The Ephemeral Nature of Time

Musée des Archives Nationales, Paris

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. This week, as last, I have been busy blitzing my way, slowly and (hopefully) thoughtfully through as many exhibitions as I can visit. One of the most satisfying aspects of learning something new is that the information, the knowledge, builds upon what you already know, what you’ve already learned. Which means that each new exhibition is enriched by what you bring to it.

I saw an exhibition at the Musée des Archives Nationales,(Fig. 1) the former Hotel de Soubise, a gorgeous hôtel particulier seized by the government in 1808 when its owners couldn’t pay their taxes. Ironically, the street on which this glorious mansion sits is rue des Franc-Bourgeois. That’s the nickname for the people who once lived here, people so poor they were not required to pay taxes, the “francs-bourgeois”.

Figure 1. Musée des Archives Nationales, former Hotel de Soubise

The exhibition I saw, ‘Louis XVI Marie-Antoinette & La Révolution, La famille royale aux Tuileries (1789 - 1792) (Fig. 2) tells the story of the French Royal Family from the moment they were forced to leave Versailles in 1789 to when they were taken to Temple prison, a (now demolished) medieval fortress. During those three years, they lived in the Tuileries Palace, a 1564 palace built under the direction of Catherine de Medici. It sat right next to the Louvre until it was destroyed by arsonists in 1871.

Figure 2. Louis XVI Y Marie-Antoinette & La Révolution …… Musée des Archives Nationales, Paris

You probably won’t be surprised when I tell you that when I traveled to France in the summer of 1989, I had two goals. One was to find a home to buy in the Dordogne. The other was to visit as many exhibitions as possible commemorating the bicentennial of the French Revolution. The most memorable for me was a wonderful exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet. Of course, there’s still lots to see and learn about the French Revolution at the Carnavalet. I remember buying some fun merch, too. Some of which I still have. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3. Bonnet Rouge, a reference to Phrygian cap worn by freed slaves in Rome (photo taken in my living room)

A few years ago, there was an exhibition called ‘Marie-Antoinette, Metamorphosis of an Image’ (Fig.4) at the Conciergerie. That structure, built as a royal residence, was transformed into a prison in 1370. Marie-Antoinette spent her final days there, before being guillotined on October 16, 1793. You can read my review of the exhibition here: Marie Antoinette at la Conciergerie. I loved it because it had almost nothing to do with M-A’s reality. And everything to do with her image. How it was manipulated during her lifetime, but mostly how it has changed, especially in popular culture, over the past 250 years.

Figure 4. Poster for Exhibition about Marie-Antoinette at Conciergerie, Paris

The exhibition now at the Archives presents a blow by blow account of the French Royal Family’s time at the Palais de Tuilleries. Using primary documents, of course, which are housed at the Archives, of course, it traces the steps and missteps, taken by Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, by their supporters and their adversaries that led, seemingly, inexorably, to Regicide. Included in the printed record of what actually happened are the scurrilous and scandalous cartoons and caricatures, the inflammatory and egregious broadsides and pamphlets that were produced to rouse the population against the royal family. (Figs 5, 6) I had already seen most of the ones about Marie-Antoinette, as they figured prominently in the Conciergerie exhibition, too. (Figs. 7, 8)

