Giovanni Boldini: The Master of Swish

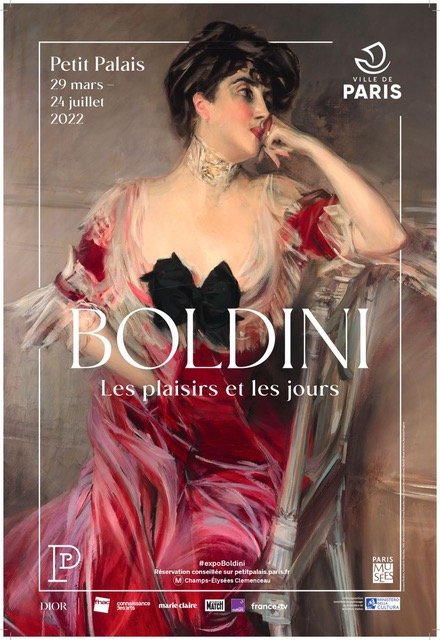

Boldini Pleasures and Days, Petit Palais

Parisiennes and Proust. Dandies and the Demimonde, Boldini and the Belle Époque. And of course, Corsets ! Whew ! That’s quite a list. We better get started. Have you heard of Giovanni Boldini? The Italian portraitist who painted everybody who was anybody and anybody who wanted to be somebody. Mostly gorgeous women dressed in fabulous gowns. The exhibition I am going to tell you about today is not only some glorious paintings but a sprinkling of ethereal gowns and a soupçon of amazing accessories in which these women with the longest of legs and slenderest of waists, posed.

Has Proust always been everywhere or will this constant referencing be over when the 150 anniversary of his birth and the 100 anniversary of his death finally come to an end at the end of this year? The reason I ask is because those of you who are not ‘Proust Heads’ may need a little help with the title of this exhibition. Boldini Les Plaisirs et les Jours (Pleasures and Days). Turns out, it’s Proust. Les Plaisirs et les Jours was a collection of prose poems and novellas published by Proust in 1896. It was his first publication. Either the vacuous ‘pensées’ of a superficial 25 year old boy or harbingers of what would become one of the greatest books ever written. Critics’ opinions vary.

An exhibition that was held three years ago, in Ferrara, in Boldini’s hometown, suggests that Proust is always there, if you know where to look. One critic noted that “walking through the exhibition was as close as a visitor could get to traveling through the pages of À la recherche du temps perdu.” With portraits of the people who inspired some of the main characters of Proust’s novel, among them the Baron de Charlus and the Duchesse de Guermantes, aka Count Robert de Montesquiou and his cousin Élisabeth Greffulhe.

Boldini’s portrait of Count Robert de Montesquiou, (Figure 1) was painted in 1897, a year after Proust’s juvenilia. Montesquiou, twenty years Proust’s senior, was an aristocrat, a poet, an intellectual and an art collector. Oh, and a closeted homosexual and a dandy. In the Proust exhibition that just closed at the Carnavalet, there was a clip from a film adaptation of Proust's opus showing the Baron de Charlus being whipped at a male brothel. He seems startled at first but then he seems to like it. But what do I know? Let’s forget that and concentrate on this portrait in which the Count is completely clothed and totally in control. Dressed in shades of white and black; gray and moss green, his thin torso and narrow, well-barbed face turn left. His legs turn right. And the painting becomes a series of wonderful angles formed by torso, thighs, arms and in one elongated hand, an elegant blue handled wooden cane. A celebration the ‘effete panache of a man whose self-obsession was notorious’.

Figure 1. Count Robert de Monttesquiou, Giovanni Boldini, 1897

A few years later, Montesquiou wrote an article about portraiture in general Boldini’s portraits in particular. He wrote, ”the art of portrait painting lies not in photographic verisimilitude, but in the ability to blend the personality of the painter with that of the model.’ Boldini’s portrait of Montesquiou celebrates him as an aesthete, as a dandy, as Boldini saw him. Holding his cane ‘like a sceptre, transforming it into a symbol of royalty,… illustrating the first verse from a poem in Montesquiou's volume, Chauve Souris: “I am the sovereign of transitory things,” he is as the sitter saw himself.

The art historian, A. R. Willard, writing at the same time, described Boldoni’s genius this way. “The essential quality in his talent is the quality which marks the success of a clever caricaturist – an abnormally acute perception of what gives individuality to a face or figure. (Figure 2) The caricaturist deliberately makes the quality ridiculous… Boldini went as close to the precipice as possible, then stopped, saving ”his own self-respect and that of his sitter.”

