) and Pontoise, (for Pissarro). They have reproductions of the paintings at the approximate site they were painted. Very convenient, very useful.

Figure 12. En route to l’Estoque

Figure 13. En route to l’Estaque

Figure 14. Le Chemin Des Peintres de L’Estaque

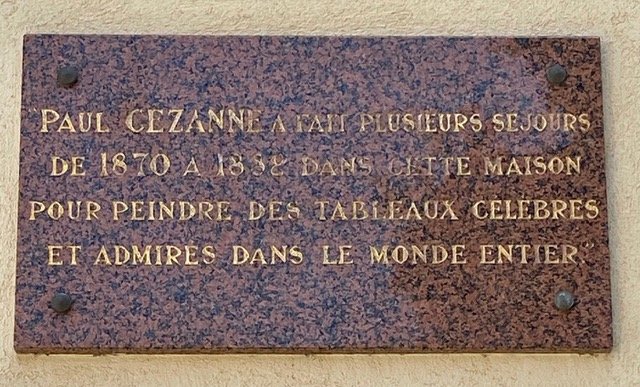

Cézanne (whose muse was usually Mont Sainte-Victoire in his hometown Aix-en-Provence) began visiting Estaque with his family when he was a child. He returned as an adult, as an artist, on and off for 15 years. Signs made finding the house where he stayed in Estaque very easy. (Figure 15) In the 1870s, he painted his first seascapes at Estaque. He divided his compositions into four distinct areas: the shoreline, the heaviest and most thickly painted part; the smooth surface of the water, the mountain range and finally the thin strip of sky. (Figure 16).

Figure 15. Finding Cezanne in l’Estaque

Figure 16. From l’Estaque, Ile d’If in the distance, Paul Cezannem 1885

At the beginning of the 20th century, Raoul Dufy and Georges Braque set up their easels on the shores at L’Estaque. Before Braque arrived, Dufy’s paintings were mostly filled with decorative motifs, like balusters, foliage and vases. (Figure 11, above) Under Braque’s influence, (Figure 17) Dufy adopted a more structured and geometric style, a more cubist style. (Figure 18) Dufy’s five months at Estaque were filled with experimentation.

Figure 17. Houses in Estaque, Georges Braque, 1908

Figure 18. Trees at Estaque, Raoul Dufy, 1908

As we wandered down to the port and the ferry ride back to Marseille, we bought some panisses, Estaque’s chickpea specialty - fritters. (Figure 19) Not to be mistaken for socca, chickpea pancakes, the specialty of Nice. Both are terrific, especially if you like chickpeas, which I do.

Figure 19. Buying Panisses in Estaque

From the Old Port, we explored the oldest quarter of town called, Le Panier. When Popeye Doyle wandered along the labyrinthine streets there, it was a seedy combination of poverty and prostitutes. (Figure 20) Not anymore. The neighborhood has been gentrified. Brothels and bars have been replaced by soap shops and art galleries. (Figure 21) Some have dubbed it the ‘Montmartre’ of Marseille. There is a museum that I didn’t get to see, called Vielle Charité. Something to look forward to next time I’m in Marseille.

Figure 20. Still from The French Connection, Le Panier, 1971

Figure 21. Le Panier today

But there was one museum that I did want to see MUCEM. Walking there from Le Vieux Port, I kept seeing people holding cones with black ice cream. (Figure 22) A quick google check and I learned that it was black vanilla ice cream. Had to get one. Did. The salted caramel I paired it with, tasted better to me. The cone was the freshest I have ever eaten. And it made the long walk to the museum very pleasant.

Figure 22. Glacier vanille noire, Marseille

The focus of MUCEM ( Musée des Civilisations de l'Europe et de la Méditerranée) is European and Mediterranean civilizations. It was completed in 2013, part of the European Capital of Culture Project. The museum is built on reclaimed land at the entrance to the harbor, next to the site of the 17th-century Fort Saint-Jean. The two sites are linked by an elevated footbridge. (Figure 23) The museum was designed by the flamboyant Algerian born Italian architect who grew up in France, Rudy Ricciotti. According to an article about Ricciotti, in the New York Times (2012), he abhors minimalism and supports the “demuseumification of museums.". Both sentiments I can get behind. In 2015, the museum won the Council of Europe Museum Prize. That same year, the French Court of Auditors reported that the final cost of the museum was more than double the original estimate - €350 million rather than €160 million.

Figure 23. Walkway from MUCEM

The museum is a huge cube surrounded by a latticework shell of fiber-reinforced concrete. (Figures 24, 25) It was fun to be under that latticework. There was the same sense of interplay of blue sky and blue sea that I experienced under Norman Foster’s canopy at Le Vieux Port. And it makes sense. Celebrate your best features (within reason, of course!)

Figure 24. Laticework shell of MUCEM, Marseille

Figure 25. Me and the Latticework shell and the beautiful blue sea and sky beyond

The permanent collection traces historical and cultural cross-fertilization in the Mediterranean basin. I can give you sense impressions but they should in no way be considered directions. Along one corridor that I stumbled upon, there was a series of doors that opened into rooms that were screening videos of different epochs in the history of the region. The ones I watched were well done and very interesting.

When I was there, there was a temporary exhibition about Abd el-Kader, who I didn’t know but who was very popular with all the people standing in line to get into the exhibition. (Sunday, Free day, best to avoid if you can, I couldn’t) Just in case you don’t know him either, Abd el-Kader (Figure 26) expected to live the life of an Islamic scholar and Sufi. He never expected to become a military leader. And then he was. He led the struggle against the French colonial invasion in the early 19th century. Fighting a guerrilla war with Algerian tribesmen against a sophisticated French army. In the West he is appreciated for having thwarted a massacre of Christians in Damascus in 1860. In Algeria, he is celebrated for united the country against the French. His ability to combine religious and political authority led him to be called the "Saint among the Princes, the Prince among the Saints”.

Figure 26. Portrait de l'émir Abdelkader, Jean Baptiste-Ange Tissier, 1852.

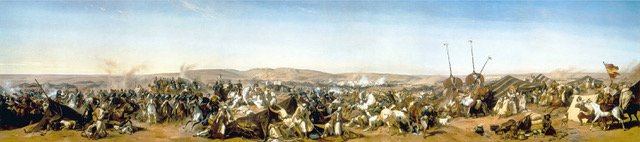

The exhibition was lively, filled with costumes, maps, paintings, prints and books all telling the story of the Emir’s life and accomplishments. Most fabulous of all, was a reproduction of an 1845 painting by Horace Vernet, ‘Capture of Abd el-Kader’s Smalah (encampment) by the Duke of Aumale at Taguin, 1843’. (Figure 27) This panoramic painting is the largest surviving painting of the 19th century. It includes more than 100 figures, many of them identifiable. There are French soldiers on horseback and on foot. There are Emir Abd-el-Kader’s troops, organized in a circle of defense around the encampment (smala). Figures 28, 29). The best part about the display in the exhibition is that by spotlighting certain areas, with commentary, the battle is traced over time and space, with figures identified and actions described. It was like those fascinating deconstructions / reconstructions of paintings that the art section of the New York Times sometimes presents. An exhibition I wasn’t planning to see about someone I knew nothing about and which turned out to be both entertaining and informative.

Figure 27. Capture of And el-Kader’s Smalah by the Duke of Aumale at Taguin 1843, Horace Vernet, 1845

Figure 28. Detail of above (#27)

Figure 29. Detail of above (#27)

I have considered the fact that I had not visited Marseille as a lacunae. Not because I have seen every other part of France, alas, far from it. But thanks to Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher, it has long beckoned me. And now I can’t wait to go back.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.