The Big Reveal: What art historians do all day

Giovanni Bellini: Influences croisées (Musée Jacquemart-Andre); Antoine Caron: Le théâtre de l’histoire (Chateau d’Écouen)

I recently saw two exhibitions, at two beautiful venues about two significant Renaissance artists - one Italian, one French. At the Musée Jacquemart-André, the exhibition is on the Venetian Renaissance master, Giovanni Bellini, (ca 1435-1516). Exhibitions at the J-A are always accompanied by an excellent video. In this video, the curator tells us that most Bellini exhibitions have focused on the artist’s work in isolation. In the context of his individual artistic development. This exhibition is different, it establishes links between Bellini and the artists he was influenced by and those he influenced, a much better way, we are assured, to understand Bellini.

The French artist Antoine Caron’s multifaceted career is the subject of an exhibition at the Chateau d’Ecoeun. Caron was well known in his own time, almost completely unknown in ours. The Renaissance arrived in France very late, imported from Italy by Francois I when he recruited Italian artists to paint at his court. Caron began as a pupil of these Italian artists, continued as their colleague and concluded as their successor in what is called the Fontainebleau School of Art.

We’ll start with Giovanni Bellini, the illegitimate son of the painter Jacopo Bellini, in whose home he was raised, with his half-brothers and half-sisters.