Figure 2. Lawrence Alexander Brown, Giovanni Boldini, 1902

Boldini was born in 1842, in Ferrara, Italy. At 20, he left for Florence where he stayed for 6 years, studying painting and painting with a group of artists, the Macchiaioli, so-called Italian precursors of Impressionism. He, like them, painted landscapes. Then he picked up and moved to London where he became a very successful society portrait painter. And then he moved on, again, this time to Paris where he lived from 1872 until his death nearly 60 years later. In Paris, he began by painting genre scenes, (Figure 3) but he quickly moved back to portraiture. His portraits met with the same success as they had in London. From the 1880s until just before the First World War, that is the Belle Époque, he was the society portraitist par excellence. He soon became inseparable from Paul-César Helleu, who was probably Proust’s model for the artist Elster, and whose drypoint of Proust on his deathbed, suggests that theirs was a true friendship. (Figure 4) And the caricaturist, whose nickname was Sem. (Figure 5) And from whom Boldini probably picked up a few tricks of the caricaturist’s trade.

Figure 3. Crossing the Street, Giovanni Boldini, 1873

Figure 4. Proust on his deathbed, Paul César Helleu, 1922

Figure 5. Helleu, Sen and Boldini with Coco Chanel at Deauville, 1912

Boldini’s name is associated with Dandies and Parisiennes of the Belle Epoque. Montesquiou was a dandy and we may as well consult Charles Baudelaire for a definition. We learn that it was not what a man did that made him a dandy, since dandies had "no profession other than elegance... no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons..” The dandy, in short, “must aspire to be sublime …; he must live and sleep before a mirror.” Oscar Wilde, that dandy par excellence, (Figure 6) concurred. He wrote that "One should either be a work of Art, or wear a work of Art.” And of course, as he lay dying in a squalid hotel room in Paris, he reportedly said something like “Either the wall paper goes or I do.” And he did.

Figure 6. Oscar Wilde in New York, 1882

The female equivalent of the Dandy was the Parisienne. Berthe Morisot, a Parisienne herself by both birth and dress, painted a fair share of them. (Figure 7) Throughout the 1870s and 80s, Morisot depicted La Parisienne, as a single figure, dressed in a costume that ranged from a simple white muslin frock to an haute couture gown. Morisot, like her fellow Impressionists, was fascinated both by the latest Paris fashions and fashion magazines which offered suggestions for poses and props.

Figure 7. Before the Theater, Berthe Morisot, 1873

James Tissot tried his hand at painting Les Parisiennes. Without success. Maybe it was because Tissot was hoping to capitalize on a fad after having lived in London as a successful portraitist for many years. His scheme was to paint a series of 15 Parisiennes to be sold as prints. (Figure 8) He depicted elegantly dressed women, some in front of well known Parisian monuments, others shopping, still others attending spectacles. But the paintings were not successful, too English. He had been away too long. What did he know about Parisiennes? His paintings were criticized for brush strokes that were too feathery and women’s bodies that were too elongated. Maybe Tissot was just ahead of his time because those were two attributes for which Boldini’s very successful canvases were singled out.

Figure 8. The Gaze, James Tissot

When we talk about La Parisienne, we must also talk about the demimonde. The world of the courtesan who shared “the attributes of beauty, fashionableness, desirability and wealth” with the wives and daughters of the men who kept them, on the side, as an escape from the responsibilities of their ‘real’ lives as husbands and fathers. In Belle Époque Paris, fashion was no longer the domain of the aristocracy. A courtesan of the demimonde was a fille publique who dressed exactly like a femme honnete. There were some places that a courtesan couldn’t go, of course, like private gatherings, where men’s wives were entertained. But for the most part, courtesans had both beauty and wealth and were as much a part of Parisian public life as the dandy.

The woman depicted in this portrait, (Figure 9) Marthe de Florian called herself an actress, but she was really a courtesan whose lovers included prime ministers and portraitists, one of whom was Boldini who painted this portrait in 1889, when Marthe was 24 years old. When she died, her granddaughter inherited the apartment, which she closed up when she fled Paris in 1942 She never returned. The apartment remained locked, unvisited, for the next 70 years. It was only upon the death of this granddaughter that all of the treasures Marthe de Florian had amassed during her lifetime, were discovered. Amongst them, this previously undocumented portrait of Marthe by Boldini which sold at auction for 2.1 million euros in 2010. It was found surrounded by other Art Nouveau treasures, letters from her famous lovers, a rainbow of ribbons, bottles of unopened perfumes and a figurine of Mickey. (Figures 10, 11)