Figure 5. Some of the many scurrilous cartoons printed between 1789 - 1792

Figure 6. The Condemnation of Louis XVI

Figure 7.' La Poulle d’Autriche' (Marie-Antoinette) 1791

Figure 8. 'Ma Constitution’ (Marie-Antoinette and Lafayette) 1790-91

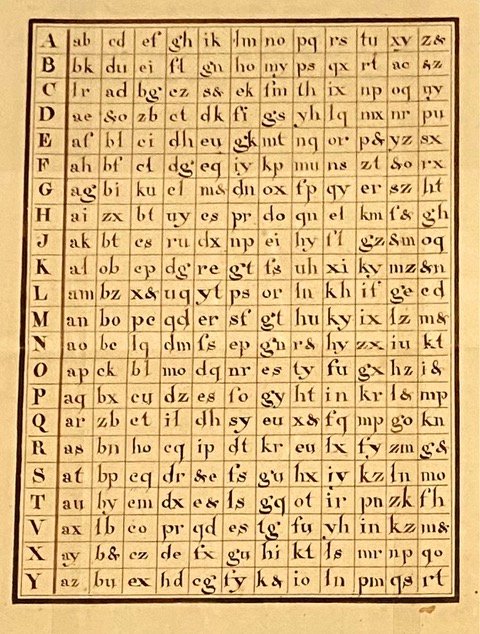

If you saw Sophia Coppola’s film Marie-Antoinette, which I cannot recommend highly enough, you know that the queen had a lover. (Fig. 9) Who never stopped trying to help his beloved and her husband and their children, escape. There are coded letters between M-A and this lover, Count Axel Fersen, a Swedish military attaché, that have been deciphered. Letters from M-A to Fersen which were not coded but whose contents Fersen protected by overwriting on them. Through the latest in modern technology, the overwriting and the text of those letters are finally being separated and the letters’ contents are now available to read for the first time. (Figs. 10, 11)

Figure 9. Count Fersen (M-A’s alleged lover) and M-A, film by Sophia Coppola

Figure 10. The Code for the letters between Fersen and Marie-Antoinette

Figure 10a. Letter decoded

Figure 11. Letters most recently deciphered using modern technology

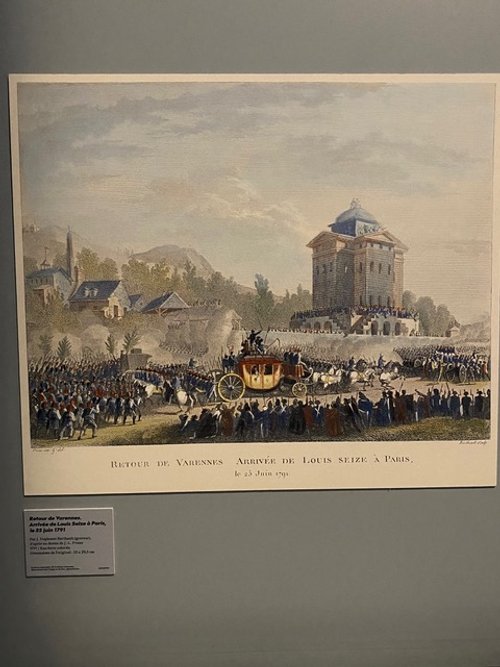

The timeline wall text records the unfolding of events that led to the ultimate conclusion of this sad story. (Fig. 11a) As I looked at it, I wanted to warn them, to tell them to pack light and try to be inconspicuous when they made their escape. But they didn’t and so they were recognized and then arrested in Varennes, (Fig. 12, Fig. 12a, Fig. 12b) just 31 miles from their destination, Montmédy, held by royalists where Louis hoped he would have greater freedom of action and greater personal security than he and his family had in Paris.

Figure 11a. Timeline

Figure 12. La Nuit de Varennes, 1982 film

Figure 12a. Timeline, 20 -25 juin 1791, Flight of Royal Family, stopped at Varennes

Figure 12b. Royal Family return to Tuileries from Varennes, June 1791

The timeline reminded me of the Van Gogh exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay which also used this device as a ticking clock, counting down the 70 days that Vincent stayed in Auvers-Sur-Oise. Before he was either shot or committed suicide in that field. For the Van Gogh exhibition, I wanted to warn Dr. Gachet (Vincent’s doctor in Auvers), Theo, (Vincent’s brother) and I desperately wanted to warn Vincent to stay away from those awful boys who teased and tormented him.

There is a second exhibition at the Museé des Archives. In the sumptuous rooms just beyond the Louis XVI exhibition. In rooms that retain their 18th century decorations - gilded carvings and mirror-glass; ceiling canvases and painted over-doors, etc. Nestled into these spaces is an installation created by the artist/ecologist, Johnny Lebigot, called ‘Nature des Fonds à dos de Giraffe.’ The grand staircase leading to both exhibitions is a foretaste of what is to come. (Fig. 13)

Figure 13. Staircase leading up to exhibitions at Musée des Archives Nationales

Lebigot works with objects he finds in nature, like feathers, leaves, flowers, branches, twigs, shells and mineral shards. He combines them (synchronizes them according to one writer) with site-specific objects, that is, objects he discovers wherever he is commissioned to stage a creation. At the Archives, it is archival boxes and book shelves as well as tables and chairs, lamps and clocks.

