You can never be too rich: Certainly not on the Côte d'Azur

Today we’re back on the Côte d’Azur, to talk about two homes which are now museums. Very different homes owned by very different people. To visit them, I needed a car. In the past, I rented cars through a company based in Portland, Maine called Kemwel. Their rates were always very competitive. Until Covid.

That’s how I found Free2Move. Prices are less than half their competitors. But, yes, there’s a catch. The pick up/drop off points are not at airports or train stations or city centers. From the train station in Marseille to the pick-up point cost 25 euros. To a car dealership supplying cars to Free2Move as a side gig. When I arrived, it was clear that all was not well. So many people. So few cars. If I had been at an airport or a train station, I would have gone to other agencies to find a car. But I was stuck out in the middle of nowhere. Well, not exactly nowhere because Le Corbusier’s L’unité d’habitation was right next door - very exciting normally but pretty useless at the time. (Figure 1) Somehow we did get a car - although not the one I booked. Smaller which was okay. Manual which was not okay. Because the roads of the arrière-pays are mostly one lane and hair-pin. Free2Move. Time (and trauma) vs Money. Your call.

Figure 1. L'unité d’habitation, Le Corbusier, Marseille, France, 1945 - 52

One day, in that car, I visited those two houses. The first, I learned about last year when I was at the Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild on Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. (Figure 2) Story goes that Baroness Beatrice de Rothschild and her gambling husband (who her family forced her to divorce before he squandered all of her money) visited her husband’s cousin, Théodore Reinach, at his villa in Beaulieu-sur-Mer, just outside of Nice. The Baroness fell in love with the location and bought a parcel of land nearby for her luxurious Venetian style villa/palazzo.

Figure 2. Villa Ephrussi de Rothschild, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, 1907-12

Théodore Reinach’s aesthetic for his Villa Kerylos was decidedly not Venetian, nor was it French. It was Greek. Ancient Greek. (Figure 3) Théodore Reinach was one of three brothers who would make any mother proud. The oldest brother, Joseph was a politician and historian. He was Premier Léon Gambett’s Chief of Staff. But when he joined the call for a new trial for Captain Dreyfus, (the Jewish military officer wrongly accused of treason and sentenced to life on Devil’s Island), Reinach lost his seat in the 1898 elections and was dismissed from his position as a reserve captain in the army. When Dreyfus was exonerated, Reinach was reelected and reinstated. During the Dreyfus drama, Reinach wrote about Raphael Levy, a French Jew, who, in 1670, was burned at the stake for murdering a Christian child. Even though he had an alibi. Even though when tortured, he neither confessed nor converted. Did Reinach write about that earlier moment to give current events an historical context? Maybe. After Dreyfus was exonerated, Joseph Reinach wrote a seven-volume history of the Dreyfus Affair.

Figure 3. Villa Kerylos, Beaulieu-sur-Mer, 1902-08

Joseph’s younger brother, Solomon was an archeologist, philologist and historian. He wrote about French archaeology and Gallic civilization; the history of art and the history of religion. He considered both Judaism and Christianity ‘barbaric’. But, like his brother, he was a committed Dreyfusard. During the Dreyfus drama, Solomon publish a French translation of H.C. Lea’s History of the Inquisition. Perhaps he too wished to establish a context for (then) current events.

Théodore, the youngest brother was also a scholar. He taught the history of religion and edited a review on Greek studies. Like his brother Joseph, he wrote about the Dreyfus affair. Rather than a 7 volume opus, he wrote a single volume summary. But Theodore did find something to write about at length. As editor of the 7 volume French translation of the writings of Josephus, the 1st century Jewish-Roman historian and military leader. Which included a description of the Jewish-Roman War of 66-70 C.E. Events which I first learned about studying the Arch of Titus in Rome. (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Arch of Titus, "Spoils of Jerusalem" relief on the inside arch, Rome, 81 C.E.

