Années Folle and Garden Follies

Foujita and the Desert de Retz

Road trip today! We are traveling to two places that are about an hour’s drive from Paris and only 30 minutes from each other One is an artist’s home/studio, the other is a wealthy man’s garden. Let’s start with the artist’s home/studio.

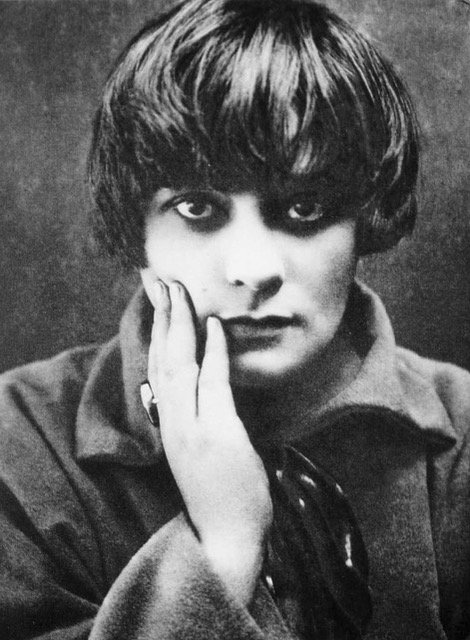

We are off to Villiers-le-Bâcle, (by car or metro/train, up to you) just south of Paris, to the Maison/Atelier Foujita. That’s Tsuguharu Foujita, (Figure 1) who I must admit I knew almost nothing about until I saw the fabulous exhibition of his work at the Musée Maillol a few years ago. That exhibition focused on his work of the Années Folle, (Roaring Twenties). A brilliant decision to concentrate on a decade that seems to have been lots of fun for lots of people. Foujita and his band of artist pranksters among them. Since that exhibition, Foujita seems to be popping up everywhere.

Figure 1. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, photo 1920s

Does that ever happen to you? As soon as you learn about something, it seems to be everywhere. Which gets you thinking, is it always everywhere and you just haven’t noticed or is it only everywhere now? For example, after my son saw the film Troy (he was 10), he became obsessed with the Trojan War. We kept going to the library to find books about the Trojan War and Odysseus’s journey home. Surprising how many versions of Homer’s Odyssey there are for children. One of the decisions Odysseus had to make on his seemingly endless voyage was between Scylla and Charybdis. Between sacrificing a few sailors or risk losing all of them. And for a while, no matter what book I read or newspaper I perused or radio commentary I listened to, there always seemed to be a reference to Scylla and Charybdis And then it stopped. So, how to account for that synchronicity? I just don’t know.

Anyhow, here’s an example of what I mean about Foujita. The exhibition I saw last year at MAJH (Museum of Jewish Art & History), called ‘Paris pour école, 1905-1940’, was mostly about the Jewish artists who fled their homelands to become painters in Paris. But almost in every photo I saw, there was Foujita. Would I have noticed him if it hadn’t been for that exhibition at the Maillol? I don’t know. But he came to Paris for the same reason that all those other artists did. Turns out that Foujita didn’t stay in Paris until 1940, which was a good thing. But he did find himself in Japan in the 1940s, painting propaganda pictures for the Japanese government, which was not a good thing. At least in retrospect. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

Tsuguharu Foujita was born in Japan in 1886 into a samurai family. His father was a general, a doctor, in the Japanese Imperial Army. By the year of Foujita’s birth, Japan had been open to the West for only about 30 years. There was a fascination with the western world in Japan and a fascination with things Japanese in the West. Foujita’s fascination was with France. He began learning French in elementary school. That he was a gifted artist was apparent from the beginning. And when he graduated from the Imperial School of Fine Arts, having studied western painting, he knew exactly where he was going.

Foujita explained it this way, “It was predicted that I would be the best painter in Japan, but I dreamt of being the best painter in Paris.…” So, diploma in hand, he made his way to Paris in 1913. And found himself at the Cité Falguière, a low cost live/work space for artists. (Figure 2) developed by the sculptor J-E dBouillot, who had achieved success and wanted to make low rent studios available to artists who hadn’t been (or weren’t yet) as successful as he. And he named his development after his teacher, Alexandre Falguière, Interestingly, at the same moment, La Ruche, (Figure 3) the three-story circular structure that got its name because it looked more like a large beehive than a dwelling for humans, opened with the same mission. Low cost studios for struggling artists. Artists like Soutine and Modigliani wandered between the two. Easy enough since they are only 20 minutes apart on foot.

