When Louis Quinze was a Kid

La Régence à Paris, Musée Carnavalet

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week, we’re off to the recently opened exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet, ‘La Régence à Paris (1715 - 1723) The Dawn of Enlightenment’. And once again, memories of exhibitions past enhance my appreciation for the exhibitions I’m seeing now. This one’s here until the end of February.

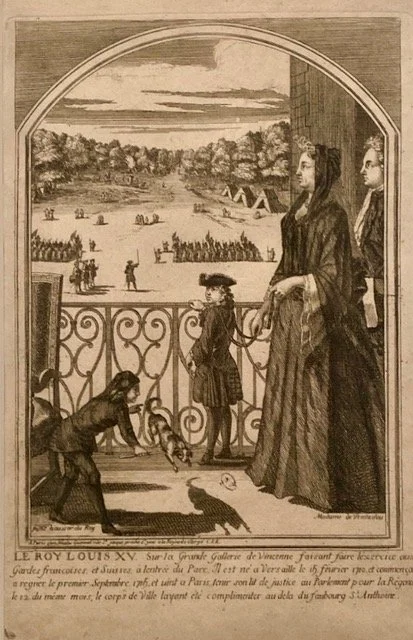

Let’s begin with a definition of La Régence. The term refers to eight years in Lous XV’s life, from the death of his predecessor, Louis XIV in 1715 to his own coronation in 1723. Louis XV was 5 when Louis XIV died. (Figs. 1, 2) He was 13 when he was crowned. During those 8 years, France was ruled by Louis XIV’s nephew, Philippe II d’Orléans, whose title was Prince Regent. (Fig. 3)

Figure 1. Louis XIV, L’état c'est moi, Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701

Figure 2. Louis XV in Coronation Robes, Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1715

Figure 3. Philippe II, Duke d’Orleans, Prince Regent

We all know that the English Queen Elizabeth II’s father was the second son. Not the heir but the spare (think Prince Harry). The improbability of George V becoming King of England following the death of his father, Edward VII, was obvious. It required his brother’s abdication to marry the twice divorced American, Wallace Simpson. But that surprising turn of events is nothing compared to the hurdles that should have kept Louis XV from ever becoming King of France.

This question that will provide the explanation: if Louis XIV was 76 when he died in 1715, why was his heir, Louis XV only 5 that year? Turns out, Louis XV was Louis XIV’s great-grandson. Louis XIV's eldest son should have succeeded him. If something happened to him, then his eldest son, Louis XV’s own father should have become King. And if something happened to Louis XV’s grandfather and father, then one of Louis’ two older brothers were in line ahead of him.

What happened? That winning combination of sickness and death. Louis XV’s grandfather died of smallpox in 1711. Louis XV’s father died of measles in 1712. When Louis’ older brother contracted measles, (the other older brother was already dead), the doctors treated him in the traditional way, by bloodletting. Louis’ brother, just 5 years old, died from that lethal combination of disease and treatment. When Louis got the measles, his doctors didn’t have any new tricks up their collective sleeves. So they opted for bloodletting. Which only made little Louis weaker. That’s when Louis’ governess, Mme de Ventadour, (Figs. 4, 5, 5a) took the matter into her own hands. She hid her 2 year old charge in a palace closet and nursed him back to health herself. So, when Louis XIV finally died in 1715, this family-less orphan, this third great grandson of Louis XIV became Louis XV. (Fig. 6)

Figure 4. Print showing Louis’ governess holding onto him by a leash

Figure 5. Meeting of Parliament at which Louis XV is in attendance, with his governess

Figure 5a. Detail of Fig. 5, Mme Ventadour is only woman here, next to her charge

Figure 6. Louis XV with his ministers

But he couldn’t rule, not yet. In 1374, Charles V had issued a royal decree stating that a king could not ascend to the throne if he was younger than 13. A regent would be required to govern the country until the king’s 13th birthday. A regent was most often the young king’s uncle or mother, as for example, Marie de' Medici, Henri IV’s wife, who, upon her husband’s death, served as regent for 7 years, until her son, Louis XIII, turned 13. In Louis XV’s case, all of his close relatives were dead.

