Mondrians and Madeleines

Yves Saint Laurent aux Musées

In one week, I visited 6 museums to see 1 exhibition. All celebrating the 60th anniversary of Yves Saint Laurent’s first haute couture collection in 1962. I visited two museums each day, for practical rather than thematic or aesthetic reasons. First day, I walked over to the Centre Pompidou and the Musée Picasso, both easy walks from my flat and each other. The second day, a quick metro ride to the Yves Saint Laurent Fondation and the Musée de l’art Moderne, only 4 minutes apart, the first of which has the elegant hush of a hotel particulier, the second of which has breathtaking views of the Eiffel Tower. And finally, the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay, a short metro ride to the first and then a quick walk across the Seine to the second. Though not ideal on a windy day, which it was the day I went. The exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay prompted an impromptu return to the Musée Carnavalet to see the current exhibition on Proust. The Carnavalet is just a stone’s throw from the Place de Vosges, one of my favorite haunts. Museum hopping is a fabulous way to experience Paris.

There are so many things we could discuss about these exhibitions but since arts longa, vita breves (art is long, life is short) we are going to concentrate on these: Is fashion art. What and how did paintings inspire Yves Saint Laurent. And Proust.

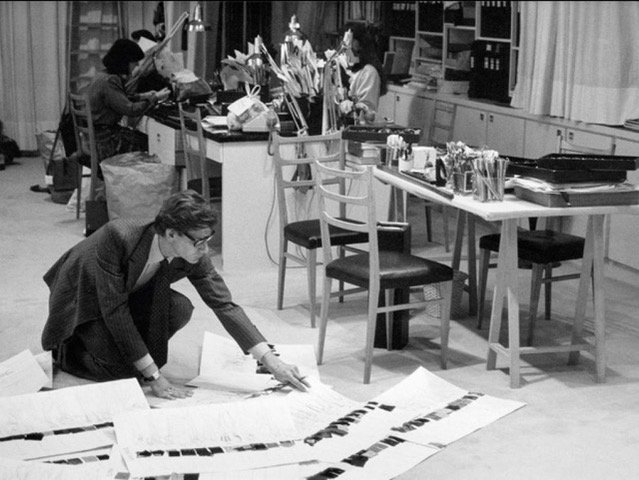

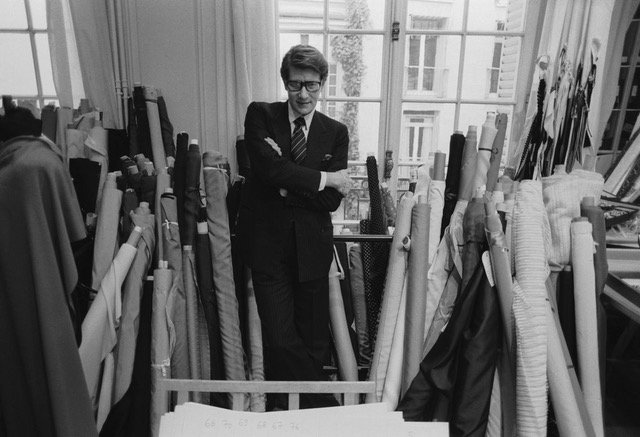

But before we get started, a quick primer on haute couture. Briefly, and not completely, an haute couture designer must present a collection of at least 50 original designs to the public every fashion season. (Figure 1) That is, 50 designs each January for the Spring/Summer collection and 50 designs each July for Autumn/Winter collection. Day and evening apparel. Yves Saint Laurent’s collections often had many more pieces. Two additional requirements - an atelier in Paris with a minimum of 20 full-time employees. At Saint Laurent’s Paris atelier he employed over 200 full-time employees. (Figure 2)

Figure 1. Yves Saint Laurent fashion show featuring Matisse,1981

Figure 2. Yves Saint Laurent at work in Atelier

Figure 2a. Yves Saint Laurent in Atelier

Can you imagine what it must be like to create an entire collection, a new and fresh collection, twice a year. And then go from initial concept to final design in 6 months, only to repeat the process again immediately after one collection is out the door and on the runway. (Figure 3) And what about shoes and hats and jewelry and make-up. And finding photographers for photo shoots and venues for fashion shows. That was Yves Saint Laurent’s life, year after year, for forty years. And that was not all of course, there was his pret-a-porter line (begun in 1966) and his made to order wedding dresses and his costumes for films and special events. And his perfumes.

