The usual suspects

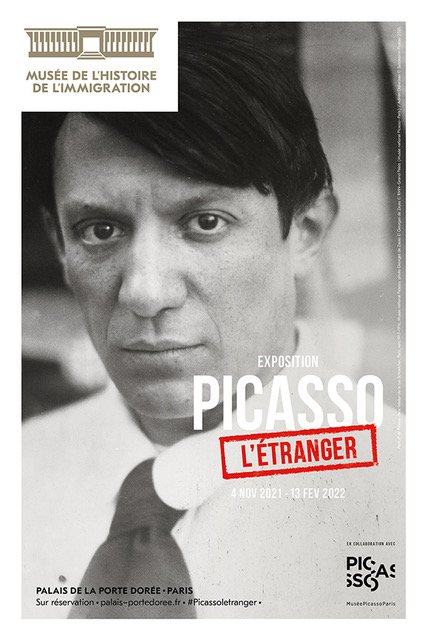

Picasso L’Étranger, Palais de la Porte Dorée

There were two major Picasso exhibitions in Paris over the summer. They’ll be on for another couple of weeks. I will tell you about them at the end of this review. Those exhibitions are a joint collaboration of the Musée Rodin and the Musée Picasso which compare and contrast the work of these two giants. My daughter made the observation that an exhibition about these two legends should include a living artist. Since neither Picasso’s nor Rodin’s heirs need another exhibition to increase the ‘value’ aka what someone is willing to pay for the work they inherited. But it could mean the difference between languishing and soaring for an up and coming artist.

Today the discussion is about yet another exhibition which considers Picasso from an entirely different perspective. The exhibition’s venue informs its focus. The Palais de la Porte Dorée, originally built for the International Exposition of 1931 (Figure 1) was conceived to celebrate France’s colonial conquests. Visitors were invited to “take a trip around the world in one day”. To discover France’s colonial possessions at pavilions inspired by native architecture, where native dancers performed and native artisans worked. With the death of France’s imperial aims, the museum got a new vision and a new name: Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration.

Figure 1. Palais de la Port Dorée, exterior with my favorite swimmer

At the inauguration of the museum in 2014, Annie Cohen-Solal, the curator of this exhibition, heard a speech during which Picasso’s name was evoked. Not Picasso the artist but Picasso the immigrant. At that moment, Cohen-Solal decided to investigate what it meant for Picasso to emigrate to France at the beginning of the 20th century. To continue to make France his home on either side of and through two world wars. With all the xenophobia and fear of foreigners. Turns out, it is a complicated story with twists and turns and lots of bureaucratic bungling.

As Cohen-Solal explains, for an artist whose work seems to have been investigated from every conceivable angle, this was one angle that had not yet been conceived. The search for clues about Picasso the Foreigner required examining ‘layers of buried documents’ in boxes that had to be opened, envelopes that had to be unfolded, handwriting that had to be deciphered and distinguished. And all of it coordinated in chronological order to tell the story.

Cohen-Solal was the perfect person for the task. She was born in Algeria and received a Ph.D. in French literature from the Sorbonne. She has taught at universities in New York, Berlin, Jerusalem and Paris, where she lives. She understands the immigrant experience because she is living it.

Her previous scholarly work includes biographies of the art dealer Leo Castelli and the artist, Mark Rothko, both of whom were immigrants in America. Both of whom succeeded in their adoptive country. A third book, called Painting American: The Rise of American Artists, Paris 1867 - New York 1948’ begins in 1867, with American disappointment at the reception of American Art at the Exposition Universelle and ends in 1948, when New York replaced Paris as the center of the art world. It’s a story of upstarts learning and then breaking the code. Much as Picasso did his entire life.