These brothers were contemporaries of Proust. So, naturally I wanted to know if any of the brothers made an appearance in Proust’s own 7 volume opus. This is what I learned. Letters survive from Proust to Joseph Reinach. Which confirm what we already know, Proust actively participated in the defense of Captain Dreyfus. Scholars suggest that Joseph Reinach was one of Proust’s models for the character of Professor Brichot, “a professor of immense learning who is, nevertheless,” (at least according to Charlus, one of Proust’s central figures), “too focused on his own interests, … as boring as a specialist who can see nothing outside his own subject, as irritating as an initiate who prides himself on the secrets which he possesses and is burning to divulge, as repellent as those people who, whenever their own weaknesses are in question, blossom and expatiate without noticing that they are giving offense…” (proustreader.wordpress) Another piece of the Proust puzzle falls into place.

That’s the oldest brother, but we’re here to discuss the youngest brother, Théodore. A Philhellene, (Grecophile), he decided to recreate a luxurious Greek house for himself and his family at Beaulieu-sur-Mer, on the Côte d’Azur, near Nice. A parcel of land surrounded by the sea on three sides, which he probably learned was available from his friend, Gustave Eiffel, who had a home nearby. The site was perfect, so too was the architect he selected to realize his dream. Emmanuel Pontremoli, a fellow Jew, a fellow genius, who had won the Prix de Rome for Architecture in 1890.

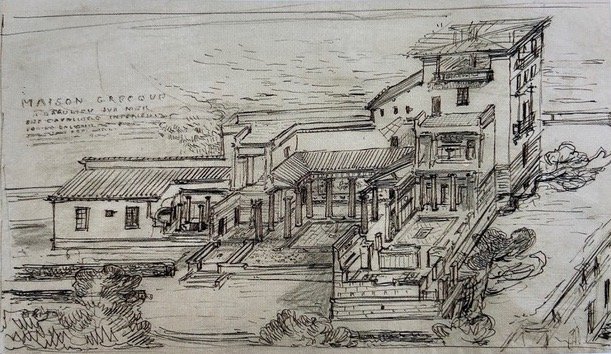

Working together, Reinach and Pontremoli created a modern villa, one an ancient Greek architect would have designed had he lived at the beginning of the 20th century. Many aspects are reminiscent of ancient Greek buildings but many more confirm that this is not a folly, not a play house, but a real house, for real people to live in. (Figures 5, 6) The villa is laid out around an open peristyle courtyard. (Figure 7). And there are openings that permit multiple views of the sea. (Figure 8) Begun in 1902, it was largely completed by 1908. The interior shows Roman, Pompeian and Egyptian influences. There are stucco bas-reliefs, statues and furniture copied from ancient Greek models. (Figures 9, 10, 11) “At every step, the dual requirement of being simultaneously ancient and modern, classical and comfortable, gave rise to a host of original solutions.” The design is “a reflection of the innovations that France showcased at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle.”

Figure 5. Sketch of elevation of Villa Kerylos, 1902

Figure 6. A generation of Reinach children playing outside Kerylos

Figure 7. Villa Kerylos, peristyle

Figure 8. Kerylos exterior, sea views

Figure 9. Marble, statuettes, gold bowl, Kerylos

Figure 10. Mosaic floors, marble walls, furniture based upon Greek models, Kerylos

Figure 11. A la Greque, Kerylos

All the mod coms of the early 20th century are here - from sous sol heating under the decorative mosaic floors to solid marble showers and baths with hot and cold running water. (Figure 12) In the kitchen, history lost, practicality won. This house reminded me of the practical and aesthetic decisions made by Moïse de Camondo when he was building his house in Paris, on Parc Monceau. These two families were to become linked in the following generation, tragically linked.

Figure 12. Marble bath & sink with marble columns and contemporary glass art display, Kerylos

About the name of the house, Kerylos is Greek for king fisher or halcyon, a bird of good tidings, gentle winds, the 'halcyon days' of our past that we remember fondly.