With his natural objects, Lebigot creates stables and mobiles, the lightest of objects hung on the most delicate of threads. They are scattered throughout the space - sometimes on tabletops and chairs, sometimes hanging high above the furniture, set next to the paneling and the paintings. (Figs. 14, 15, 16)

Figure 14. Desk with flowers and branches and twigs

Figure 15. Archive box with natural objects spilling out

Figure 16. Open desk with natural elements

“It is very important for me,” Lebigot said, “to fully integrate into the places in which I work. Above all, I'm not here to hide the decor. Whether in sumptuous hotels, in historic places or in neighborhood bars, I always try to find a discreet way to highlight the architecture, the furniture or the history of the place.”

For the National Archives, the installation cleverly capitalizes on the ‘giraffes,’ those long wooden ladders that allow access to the boxes and books stored up high. And from which the installation gets its name. (Figs. 17, 18)

Figure 17. The ‘giraffes’ used to reach books high up on shelves

Figure 18. Ladder and me in the mirror

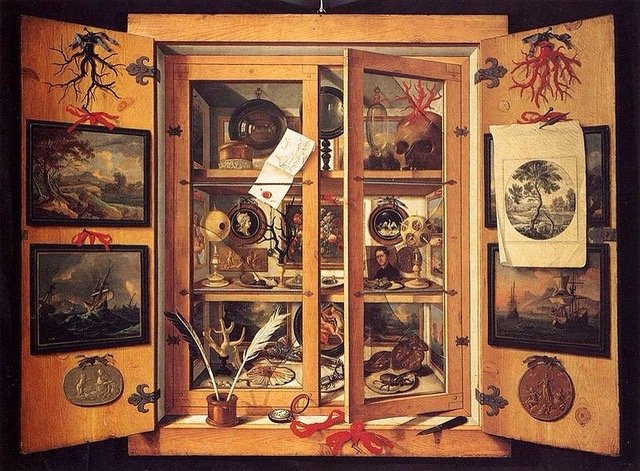

Lebigot’s installations recall the kunstkammern and wunderkammern that French and Italian and German nobility began amassing in the 16th century. (Fig. 19) Like those cabinets of curiosities, Lebigot assembles objects taken from the natural, artificial and scientific worlds and puts them together.

Figure 19. Example of a wunderkammer, filled with natural and man-made objects

The bookshelves are a marvel and maybe even a joke. Rather than tidy rows of books lined up with binding and title facing you, they have become a sort of musical notation - short, staccato beats next to long, legato ones. (Fig. 20)

Figure 20. Bookcase intervention

All of that plus the usually neat, staidly closed, archival boxes, opened here and from which spill unexpected objects waiting for your gaze. (Fig. 21)

Figure 21. Robespierre’s Desk with archive boxes and natural decoration

Lebigot’s interventions invite you to look at your surroundings differently. Even if you have visited these rooms many times, the juxtaposition and conjunctions of nature and artifice makes everything new and different.

I reviewed a temporary exhibition a year or so ago in which artists also looked to the natural world to inform and enhance the man-made one. Some of the conjunctions were celebratory, as they are here, others were ominous. Read that review here, just above Figure 9. Contemporary Artists: a dark and dirty future.

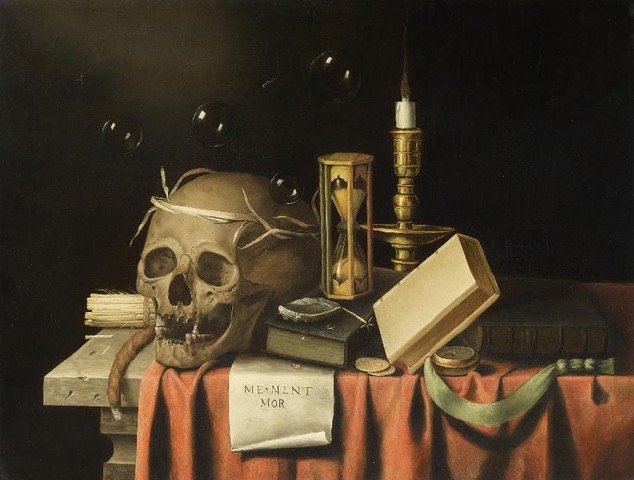

I’ll tell about one more exhibition that I saw this week, at the Fondation Cartier. (Fig. 22) An exhibition that manipulates repetition and scale to produce images that are simultaneously disturbing to look at and difficult to turn away from. The artist is the Australian born, Ron Mueck, who has worked in the US and now lives in the UK. The centerpiece of Mueck’s exhibition at the Cartier is a monumental installation called Mass, comprised of 100 giant human skulls piled on top of each other. Each time he shows this piece, he piles the skulls differently. (Figs. 23, 24) As the notes to the exhibition state, the iconography of the skull is ambiguous; associated with the brevity of human life in art history, (Fig. 25) and ubiquitous in popular culture. (Fig. 26) For Mueck, “The human skull is a complex object. A potent, graphic icon we recognize immediately. At once familiar and exotic, it repels and attracts simultaneously. It is impossible to ignore, demanding our attention at a subconscious level.”

