Botticelli Babes

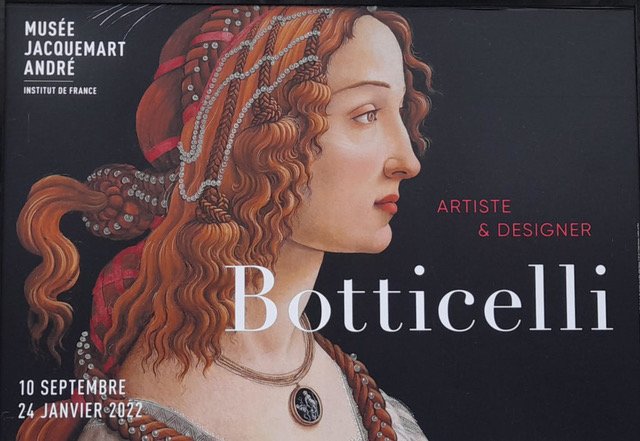

‘Botticelli: Artist and Designer’: Musée Jacquemart-André

Botticelli, whose deliciously delightful paintings we all love, is on the menu today. Specifically the exhibition I saw a few weeks ago at the Musée Jacquemart-André, called ‘Botticelli: Artist and Designer’.

First a word about his name. And a little lesson. Like Madonna, Cher and Beyonce, when we talk about the big three of the Italian Renaissance, we talk about Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael. Yes, you could call her Beyonce Knowles-Carter, but you don’t. Leonardo can be Leonardo da Vinci, (and it should have been the Leonardo Code but never mind, what’s done is done). Michelangelo is never called Buonarroti and Raphael, whose last name is Sanzio, is always just Raphael.

Botticelli is different. His birth name was Alessandro Filipepi. Sandro is simply a diminutive of Alessandro. Botticelli has nothing to do with Filipepi. It is from the word botticello (little barrel in Italian), a nickname first attached to his older brother, Giovanni. Sandro, who wasn’t round, (see self portrait in Adoration of the Magi, Figure 1) adopted it as his own surname.

Figure 1. Adoration of the Magi, Sandro Botticelli, 1475

Detail, Adoration of the Magi, Self portrait, Sandro Botticelli, (right forefront)

The organizer of the exhibition at the Jacquemart André, Ana Debenedetti, is a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Where she organized a Botticelli exhibition in 2016, ‘Botticelli Reimagined’. (Figure 2) I decided to do a little research about that exhibition to see if what she shared with her London audience was different from what she is sharing with her Paris one. Turns out it was.

Figure 2. Poster for Botticelli Reimagined ExhibitionVictoria & Albert Museum, London, 2015

The exhibition at the V & A was bigger and broader. It was divided into three sections: Botticelli in contemporary art (our contemporary, not his), Botticelli and the English Pre-Raphaelites, (mid-19th century through turn of the 20th century). And Botticelli in his own time.

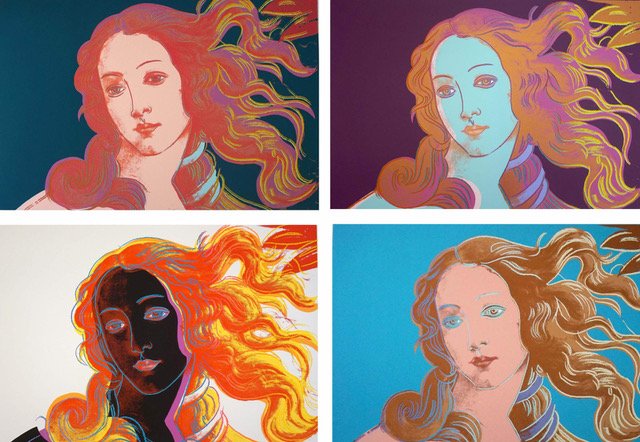

The premise of the first part, Botticelli in our time sounds interesting, even a little provocative. How are the masterpieces with which we associate Botticelli like the Primavera (Figure 3) and Birth of Venus (Figure 4) incorporated into the arts of today - from painting and prints (Figure 5) to fashion (Figure 6) and film. I like this sort of thing - riffs, juxtapositions, appropriations. The critics were mostly unimpressed. Maybe camp veered too close to kitsch for them. But it is a valid question - how are masterpieces from the past referenced in the art and design of today. And does it mean anything. Does it tell us anything about ourselves? Do you remember when Jeff Koons designed a series of purses for Louis Vuitton? Classic Vuitton purses decorated with details from paintings by icons like Leonardo (who Koons being Koons, called Da Vinci) Fragonard, Van Gogh. (Figure 7) Who Koons identified by name on the bags. Of course the critics criticized him. But I think he introduced these paintings to some people. Maybe even some people who could afford a Vuitton bag. Now that’s a public service!