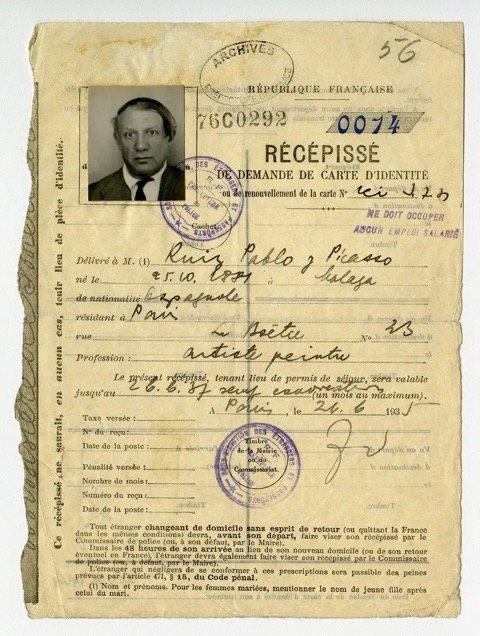

Figure 2. Dossier de la Préfecture de Police

For this exhibition Cohen-Solal plumbed two primary sources. The first, Picasso’s police file. (Figure 2) Documents that had languished in Moscow for nearly 60 years. As Alex Duval Smith noted in 2004, Picasso’s file was just one among millions of documents returned to France ‘under a post-Cold War agreement that saw seven (tractor trailers) driving to Moscow to collect a generation's worth of bureaucracy, confiscated by the Nazis in 1941 and seized by the Soviets in 1945.’ Theirs had been a long, strange trip - Paris to Berlin, Berlin to Moscow, Moscow back to Paris.

In 2001, 140 cardboard boxes filled with documents arrived at the Paris Police Prefecture, accompanied by a Russian translator. I’m not sure why the director of the archives needed a translator if the documents were in French, but never mind. One day the translator found Picasso’s signed naturalization application. The archivist and the translator determined that it was authentic. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Picasso récépissé for Demande de Carte d’Identité from 1935

They showed the Picasso file to Armand Israël, a Georges Braque expert and Pierre Daix, a friend and biographer of Picasso The book they wrote, 'Pablo Picasso: Dossiers de la Préfecture de Police 1901-1940,’' was the basis of an exhibition held in 2004 at the Musée de la Préfecture de Police (Paris Police Museum).

This is what the documents show. As early as 1901, while Picasso was still traveling back and forth from Barcelona, he was being watched. Because of his association with fellow Catalonians who lived in Paris, some of whom were or were thought to be anarchists. As Smith noted, ‘anarchists were the Islamic fundamentalists of the early twentieth century…They were watched and, as is the case today, 90 per cent of suspects were innocent. ‘ Ah, but which ones?

The men that Picasso hung out with in those early years explained Paris to him, spoke Spanish with him, made him feel less homesick. One of them was Pedro Manach, (Figure 4) who I wrote about in a review of Berthe Weill. He helped her set up her art gallery. His business sense was so much better than hers, I lamented the fact that he didn’t stay longer to help her establish her gallery. Maybe he was called back to Barcelona as Berthe Weill’s biographer suggests, maybe he was harassed by the Paris police and got out while he could.

Figure 4. Portrait of Pedro Manach, Picasso, 1901

According to Annie Cohen-Solal, there were three reasons why “Picasso was considered a suspicious person: first, he was a foreigner; second, he was considered an anarchist; and third, he was avant-garde in a country that was horrified by the avant-garde because in France the Academy of Fine Arts, the most conservative in Europe, ruled the roost.”

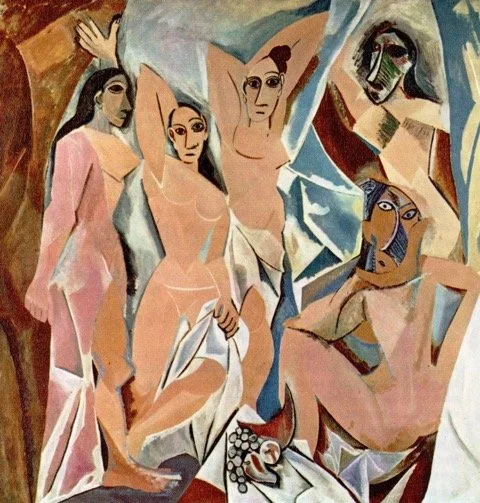

Yes, that and also … In 1911, Picasso and another foreigner, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire (born in Rome, of Polish descent) got into trouble. Four years earlier, they had acquired two Iberian heads (Figure 5) from a shady character Apollinaire knew from somewhere … The heads were of great significance for Picasso. He used them and African masks as models for his breakthrough, Demoiselles d’Avignon, of 1907, (Figure 6) the year they were stolen from the Louvre. The theft of the Mona Lisa in 1911 led to other thefts being investigated. Apollinaire was jailed briefly when he tried to return the Heads. Picasso’s courtroom appearance saved him from jail but surely didn’t endear him to his companions. In court, some sources note that he denied knowing Apollinaire.