Figure 2. Cité Falguière, Paris, recent

Figure 3. La Ruche, Paris, 1918

Foujita met Soutine and Modigliani at Cité Falguière. A few months later, he met Picasso. And began taking dance lessons from Isadora Duncan. His circle of friends widened, of course, and came to include the other young artists of the day, from Fernand Léger to Henri Matisse. As it turns out, being Japanese gave Foujita an extra cachet. He was able to combine Japanese painting techniques with French ones to achieve something that was new and fresh when all of his friends and colleagues were struggling to find their own new and fresh.

Sometimes his work looks like Japanese art influenced by Western techniques and sometimes Western art influenced by Japanese techniques. (Figure 4) But it never looks like any body else’s work. Foujita’s touch was delicate, his hand was sure and his lines were pure, almost like calligraphy. At a time when Matisse’s canvasses were bursting with color (Figure 5) and when most of the artists around him were using large brushes, often thick with paint, (Figure 6) Foujita used a thin brush and black and white paints. He used a white glaze, that all the artists who saw it were mad to learn how to make. (Figure 7) But Foujita kept his recipe secret for years. Although I imagine that any Japanese artist would have known the formula - flaxseed oil mixed with crushed chalk and magnesium silicate.

4. Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita, “Portrait of Emily Crane Chadbourne” 1922, oil, silver foil, gold powder on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago/Art

Figure 5. Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1904

Figure 6. Chaim Soutine, Houses, 1920

Figure 7. Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Nu couché, (Youki) 1923

As he played with styles, Foujita played with the art of self presentation. (Figure 8) Lithe as a dancer, his hair in a bowl cut, often topped by a bowler hat, rings in his ears, his glasses round a la Corbusier (Figure 9) and his mustache a smudge between his nose and lips (I’m not going to tell you what that smudge reminds me of). His outfits were often of his own construction, sewed together from unlikely components that were somehow just right for him. During the Roaring Twenties, when everybody was trying to stand out in the crowd, Foujita always did. He was exotic, he was original. He hammed it up for every camera, still or moving, that found him. (Figure 10)

Figure 8. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita 1926

Figure 9. Le Corbusier

Figure 10. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita with friends at a Cabaret

He found his own visage as interesting as others did, based upon the number of self portraits that survive. One of which, from 1927, at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris shows him with his beloved cat, Miké. (Figure 11) Foujita holds a brush and wears his round glasses. There is no mistaking him for anyone else. Miké gazes contentedly at Foujita.

Figure 11. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Self Portrait with Miké, 1927

Figure 11 a. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Self Portrait with Miké, photograph

He loved painting cats and naked women. Sometimes on the same canvas. (Figure 12) He said this: “I believe that felines were given to men so that they could learn from them about women.” He also suggested that women would be well advised to study the behavior of cats.

Figure 12. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Youki with Cat, 1923

Foujita achieved financial success far more quickly than his fellow Montparnasse artists. In the exhibition at the Maillol, there are videos which show him cavorting on the beaches of Deauville and the Côte D’Azur. There are hints that he was playing the clown because that was what was expected of him as an ‘exotic’. Who knows, maybe he enjoyed it, maybe he was having fun. But at least it had its rewards. For example, in 1928, he was invited to stay at the Normandy Hotel in Deauville.To stay as long as he wished and to eat as many lunches and dinners at the hotel as he desired. The reason, according to Foujita was that when he was there, other people wanted to be there, too. He was what we call now, an influencer. It was and still is a relatively cheap way for hotels and restaurants to advertise. (Figure 13)

Figure 13. Photo of Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita at Deauville

Foujita was also quite a ladies man. He was probably already married when he arrived in Paris in 1913. At his request, his father annulled that union in 1916. It was clear to him that he wouldn’t be returning to Japan to be a married man in a tradition bound country. In March 1917, he met Fernande Barrey at the Café de la Rotonde. (Figure 14) He pursued her and she eventually acquiesced. By which I mean that when she first saw him at La Rotonde she ignored him. But when he appeared at her doorstep the next morning with a blouse he had made for her during the night, she opened the door and let him in. They were married thirteen days later.

Figure 14. Photograph of Fernande Barrey, 1920

Foujita’s first studio became the envy of all when he had a bathtub installed. A bathtub with hot running water. Among the models who came for a bath and stayed for a portrait was Kiki de Montparnasse, at the time May Ray’s lover. When she arrived, she was naked under her coat. Perfectly dressed for the portraits Foujita painted of her. She posed on a sofa which he surrounded with Toile de Jouy fabric. This painting is titled, appropriately enough "Reclining Nude with Toile de Jouy" (Figure 15) It’s at the Musée d’art moderne.