Except his great-uncle Philippe II, Duke of Orléans. Who Louis XIV liked very little and trusted even less, something about him being a drunk and a libertine. So, just before he died, Louis XIV changed his will to weaken the regent’s power. Which Philippe reversed as soon as he could. Well, actually by convincing the Parliament to do it. And they agreed. Why? Because Philippe restored to Parliament a right Louis XIV had annulled. Called the droit de remonstrance, it was Parliament’s right to challenge a king’s decision. It didn’t matter to Philippe, he was never going to be king. But it became a serious problem for Louis XV’s grandson and successor, Louis XVI.

When the full power to act in the name of the king was restored, the Regent started making decisions. Like about where the court should live. A week after Louis XIV died, the Regent moved the boy king out of Versailles and into Paris. Very quickly, the Regent’s home, the Palais-Royal, replaced Versailles as the center of power. And the period known as the Regence began.

Last year, there was an exhibition at Versailles about Louis XV, whose nickname was The Beloved. (Fig. 7) It was a sumptuous, over the top, exhibition as exhibitions at Versailles are wont to be. We learned about Louis’ crazy childhood, the subject of the current exhibition at the Carnavalet. We learned about his fascination with all things scientific, which also figures in the Carnavalet exhibition. We learned about his mistresses, chief among them Mme de Pompadour, for whom sculptures by J-B Pigalle (Fig. 8) and paintings by Boucher signaled when their relationship turned from amants aux amis (lovers to friends). And Mme du Berry, who rejected the glorious panels painted by Fragonard that are now at the Frick Collection, New York (Fig. 9). Not forgetting, of course, Mlle O’Murphy, (Fig. 10) whose lovely bottom, painted by Boucher, was enough to entice the king, and she, too became his mistress. The image of the adult Louis XV that comes most readily to my mind is Rip Torn (Fig. 11) as Marie-Antoinette’s grandfather in law in Sophia Coppola’s film, Marie-Antoinette.

Figure 7. Louis XV Passions d’un roi, Exhibition at Versailles, 2022

Figure 8. Mme Pompadour as Friendship, J-B Pigalle

Figure 9. Progress of Love, Honoré Fragonard, 1771

Figure 10. Mlle O’Murphy, François Boucher, 1752

Figure 11. Rip Torn as Louis XV with Mme du Berry in Marie-Antoinette, Sophia Coppola

The exhibition at Versailles showed us Quinze as Conqueror (of the fairer sex). Quinze as Kid, during the Regency, is the focus of the Carnavalet exhibition