Figure 3. Yves Saint Laurent with model

Figure 3a. Yves Saint Laurent chosing fabric

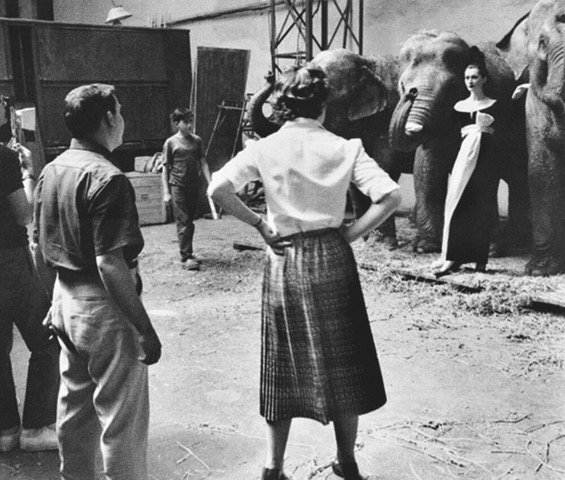

Here’s a little Yves Saint Laurent bio. He was born in French Algeria in 1936. The older brother of two sisters who all grew up in a happy family in a villa by the Mediterranean sea. His interest in dress designing started very young. Before he left home for design school in Paris at 17, he was designing clothes for his mother and sisters. Two years after he got to Paris, he was working for Christian Dior. That same year, when Saint Laurent was still an assistant at the House of Dior, he designed a long sleeved black evening gown with a long sash of white taffeta that cinched the model’s waist and trailed to the ground. Richard Avedon, the photographer for Harper’s Bazaar photographed the model, Dovima, in that dress, at the Cirque d’Hiver, her arms outstretched, an elephant at either side. (Figures 4, 5, 6) Avedon remembered, “I saw the elephants… . I then had to find the right dress … I knew there was a potential here for a kind of dream image.” He was right. The photo is iconic. So is the dress.

Figure 4. Photograph for Harper’s Bazaar, Richard Avedon photo, Yves Saint Laurent, designer, 1955

Figure 5. Setting up the shot at Cirque d’Hiver with model Dovima, 1955

Figure 6. Avedon’s photo, Saint Laurent’s dress

Two years later, Christian Dior was dead, age 52. And Saint Laurent, age 21 was the head designer of the House of Dior. During the next few years there were some grand successes and a few misses. When Saint Laurent got drafted for the Algerian war, the House of Dior fired him (not quite as quickly, but more brutally). He sued for breach of contract. Dior lost. In more ways than one.

In 1961, Saint Laurent with his business partner, who was at the time also his romantic partner, Pierre Bergé, opened their own fashion house. And there he was, 26 years old, borrowed money behind him and blank sheets of paper in front of him.

