The Philosophical Prince

À la rencontre du petit prince: Musée des Arts Decoratifs

There’s an exhibition at the Musée des arts decoratifs on through June. I saw it last week. I saw it a few months ago, too. But I didn’t know if I would be able to write about it. Not because the subject doesn’t interest me. It does. Maybe too much. I won’t say it is a ‘litmus test’ exactly, but I will admit that when I am getting to know somebody, I sometimes ask them what they remember most about Le Petit Prince. Does their answer matter? It does to me.

So, I was looking forward to learning about the short life and long reach of the author of Le Petit Prince. Because, (and I’m speculating here), to keep my pleasure pure and my attention focused entirely on the Little Prince, I have resisted learning too much about Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. I came to this exhibition hoping it would fill that lacunae. Which it did. I learned a lot and although some of what I learned was alarming, more of it was endearing, even enlightening. And I still love the book, maybe even more. Whew!

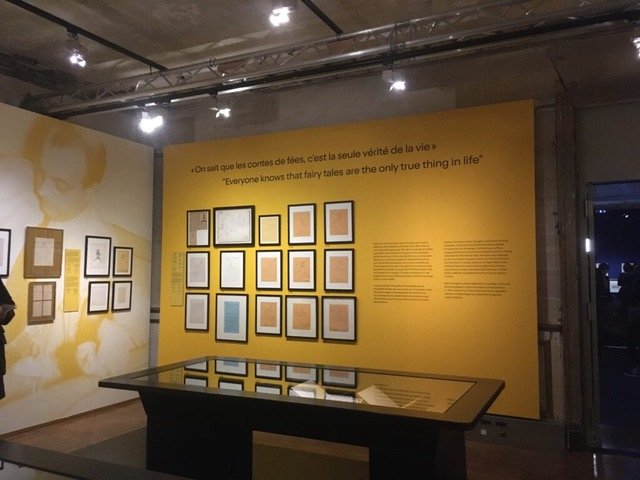

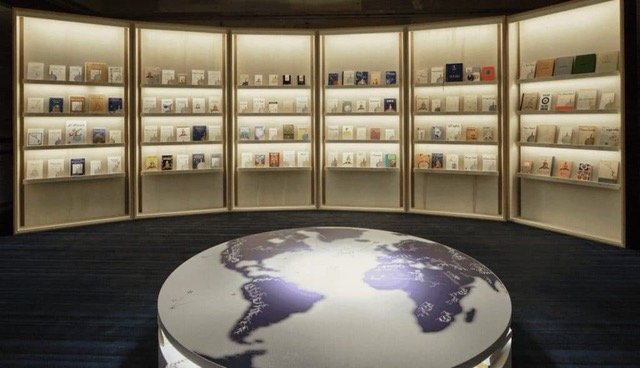

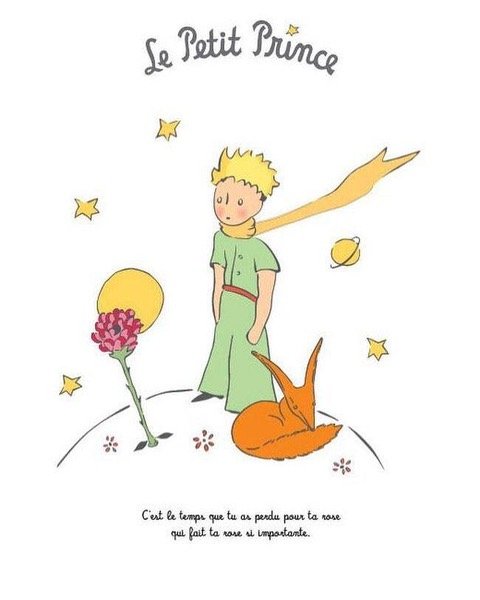

The exhibition unfolds like a voyage, along a not always obvious path, towards a destination you know but which you might not have predicted. Twinkling stars sometimes fill a night time sky,(Figure 1) film clips and photos, costumes and a cut-out of the prince where little princes and princesses can pose for their picture, help tell the story. (Figure 2) Quotations on the walls bring Le Petit Prince to life. (Figure 3) In the room near the end, handwritten pages of manuscripts and hand drawn illustrations abound. (Figure 4) They let us trace how the story took form, how ideas and characters were tried and then abandoned along the way. As the author refined his tale and selected which characters he wanted to tell it. But while this room may have been our goal, it isn’t the end of the exhibition or the story. Because Saint-Ex (as his friends called him) slid into the cockpit again. To fight for France. The photos of his last few months as a pilot, before his plane went down, fill the penultimate room. (Figure 5) The exhibition’s end is upbeat. A room with copies of Le Petit Prince in many different languages, a celebration of its universal, enduring appeal. (Figure 6)

Figure 1. Petit Prince exhibition, Musée des arts decoratifs

Figure 2. Petit Prince exhibition, Musée des arts decoratifs

Figure 3. Petit Prince exhibition, Musée des arts decoratifs

Figure 4. Petit Prince exhibition, Musée des arts decoratifs

Figure 5. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry as pilot

Figure 6. Petit Prince exhibition, Musée des arts decoratifs