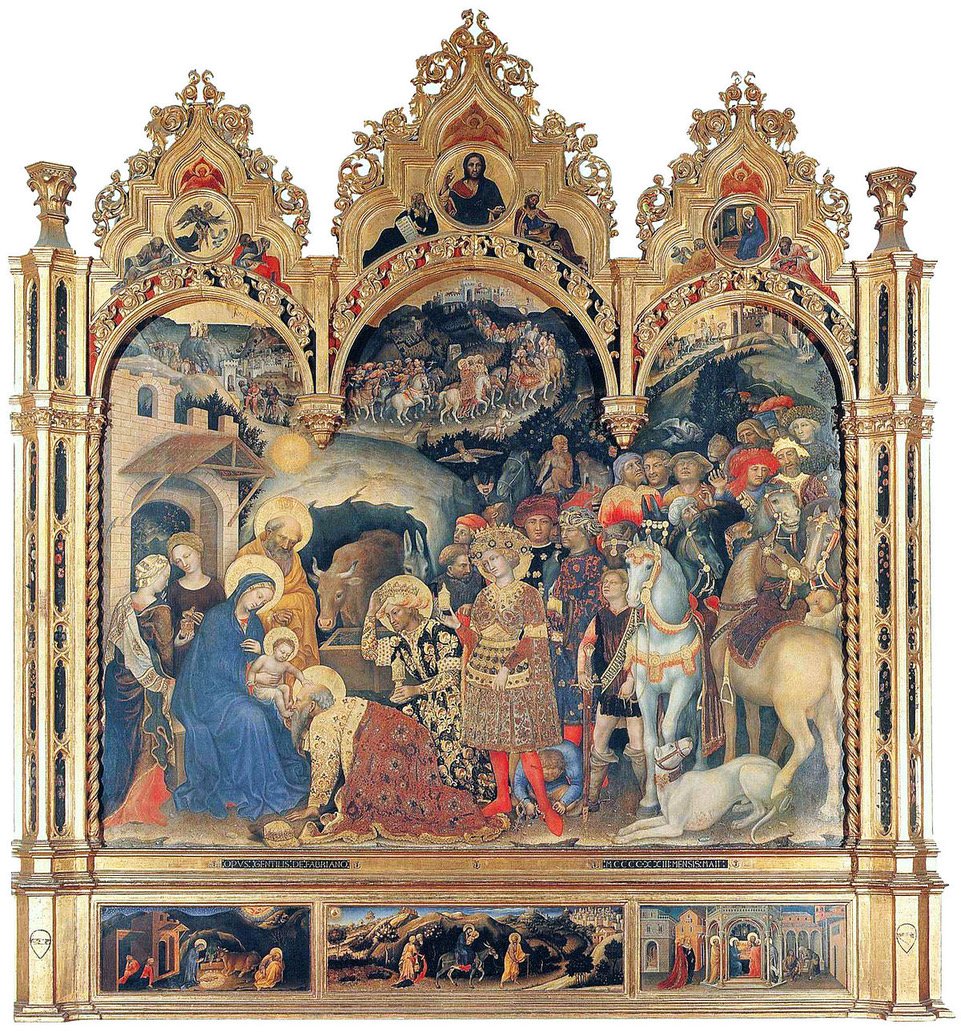

Jacopo Bellini (1400-1470) (Figure 1) painted in the ‘International Gothic Style’ which he learned from the most renown master of that style, Gentile da Fabriano (1370-1427). (Figure 2) And for whom Jacopo had such admiration that he named a son after him. Giovanni and his brother, Gentile were apprentices in their father’s studio, where they received a traditional education. Mostly copying their father’s works. In fact, through the mid-1450s, it is often impossible to determine which Bellini painted what. (Figures 3, 4) The first room in the exhibition is called ‘In Jacopo’s Studio’.

Figure 1. Madonna and Child adored by Prince d’Este, Jacopo Bellini

Figure 2. Adoration of the Magi, Gentile de Fabriano

Figure 3. Gentile & Giovanni Bellini, Birth of the Virgin

Figure 4. Madonna & Child with Saints below, Jacopo & Gentile Bellini

Then the fun begins. The second room is called Paduan Models. Here we learn about the role Jacopo’s son-in-law played in Giovanni Bellini’s artistic development. And who was that? Andrea Mantegna! One of the superstars of Italian 15th century painting. Whose most famous paintings (according to me) are his frescoes still in situ at the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua. (Figure 5) Even as early as 1453, when Mantegna was only 22 and Jacopo agreed to let him marry his daughter, Mantegna was fascinated with classical antiquity. Roman sculpture and architecture fill the backgrounds of his mythological scenes as well as his religious ones. (Figure 6) He was equally obsessed with perspective. (Figure 7) Many of his works show breathtaking manipulations of it. Both Mantegna and Bellini were influenced by the Florentine sculptor, Donatello. Who had lived in nearby Padua in the decade before Mantegna arrived and whose monumental equestrian statue of the mercenary, Gattamalata, (Figs 8, 9) both young painters surely knew.

Figure 5. Camera degli Sposi (ceiling of the room of the newly weds) Palazzo Ducale, Mantua, Andrea Mantegna

Figure 6. Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, Andrea Mantegna

Figure 7. Dead Christ & Three Mourners, Andrea Mantegna

Figure 8. Gattamalata, Donatello

Figure 9. Dead Christ with Angels and Mourners, Donatello

After Mantegna left Venice for Mantua, Giovanni began to specialize in paintings of the Virgin and Child. (Figs 10, 11) They were mostly private paintings commissioned by individual patrons. Which permitted Giovanni to repeat the subject with little variation, over and over again. When talking about images of the Virgin and Child, it is difficult to ignore the importance of Byzantine art for Giovanni. The next room doesn’t, it’s called, ‘Byzantine reminiscences’. (Figs 12, 13) When Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, refugees fled to Venice, carrying manuscripts, icons and relics. Gold backgrounds began to appear in Bellini’s Madonna and Child paintings.

Figure 10. Madonna & Child, Giovanni Bellini

Figure 11. Madonna & Child with two Saints, Giovanni Bellini

Figure 12. Madonna & Child, Byzantine painting

Figure 13. Madonna & Child, gold background, Giovanni Bellini

The pendulum swung the other way, too, when Giovanni learned about the oil paintings by Flemish and Netherlandish painters like Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling. (Figs. 14, 15) Paintings with a level of realism and detail that Italian paintings, in tempera simply could not achieve. Bellini drew inspiration from such works, without fully understanding the technique. And then Antonello da Messina arrived. It was 1475, he stayed for a year. Antonello was born in Sicily, studied painting in Naples and paintings by Netherlandish and Flemish artists, there, too.(Fig. 16) When Antonello traveled to Milan, he befriended van Eyck’s student, Petrus Christus. (Fig. 17) Here is the exchange they made: Antonello taught Christus about linear perspective and Christus taught Antonello about oil painting. Giovanni’s and Antonello’s encounter in Venice also led to exchanges of ideas and techniques. Alas, Antonello left Venice after a year and Bellini was on his own again.