Figure 3. Primavera, Sandro Botticelli, 1477-82

Figure 4. Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, 1484-86

Figure 5. Warhol Birth of Venus, Andy Warhol, Screenprint, 1984

Figure 6. Left: Botticelli dress by Dolce & Gabbana; Right: Rebirth of Venus, David LaChapelle, photo, 2009

Figure 7. Louis Vuitton handbags, collaboration with Jeff Koons, 2017

Botticelli’s paintings are so well known now that we can’t imagine a time when that wasn’t the case. But between his death in 1510 and the mid-1800s, that is, for nearly 350 years, he was largely forgotten. It was the naturalism of Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo, their ability to render three dimensional space on a two dimensional surface that was the measure of excellence. Works by earlier artists like Botticelli looked primitive by comparison, and that’s what those artists were called, “Primitives”.

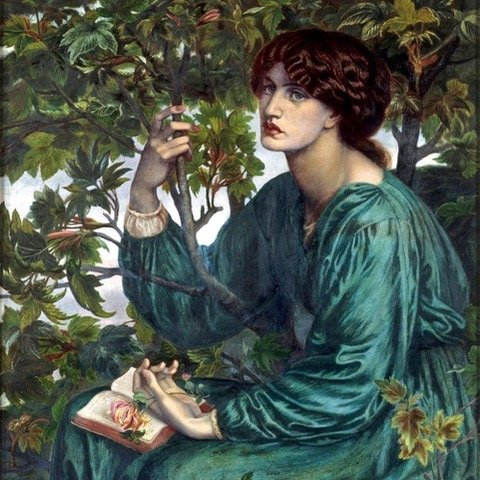

The rediscovery of Botticelli in the second half of the 19th century is the second section of the exhibition at the V & A. The artists who championed Botticelli came to be know as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. They were young artists at odds with academic art which privileged art of the High Renaissance. These young artists were inspired by the exuberant, intricate, colorful compositions of the artists who worked just before Raphael. Ergo the name, Pre-Raphaelites.

The Pre-Raphaelites didn’t do what today’s artists and designers do. They didn’t reproduce Renaissance masterpieces on pantsuits and purses. They were influenced by the paintings, but they made them their own. From William Morris to Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, (Figure 8) their search was for the essence of Botticelli.

Figure 8. La Ghirlandata, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1878

The V & A has one Botticelli in its permanent collection, a portrait of Smeralda Bandinelli. (Figure 9) This is how that painting came to the V & A. Dante-Gabriel Rossetti bought it at auction in 1867 for £20. His own portrait of Jane Morris from 1879 called ‘The Day Dream’ (Figure 10) was based upon it. Rossetti’s painting was commissioned by the Greek collector Constantine Ionides. Who paid Rossetti £735 for his painting and £315 for Rossetti’s Botticelli. Ionides eventually donated his painting collection to the V & A.

Figure 9. Smeralda Bandinelli, Sandro Botticelli, 1470-75

Figure 10. Portrait of Jane Morris called ‘The Day Dream’ Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1879

Twenty years later, in 1899, Isabella Stewart Gardner paid the Italian Prince Chigi $70,000 for his Madonna and Child. The price escalation confirms the increase in Botticelli’s perceived worth. The Chigi Madonna and Child (Figure 11) is a beautiful painting filled with symbolism (as all paintings of the Madonna and Child are). The enclosed garden, for example, is a reference to the Madonna’s virginity. The elegant angel wears a myrtle crown, another symbol of her virginity. (FYI: myrtle isn’t always a symbol of virginity, In Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, for example, the nymph who holds the cloak for Venus, wears a myrtle sprig necklace. Here myrtle is a symbol of love and fertility). In the Chigi Madonna, the angel holds a bowl filled with grapes and wheat. References to the blood and body of Christ, the Eucharist. The Virgin holds a sheaf of wheat, an allusion to her acceptance of her Son’s sacrifice. Prefiguration is what that’s called. Through gesture or expression the Virgin signals that she knows that too soon, she will be holding the dead body of her son in her lap. The Christ Child raises his fingers in benediction. The swaddling cloth around his middle is another symbol of his fate, it alludes to the winding cloth of death.

Figure 11. Chigi Madonna, Sandro Botticelli, 1470

It wasn’t only artists and art patrons who discovered Botticelli in the second half of the 19th century. As the railways reached Florence, English and European middle class travelers, not just people going by private coach on grand tour, could travel to Florence and see Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and the Primavera at the Uffizi. Of course, while in Florence, many suffered from Stendhal or Florence Syndrome, a condition caused by seeing too many beautiful things in such a beautiful setting. Symptoms included rapid heartbeat, fainting, even hallucinations. (Figure 12) Worth it, right?

