How to Get Your Proust On

“Marcel Proust A Parisian Novel: Musée Carnavalet”

I spent a lot of time in graduate school. And a lot of that time was spent around people who told punch lines to jokes in Latin. It was all very precious. But I never ran into any Proust cults. I guess it was because the art history department shared a building with the art & architecture departments. We were the bookish ones and most of us were reading post-modern art theory and looking at catalogues raisonné.

It wasn’t until I moved to San Francisco and started taking French classes, that I came into contact with Proust-heads (a reasonable term I think, living as I was in the land of Grateful Dead Heads). I learned then about the classes and study groups whose members plow through one or another or all of the 7 volumes of Remembrances of Things Past, preferably in French. Meeting weekly or monthly for years on end. To read a few pages together. To discuss a few pages together.

I assumed that I would get to Proust, eventually. I just didn’t know what the hook would be. (and whether I should finish Middlemarch first) Now I am ready, thanks to the exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet, Marcel Proust A Parisian Novel.

It began with the seductive exhibition poster. (Figure 1) A painted portrait of Proust at 21. A pale young man, with dreamy brown eyes and an embarrassment of a mustache just above his sensuous lips. The portrait painted in 1892 by Jacques-Émile Blanche shows Proust, like any other young dandy or flaneur of the Belle Époque, dressed for an evening out. The orchid on his lapel had meaning at the moment and would continue to have meaning. Proust had his first asthma attack at age 10. From that moment on, flowers had to be avoided. Except for orchids which have no scent. His asthma worsened with age. Eventually his housekeeper had to question visitors before they were allowed entry. Had they been near flowers? If the answer was yes, the housekeeper’s answer was no. Come back another time and take a flowerless route.

Figure 1. Marcel Proust, Jacques-Émile Blanche, 1892

According to one Proustian botanist, the orchid in Proust’s lapel is not just any orchid, it is a cattleya orchid. Which appears in the first volume of Proust’s opus, Du Côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way) published in 1913, 21 years after this portrait was painted. When Proust was twice the age that he is pictured here. Spoiler alert: This is when Odette de Crécy, wearing a cattleya orchard on her bosom, first makes love with Charles Swann. In one of those ‘how cute is that’ thing lovers do, every time they refer to sexual intercourse after that, they call it, “faire cattleya”.

Just as an aside, like Picasso and Andy Warhol, and my son, too, Proust was a mama’s boy. A portrait of his mother Jeanne, (Figure 2) hung in his apartment and hangs in this exhibition. When a child, Proust was asked what was the worst thing he could imagine. He said, “to be separated from Maman”. (Who asks a child that kind of nightmare inducing question?) As it turned out, it wasn’t until his mother died, in 1905 that Proust actually got to work. Although before her death, he and Maman translated two volumes of John Ruskin’s works together (her English was better than his).

Figure 2. Mme Jeanne Proust, Anais Beauvais, 1880

This exhibition is divided into two sections. The first section explores the Paris of Marcel Proust. He was born in Paris. He died in Paris. It’s a big city but Proust’s Paris wasn’t big. As the exhibition notes, he moved between the Parc Monceau, the Place de la Concorde, Auteuil, the Bois de Boulogne and l’Étoile.

The second part of the exhibition “opens on the fictional Paris created by Marcel Proust. Following the architecture of the novel and evoking emblematic places in the city, it offers a journey through the novel and the history of the capital, focusing on the book’s central characters.” (exhibition press kit)

And how does the exhibition do this? Well, of course, there are the requisite paintings, prints and photographs. furniture, tapestries and objets. There are also film clips, interviews and maps that make for a lively telling of Proust’s story.

Right in the center, dividing the Paris Proust grew up and matured in and the city Proust imagined, is a replica of the room in which he wrote and virtually lived for the last third of his life: his cork lined bedroom. (Figures 3, 4) The cork panels prevented pollen and dust from making his allergies and asthma worse. And they reduced noise, especially from the apartment above. To help with that, Proust paid the servants walking around above him to wear slippers. Proust’s bed, walking cane, beaver collared manteau (he was always cold) and chaise longue are here, They were all in his bedroom when he died. Also here, a framed lock of hair, cut at his death and a photograph by Man Ray taken at the same time. (Figure 5) Those items belong to the Carnavalet (the city’s attic) and are always on display. But never with contextualization this exhibition offers.