Figure 5. Iberian Head

Figure 6. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso 1907

Picasso’s dossier continued to grow over the years. With reports sometimes no more than rumors, from a concierge who didn’t like him or from people he offended in the neighborhood. And like every other foreigner living in France, Picasso had to renew his residency card, with photos and documents, so many documents. Those of us who reapply annually for our carte de sejour are building up an impressive dossier for the French police, too. Comforting thought.

In 1918, Picasso’s dossier became even heavier. It started to include information about his Russian ballerina wife, Olga Khokhlova, (Figure 7) whom he met through Serge Diaghilev and his work with the Ballet Russes (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Olga Khokhlova, Ballet Russes

Figure 8. Set and costumes by Pablo Picasso, 1917.

In 1940, the Germans were poised to enter France. Picasso’s position was tenuous. To the French authorities, he was a suspected anarchist. The alliance between Franco’s Spain and Nazi Germany made him an enemy alien. But his 1937 painting Guernica (Figure 9) was a protest against the German bombing of that Spanish town. If he returned to Spain, he risked the same fate as Garcia Lorca who was killed by a firing squad in 1936. Picasso applied for French citizenship. Application denied.

Figure 9. Guernica, Picasso 1939

What was going on? By 1937, MoMA in New York had already held a major exhibition of Picasso’s work. He was a well known, wealthy artist. But ‘a deputy inspector general of the Police Prefecture named Émile Chevalier’ saw enough in his file to deny the artist’s application. Chevalier concluded his report: “This foreigner does not meet any of the requirements for naturalization; on the other hand, and after what has been said, he must be considered as suspicious from the national point of view.

A denied application for citizenship hung over him from 1940-1945, He could have been detained, deported. For those five years, Picasso continued to paint and wait. A Gestapo officer is said to have come to his apartment where he saw a photograph of Guernica. The officer asked Picasso if had done it. Picasso is said to have replied, ‘No, you did’.

In 2015, Ms. Cohen-Solal decided to look at the police files again. This time in conjunction with the enormous Picasso archives at the Musée Picasso in Paris. To cross reference the two sources of primary documents chronologically. And to ask some questions - like what impact did the French official attitude toward Picasso for all those years have on his work, on his relationship with France. How did the tense war years determine where and how Picasso chose to live afterwards.

Here are some other things I learned. In 1940, despite his own precarious situation, he offered to sign a letter protesting his dearest friend, Max Jacob’s (Figure 10) incarceration at Drancy, the French detention camp from which Jews were deported to Nazi extermination camps. In 1946, he helped organize a benefit auction of paintings, including his own, for Berthe Weill, the Jewish gallerist and friend of his old friend Manach, who was destitute after years of hiding during World War II.

Figure 10. Max Jacob, Picasso

Picasso exhibition, Max Jacob panel

And some other things. The first paintings by Picasso to enter French museums arrived in 1947. He donated them. In 1955 Picasso left Paris definitively for the Midi. Cohen-Solal tells us that by leaving Paris for good, Picasso chose to associate with artisans rather than academic artists; chose the countryside over the city and chose the south over the north.

This exhibition views Picasso’s personal life and professional accomplishments through the lens of the French state’s harassment of him and his always proud, sometimes arrogant, response to that harassment and his comportment afterwards. The exhibition is divided into 5 chronological sections. Works of art and film clips augment the documents from both the government and the Picasso archives. I was particularly interested in the first section. Picasso and his Mom. (Figure 11) Turns out that like Morandi, Vuillard, Andy Warhol (and my own artist son), Picasso was a Mama’s boy. Turns out, too that neither Picasso nor his mother ever threw anything away. Warhol didn’t either, he just swept each day’s detritus into a drawer. Picasso’s mother wrote to him 3 or 4 times a week until her death in 1938. He kept her letters. She kept every scrap of paper he ever touched. He further honored her by using her family’s surname rather than his father’s, PIcasso instead of Ruiz.