So, who was Antoine de Saint-Exupéry? He was born in 1900 into two ancient, impoverished aristocratic families. By ancient, I mean dating back at least to the 13th century. By impoverished I mean that his father had to find a job, which he did, selling insurance. Antoine’s mother was 12 years her husband’s junior. After 8 years of marriage, they had 5 children. After 8 years of marriage, Antoine’s father dropped dead of a stroke. He was 41 years old. Antoine was not yet 4. Forced to leave their home, the fatherless family moved first into the chateau owned by Antoine’s mother’s parents. That arrangement lasted for only 3 years, coming to an end when Antoine’s grandfather died. They moved next to a chateau owned by one of Antoine’s mother’s aunts. It was in this chateau and its surrounding park, Saint-Expéry’s biographer Stacy Schiff tells us, that Antoine created what he described as “the secret kingdom” of his childhood, his “interior world of roses and fairies,” where he and his siblings were indulged by their gentle, loving mother. It was here, too, before he left for boarding school at age 10, that Antoine began writing poetry, mainly at night. And not thinking twice about waking his siblings and mother to hear what he had just written. For Saint-Ex “childhood was a lost golden age, its haunting memory both a blessing and a curse.” (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Saint-Exupéry children (Antoine second from right)

His childhood was also filled with a lot of well meaning adults who wanted to help his indulgent mother raise her brood. Schiff tells us that “the adult relatives of the Saint-Exupéry children regarded them as horribly spoiled, and intermittently did their best to impose the discipline that their mother never could.” When he finally got his chance, he got his revenge.

“I have lived a great deal among grown-ups, I have seen them up close. That has not much improved my opinion.” (Le Petit Prince)

The grown-ups Saint-Ex scorned did not include his mother, of course. (Figure 8) Antoine was a mama’s boy, from his earliest years until the end of his life. He began writing his dear Maman letters when he first went off to boarding school at age 10 and continued writing to her until 1944, the year he died. His dear Maman outlived him by almost 30 years. As a mother, I find that almost unbearable to imagine. One critic, reviewing Stacy Schiff’s biography, writes that Saint-Ex’s mother represented ‘security, refuge and childhood nostalgia.’ Schiiff puts it this way, Saint-Ex “wore this fierce maternal love as a sort of cloak wherever he went, pulling it more closely around himself as he aged.” He wrote, “This world of childhood memories will always seem to me hopelessly more real than the other.”

Figure 8. A book of 100 letters that Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote to his mother

In one of the first letters Antoine wrote to his Maman, from boarding school, he tells her how much he misses her and and his sisters and brother. How he wishes to be with them, to take care of them. One critic suggests that Saint-Ex’s devotion to his mother, to his childhood memories, makes him a “member of that gruesome tribe—the Boys Who Never Grow Up”.