Figure 3. Proust’s bedroom, Musée Carnavalet (permanent collection)

Figure 4. Proust’s bedroom, detail, temporary exhibition, Musée Carnavelet

Figure 5. Proust on death bed, Man Ray, photo 1922

There are also some neat things in this cork lined room, unexpectedly modern, state of the art things. A typewriter on which his secretary transcribed his manuscript, a telephone and most interestingly a “théâtrophone” (Figure 6) a service Proust subscribed to which allowed him to listen (in stereo on two headphones) to live performances from the Opéra Garnier over the telephone.”

Figure 6. Théâtrephone, Musée Carnavalet

If you come to the exhibition, expect lots of people and expect to return to see things you hadn’t noticed the first time. There are two film clips, one from a film called Swann in Love dates from 1984 and stars a perfectly cast Jeremy Irons. Tall, thin and elegant, he seems made for the evening costume he wears. A clip from another film shows the Baron de Charlus in an all-male brothel. In the disturbing clip that I kept looking at / turning away from, the Baron is being beaten, something that he seems initially surprised about but, from what I could tell, came to enjoy. Startle Pain Pleasure Repeat is my thumbs up review.

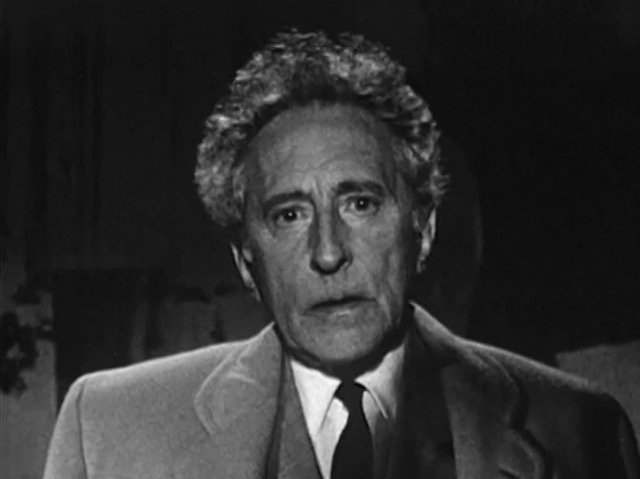

And there are video interviews of people who knew Proust, like the surrealist poet, playwright, filmmaker Jean Cocteau (Figure 7) who describes a visit to Proust’s apartment. Asked to read aloud from his novel by one of his guests, Proust couldn’t stop laughing at what he was reading. And he kept repeating “This is silly! This is silly!’. Did you know that Proust’s book is funny? Now you do.

Figure 7. Jean Cocteau recounting his times with Marcel Proust

Another interview is with Celeste Albaret, Proust’s housekeeper / secretary for the last 8 years of his life. Interviewed in 1962, forty years after Proust’s death, she teared up as she recounted his final days. “He told me that death was coming for him, and that he would hate to have worked so hard and left (his manuscript) unfinished. One morning when I arrived, he said, ‘Dear Céleste, I have great news to tell you, something immense, so good. I wrote the word ‘Fin’. I can die now’.” And he did.

We know that Proust was Jewish on his mother’s side and that he was homosexual on all sides. He linked Judaism to homosexuality. But I am not going to tell you how or talk about either because on April 14 and running through the summer, the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme (MahJ) is presenting an exhibition called “Marcel Proust. On his mother's side”. I am expecting to learn more about and then tell you about Proust and his fellow Jewish esthetes during the Belle Époque. The Dreyfus Affair and Impressionism. Homosexuality and Antisemitism.

As I mentioned at the beginning, I found the hook that will take me to Proust. Actually three paintings and a discovery at the Carnavalet’s book shop.

