Let’s be objective

Le Nouvelle Objectivité: Centre Pompidou

I saw an exhibition the Centre Pompidou a couple weeks ago. Called Allemagne Années 1920s / Nouvelle Objectivité / August Sander. If you think it’s a mouthful to say (or read), then wait until you get to the exhibition (until September 5).

The exhibition reminded me of a book I read when I was quite young, which made a very strong impression on me. The Once and Future King by T.H. White (or maybe it was the Sword and the Stone, same author, same subject). About the boy who doesn’t know that he will pull the sword out of the stone. That he will become King Arthur. The magician Merlyn does know Arthur’s destiny and prepares him for it by transforming the boy into a variety of animals. Each to instill a lesson. In one transformation, Arthur becomes a bee. At first Arthur feasts on the nectar and the pollen. He doesn’t want to take the pollen back to the hive. But gradually he tires of the taste and it becomes just a job. I took that lesson to heart and I have applied it literally ever since. As soon as whatever I am eating no longer tastes great, I just stop eating it. Luckily, I love leftovers.

Why did I bring this up? Not to tell you about my personal eating habits. But to explain that for me, visiting a temporary exhibition at the Pompidou is very much like being a bee. At first, everything is really interesting and I am eager to move into the next space, onto the next subject. But gradually it becomes, not less interesting, because it is still interesting, but somehow less meaningful. I have to sit down. I have to go to the toilet. I have to get out of there. And so, I just throw in the towel, or the napkin (if we’re sticking to the Arthur and Merlyn and my eating habits analogy) or in this case the gallery guide. And decide to come back another day. Which I did. I love leftovers.

But still, the Pompidou is a puzzlement. Why do exhibitions there have to be so exhaustive and exhausting. I am remembering, for example, the exhibition called ‘Women in Abstraction’ which drove me to distraction. Because it simply would not end. Like the current exhibition. I find it particularly curious that the curators at a modern art museum choose not to follow Mies van der Rohe’s dictum, ‘less is more’. The essence rather than the overstatement. The exhibition philosophy at the Pompidou seems to be ‘more is more’. Everything but the kitchen sink. No, wait, the kitchen sink too. In brief, this exhibition is not the Cliff Notes version of artistic and cultural trends in Germany during the 1920s, make that 1925-1929.

Whew, okay, maybe we should talk about the exhibition now. Museums, like every other institution, love centennials, so it makes sense that the Pompidou decided to look at what was happening in Germany in the 1920s. The decade was the focus of an exhibition on the Japanese artist Foujita in Paris at the Musée Maillot a few years ago. And the exhibition last year on Jewish artists in Paris at the MahJ. Pionnières, which is still on at the Musée Luxembourg, is about women artists of the 1920s.

In France, the 1920s is called Les Années Folles. In the United States and England, the decade is called The Roaring Twenties. In all three countries there was a general ‘party like there’s no tomorrow’ vibe. Which in retrospect was probably a good idea since tomorrow came all too soon. Of course it was a sensibility easier to adopt if your country came out victorious after a brutal war, even if it was followed by a cataclysmic pandemic. Which was not the case with Germany. Obviously. They had the war and the pandemic. But not the victory. It does change how you look at things. Everything. As one critic put it, ‘chloroformed by the defeat of 1918, the fall of the Empire and its colonies, the hyperinflation of 1923, the mass unemployment which followed and soon by the world crisis of 1929, Germany advanced staggeringly towards the triumph of Nazism in 1933.” All the charged words left me breathless- chloroformed, staggeringly, defeat, hyperinflation, triumph of Nazism. As we move toward our own abyss, I wonder what words will be used to describe our path 100 years from now, if there is a 100 years from now.

Right, the exhibition at the Pompidou. What was the Nouvelle Objectivitié, New Objectivity, or actually, “Neue Sachlichkeit” all about. Just like every other art movement in history, started out as a reaction against the style that preceded it. In this case, against German Expressionism. That art movement, which began at the beginning of the 20th century, is characterized by a focus on emotions and feelings. And of course, it was a reaction against what had preceded it, art that focused on nature and reality.

Expressionism was all about expressing the personal. New Objectivity was all about suppressing the individual. The point was not philosophical objectivity but practical engagement. As themes in painting, literature and music. As solutions in architecture and design. The Weimar Republic promoted a culture that focussed on the masses.The cult of the individual was replaced by a celebration of standardization. The New Objectivity favored collaboration and engagement. And the implications were these. With standardization came the notions of rationality and utility. Art forms, including painting, music, literature and theater (Figure 1) were conceived for a wide audience. With themes and subjects anchored in their time and designed to be understandable. In city planning, the unprecedented shortage of housing at the end of World War I led to the construction of large housing blocks (Figure 2) with simple and identical forms, standardized according to principles of rationalization.

Figure 1. Kurt Weil, The Beggars Opera, 1928

Figure 2. Werner Mantz (photographer) Block of homes, Cologne, 1928

And after the war, the focus of the country business. On maximizing productivity and minimizing individuality. It was a philosophy that the Germans understood to be intrinsically American. The rationalization of labor developed by Frederick Taylor (The Principles of Scientific Management, 1911) was adopted by German companies. Industrialization and the mechanization of tasks. (Figures 3, 4)

Figure 3. Assembly line production of vacuum cleaners at the Elektromotorenwerk, Siemens' electric motor plant in Berlin,1930.