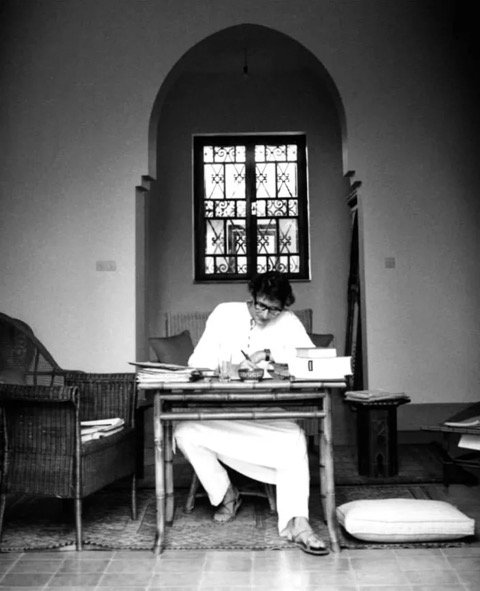

Saint Laurent discovered that he was able to work in Marrakech, (Figure 7) where, according to Jéromine Savignon, (Yves Saint Laurent’s Studio: Mirror and Secrets, 2014) he went twice a year, early June and early December. Each time for two weeks. Here, “(h)e drew, without pause, very fast, without thinking, as if in a state of grace. … He called this the unpredictable ‘miracle of the moment’…On ream after ream of white paper, sketch followed sketch… ‘When I pick up a pencil, I don’t know what I am going to draw. I start with a woman’s face and suddenly the dress follows, the clothing resolves itself. It is creation in its pure state, without preparations, without vision. When the drawing is finished, I am very happy.’”

Figure 7. Yves Saint Laurent at work in Marrakech

And when he returned to Paris at the end of those two weeks, every six months, with his little leather case stuffed with sketches, the army of people who worked with him began to do their magic. Each one having a specialty, each one an integral and essential part to play in the process. They mostly worked in the space that now houses the Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent Foundation. On three floors of exhibition space, the steps from YSL’s initial quick sketches to the final model fittings are traced.

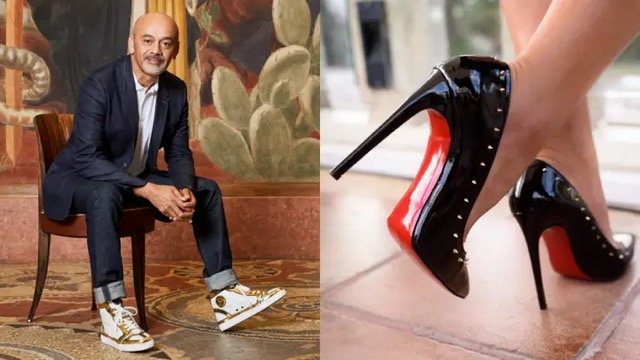

As I read about the strains and constraints of haute couture, I remembered how Thierry Mugler explained why he quit haute couture. Because, he said, haute couture had become all advertising and business. Maybe. His designs were inspired by bugs and spiders (Figure 8) one year and vintage cars and robots another year. He said he adored women and wanted to empower them. But that’s a hard sell if the clothes, made of rubber or silicon or some other synthetic material, are so tight the wearer can’t move. I read somewhere that Diana Ross had to take off the bustier he made for her so she could breathe. (Figure 9) Mugler’s clothes remind me of Christian Louboutin’s shoes. (Figure 10) Which are not made for walking (although his sneakers are).

Figure 8. Thierry Mugler, Bug Outfit

Figure 9. Diana Ross (wearing Thierry Mugler) with Thierry Mugler

Figure 10. Left Christian Louboutin in sneakers, Right Model wearing Louboutin heels

Quick indulgence. I couldn’t help but compare the nude photo of YSL from 1971 with a recent one of the recently deceased Manfred Mugler. The photo of YSL, (Figure 11) when he was 35, was used to advertise his first eau de toilette for men, Pour Homme. He is as thin as a wraith. The photos of Mugler, when he was twice YSL’s age, are of a formerly lithe dancer, who has become “a 240-pound spectacle of muscle and nipple and tatoo”. (Figure 12)

Figure 11. Yves Saint Laurent, photo of designer advertising fragrance for men, 1971

Figure 12. Manfred (Thierry) Mugler, photograph for Interview Magazine, 2019

Both Mugler and Yves Saint Laurent professed to love women. Mugler’s designs exaggerate the female form - wide shoulders, tiny waists, full hips, round bottoms. Perfect hourglass shapes. (Figure 13) His outfits may start with the body of the woman in them, but Mugler ‘Muglerized’ those outfits, those women, to achieve the look he sought.