Figure 14. Madonna & Child with Saints and priest, Jan van Eyck

Figure 15. Madonna & Child with angels, Hans Memling

Figure 16. Dead Christ with Angels, Antonello da Messina

Figure 17. Couple at Jewelers, Petrus Christus

One section is devoted to Giovanni’s devotional images and individual portraits. And how they changed in the 1480s. To arouse viewer empathy, Bellini began to portray Christ as the interlocutor rather than as a distant figure. (Fig. 18) That’s a clear reference to Andrea Mantegna’s Ecce Homo which shows Christ close-up and suffering. (Fig. 19)

Figure 18. Christ with two Angels, Giovanni Bellini

Figure 19. Ecce Homo, Andre Mantegna

Another section of the exhibition is devoted to landscapes, which begin to pop up in the backgrounds of Giovanni’s Madonna and Child paintings and his Crucifixions. Initially the references are to Flemish paintings and Mantegna. Then they are references to one of Giovanni’s students, Cima da Conegliano (1459-1517) who both imitated his master’s work and was a source of inspiration for it. (Figs. 20, 21)

Figure 20. Crucifixion, Cima da Conegliano

Figure 21. Madonna & Child, Giovanni Bellini

Bellini had other students, among them the superstars of Venetian High Renaissance art - Giorgione (1477-1510) and Titian (c. 1488-1576). Learning Leonardo’s (Figure 22) sfumato technique, their landscapes are hazy, atmospheric. What we call ‘Colore’ and what defines Venetian painting. (Figs. 23, 24)

Figure 22. Virgin & Chid with Ste. Anne, Leonardo da Vinci

Figure 23. The Storm, Giorgione

Figure 24. Madonna & Child, Titian

The final section is called, Twilight of the Gods. One of Bellini’s last paintings, Mocking of Noah shows the old man naked and sleeping, (Fig. 25) being mocked by his sons. One art historian has called this canvas, the first modern painting. This exhibition is what an art history exhibition should be. You really must see it.

Figure 25. Mocking of Noah, Giovanni Bellini

And now we’re off to the lovely Chateau d’Ecouen which is worth a visit even if this exhibition about an artist whose name will probably be unfamiliar to you, Antoine Caron (1521-1599) wasn’t here. Caron was a versatile artist who created designs for engravings, tapestries and royal entries, as well as the occasional canvas. (Fig. 26)

Figure 26. Antoine Caron

Caron was born in Beauvais, but that’s all we know about his early life. We don’t know how he came to be a painter, where or with whom he studied. There are simply no surviving documents, at least none that have been discovered. He is first mentioned in the 1540s, when he was in his early 20s, working at the Château de Fontainebleau, with Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio. (Figs. 27, 28)These two Italian artists came to France to work for François I. Indeed it was under François I, who ruled from 1515-1547, that Renaissance art and architecture first appeared in France. It was François I, as you’ll remember who invited Leonardo da Vinci to live in Amboise.(Fig.29)

Figure 27. Descent from the Cross, Rosso Fiorentino

Figure 28. Ulysses and the Sirens, Francesco Primaticcio

Figure 29. Death of Leonardo in the arms of Francois I, J-A D. Ingres

When Fiorentino and Primaticcio came to France to decorate the Chateau de Fontainebleau, they brought the Italian Renaissance with them. Not the proto-renaissance which had been replaced by the early Renaissance which itself had been succeeded by the high renaissance. Rosso and Primaticcio were masters of what happened after the high renaissance, Mannerism. A style of painting created by artists who knew all the rules of perspective and were bored by them. Who knew how to render fabric so that it appeared to be fur or velvet or linen, and were bored of that, too.