Figure 4. Carl Grossberg, Flywheel with Drive Belt, 1930

When we think of mechanization and assembly lines, we think of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, (Figure 5) or maybe I Love Lucy when Lucy and Ethel work at the chocolate factory (fun fact: it was a See’s Chocolates in Los Angeles). (Figure 6) But the reality wasn’t that and it isn’t that now for people whose work is grueling and repetitive and who live with the threat of being replaced by robots.

Figure 5. Charle Chaplin, Modern Times, 1936

Figure 6. Lucy & Ethel, I Love Lucy, Switching Jobs

The exhibition has a video of dancers who look a lot like the Rockettes. (Figure 7) They are the Tiller Girls, a dance group formed in England. They were a hit in Germany in the ‘20s. One journalist called their performances visual expressions of Taylorism, their chorus line a mechanical and simultaneous repetition of identical gestures at identical speed. The individual expression sacrificed, group performance celebrated.

Figure 7. The Tiller Girls are here, 1926

Painters and photographers of the New Objectivity glorified the beauty of machines. Images of men and their radios (Figure 8) and a prototype of the iconic black telephone (Figure 9) make their appearance in this exhibition. As architects were creating massive housing blocks in response to the acute housing shortage after the war, designers were concentrating on the interior layout of small dwellings to optimize space. A model kitchen is in the exhibition. (Figure 10) It was designed by a woman architect, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky who gave it a Taylor vibe. Using scientific data to analyze the usual movements of housewives, she organized the space to minimize time and maximize efficiency. The worktop was next to the sink, tasks could be performed seated. It would take another war and another 25 years before Charlotte Perriand and Le Corbusier joined forces at the Unité d'Habitation of Marseille. In 1947, Perriand sketched a model kitchen for Corbu’s answer to that period’s housing shortage.(Figure 11)

Figure 8. Max Radler, Man building radio, 1920s

Figure 9. Richard Schadewell & Marcel Breuer, designers, Telephone, 1929

Figure 10. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Frankfurt Housing Kitchen, 1926

Figure 11. Charlotte Perriand, Model Kitchen, Marseille, 1947

Marcel Breuer designed his iconic stacking tables (Figure 12) in 1925 for the Bauhaus. A design school which has always seemed so extreme to me. But in the context of what else was happening in Weimar Germany during the 1920s, it seems downright enlightened.

Figure 12. Marcel Breuer, Stacked (nesting) Tables, 1925

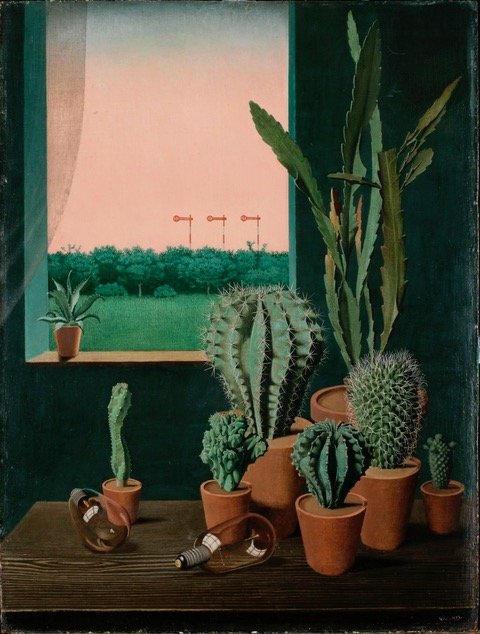

And for some reason, artists were fixated on things. There are lots of paintings in this exhibition of things. Marie Kondo would have her work cut out, ditto a psychiatrist. Still life paintings of living things (mostly cacti which at that time and in that place was considered exotic) (Figures 13, 14) and man made things, not artisanal but industrial. Usually in identical multiples. How else to show that they were made by machine.

13. Georg Scholz, Cacti and Semaphore 1923

Figure 14. Albert Renger-Patzsch, Flat Irons for Shoe Manufacture, 1928

And then there were paintings of Cool Guys, what the exhibition calls ‘Cool Persona’. According to literary historian Helmut Lethen, the humiliation suffered by Germany at the end of the First World War gave rise to a culture of shame in Germany. To combat it, these men (and women, too) presented themselves as indifferent, detached. What counted was not their inner thoughts but the outer manifestation of their place in society as defined by their occupations. These cool types abound in paintings and photographs, sometimes of the same person. (Figures 15, 16, 17)

Figure 15. Anton Räderscheádt, Young Man with Yellow Gloves, 1921

Figure 16. August Sander, portrait of Anton Räderscheidt, 1926

Figure 17. Christian Schad, Portrait of Dr. Haustein, 1928

And what about women, I hear you asking. Well, when the men went to war, the women went to work. This redefinition of traditional gender roles was a subject that both painters and photographers explored. And although women were often forced to abandon the jobs they had performed so successfully during the war (at lower pay, it seems unnecessary to add) when the men who came back, took back their jobs, German women did get the vote in 1918 (the same year as England, 2 years before the 19th amendment in the United States and nearly 25 years before women got the right to vote in France).