Figure 13. Some of Thierry Mugler’s designs

Judith Thurman, one of my favorite writers at the New Yorker wrote this about Saint Laurent. “If there is one element, one fil rouge that connects the disparate themes and obsessions of Saint Laurent, it is a love for and empowerment of women..” Chanel may have liberated women from corsets but to be naked under a sheath was another form of tyranny, as Thurman so rightly notes, it is “the oppressive maintenance of a svelte, toned silhouette.…” (Figure 14) Saint Laurent on the other hand, “…anticipate(d) every potential humiliation in the bulge of a seam, the pucker of a pleat, the mockery of a bow. His cutting and drapery are a lover’s discourse with the female body.”

Figure 14. The Chanel suit

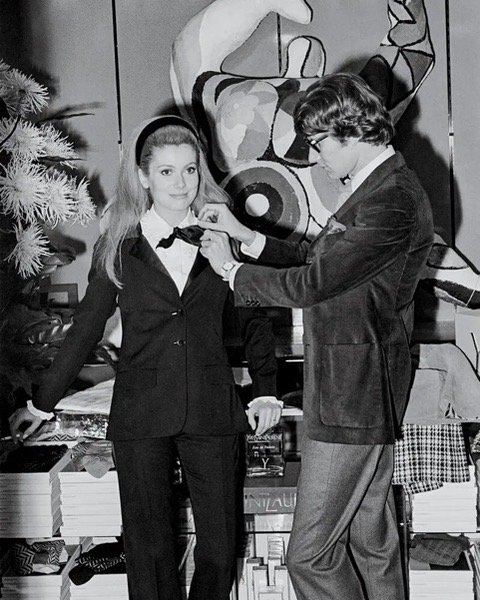

Chanel didn’t design slacks. Yves Saint Laurent did. In 1962. His clothes were ones women could move in, sometimes even relax in, like pantsuits and tuxedos, his most famous ‘borrowing’ from ‘the staples of a gentleman’s wardrobe’. (Figure 15) There’s an anecdote about the wealthy bi-coastal socialite Nan Kempner. When she was denied entry into La Côte Basque restaurant in New York in 1972 because she was wearing an Yves Saint Laurent pantsuit, she simply took off her pants and walked into the restaurant. Reminded me of the protest that women actresses staged at Cannes a few years ago when one woman was denied entry to a screening because she wasn’t wearing heels. Everyone showed up either barefoot or in sneakers. (Figure 16)

Figure 15. Catherine Deneuve getting finishing touches from Yves Saint Laurent

Figure 16. Julia Roberts mounting Red Carpet barefooted at Cannes, 2019

Paintings were often Yves Saint Laurent’s inspiration. That’s museums and art books full of possibilities. Do Yves Saint Laurent haute couture clothes belong in museums? Is fashion art? Is fashion design an art or a craft? Those are not new questions. The separation of arts and crafts has been used to keep what is traditionally considered women’s art, weaving, for example, on a level below the arts that men practice. The noble arts of painting and sculpture.

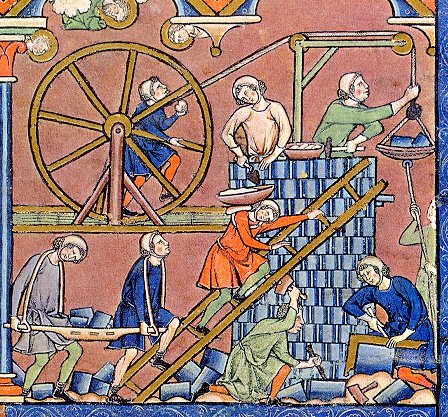

And yet Painting and Sculpture are arrivistes themselves. Until the Renaissance, painters and sculptors were considered craftsmen. They were members of guilds, trade unions. It wasn’t until the 16th century, with Leonardo and Michelangelo, that the status of painting and sculpture really rose. In fact, Leonardo and Michelangelo (and others) debated the relative merits of painting and sculpture in response to a questionnaire they received in 1546, from Benedetto Varchi, Paragone (Comparisons).