Figure 12. Young woman experiencring Stendhal Syndrome

The third section of the exhibition at the V & A was Botticelli in his own time, the precedent for the current show at the Jacquemart-André. Which is itself a perfect venue for the exhibition since there are two Botticellis here. An early Madonna and Child (Figure 13) which shows a nicely formed, compact, standing Christ Child, his fingers raised in benediction. A delicate teenaged Mary, has her hand on His elbow, holding him up. The other painting is an unusual Flight into Egypt. (Figure 14) Instead of the Virgin seated on the donkey, she is walking alongside it. The donkey gazes sheepishly up at us. He knows he is getting away with something. The Virgin’s robes are gorgeous, moss green, pink from pale to intense and royal blue. Neither Joseph nor the Christ Child have necks (genetic?, oh no wait, can’t be that). And both are showing a lot of leg.

Figure 13. Madonna and Child, Sandro Botticelli, 1470s

Figure 14. Flight into Egypt, Sandro Botticelli

The V & A and the J-A exhibitions were both curated by Ana Debenedetti, an Italian Renaissance specialist. According to her, the J-A exhibition explores “the idea of the artist as designer” and considers his studio as a “laboratory of ideas”.

When I came to see this exhibition, I thought I already knew quite a lot about Botticelli. I knew his two most famous paintings, of course, just like you do. And their iconography (don’t worry, I’ll spare you). And while neither of those paintings ever leaves Florence, there were a couple very shapely, very leggy Venus Pudica (Venuses who modestly cover their private parts) (Figure 15) here to remind us of their sisters. I am familiar with Botticelli’s religious paintings and his mythologies. I know his portraits, many of which are of the Medici. (Figure 16) I know about his obsession with Simonetta Vespucci. (Figure 17) I also know that in the late 1490s, he came under the influence of the fanatic Dominican friar, Savonarola. (Figure 18) But I had always thought of Botticelli as a lone genius who created idiosyncratic paintings before succumbing to the teachings of Savonarola. Turns out the Savonarola part is mostly true but the lone genius part, not so much.

Figure 15.Venus Pudica, Sandro Botticelli (poses like Birth of Venus, Figure 4 above)

Detail, figure 15

Figure 16. Portrait of Guiliano de Medici, Sandro Botticelli, 1478-1485

Figure 17. Idealized portrait of Simonetta Vespucci, Sandro Botticelli, 1480-85

Figure 18. Savonarola, Fra Bartolomeo c. 1498,

The exhibition presents Botticelli’s career chronologically and thematically beginning with his own apprenticeship in the studio of Filippo Lippi before moving on to Botticelli’s own increasingly busy studio. Filled with apprentices and assistants and eventually associates, among them Lippi’s son, Filippino. Botticelli’s studio is described as a laboratory where Botticelli was not only creator but also entrepreneur and mentor. He simultaneously worked on dozens of projects and supervised a workshop filled with artists at different stages of their careers. A workshop in which students assisted and assistants painted large sections of works that left the studio with Botticelli’s signature.

And of course, it only makes sense. For example, there are just too many surviving tondos (tondi, circular paintings) of the Madonna and Child, (Figure 19) to have been painted by one person. Botticelli designed a few master compositions from which associates made copies in different colors with a variety of accessories.

Figure 19. One of MANY Tondo (usually Madonna & Child with Angels), Sandro Botticelli

In fact, one of the contributors to the exhibition’s catalogue wrote a doctoral dissertation on one of Botticelli’s assistants, the one who always painted gothic architecture in the background. The assistant, formerly called Master of Gothic Architecture now has a name, Jacopo Foschi. And he has been credited with painting the predella, (lower panel), of the Coronation of the Virgin (1492) (Figures 20) which was lent by the Bass Museum of Miami. And here it is, reunited with its predella for the first time in a long time. As Debenedetti notes,“Here we have a hugely prestigious work, but Botticelli doesn’t hesitate to ask an assistant to do the entire predella,”

Figure 20. Coronation of the Virgin, Sandro Botticelli, 1492

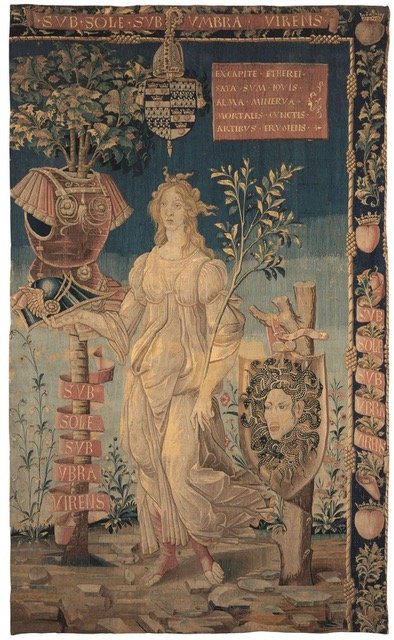

The exhibition also traces how Botticelli creatively repurposed designs originally intended for paintings to be used on other materials, such as tapestries (wall hanging) embroideries (furniture covering) and marquetry (wood work). (Figure 21)

Figure 21 Peaceful Minerva, wool & silk tapestry, French manuf. after Sandro Botticelli, 1491-1500

Botticelli’s connection to the Medici, the ruling family of Florence lasted nearly 40 years, until they were ousted by Savonarola. Through the Medici, he received lots of commissions. One of which was to produce nearly 100 large illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy. (Figure 22) This was the beginning of modern, secular book illustration according to the art historian, Simon Wilson.