Mannerism fit in perfect with life at François I’s court, it was effete, it was sophisticated. Working with a stable of Italian and French artists, Rosso and Primaticcio and Niccolò delle’Abbate after Rosso committed suicide in 1540, created the French version of Mannerism. For the Chateau de Fontainebleau, mythological and allegorical scenes were combined with intricate stucco ornament. Figures with long limbs and sharply defined, elegant profiles. They recall both late Michelangelo and all of Parmigianino. (Figs. 30, 31) The stucco work was both figurative and decorative, with swags, cartouches and above all strap-work. Strap-work was invented here. It’s stucco cut into long strips, that are rolled at the ends and then intertwined to create fantastic shapes. (Fig. 32) Most of the decorations created at Fontainebleau have disappeared, victims of changing taste. The Gallery of Francis I survives. (Fig. 33) Caron’s work on the decorations of the Gallery of Ulysses was destroyed in 1738.

Figure 30. Entombment (unfinished) Michelangelo

Figure 31. Madonna with the Long Neck, Parmigianino

Figure 32. Ceiling of Chateau de Fontainebleau, strap work

Figure 33. Gallery of François I, Chateau de Fontainebleau

After François I’s death, his daughter-in-law Catherine de Medici, (whose made for the movies life included being the wife of one king (Henri II) and the mother of three others), took over as art director. Among the painters she employed was Antoine Caron. He provided the designs (cartoons) for the Valois Tapestries. While scholars don’t know if Catherine commissioned the tapestries or not, they were hers by 1589 when she gave them to her granddaughter who became the wife of Ferdinando I, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The tapestries have been in Florence ever since, rarely displayed and never together. In the early 2000s, thanks to a gift from a group of Americans in Palm Beach, Florida, the tapestries were cleaned and repaired. And immediately sent off to the United States, well 6 of them anyhow, for an exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art (perhaps the summer home of those Florida snowbirds).