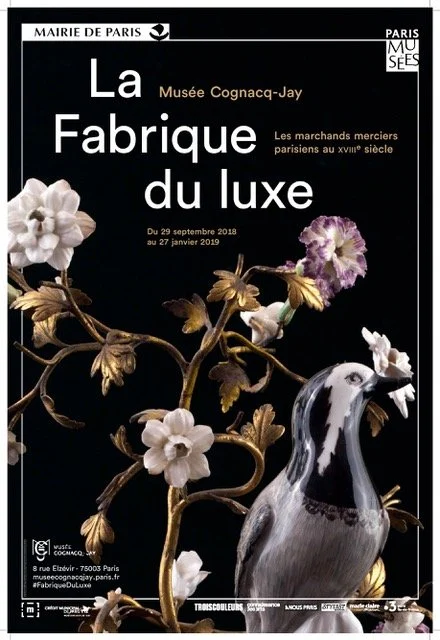

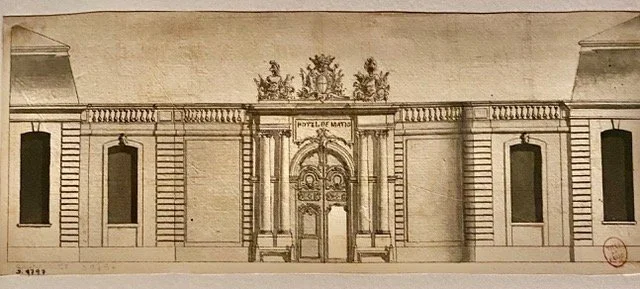

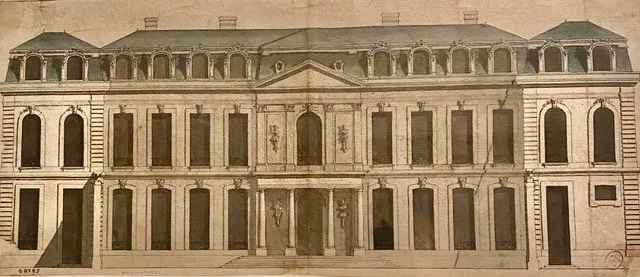

A couple years ago, at the Musée Cognacq-Jay, there was an exhibition entitled “La Fabrique du lux, les marchands merciers Parisians au XVIII siecle”. (Fig. 12) It was a celebration of all the fabulous decorative arts objets that began to be produced in quantity during the Regency. What caused the sudden demand? The young king’s departure from Versailles to Paris instigated by the Prince Regent. Not surprisingly, there was a housing shortage. Dozens of new homes were designed and built between 1716 - 1725 to accommodate all the nobles who moved to Paris.The Carnavalet exhibition tells the story of these hotel particuliers - their location and the architects who designed them, using interactive displays that are fun and easy, unless you get impatient waiting your turn. (Figs. 13, 14) This section of the exhibition is called, “Fièvre de construction Faubourg Saint-Honoré.” The most beautiful among the mansions is l’hôtel d’Évreux, which has been, since 1871, the Palais de l’Élysée, the residence of the presidents of France. (Fig. 15).

Figure 12. La Fabrique du lux, Musée Cognacq-Jay

Figure 13. Hôtel de Matignon, Paris

Figure 14. Hôtel d’Évreux, Paris

Figure 15. Palais de l'Élysée, (formerly Hôtel d’Évreux

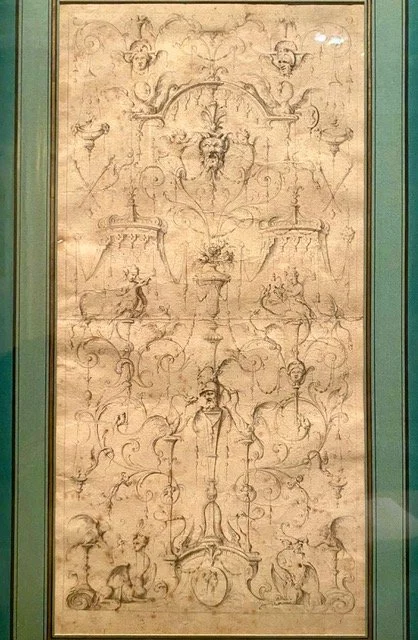

After these hotel particuliers were built, they had to furnished, bien sûr - with objects and paintings and furniture that fitted domestic scale residences. Grand domestic scale residences, to be sure, but obviously much smaller than Versailles. In the exhibition at the Cognacq-Jay, we learned about the central role played by the Marchands-merciers. The dealer-decorators who employed artists to provide designs for furniture and objets (Fig. 16) and who found craftsmen to make them for particular clients or to offer them for sale in their shops. (Figs. 17, 18) A sampling of these exquisite objets is on display at the Carnavalet, too. And if you save your ticket, you can book to visit, free of charge, Saturdays only, to the Galerie Dorée of the Hôtel de Toulouse (Fig. 19) in Paris, which is now the headquarters of the Banque de Paris.

Figure 16. Decorative Patterns

Figure 17. Porcelain figures and flowers with a clock, Cognacq-Jay exhibition

Figure 18. Porcelain vessels, Versailles exhibition

Figure 19. Galerie Dorée, Banque de Paris (formerly Hôtel de Toulouse, Paris)