If they were going to do a man’s job, some women reckoned, they might as well dress the part. So loose shirts replaced corseted bodices, short hair replaced chignons. (Figures 18, 19, 20) The androgynous look wasn’t unique to German women in the 1920s, of course. France had its garconnes who dressed like boys. In America, flappers dresses had low waistlines and short skirts. And none of these women hesitated to smoke and drink in public and dance in jazz clubs. All documented by the artists and photographers of the day. And then there were the women and men who pushed boundaries of gender. For them, there were the famous Eldorado cabarets which offered drag shows and performances by transvestites. They attracted lesbians, gays and transgenders, as well as artists, authors and audiences of more heterosexual tastes. More tourists than transgressors. The club and its clients have been immortalized by painters and photographers. (Figures 21, 22, 23)

Figure 18. August Sander. Secretary at West German Radio, Cologne, 1931

Figure 19. Otto Dix, portrait of Sylvia von Harden, Journalist, 1926

Figure 20. August Sander, Helene Abelen, painter’s wife, 1926-27

Figure 21. Kate Diehn-Bitt, self portrait, 1935

Figure 22. Otto Dix, Portrait of Karl Krall, jeweler, 1923

Figure 23. Otto Dix, Portrait of cabaret dancer, Anita Berber

The exhibition includes examples of drawings and prints by artists who felt threatened by all this gender fluidity. Their work, called Lustmörder (sexual crimes) are nightmarish. Cautionary tales of what happens to women who seek emancipation and sexual freedom. Depictions of women slashed and hanged. (Figure 24) So, while these guys were working through their anxieties, they were certainly causing them in others.

Figure 24. Karl Hubbuch, Der Lustmord (sexual murders) 1930

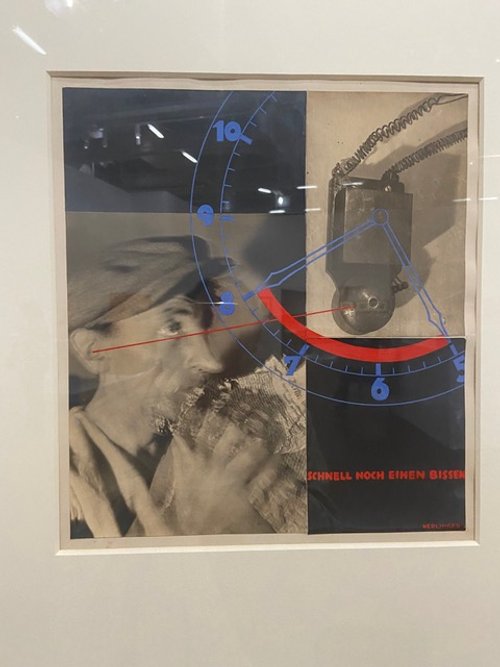

From 1924, until the 1929 crash when American investors called in their German loans, American capital brought relative economic stabilization. Of course, not everybody benefited. Especially the laborers and beggars depicted by artists who were members of the Communist Party. Their subject was the drudgery of daily life for workers, cogs in the wheel of Taylorized machines. The anonymous workers in huge factories that scientific research had created to maximize efficiency. These workers may have contributed to the wealth of the factory owners, but they didn’t share it. (Figure 25) And yet, Hans Baluschek’s Summer Evening reminds me of a photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson of French workers enjoying a bit of leisure. (Figures 26, 27).

Figure 25. Oskar & Alice Lex-Nerlinger, Schnell, noch einen Bissen, 1928. Quick, one more bite before the 15 minute lunch break is over & time to return to work.

Figure 26. Hans Baluschek, Summer’s Evening, 1928

Figure 27. Henri Cartier-Bresson, On the Banks of the Marne, 1938

Oh wait, I forgot to tell you that this exhibition has a Part 2. Seriously, not kidding. Along with this exhaustive look at German art and just about everything else from 1925-1929, it is also an exhibition of one particularly photographer, August Sander. Who, around 1925, began his People of the 20th Century project, a system of categorizing and classifying German society. He started with farmers and craftsmen and then moved on to documenting the different social classes and professions in the countryside. Next was the City. Which, for Sander, was a model of both progress and decline. One group of portraits was of marginal populations, travelers and gypsies, the unemployed, the destitute, the beggars. (Figures 28, 29) His photographs are both types and individuals. Types because his intention was to photograph representatives of certain professions and classes. Individuals because, by asking people to pose for him, he couldn’t help but show them as individuals. He stopped working when Hitler came to power and his son was arrested. After the war, he began a project he never completed - documenting the perps and victims of Nazism.

Figure 28. August Sander, Vagrants, 1929

Figure 29. August Sander, Beggar 1930

Yes, the exhibition was too long. Yes, there was too much stuff. But the dizzying array of presentations kept it lively. Paintings and photographs. Furniture and architecture. Videos and costumes. Remember to leave while it still looks good and come back when you’re hungry for more.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.