Figure 22. Dante’s Inferno, illustration of Canto XVIII,.One of 4 fully colored pages, Sandro Botticelli

The end of Botticelli’s career coincided with the dramatic arrival and subsequent execution of Savonarola, the Dominican friar who preached in and around Florence starting in the early 1480s. Initially welcomed by the Medici, when Savonarola began preaching against the exploitation of the poor and the tyrannical abuse of power, things went downhill rapidly for the Medici. They were overthrown in 1494. With the Medici gone, Savonarola became the de facto ruler. He was doing alright with the Florentines but since his sermons also included the denunciation of clerical corruption, the Pope and hierarchy of the Catholic Church decided he had to go. Unable to silence him, after the bonfire of the vanities in 1497, Savonarola was arrested then hanged and burned at the stake in the central square of Florence. (Figure 23) So much for trying to stand up for the downtrodden.

Figure 23. Savonarola burned on the cross at the stake, 1498

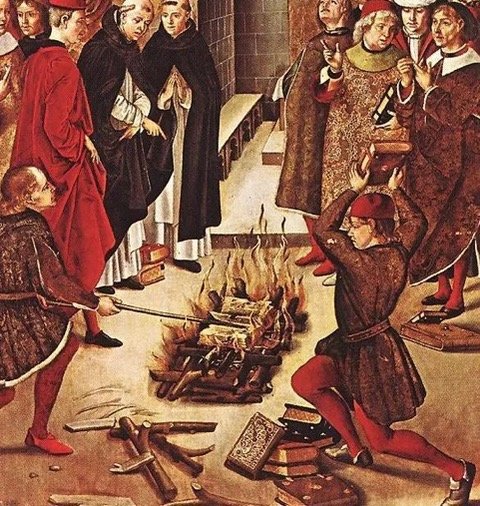

According to one source, Savonarola’s rule of Florence was fatal for Botticelli’s business which completely dried up in 1500. And the artist died, nearly penniless ten years later, in 1510. Another source contends that Botticelli became a fervent believer in the friar’s teachings. That he destroyed many of his own secular paintings during the above mentioned bonfire of the vanities when Savonarola encouraged his followers to destroy anything they owned that could be considered a luxury - from books to silks, musical instruments to manuscripts. (Figure 24)

Figure 24. Bonfire of the Vanities, Florence, 1497

A comparison of two depictions of the same subject, one from early in his career and one from the end of it, that is, one pre and one post Savonarola, shows the effect of the friar’s teachings on Botticelli’s art, maybe too, his sensibility. The subject is Judith and Holofernes. The pious Hebrew widow who seduced and then beheaded the commander of the Assyrian arm. And saved her people from defeat. The subject resonated in Renaissance Florence. Judith, like the Old Testament hero David was a symbol of the city, small, but valiant and ultimately triumphant over much bigger and stronger adversaries, Holofernes and Goliath. Alternatively Judith could serve as a model for women, her piety, her bravery.

Botticelli’s early version, from 1470, (Figure 25) shows a young, beautiful blond Judith, in a billowing frock of blue and white and gold, gracefully holding a not-bloody sword. She glides along with her equally lovely maid, dressed in a soft sherbet orange robe, balancing the serene severed head of Holofernes in a bowl, on her head.

Figure 25. Judith returning from Holofernes tent, Sandro Botticelli, 1470

Thirty years later, Botticelli depicted the same Old Testament tale. (Figure 26) Now Judith, looking a little shell shocked, is shown leaving Holofernes’ tent, holding up the severed head in one hand and the sword she had just used to behead the enemy commander, in the other. She is dressed in somber burnt oranges, moss greens and metallic grays. Her maidservant is seen from the back, much smaller than Judith, dressed completely in gray. The head of Holofernes is very small compared to Judith’s. The background is bare and it is all blackness inside the tent.

Figure 26. Judith with the head of Holofernes, Sandro Botticelli, 1500

The exhibition presents Botticelli in a new way, as a genius of organization and management. Botticelli’s mastery was not limited to the paintings he created alone but includes those he oversaw being painted in the workshop he managed. Such dual roles, the curators of this exhibition want us to know, were typical of artists in Italy during the Renaissance.

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you