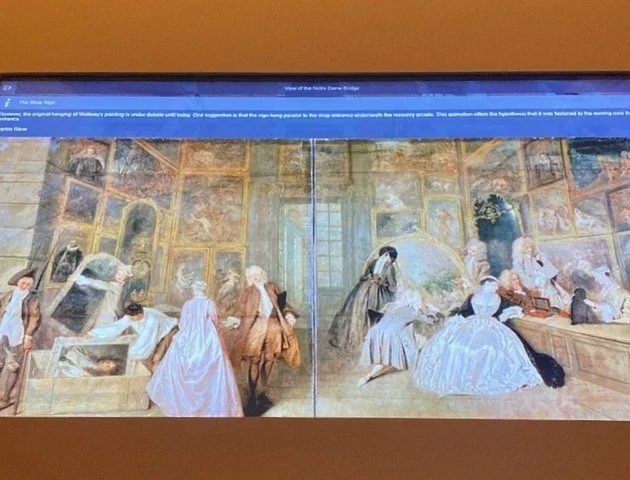

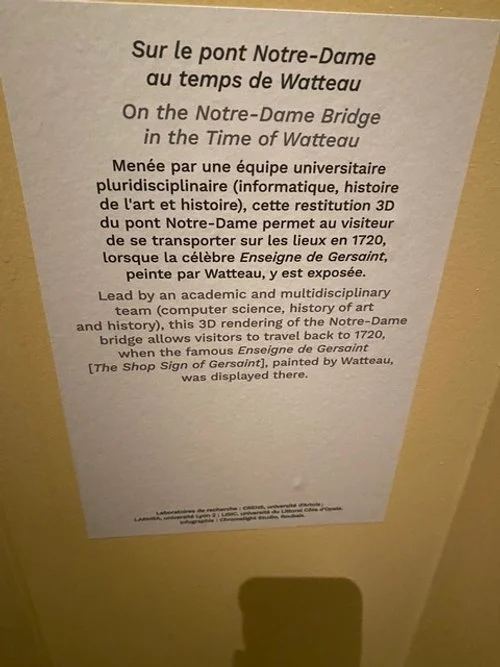

The piece de resistance at the Cognacq-Jay exhibition was a life-size recreation of one of my favorite paintings of all times, Antoine Watteau’s l’Enseigne de Gersaint, (The Shop Sign of Gersaint), (Fig. 20). Watteau painted it in 1720 for the marchand-mercier, (and art dealer) Edme François Gersaint. Created as a shop sign, it shows the interior of Gersaint’s shop, though considerably exaggerated since it was basically a closet size public space with a back room. But its location was perfect - on the medieval Pont Notre-Dame. Watteau’s painting is featured at the Carnavalet, too, as an interactive, 3-D map that you can manipulate to see the shop from a variety of angles as you cross the bridge where it stood. (Figs. 21, 22)

Figure 20. l’Enseigne de Gersaint, Antoine Watteau, 1720

Figure 21. l’Enseigne de Gersaint, Carnavalet exhibition

Figure 22. Directions for interactive multidisciplinary view of Pont Notre-Dame (en panne)

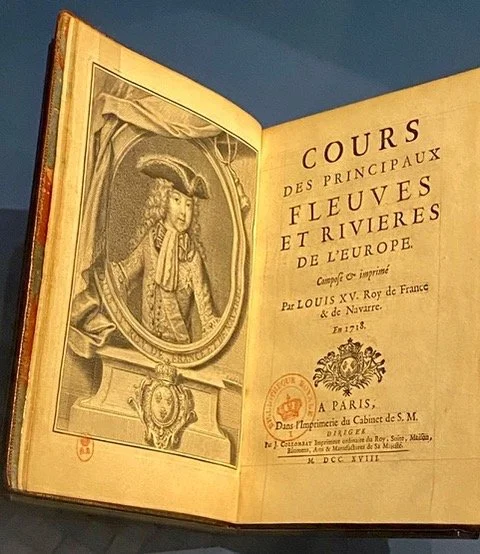

Even though Louis was not old enough to rule, when he reached the age of 7, in 1717, he was too old to stay with his beloved governess. His education became the responsibility of a governor who taught the young King how to review a regiment and how to receive royal visitors. How to ride horseback (Fig. 23) and how to hunt. He learned Latin and Italian, (Fig. 24) history and geography, (Figure 25) astronomy and mathematics and drawing and cartography. Science and geography continued to fascinate the king throughout his life. (Figs. 26, 27). Surrounded as always by beautiful objects. (Figs. 28, 29, 30)

Figure 23. Louis XV, boy king on horseback

Figure 24. Louis XV boy king doing his studies

Figure 25. One of Louis XV’s school books

Figure 26. Louis XV’s Barometer & Thermometer

Figure 27. Louis XV’s Clock with Globe held by Hercules, 1712

Figure 28. Perfume fountain

Figure 29. Cartography Table

Figure 30. Sedan Chair, 1710-20

Alas, the Regency was not all fun and games. Thanks to John Law, (Fig.31) the Scottish economist. He managed to gain control of and then ruin the economy of France. Here’s how he did it. In 1716, he convinced the French government, aka the Prince Regent, to let him open a bank. It was one of the earliest banks to issue paper money. Which Law promised could be exchanged for gold. The trouble began when Law combined his bank with the Louisiana Company, which had exclusive privileges to develop the French territories in the Mississippi Valley of North America. Law persuaded wealthy Parisians to invest in the Mississippi Company. The stock quickly soared and then just as quickly collapsed (this was 1720) taking the bank with it. John Law fled France for Venice to avoid incarceration. Law, labeled a gambler and a playboy in one contemporary journal, spent the rest of his life gambling, though presumably with less at stake than the finances of an entire country.