Figure 11. Portrait of the Artist's Mother, Picasso 1896 (Picasso was 15, his mother 41)

The exhibition contextualizes his Cubist paintings and how he and Braque explored alternative ways of depicting reality. His work with the Ballet Russes for which he supplied costumes and sets and where he found himself a ballerina wife. His anti-fascist works, like Guernica, which should have satisfied his French harassers, but didn’t. My favorite part was the final section. Picasso the ceramicist. (Figure 12) An art form he took up when he arrived in the Midi at age 70. An art form for which he showed a true gift, going from student to master. He had fled Paris to work with the artisans of the south. And he became one of them. To his pleasure and theirs. I stayed in St. Jeannet for a week last summer and visited, among other places, Antibes and Vallauris, two villages where Picasso lived and worked and where he is everywhere acknowledged. Like the chapel he decorated in Vallauris (Figure 13) and the statue of his Shepherd (Figure 14) in front of it. If you know the towns of the Midi, your appreciation for this final section of the exhibition will be enhanced. Mine was.

Figure 12. Picasso the ceramicist

Figure 13. Chapelle de la Paix", Vallauris, 1953

Picasso working on Chapelle de la Paix, photo by Edward Quinn

Figure 14. Man with a Sheep, Picasso, Vallauris

Interspersed with Picasso’s development as an artist are the French government’s repeated efforts to make amends for its treatment of Picasso. And Picasso’s responses. In 1958, Picasso was offered French citizenship. He refused it. In 1966, a huge exhibition of his work was held at the Grand Palais. (Figure 15) He did not attend it. Nor did he attend an exhibition of his work at the Louvre five years later. Even though it was the first time a living artist was so honored. In 1967, he was awarded the Legion of Honor. He didn’t accept it. That same year, Malraux, the minister for cultural affairs under Charles de Gaulle enacted a law specifically written for Picasso. Although more for his heirs than himself and ultimately more for the people of France than those heirs. The law states that an artist’s heirs can donate art work in lieu of paying inheritance taxes. Which his heirs did in 1979, which the heirs of his second wife Jacqueline did in 1990.

Figure 15. Picasso Exhibition, Grand Palais, 1966-67

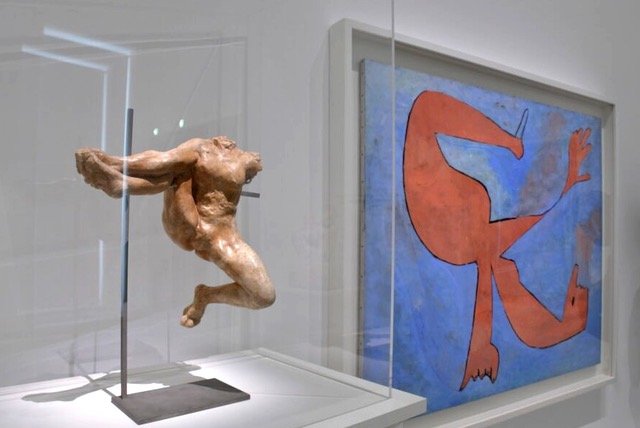

What about the two exhibitions I mentioned at the outset? The exhibitions comparing Rodin and Picasso. To confirm that Picasso was influenced by the work of his elder colleague, even if he may never have met him, we see Picasso visiting the Rodin retrospective that was held in 1900 at the Pavillon de l’Alma. And nearby is a photo of Picasso in his studio, a print of Rodin’s Thinker tacked to the wall. At the Musée Picasso, the focus is on the private sphere of artistic creation. We see both artists in their respective studios working out ideas that eventually become the works of art for which each is so well known. Picasso ‘riffs’ off his predecessor’s works, in open competition or playful acknowledgement. There is Picasso’s Kiss and Rodin’s (Fig. 16) Rodin’s Dancing Woman, a leaping figure, legs akimbo, feet omitted and Picasso’s La Nageuse, as free as the air but swimming in water. (Fig 17) Rodin’s Thinker is juxtaposed with Picasso’s Grande Baigneuse au Livre, a woman leaning on her chin, reading a book between her legs. (Fig 18) The figure of St. John by Rodin and Picasso’s Shepherd are placed next to each other. Both stride ahead toward a future only they can see. (Figs 19, 20).

Figure 16. Picasso The Kiss; Rodin The Kiss

Figure 17. Rodin, Dancing Woman; Picasso, La Nageuse

Figure 18. Picasso, The Reader; Rodin, The Thinker

Figure 19. St. John the Baptist, Rodin

Figure 20. Man with a Sheep, Picasso 1943

So, there you go. As the summary of the exhibition on the Palais de la Porte Dorée website notes, ‘(t)oday, in the midst of a global migration crisis, it appears essential, urgent, and necessary to reassess Picasso’s trajectory and work. For his odyssey as a foreigner and his agency as an artist are powerful models for our times.”

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.