Figure 15. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Reclining Nude with Toile de Jouy, 1922

You can see that Foujita had spent time at the Louvre and and the galleries. There are hints of Titian and Manet. (Figure 16) Languidly posed, full frontal nudes, unheard of in Japan. But this painting is completely Foujita’s own. Kiki’s skin is so white. The hair - on her head, under her arms, on her pubis - is so black. He is channeling his Japanese predecessors, too. The pearly-white bodies of Geishas in Japanese prints of the 18th and 19th centuries. (Figure 17) I think about all the Japanese women I have seen in San Francisco and Paris, wearing gloves in the summer, holding umbrellas to protect themselves from the sun. Trying to stay as fair as possible. Foujita’s painting was a highlight of the 1922 Salon d’Automne.

Figure 16. Edouard Manet, Olympia

Figure 17. Utamaro, Ykiyo-e, or Images of the Floating World, Edo period

A year before that painting, he became involved with Lucie Badoul, whom he called Youki, or "Rose Snow” because of how white her skin was. He was still married to Fernande. They had an open relationship. But Fernande crossed the line in 1925 when she had an affair with his cousin, also a painter. I guess he didn’t mind her sleeping with European men or women, but another Japanese man and his cousin to boot, well that was going too far. They divorced and Lucie Badoul became Foujita's third wife. By 1927, he had made so much money that he bought Youki a fancy car with the requisite chauffeur.

When Foujita left France in 1931, ostensibly to travel, it was really to evade a huge tax bill because somehow he hadn’t been putting any money aside to pay his taxes on the fabulous amounts of money he had been making. He left Youki behind, entrusting her to the care of her lover, his rival, the surrealist poet, Robert Desnos.

Foujita took a new love, Mady, with him. They traveled first to South America where he was much in demand and then to Japan. And although he was in Paris briefly in 1939, from 1933 to 1950, he was mostly in Japan. And the eccentric, antic loving bohemian became a war artist, painting propaganda pieces for the war against the United States and Allies. (Figure 18)

Figure 18 Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, War Propaganda Painting, 1943

Foujita did return to Paris in 1950, with the help of some wealthy American art collectors. But it wasn’t the Paris he had left in 1931. As one writer put it, by the time Foujita came back to Paris, the exciting, experimental center of art had moved to New York. And Foujita was not the same either. His participation in the war had not been forgotten. He was called a fascist and imperialist by fellow Japanese.

When he returned to Paris for this final time, Foujita was accompanied by Kimiyo, his fifth wife and like his first wife, Japanese. In quick order, he renounced his Japanese citizenship, became a French citizen, converted to Catholicism, changed his name to Leonard (in honor of Leonardo de Vinci) and found the little 18th century house that I visited, which he lived in until his death (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Foujita’s Last House

While there are some remnants of and references to the grand life that had been Foujita’s during the flashy Années Folle, it is the final years and the simple life he led here that we mostly see. (Figure 20) He had purchased a ruin and transformed it into a livable space with his own interior decorations and furniture. Although it was no longer the Roaring Twenties, there were about 10 small casts that the guide (you can only visit the house with a guide) showed us and asked if we could figure out what they were.(Figure 21) At first I guessed nipples. But I knew that couldn’t be right. My second guess was, they were casts of belly buttons. Foujita’s playfulness and whimsey had survived !

Figure 20. Foujita Last House, bedroom

Figure 20a Foujita’s Little decorations throughout Last House

Figure 20a. Foujita tin foil objets at Last House

Figure 21. Foujita, Belly Button molds of friends at Last House

In his upstairs studio, we see what he was working on during the last years of his life. It was after a mystical experience in Reims, that he converted to Catholicism. And it was there, in 1966, that he built and decorated a Romanesque style chapel Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix Chapel, in the garden of the family residence of the Mumm champagne house. (Figure 22) Foujita decorated the chapel with frescos of scenes from the life of Christ. (Figure 23)

Figure 22. Foujita Chapel, Reims, France

Figure 23. Foujita Chapel interior, Reims, France

What to say about these paintings, sketches and drawings of which are on the walls and easels of his studio. (Figure 24) There is a hyper realism about them. One critic wrote that they looked like cartoons. They remind me of the bible illustrations that James Tissot drew at the end of his life. (Figures 25, 26) Foujita died in 1968 and is buried in the chapel at Reims.