Figure 31. John Law

Let’s see, what else happened during the Regency. Well, in 1719, France, England and the Dutch Republic went to war against Spain. After Spain’s defeat, a Franco-Spanish treaty was signed (1721). What better way to strengthen the alliance than with a royal marriage. Little Louis, then aged 9, was betrothed to the 7 year old daughter of Philip V of Spain. (Figs. 32, 33) The future bride arrived in France, moved into the Louvre (a palace at the time), and waited to grow up. After a few years, everyone agreed that the wait would be too long for this little girl to start giving birth to royal heirs. So she was sent back to Spain.

Figure 32. Louis XV and his child betrothed

Figure 33. Louis XV’s child bride

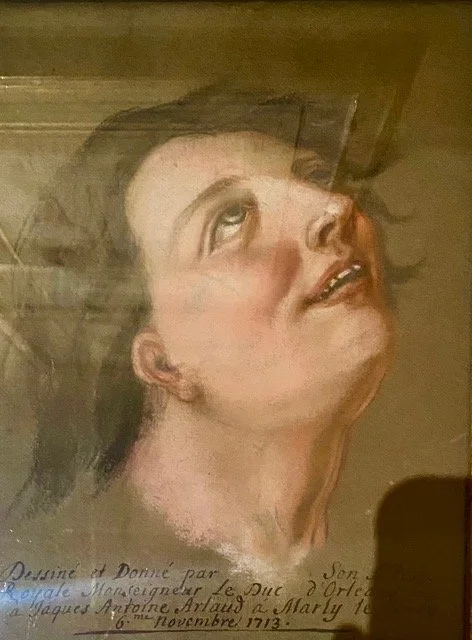

Anything else? Yes, actually, there was the theatre - Italian (Fig. 34) and French. And there was art - Rococo fantasies by Watteau and Gillot and Oudry. (Fig. 35) And in this exhibition, there was a fair bit about the Regent’s own artistic skills. (Figs. 36, 37)

Figure 34. Italian Ballet with Children, Antoine Watteau

Figure 35. Commedia dell'Arte, Jean-Baptiste Oudry

Figure 36. Drawing by Prince Regent, Philippe II, d’Orléans

Figure 37. Tapestry after design by Prince Regent, Philippe II, d’Orléans

Although it doesn’t figure prominently except in the title, the Age of Enlightenment began with the Regency, with the publication of works by Montesquieu and Voltaire. Eight years doesn’t sound like a long time, but it was long enough to put in place the conditions for the chain of events that led first to the American Revolution and then to the French Revolution, followed by the beheading of the king and the crowning of the emperor who succeeded him.

Thanks so much to those of you who have taken the time to Comment, below are a few. I am grateful for them all. Gros Bisous, Dr. B.

New Comment on How to Get Your Proust On:

I’m a retired English professor (but French major at Yale), who used the pandemic lockdown to read the whole of Proust (in English translation). To my amazement, I discovered that the hero of the novel. (not Proust himself but his narrator Marcel) is a reflection of myself—my personality, interests, frustrations, and fascinations. Because of this naturally I could not stop reading. I found myself on almost every page! The novel is about self-discovery, and the vehicle for this is art. I share this viewpoint. But I am saddened by the fact that Proust, unlike myself, never experienced the satisfaction of true, lasting love. And so the long novel was surprisingly a revelation for me, showing me so much about who I am. No book in my long life of reading has done this. Jay

New comment on The Ephemeral Nature of Time:

Superb articles as always, Barbara

New Comment on Not Smelling Like a Rose:

Just catching up but appalling doesn’t do justice to Stein’s self serving behavior. For what it’s worth, I’ve always thought she was greatly overrated as a writer and celebrated much more due to her story, money and influence than to any talent. I remember an exhibit years ago at the de Young where I’d thought she’d shafted her brother. I could be mistaken but that was my impression and consistent with the museum texts explaining her wartime behavior. Love being right. ! Nikki