Leonardo not surprisingly came out on the side of painting. He contended that the use of color to create illusionistic effects and the intellectual aspects of composing a painting required more mental ability than the physical effort and technical skill required of a sculptor. And a painter can wear fine clothes and listen to beautiful music as he works. A sculptor can do neither. He sweats and gets dirty. And with all the hammering, he can’t listen to music!

Michelangelo, with a foot in both camps, contended that painting is successful the closer it gets to imitating the three dimensional qualities of sculpture which exists in space and can be viewed from many angles while a painting offers only one viewpoint.

The debate helped move these two arts from the Mechanical (Figure 17) those made with the hands) to the Liberal (Figure 18) those created with the mind). Painters and sculptors came to be seen as equals to poets and musicians rather than carpenters and weavers. The social status of artists rose and academies of art were established. Academies that eventually came to be seen as backwards institutions thwarting avant-garde artists like the Impressionists.

Figure 17. The Mechanical Arts

Figure 18. Allegory of the Liberal Arts (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music, dialectic, rhetoric, and grammar)

This exhibition puts gowns and dresses and pantsuits and jackets into museums, juxtaposing with the paintings and sculptures that inspired them. (Figure 19) It was a new concept and yet according to Mouna Mekouar, the co-curator of this multi-museum exhibition, “All six museums were, to our great surprise, unanimously welcoming, The real challenge was to stand out, while still blending into the permanent collections.” To do that, the exhibition curators worked closely with museum directors and curators to make their selections.

Figure 19. Yves Saint Laurent gowns in Dufy Room, Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris

When asked about whether fashion belonged in a museum, Ms Mekouar responded, “I think that, in 2022, we live in a time when we no longer need to ask the question about whether fashion is art, or whether art is art…”

Saint Laurent, according to Ms. Mekouar, “was looking at various civilizations and forms of art and responding to the art of his time,… assimilating an artist’s work to reinvent it… “Even when the reference is direct, there’s always a twist that’s his own.”

Did Saint Laurent believe that the clothes he created were art? According to Alexander Fury (AnOther, September 2018), he certainly did. “(F)rom the middle of the 1980s, the couturier would write the word “Musée” on the labels of various garments, …denoting which garments from the collection should be preserved for posterity, reserved for the then-hypothetical museum in his name.” Among them, the Van Gogh Sunflower jacket worn on the runway by Naomi Campbell. As Fury notes, “It is a masterpiece, (Figure 20) depicting another masterpiece. (Figure 21) History was always important to Saint Laurent. He knew he was making it.”

Figure 20. Naomi Campbell wearing Yves Saint Laurent Sunflower Jacket

Figure 21. Left Sunflowers, Yves Saint Laurent; Right, Sun Flowers, Vincent Van Gogh

You’re familiar when it goes the other way, of course. That is, when artists contribute designs to embellish articles of clothing, well anyhow, purses. Specifically Louis Vuitton purses. In 2001, Marc Jacobs, the creative director at Louis Vuitton hired the street artist Stephen Sprouse to ‘tag’ that is, to create a graffiti version of the LV name and monogram. The bags were a hit. And the ’fashion and art’ formula that Jacobs created is now a fashion industry standard. In the years since 2001, collaborations with artists has become central to LV’s identity, with artists like the dot queen Yayoi Kusama (Figure 22) and the riff king Jeff Koons (Figure 23) and many, many others, invited to try their hand at limited edition LV handbags, purses and totes.

Figure 22. Yayoi Kusama for Louis Vuitton

Figure 23. Jeff Koons for Louis Vuitton

I promised you: Is fashion art. What and how did paintings inspire Yves Saint Laurent. And Proust. Next week, for sure!

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.