Théodore Reinach died in 1928. A member of the Institut de France, he bequeathed Kerylos to it. His son Léon became the keeper of the archives. But his tenure was cut short when the Nazis seized the Villa and sent Léon, his wife Béatrice de Camondo, and their two children to Auschwitz. Where they were all murdered. Léon had begged his wife to leave France. But she thought that having a brother who died in the Great War, that being the daughter of a man who bequeathed his property and art collection to France, that converting to Catholicism, that having friends in high places, would save her. It did not. Not her, not her husband not her children. After the war, Théodore Reinach’s villa was returned to the family and members lived there or summered until 1967. The Villa is now open to the public. Contemporary artists are invited to display their work here. The exhibition I saw, by two local glass artists, was extraordinary. (Figures 13, 14) Their objets resonated beautifully with the villa.

Figure 13. Glass art by Antoine Pierini, Kerylos

Figure 14. Glass art and copy of Greek statue, Kerylos

Now the second house. Probably the polar opposite of Villa Kerylos. It is the Château de la Napoule, (Figure 15) a restored, well, actually, recreated chateau in Mandelieu-la-Napoule, just south of Antibes. Originally built in the 14th century, this fortress chateau was destroyed and rebuilt over and over again during the next 500 years. And then Henry Clews, Jr. and his wife, Marie. bought it. And moved in with their young son, Mancha. Marie was born Elsie but Henry had a thing for the Virgin Mary, so his Madonna-like wife became Marie. Also, Elsie was his sister’s name. She was a feminist and an intellectual. Henry despised her. Henry and Marie née Elsie went to Paris so that Henry could be an artist with Marie, née Elsie as his muse. Elsie had a new name, Henry wanted one, too. His grandfather had been a potter who made plates illustrating Cervante’s Don Quixote. This is the persona Henry adopted. With Henry as Don Quixote, the Man from La Mancha, of course he named his son Mancha. And insisted that his man servant, renamed Sancha, dress the part.

Figure 15. View of Chateau de la Napoule from the sea

Henry Clews, Jr. was a wealthy American, a very wealthy American. Ditto his wife, Marie, née Elsie. Both were divorced from their first spouses. Henry probably became an artist because he couldn’t do anything else. Certainly not follow in his self made millionaire father’s footsteps and become an investment banker. Certainly not follow in the footsteps of his brilliant older sister, Elsie, who earned a Masters degree and Doctorate from Columbia University, while Henry was failing out of Amherst, Columbia (not easy for a legacy) and finally Leibniz University in Germany.

Henry’s first wife, mother of his two children, divorced him. He wasn’t what she expected. Marie, née Elsie was also married to the wrong person. Who happened to be one of the richest men in Newport, Rhode Island. With whom she had two sons. Elsie was artistic, her friends were artists. Her husband had no patience with her or her friends. He was so miserly that when she sued him for divorce, it was granted.

Henry and Marie, née Elsie married, had a child and left for Paris in 1914. According to Mancha, during the war, Henry and Marie traveled to the U.S. without him. Probably to see Marie’s two sons. As Mancha thought about it, he imagined what might have happened to him if something had happened to them. Which is a reasonable thing to wonder about and the kind of thing that keeps psychiatrists busy. But it wasn’t unique. Babies and infants were left behind when people made long sea voyages. The artist John Singleton Copley and his wife left their newborn in Boston when they sailed with their other three children to London in 1774. One hundred and fifty years later, Lady Rose (yes, I know she’s not real) visited Downton Abbey after she had moved to America. She returned with her husband but without her baby.

In 1917, Mancha contracted the Spanish flu, so he and his parents left Paris for the south of France. They found La Napoule the following year and began to restore it. It would become the focus of their lives. Unlike Théodore Reinach’s Villa Kerylos, Henry and Marie didn’t want a practical home, they wanted a fantasy home. Henry lived for another twenty years, all of them spent at La Napoule. During those two decades, in addition to reconstructing it and embellishing it, painting and sculpting, (Figures 16, 17, 18) they hosted elaborate parties for members of European and American high society.

