If you build it, they will take it - Part 1.

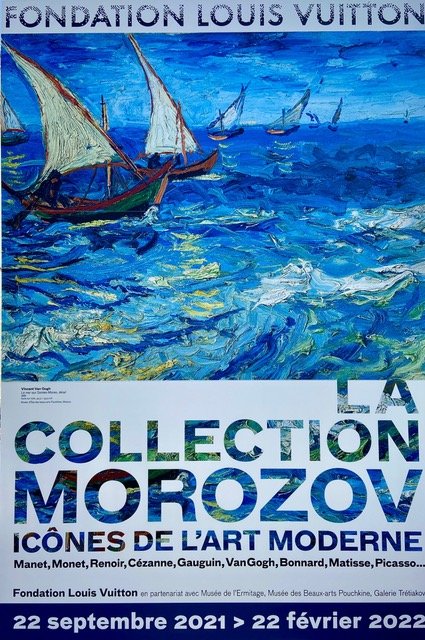

The Morozov Collection. Icons of Modern Art. Fondation Louis Vuitton.

If you have ever read or browsed through an introduction to the history of art, say by Janson or Gardner, you know that each period of art is illustrated by a few works, often paintings, that come to define that period in art. And you don’t really pay much attention to where the paintings themselves are, just assuming, if you think about it at all, that they are probably in one of the world’s grand museums - the Louvre, the Met, the National Gallery. And again, you don’t much think about how they got into those museums. That is to say, their provenance, who they were painted for and where they have been between then and now, on those museum walls. Once in a while I will go to a museum for a temporary exhibition and see a painting that I know as well as I know the faces of my own children. (Figure 1) And then I will read the label and sometimes note with surprise that the painting is from a museum I have never visited, a collection I have never seen.

Figure 1. Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, (1866 version) Edouard Manet, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Figure 2. Exhibition Poster for Icons of Modern Art, the Shchukin Collection, Fondation Louis Vuitton, 2016-17, detail of Van Gogh ‘Portrait of Dr. Felix Rey’ 1889

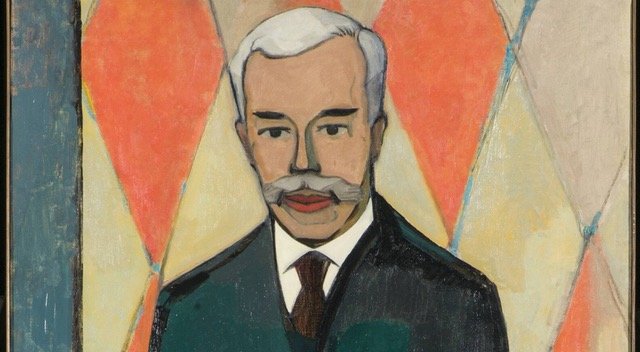

And that’s what happened in 2016 when the Fondation Louis Vuitton held an exhibition of French Impressionist art. (Figure 2) There is, of course, a lot of French Impressionist art in Paris, especially at the Musée d’Orsay. So as an idea, an exhibition of Impressionist art in Paris, isn’t too exciting. Except of course, this wasn’t just any collection of Impressionist art. This was an exhibition of paintings on loan from two national collections in Russia - the Pushkin and the Hermitage. That exhibition was a blockbuster. Now, five years later, history has repeated itself. Except for the year long delay caused by Covid. That was new. The French impressionist paintings on display this time are also from the Pushkin and Hermitage Museums. And like last time, this collection was amassed by a wealthy collector, actually two collectors, two brothers. The first exhibition, called Icons of Modern Art featured the collection of Sergei Shchukin. (Figure 3) The current exhibition, also called Icons of Modern Art, (on view until 02/ 22/22), is the collection of Ivan Morozov. (Figures 4 & 5) Both collections were seized during the Russian Revolution.

Figure 3. Portrait of Sergey Shchukin, Christian Krohn, 1916

Figure 4. Portrait of Ivan Morozov, Valentin Serov, 1910

Figure 5. Fruit and Bronze, Henri Matisse, 1910, Pushkin Museum, Moscow (painting behind Morozov)

Honestly, if it weren’t for totalitarian regimes seizing private art collections, whether in Russia during the Revolution or in Germany and everywhere else those awful Nazis got to, during the Second World War, I don’t know what any of us would be looking at on museum walls. Well, that’s not entirely true. In the United States we also have our robber barons, like Getty and Frick and Carnegie, to thank. They were able to amass great fortunes by not paying their employees a living wage. And then using the money they weren’t spending on lavish trips and opulent homes, to buy up all the art they could find, often from impoverished European nobility forced to liquidate their family’s patrimony. Of course they bequeathed their collections to museums that bear their names or in some way celebrate their largesse. I refuse to talk about the Sackler family who cleverly amassed a fortune by selling opioids and then succeeded for a long time in presenting themselves as enlightened patrons of culture and the arts by paying for Sackler Wings everywhere from the National Gallery in London to Harvard University in Cambridge (the ‘Sackler’ name has now been mostly removed).