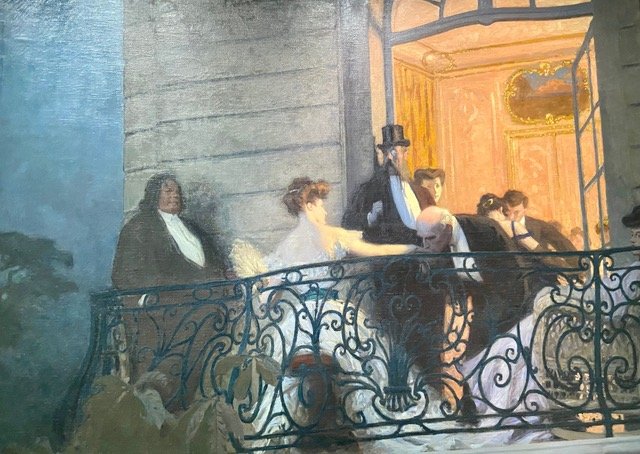

Two of the paintings depict elegant, exquisitely attired people enjoying themselves in equally beautiful, equally sophisticated settings. (Figures 8, 9) The paintings reminded me of the Yves Saint Laurent exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, of the costumes he designed for the Bal à la Proust that was held in 1971, to mark the centennial of Proust’s birth. (Figure 10) Another of the paintings was unexpected. And again related to the Yves Saint Laurent multi-museum exhibition. As I was making my way to the Galerie d’Apollon, that magnificent room at the Louvre to see jewel encrusted jackets by Saint Laurent, I promised myself I wouldn’t just walk through this museum ignoring the masterpieces between myself and my destination. At one point, as I walked along endless corridors, I glanced left instead of right. And voila, fabulous frescoes by Botticelli. (Figure 11) Frescoes that I know, that I love. And there they were again, in a painting at this Proust exhibition at the Carnavalet. (Figure 12)

Figure 8. Soirée Pre-Catelan, Henri Grevex, 1909

Figure 9. “Le Balcon” René-Xavier Prinet, 1905-06

Figure 10. Bal a la Proust, costumes by Yves Saint Laurent, 1971, Musée d’Orsay

Figure 11. Venus and the Three Graces, Botticelli, fresco, 1475-1500, Musée du Louvre

Figure 12. Au Louvre devant une fresque de Botticelli, Norbert Goeuneutte, 1892

But the clincher was the prolonged perusal in the Carnavalet bookshop. I was looking for a birthday present for Peter, my friend from Baltimore who took me to Taillevent for his birthday (and was given the menu with the prices). He and a small group of friends have met monthly for years for an afternoon with Proust. I bought Peter a ticket to the exhibition and the exhibition catalogue, only available in French but what the heck, he and his friends read Proust in the original. Just as I was vetoing the socks with Proust’s face on them (a difficult decision, I may have to go back) I noticed a book called Paintings in Proust. After ascertaining that Peter already owned the book (in both French and English), I bought a copy for myself (in English).

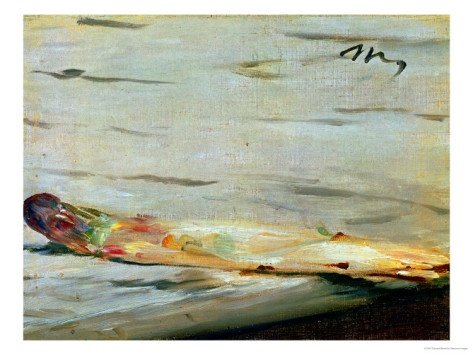

I immediately began to read the book. In the introduction I came upon a story that I already knew. That anybody who has taken an upper level undergraduate art history course on 19th century French art knows. Edouard Manet painted a bunch of asparagus. (Figure 13) A wealthy patron bought it and gave the artist 1000 francs, 200 francs more than the asking price. The next day, the painter sent a package to the patron. In which there was another painting, of a single asparagus, (Figure 14) with a note, this one asparagus had slipped from the bunch.

Figure 13. Bunch of Asparagus, Edouard Manet, 1880

Figure 14. Single Asparagus, Edouard Manet, 1880

When I was reading Edmund de Waal’s book Letters to Camondo I was delighted to learn the identity of the patron who purchased Manet’s asparagus. It was Charles Ephrussi, an ancestor of de Waal and related to the Camondo by marriage. Like all rich families everywhere, these Jewish ones intermarried.

But there’s more. Not only was Charles Ephrussi, the man who bought the asparagus still life, connected to the Camondo family, he, with his uncle Charles Haas, he was the model for Charles Swann in Proust’s novel.

And still more. From the asparagus anecdote “Proust fashioned a tiny morality play …that involved a painting, also of asparagus, by Elstir” (Proust’s fictional artist). The Duc de Guermantes, in his ‘sumptuous dining room, eating asparagus’ expresses indignation to the Narrator because Swann suggested that he buy Elstir’s painting of a bunch of asparagus. But the duke thinks the price is outrageous. “Three hundred francs for a bundle of asparagus! A louis, that’s as much as they’re worth, even early in the season.” Wait, did he really confuse the price of fresh asparagus with a delightful, now priceless painting of one? What a boor.