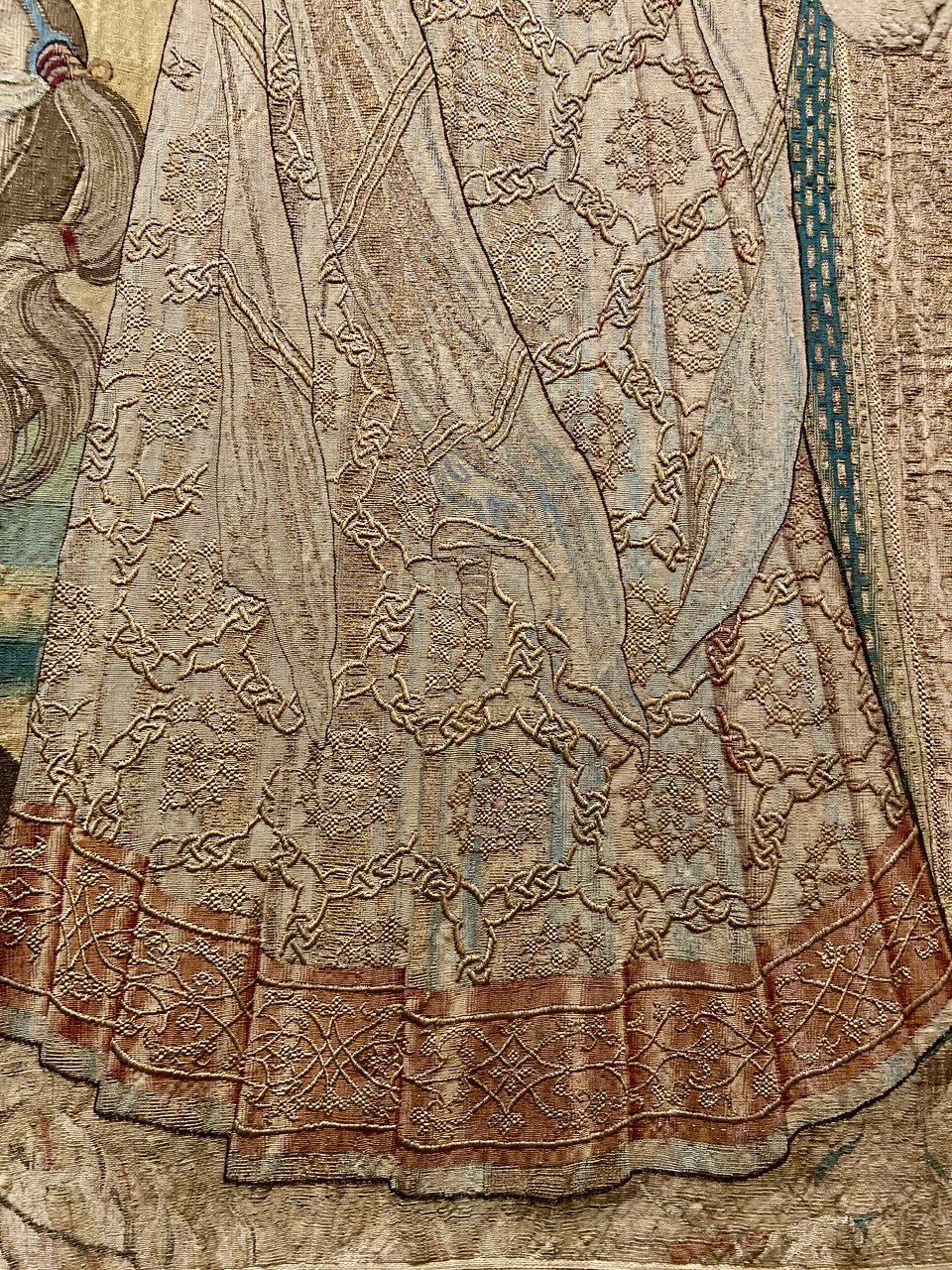

For the exhibition at the Chateau d’Ecouen , all eight tapestries are on display. They are based on 6 (maybe 8) designs by Antoine Caron. Surrounded by borders, probably the handiwork of artists connected to the tapestry makers, each of the tapestries has two distinct parts. Caron designed the busy backgrounds. The foreground figures, portraits of the French royal circle and their guests, are the work of a second artist. Some of the entertainments depicted on the tapestries can be linked with specific events, like festivals held at Fontainebleau and Bayonne and a ball held for the Polish ambassadors at the Tuileries. (Figs. 34, 35, 36, 37)

Figure 34. Valois Tapestry after design by Antoine Caron

Figure 35. Valois Tapestry after design by Antoine Caron

Figure 36. Valois Tapestry, detail after design by Antoine Caron

Figure 37. Valois Tapestry, detail dress, after design by Antoine Caron

By 1580 when the tapestries were being designed, Antoine Caron had already created ephemeral displays for the 1561 triumphal entry of Charles IX into Paris and the entry of Henri de Valois into Paris in 1573 when he became king of Poland.

Since medieval times, following a coronation in Reims, the king of France was welcomed into Paris by a royal entry, through the Porte Saint-Denis. Royal entries served a twofold purpose. They proclaimed the loyalty of the king’s subjects. They also reminded the king that their loyalty was contingent upon his concern for their well-being. The 1561 royal entry was initially postponed and eventually canceled because of the civil unrest rocking the country (Wars of Religion) Although no specific drawings can be linked to the canceled festivities, scholars are sure that the decorations were saved and used for a later event, during a calmer moment.

Catherine considered these entertainments worth the expense. Which is good since they were very expensive. They showed both foreign courts and people at home, that the Valois monarchy was as magnificent as ever. And the martial sports and tournaments held during the festivities kept feuding noblemen from fighting with each other. Indeed the same reason Louis XIV had the Chateau of Versailles built.

Finally Queen Esther, who I always seem to be bumping into. In 1560, Caron was commissioned by a Parisian printmaker to provide 6 designs for a History of Esther and Ahasuerus. A drawing by Caron and two prints (one in black and white, the other in color) are on display here and provoke the following question. How is it that drawing and print are identical and not mirror images? The only answer is that there was an intermediary print which the printmaker used so that his engraving could be identical to Caron’s drawing. (Figs. 38, 39) Like the tapestry of Queen Esther at the Chateau de Roche Guyon, this one was probably created as a plea for religious tolerance. No, not for the Jews but for the Protestants in Catholic France during the Wars of Religion.

Figure 38. The Coronation of Esther, Antoine Caron design

Figure 39. Crowning of Queen Esther after design by Antoine Caron

The Chateau d’Ecouen is out of Paris but an easy day trip on the RER.

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.