But as I read Antoine’s letter, I was not reminded of Peter Pan. It was the March family that came to my mind. The tender times the March sisters shared with Marmee when Dr. March was away during the Civil War. They too were the ‘poor relations’ who had to depend upon themselves and each other for merriment and comfort, who had to put up with wealthier relatives telling them what to do and how to behave. Le Petit Prince might have been Saint-Ex’s way to find that place again. “We are of our childhood as we are from a country”

At 17, when he was at boarding school, tragedy found his family again. His brother François, with him at school in Switzerland, died of rheumatic fever. When his father died, he became the oldest male in his family. With his brother’s death, he became the only male. Some suggest that François may have been Saint-Ex’s inspiration for the little prince. Saint-Ex’s doodles often included a little person like his little prince. (Figure 9) Maybe those doodles started as early as the death of his beloved brother.

Figure 9. Saint-Exupéry’s watercolor drawing of Le Petit Prince, 1942, onion skin paper

After school, Saint-Ex faltered, trying to find his place in the world. (Figure 10) But that changed in 1921, when he began his military service and began taking flying lessons. He had found his passion. He transferred out of the French Army and into the French Air Force. And that’s also when he began crashing planes. Which he did with some regularity. Throughout his career. Causing irreversible damage to himself and usually to his planes. In 1926, he left the Air Force, and became one of the pioneers in international postal flight. He worked for Aéropostale flying between Toulouse and Dakar and then as the stopover manager for the Cape Juby airfield in the Spanish zone of South Morocco in the Sahara desert. His responsibilities included negotiating the release of downed fliers taken hostage by Saharan tribes. Three years later, he was transferred to Argentina and became the director of Aeroposta Argentina airlines.

Figure 10. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry as young man

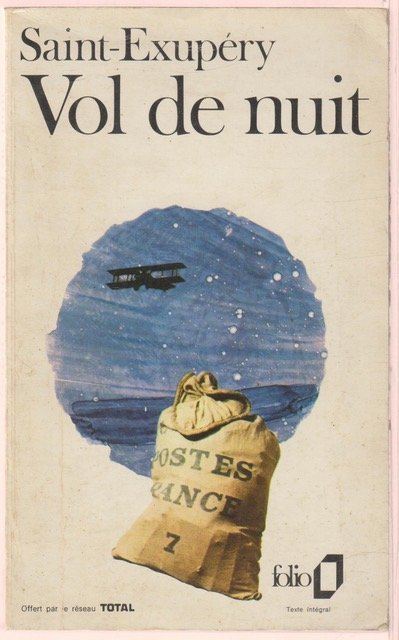

There was apparently a lot of downtime at his various postings. Which he used to good advantage, writing books about his life. For his first book, Courrier Sud, he chose his adventures in the Aéropostale and Cape Juby. His second book Vol de nuit was about his years in Buenos Aires.(Figure 11) For this book, published in 1931, he won the Prix Femina, the French literary prize decided each year by an all female jury.

Figure 11. Vol de Nuit (Night Flight), Saint-Exupéry, 1931.

In 1931, Saint-Ex also married Consuelo Suncin, a once-divorced, once-widowed Salvadoran writer and artist.(Figure 12) The flying author / writing pilot was thoroughly enchanted by his wife. But by all accounts, theirs was a particularly difficult marriage. During their years together (and there were only 13), it’s not clear who cheated on whom more, who left whom more frequently. He was always traveling. She was fiercely independent. But she was his rose. (Figures 13, 14)

Figure 12. Consuelo Suncin de Sandoval

Figure 13. Le Petit Prince taking care of his flower/rose, Saint-Exupéry sketch, 1942

Figure 14. Le Petit Prince with his rose

“It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important. You become responsible forever for what you’ve tamed. You’re responsible for your rose.” (Le Petit Prince)

In December 1935, Saint-Ex and his engineer, André Prévot participated in the Paris-Saigon air race. They crashed into a sand dune in the Libyan desert. (Figure 15.) Lost, they wandered and eventually ran out of food and water. Dehydrated, they began to hallucinate and see mirages.