Figure 24. Foujita Studio, Last House

Figure 25. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Crucifixion, Chapel, Reims, France

Figure 26. James Tissot, Resurrection

Thirty minutes from Villiers-le-Bâcle is the Dersert de Retz. (Figure 27) It was on my list of places to visit for a few reasons. True American that I am, I knew that Thomas Jefferson had remembered it when he designed Monticello and the library at the University of Virginia. Cultural preservationist that I am, I knew that André Malraux, in a 1966 speech to the National Assembly, called upon that august body to evoke the Loi Malraux, passed four years earlier, to save this very special garden, as an historic monument: “(W)here, … the most important remains of 18th century Chinese monuments in Europe are to be found,” But whose owner, “a forestry merchant was letting them fall not into ruins, but into dust” Which seems fitting, doesn’t it, from a forestry merchant.

Figure 27. Desert de Retz

By the time Malraux called upon the Assembly to save the Desert de Retz, the Loi Malraux had already saved the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the Perigord, Sarlat (near my summer home) and the Marais in Paris (near my year round home).

And finally, as a person obsessed with signs and symbols, I wanted to know if the structures that dotted the landscape in this garden add up to any coherent symbolic program.

The Désert de Retz is a garden on the edge of the Marly Forest. It was created by Francois Racine de Monville. (Figure 28) An aristocrat born in 1734, the son of a Treasurer-General who was found guilty of fraud in 1742 and who died in prison eight years later. His son, the hero of this story, was raised by his maternal grandfather, a tax-farmer who collected taxes for the government. Luckily he wasn’t found guilty of keeping too much of the money he collected, as his son-in-law had been.

Figure 28. Portrait of Francois Racine de Monville

In 1775 de Monville married his third cousin Aimable Charlotte Lucas de Boncourt. After five years of marriage, his wife amiably died. His grandfather died a few months later leaving him a large income. Conveniently widowed with no children, his sybaritic lifestyle didn’t bother anyone, except perhaps a jealous husband or two, or probably more.

He bought up properties between 1774 and 1786 in the neighborhood of the village of Retz, to create a garden retreat. He did not envision a French garden with its symmetry and straight lines but an Anglo-Chinese garden with curving lines and surprising vistas. Scattered around were 20 follies or “fabriques”.

The word desert in Désert de Retz, following the 17th century definition, is an isolated place, conducive to dreams and nostalgia. That was the meaning that Monville was after for this property on which he planted four thousand trees purchased from the royal greenhouses, And on which he rerouted a river and created ponds.

The garden was completed in 1785. Among the architectural follies were a ruined Gothic church (figure 29) which may have been the only actual ruin on the property, a ruined altar, a classical tomb, an obelisque, a temple to the god Pan, (Figure 30) a Tatar tent, (Figure 31) and an ice-house in the form of a pyramid. (Figure 32)

Figure 29. Gothic Ruin, Desert de Retz

Figure 30. Temple to the God Pan, Desert de Retz

Figure 31. Tartar Tent, Desert de Retz

Figure 32. Pyramid Ice House, Desert de Retz

The best-known follie, is the ruined classical column, a "colonne brisée". The base of a column from a gigantic temple that never existed.(Figure 33) It is six stories tall, with small oval rooms arranged around the circular staircase. (Figure 34) Nobody knows why Monville built it, but three decades after he saw it in 1786, Thomas Jefferson adapted its floor plan to his layout for the Rotunda at the University of Virginia.(Figure 35)

Figure 33. Broken Column, Desert de Retz

Figure 34. Broken Column, Interior, Desert de Retz

Figure 35. Rotunda of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia

Figure 35a. Inside the Rotunda, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia

There are theories that the garden alludes to Free Masonry. And there are Masonic symbols, if I am remembering my American $1 bills correctly - broken columns, pyramids, etc. But according to experts, if it was meant to relate to Masonry, there would have been a symbolic path for the initiated and a structure to use as a Lodge. Alas, there is neither and no contemporary sources mention any connection.

Monville welcomed famous visitors to his garden, from Marie-Antoinette and the painter Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun to Madame du Barry and Gustave III of Sweden, and of course, Thomas Jefferson, who brought Maria Cosway with him. The painter Hubert Robert visited and maybe Benjamin Franklin visited, too.

Unfortunately, as it turned out, Monville did not have much time to enjoy the Desert de Retz. It was confiscated by the revolutionary government which did however, spare Monville’s head. He died in 1797, a much poorer man than when he started out.

In the 20th century, artists like Salvador Dali and Andre Breton visited, the later brought 23 other surrealists with him. French President Mitterrand came in 1990 and the architect I. M. Pei was there in 1994. At least three films have scenes shot at the Desert de Rez, including the 1995 film by James Ivory called Jefferson in Paris starring a very miscast (IMHO) Nick Nolte, who, like Jefferson had done, brought a Maria Cosway with him.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.