As Karpeles notes, Proust transformed a charming celebration of the generosity of an artist and his patron into a tale of arrogance and ignorance.

Kerpales book correlates Proust’s text with exact or approximate images, depending upon how specific Proust was. Karpeles has been criticized for being mechanical. But even if his interpretations fall short for the more exigent Proust scholars (you know who you are), providing really good quality images gives Proust readers the tools to make their own observations.

I cannot tell you how excited I was to see color reproductions of the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel in Padua. (Figure 15) This jewel box of a space, frescoed by Giotto (1304-06) depicts scenes from the life of the Virgin, the life of Christ and Christ’s Passion. Below and ‘en grisaille’ (painted to look like stone) are Personifications of the Virtues and Vices. Karpeles quotes only a fraction of Proust’s musings on these fabulous figures. But that’s okay, if you want to know more, read the book, as they say.

Figure 15. Interior, Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua, Giotto, 1304-06

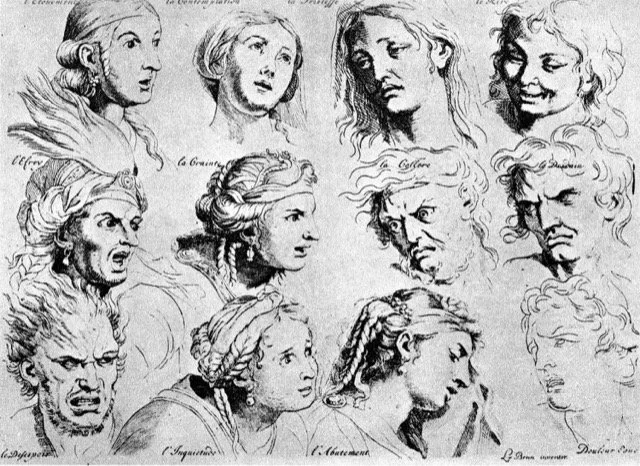

In one passage Proust talks about a servant girl he saw one year at Cambray. She was so near giving birth that she looked like Giotto’s figure of Caritas from the Arena Chapel, (Figure 16,) so square and so matronly. Proust muses that these personifications display none of the virtues or vices they personify. And I thought but surely Proust knew that personifications require only attributes. For Charity it is the basket of plenty that she shares. All of the attributes are found in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia, first published in 1593. (Figure 17) What Proust is looking for in these faces is emotion. Those are in Charles Le Brun’s compendium called ‘Tetes d’Expressions,’ or ‘Trait é des Passions’ first published in 1668, (Figure 18) which shows how to show emotions, like Envy and Terror, etc.

Figure 16. Caritas, Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua,Giotto, 1304-06

Figure 17. Personification of America, Cesare Ripa, Iconologia, 1603

Figure 18. Trait é des Passions, Charles Le Brun, 1668

If I were to rhapsodize about Giotto’s Virtues and Vices, (I read somewhere that Proust planned to structure his novel around them) if I were to think about when I first saw them, I would have been older than Proust’s Narrator but I think no less impressionable. For me, it is what is happening beneath Justice and Injustice. Under Justice, women are safe to dance in the open. (Figure 19) Under Injustice, soldiers rape and rob. (Figure 20) Like the Lorenzetti allegory of Good and Bad government in Siena painted a little later, where women dance in the streets without fear when towns are presided over by Good Government (Figure 21) and women are (once again) robbed and raped when Bad Government takes over. (Figure 22)

Figure 19. Justice, Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, SEE BELOW, WOMEN DANCING Padua, Giotto1304-06

Figure 20. Injustice, Scrovegni SEE BELOW SOLDIERS RAPING/ROBBING (Arena) Chapel, Padua, Giotto1304-06

Figure 21. Girls Dancing, detail from Allegory of Good Government, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Palazzo Publico Siena, 1337-39

Figure 22. Detail from Allegory of Bad Government, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Palazzo Publico Siena, 1337-43

These painted figures are my madeleines. They evoke so many memories - of seeing them in books and then in situ. Of writing about them in my dissertation and explaining them to students and now to you. Did Proust know the frescoes in Siena? Did he write about them? I guess I will just have to read the books to find out.

Finally I came upon this, by M-J Eschmann (The Collector 2020) who explains Proust’s opus this way. The Narrator, searching for the meaning of life, first posits that it lies with social success. Then with love. Finally he understands that art is the “only possible source for the meaning of life”. So, there you go.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.