Figure 15. Saint-Exupéry following crash in Libyan desert, 1935

“What makes the desert beautiful, said the little prince, is that somewhere it hides a well…” (Le Petit Prince)

And Saint-Ex encountered some foxes. (Figure 16) "To me, you are still nothing more than a little boy who is just like a hundred thousand other little boys. And I have no need of you. And you, on your part, have no need of me. To you I am nothing more than a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes. But if you tame me, then we shall need each other. To me, you will be unique in all the world. To you, I shall be unique in all the world....” (Le Petit Prince)

Figure 16. Le Petit Prince meets a fox, Saint-Exupéry drawing

After three days, a Bedouin found the nearly dead Saint-Ex and Prévot. He administered a native rehydration treatment and saved their lives. This brush with death was the focus of Saint-Ex’s 1939 memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, (Figure 17) which won a National Book Award.

Figure 17. Wind, Sand and Stars, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

And now, finally, we arrive at the year we have been waiting for, 1940. After the German invasion, Saint-Ex fled France for New York via Portugal. He was planning a brief stay. His goal was to convince the U.S. to enter the conflict against Nazi Germany. Instead, he was in North America for 28 months. As he waited, he wrote, both Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), and Lettre à un otage (Letter to a Hostage), dedicated to his countrymen in Nazi occupied France.

He was depressed and frustrated by his unsuccessful his efforts to convince the American government to enter the war against Nazi Germany. That was when the French wife of one of his publishers suggested he write a children's book. He agreed. Saint-Ex wrote and illustrated Le Petit Prince in New York City and upstate New York from mid-to-late 1942. ‘He crafted a tale about an interstellar traveler in search of friendship and understanding.’ Maybe for children, maybe for their parents.

He wrote late at night as he always did. And as he had done all those years earlier, as a young boy writing poetry and wanting his family’s immediate reaction, he frequently called friends in the middle of the night and read a few pages aloud to them, to get their reaction.

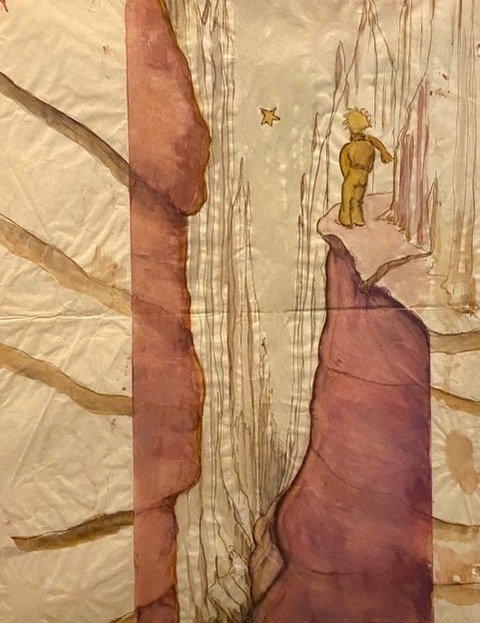

The Morgan manuscript of Le Petit Prince, with additional, mostly unpublished sketches, drawings and watercolors, is the highlight of this exhibition. It is the first time the collection has been seen in France. What we see is a record of an author’s creative process. Working on onion skin paper, (Figures 18, 19) Saint-Ex wrote multiple drafts of each chapter. He deleted entire passages and episodes. He pared down the text to its essentials. The little book is the sum total of all the ‘decisions and excisions’ the writer made along the way.

Figure 18. Watercolor sketch of King, Saint-Exupéry, 1942

Figure 19. Boa constrictor after swallowing an elephant, drawing, Saint-Exupéry, 1942

Though Saint-Ex began drawing when he was a child and unhappily attended architecture school for a few months when he was twenty, he had no formal training as an artist. But he was an inveterate doodler. He had never illustrated a book before, either. But he wanted to illustrate Le Petit Prince himself. He already knew the title character, he had been sketching versions of him in the margins of letters and manuscripts for years. The Morgan drawings, mostly ink and watercolor, aren’t only the iconic images you know from the book. Some were excluded from the book and almost all were substantially reworked. Just a handful were published with only minor revision. But the process is here for us to see and it’s fascinating. The Morgan collection includes 35 full-page drawings and eight pages of manuscript with sketches. When he was done writing and drawing, Saint-Ex didn’t just hand over the text and images to his publisher, he participated in the layout, too, stipulating the position, size and captions for the illustrations. (Figures 20, 21, 22)

Figure 20. Watercolor sketch of the businessman, Saint-Exupéry,1942

Figure 21. Watercolor drawing of Le Petit Prince and his star, Saint-Exupéry, 1942

Figure 22. Final design at Le Petit Prince exhibition, Musée des arts decoratifs

Le Petit Prince was first published in New York, in both English and French, in April 1943. Although Reynal & Hitchcock had published Saint-Exupéry’s earlier books in English, this was the first and only time it issued one of his books in the original French as well. But there was no other choice, Saint-Ex’s French publisher Gallimard was not in business in 1943.