Figure 22. Ron Mueck exhibition at Fondation Cartier

Figure 23. ‘Mass’, Skulls piled up high and scattered around, Mueck

Figure 24. The skulls seen from the garden

Figure 25. A Momento Mori, extinguished candle, sand in an hourglass & skull - al reminders of death

Figure 26. Shirt designed by Grateful Dead band for Lithuanian Basketball team

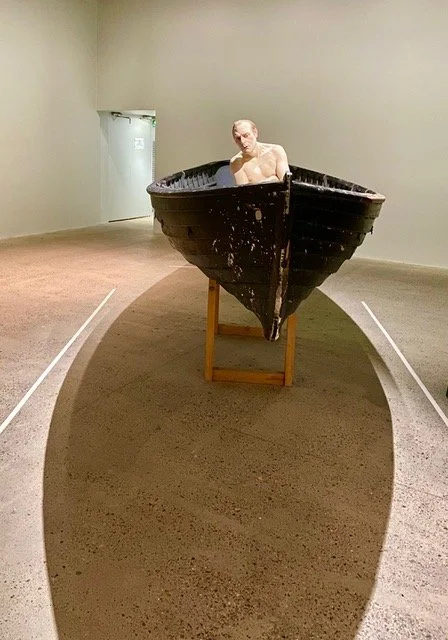

The other pieces in the exhibition, Baby, a tiny baby boy (Fig. 27) and Girl, an enormous newborn girl (Fig. 28) and Man in a Boat (Fig. 29) are completely different. In each of them, a figure is depicted in excruciating detail, a confirmation of their individuality. The artist created a new work especially for this exhibition. It’s a menacing group of three large dogs (Fig. 30) which reminded me of Cerberus, (Fig. 31) the three headed dog that guards the gates of Hades, or maybe just the billionaire who lives in a gated community near you.

Figure 27. Baby

Figure 27a. Baby, on wall to show size

Figure 28. Girl, from head

Figure 28a. Girl from other side

Figure 29. Man in a boat

Figure 30. Hounds

Figure 31. Cerberus, this one is from Harry Potter, named Fluffy

As I looked at Mueck’s Mass, I couldn’t help but think of Antony Gormley’s Critical Mass at the Musée Rodin.(Fig. 32) And Charles Ray’s exhibition a year or so ago at the Pompidou. (Fig. 33) All play with scale, all seem to ask us to question our place in the world. Not a bad idea for the times we’re living through now.

Figure 32. Critical Mass, Antony Gormley exhibition at Musée Rodin

Figure 33. The Family, Charles Ray

Thanks so much to those of you who took the time to send comments. As always they are much appreciated. Gros bisous, ‘Dr. B.’

New comment on Not really smelling like a rose.:

The relationship between Fay and Stein is so conflicting to this day in my opinion. Only the recent Malcom and Will writings have resolved it somewhat for me. Yet she and Alice were welcomed and embraced by American forces when they swept through the area of France where they were living. On another point I have always thought Alice was underrated and her writing after Gertrude's death demonstrates a lively talent in her own right. Because of all the controversies in their lives they are still so interesting and I often wonder why there hasn't been a serious movie. Diane

New comment on How to Get Your Proust On:

I’m a retired English professor (but French major at Yale), who used the pandemic lockdown to read the whole of Proust (in English translation). To my amazement, I discovered that the hero of the novel. (not Proust himself but his narrator Marcel) is a reflection of myself—my personality, interests, frustrations, and fascinations. Because of this naturally I could not stop reading. I found myself on almost every page! The novel is about self-discovery, and the vehicle for this is art. I share this viewpoint. But I am saddened by the fact that Proust, unlike myself, never experienced the satisfaction of true, lasting love. And so the long novel was surprisingly a revelation for me, showing me so much about who I am. No book in my long life of reading has done this, Jay

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.