Figure 16. Cloister with carved capitols, Chateau de la Napoule

Figure 17. Henry Clews Studio, Chateau de la Napoule

Figure 18. Gardens at Chateau de la Napoule, which Marie, née Elsie created

One critic has called what Henry and Marie created at La Napoule “a cross between Disneyland and a Harry Potter film set with Alice in Wonderland thrown in.” At La Napoule, Henry and Marie “lived according to Henry’s strange philosophy which he called humormystics.” Here’s an example. In the tradition of Depictions of Good and Bad Government, (like those by the Lorenzetti brothers in Siena) Henry carved one scene showing the terrible effects of “Gynocracy,” a world ruled by women. Get it, Gyno? And another panel showed the positive effects of a world ruled by men. (Figures 19, 20, 21) Was that was all he could come up with in the aftermath of the Great War. Perhaps it was just a way to tell his feminist sister Elsie exactly what he thought of her.

Figure 19. Door and column capitols carved by Henry Clews at Chateau de la Napoule

Figure 20. Allegory of Good Government, Palazzo Pubblico, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Siena 1330

Figure 21. Allegory of Bd Government, Palazzo Pubblico, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Siena 1330

Well, never mind, he seems to have been madly in love with Marie. Emphasis on the madly. Their entwined initials are carved everywhere. They had a tower built for their tombs. (Figure 22, 23, 24) The tombs face each other and the doors are open, to let their spirits escape. At the top of the tower, completely inaccessible to humans, is a sealed room for their spirits to be together. According to the guide. Okay.

Figure 22. Tower with original sculpture by Henry Clews, Jr. Chateau de la Napoule

Figure 23. Henry Clews tomb, Chateau de la Napoule

Figure 24. Marie née Elsie Clews tomb, Chateau de la Napoule

When Henry died in 1937, Marie stayed at the villa for the next twenty years, until her own death in 1959. Even when German troops occupied it during the war, which required some explaining when the Allies arrived. Again, okay. in 1951 Marie established a foundation, which strives, according to great-granddaughter Natasha Clews Gallaway, who runs it now, to keep La Napoule “a place for artists to reinvent themselves, as Marie and Henry did”.

Figure 25. Gerald & Sara Murphy

We toured La Napoule with a guide (the only way to visit the interior). As she told us about the Clews (she wasn’t a fan of Henry’s, too self indulgent), I couldn’t help but think of another fabulously wealthy American expat couple who lived in Paris and the Côte d’Azur, Sara and Gerald Murphy. They moved to France in 1921 and stayed through the Années Folles. (Figure 25) Gerald was born in Boston into the family that owned the Mark Cross Company. Sara was born into the wealthy Wiborg family of Cincinnati, Ohio. Her father, a chemist, was a self-made millionaire by the age of 40. Sara and Gerald became engaged in 1915 when Sara was 32 and Gerald was 27. They married, had three children and moved to France, dividing their time between Paris and their villa on the Côte d’Azur, called Villa America. They left the U.S. for reasons not unlike the Clews: to escape the strictures of New York and their families' dissatisfaction with their marriage. In Paris, Gerald became a serious painter whose work is still admired. (Figure 26) Sara became a dazzling hostess. Their circle of friends included members of the Lost Generation like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. And artists of Les Années Folles like Fernand Léger and Pablo Picasso - who painted Sara several times. (Figures 27, 28). The Clews’ guest list included the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and the last crown prince of Austria-Hungary. Henry Clews wanted freedom of expression, but only for himself. The Murphys were free spirits who embraced the opportunities and people they found in France. I first read about the Murphys in Amanda Vaill’s book, Everybody was so Young. I left La Napoule thinking that even people whose choices I don’t admire, can inspire reflection, as the Clews did for me. If you are looking for another reason to visit, the views are incredible (Figure 29).

Figure 26. Watch, Gerald Murphy, 1925

Figure 27. Sara Murphy, Pablo Picasso, 1923

Figure 28. Sara Murphy, Pablo Picasso, 1923

Figure 29. One of the many breathtaking views from Chateau de la Napoule

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.