Just as Le Petit Prince went into production, Saint-Exupéry learned that he would be redeployed under Allied command. He said good-bye to his friends and sailed for North Africa, a single copy of the newly printed French-language edition of his book with him. But he didn’t take any of his drafts or sketches or drawings. And he didn’t entrust them to a dear friend for safekeeping, until he returned. While it is true that Saint-Ex wrote much of The Little Prince in a house that he and his wife had rented in Long Island during the summer of 1942, it is also true that he wrote and rewrote his manuscript in the Upper East Side apartment of his friend and lover, Silvia Hamilton. And so, just before he left New York, he knocked on Hamilton’s door and gave her this treasure.

She later recalled that he said, “I’d like to give you something splendid but this is all I have.” In a paper bag that he casually tossed onto a table, were the manuscript and drawings for Le Petit Prince. Over the years, Silvia Hamilton gave a few sheets away, to friends and family. But mostly she kept her gift intact. She finally sold the present she had received from her long ago lover, to the Morgan Library in 1968, 24 years after she received it. Perhaps it is fitting that the manuscript for a book that was conceived and written in New York, that was first published in New York, has remained in New York.

The penultimate room in the exhibition is Saint-Ex’s final days as a pilot, defending his country, prepared to die for his country. (Figure 23) Photos attest to the truths that he was unable to bend over so someone had to get him into his uniform, someone had to put his shoes on for him. He had to be loaded into the plane. And once inside, old injuries meant he couldn’t move his head. And planes had changed so dramatically during the twenty years Saint-Ex had been flying, he really didn’t know, even with training, what the planes were capable of doing. He had already crashed once since returning. And his American commander wasn’t keen on losing another aircraft. But Saint-Ex insisted and persisted and on 31 July 1944, he took off from Corsica on a lone reconnaissance mission over southern France. The little prince had disappeared without a trace from the Sahara, and like him, Saint-Exupéry just disappeared, too. Weeks later, Allied troops marched into Paris. The French publisher Gallimard, finally published its own edition of Le Petit Prince in 1946.

Figure 23. Photo of Saint-Exupéry getting ready for take-off

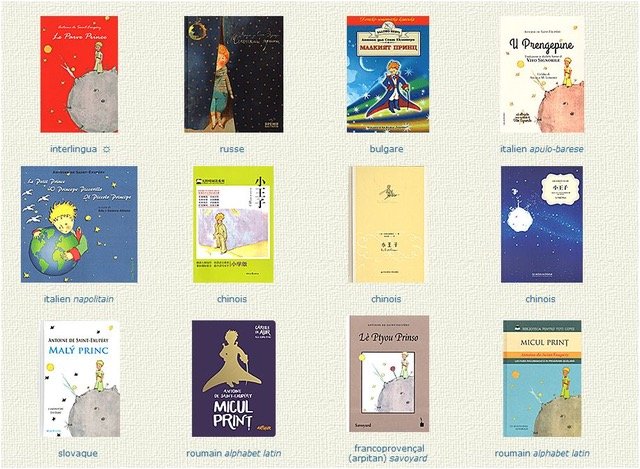

The final room is filled with copies of Le Petit Prince in a dizzying array of languages. (Figure 24) We are told that the book has been translated into five hundred languages, that five million copies are sold each year, and that it is “the most widely read book in the world after the Bible”. And it is not only languages into which it has been translated, but dialects, too.

Figure 23. Photo of Saint-Exupéry getting ready for take-off

"Goodbye," said the fox. "And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye." Le Petit Prince

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.