Figure 9. Marthe de Florian, Giovanni Boldini, 1889

Figure 10. The apartment of Marthe de Florian, Paris

Figure 11. The apartment of Marthe de Florian, Paris - note Mickey Mouse

Boldini was called upon to paint both fashionable wives and fancy mistresses in elegant gowns. And he mostly painted them in his studio. Indeed in a corner of his studio. (Figure 12) Backed up against a door frame or sitting on the edge of a chair or a sofa or a bergère. Their bodies slightly unbalanced, their torsos and legs slightly elongated. Stephen Gundle (Journal of European Studies, September, 1999) writes that Boldini mostly painted his female sitters with bare arms and plunging décolletages, almost in deshabille (undress). “Gowns (writes Gundle) were rendered with 'indefinite slapdash strokes' made to look 'swagged or pinned … haphazardly’ together and sitters’ hairdos seem to have been arranged hastily.” Or maybe coming undone. (Figure 13) Boldoni was a notorious lecher so maybe his sitter’s presentation and comportment was a function of the wrestling match they had just enjoyed/endured with the painter. He was also apparently a very short, very unattractive man. (Figure 14) Perhaps even the Harvey Weinstein of the Belle Époque.

Figure 12. Olivia Concha de Fontecilla, Giovanni Boldini, 1916

Figure 13. Mademoiselle de Demidoff, Giovanni Boldoni, 1908

Figure 14. Self Portrait, Giovanni Boldoni, 1911

Some writers have suggested that Boldini’s rapid, slashing brushstrokes were about something else. About his interest in both speed and electricity. Indeed, in portraits like the one called Fireworks from 1895, (Figures 15, 16) the gown seems to be composed of bolts of lightening or electricity (ask Benjamin Franklin to explain the connection) that remind me of a light bulb. Like the Street Light (Figure 17) the Italian Futurist Giacomo Balla painted 1909.

Figure 15. Fireworks, Giovanni Boldoni, 1890

Figure 16. Marquise Luisa Casati, Giovanni Boldoni

Figure 17. Street Light, Giacomo Balla, 1909

Boldini was, of course, fascinated by fashion. He knew the top designers and he borrowed gowns from them. Gowns in which he sometimes dressed his sitters. So, when we look at a portrait by Boldini, we don’t always know if we are looking at a gown from the sitter’s closet or one from Boldini’s. And in this way, Boldini was exactly like Hyacinth Rigaud whose closets were often much fuller and grander than his sitter’s.

There is a difference between Les Parisiennes of Tissot and Morisot and those of Boldini’s early and later works. I wonder if you have noticed. The earlier sitters all wore corsets. Julia Nolet has a wonderful description of the corset in her monograph on the artist Edouard Vuillard whose mother owned a corset shop. The 19th century corset, Nolet tells us, “combine two things not usually found in a single article of clothing: sexual allure and disciplined respectability. (Figure 18) Although marketed as a health necessity and sometimes used medically as a back support for the disabled, until shortly before the First World War, the corset was above all essential to a fashionable European woman’s wardrobe.” They were both expensive and uncomfortable. They epitomized both vanity and enslavement. Kathe Politt (whose New Yorker essay on learning to drive is not to be missed) writing a decade ago, contended that the corset was a “female exoskeleton capable of propping up, containing and defining a woman’s weak, soft, plump flesh .. artificially narrowing her waist and emphasizing the (roundness) of her bosom and buttocks, while painfully - even injuriously - restraining her body.” (Figure 19)

Figure 18. 19th century corset

Figure 19. A Gibson Girl, the American Equivalent

Les Parisiennes of the 1880s had bodies defined by metal wires and stays that bound them in place. Maybe you couldn’t breathe but you also didn’t have diet or exercise or suck in your gut. All taken care of by your undergarments. But that all changed when a corsetière cut her corset in two, put straps on the top half to support her breasts and tossed out the bottom half. Thus, Nolet tells us, “the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889 introduced two iconic structures: the Eiffel Tower and the world’s first brassière.” And ever since, women have seesawed between girdles and anorexia; Spanx and bulimia.

According to Marthe-Lucile Bibesco who had her portrait painted by Boldini in 1911, ladies of the time “dressed à la Boldini” and underwent slimming treatments in order to “resemble the ideal woman according to the canons of Boldinian beauty.” In Boldini’s portrait of her, (Figure 20) she is seated in a corner, her gown fluttering around her torso and thighs. We feast our eyes on a little ankle and a lot of shoulder. She liked the painting but her husband did not. His verdict: the artist had rendered her “cleavage unseemly”. Okay to depict his mistress that way perhaps, but certainly not his wife!

Figure 20. Marthe-Lucile Bibesco, Giovanni Boldoni, 1911

Boldini was facile and is now largely forgotten. Like Tissot in his heyday, Boldini was a business man as well as a gifted artist. He painted for the present and not for posterity. And yet, it is fun to see these beautiful paintings juxtaposed with the sumptuous gowns his sitters wore. See the exhibition, it will do you a worldly world of good.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.