So, getting back to these works of mostly French, mostly Impressionist paintings from Russian museums. Paintings and sculptures that were taken, stolen, looted from their owners, the industrialists who paid for them and collected them.

You might remember that the book I reviewed last week, The Vanished Collection (you can read that review here: Perils of Pauline) was about the author’s effort to have her great grandfather’s Nazi looted paintings returned to his heirs. From museums which had gained possession of the paintings sometime after they had been stolen by the Nazis, mostly without knowing (or asking about) the paintings’ provenance. This is a very different situation. These are two collections whose collectors are known and whose collections remain in public museums in the country that stole them.

We all know that the 1917 Russian Revolution overthrew the tzar. And that the Bolsheviks came into power. Among their various ‘innovations’ was the nationalization of property: land, homes, works of art. Ivan Morozov’s art collection and mansion were declared ‘state property' In 1918. The collection was seized. Morozov was not compensated.

Hmm, I wondered (as you must be, too) have the descendants of Sergei Shchukin and Mikhail & Ivan Morozov tried to get their art collections back? Turns out they have.I guess you won’t be too surprising to learn that the heirs have made no headway with the Russian government. But each time paintings from one of these grand collections are loaned to a country with a functioning judiciary, the families have tried again.

Here are just a few examples. In 1954, the Soviet government sent a group of Picasso canvases to Paris for an exhibition of his work at La Maison de la Pensée Française. (Figure 6) Sergei Shchukin’s daughter, who lived in France, learned of the exhibition and demanded the return of 37 paintings. They were immediately shipped back to Moscow.

Figure 6. Maison de la Pensée Français, Poster, Picasso 1954

In the early 1990s, Shchukin’s daughter tried again. She sent a letter to President Yeltsin demanding that he admit the illegality of the nationalization of her father’s collection. Not surprisingly, he didn’t respond. So, in 1993, when the Pompidou borrowed some of Shchukin’s paintings for a Matisse exhibition, she asked a French court to impound the catalogues. She claimed that her family’s paintings had been reproduced without her permission. She lost the case.

Since her death, her son André-Marc Delocque-Fourcaud has continued her struggle. In 2000 he asked a Roman court to seize a painting by Matisse which was featured in the exhibition “100 Masterpieces from the Hermitage”. (Figure 7) To avoid any hassle, the painting was sent back to Russia.

Figure 7. Danse, Henri Matisse, 1910, Sergei Shchukin collection.

In 2003 it was the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s turn. An exhibition of works from the Pushkin Museum was held. Delocque-Fourcaud demanded a share of the profits. Some exhibitions make lots of money. He argued that he had a right to a cut. His suit was dismissed by the U.S. district court.

From France to Italy to the United States. In 2008, it was England’s turn. The British Royal Academy organized an exhibition of French impressionist art. The Russians demanded that the British guarantee the works’ immunity. The RA offered the Shchukin and Morozov heirs £5,000 ($9,825) each in exchange for their promise not to make claims on the paintings when they were in London.

Delocque-Fourcaud called the RA’s offer insulting (who wouldn’t) and unnecessary. “The exhibition was in preparation for at least two years, but the Royal Academy remembered us at the last minute. If I had been addressed when the show was in preparation and asked politely and properly not to create legal problems for the exhibition because of its cultural importance, if I had been invited to the opening, I would have guaranteed my support without a moment’s hesitation. Instead, I was offered a bribe at the last minute…”

The way Delocque-Fourcaud sees it is that the Shchukin and Morozov collections were nationalized during a ‘utopian time’. But today “Russia is a capitalist country where quite a few citizens enjoy private property. So, the government should … acknowledge past injustices and offer compensation. …”

Neither heir (both of whom live in France) expects the restitution of their ancestors’ art collections. What they are asking for is a percentage of what a museum makes from all the stuff it sells in conjunction with an exhibition of their patrimony. Because, as we all know, exhibitions are not just cultural events, they generate a lot of money. The heirs want a cut.

Another tactic Pierre Konowaloff, Ivan Morozov’s great grandson and heir tried was suing two American institutions which each have a painting that belonged to his great grandfather. Both paintings are icons of modern art. Yale University Art Gallery owns van Gogh’s The Night Café. (Figure 8) The Met is home to Cézanne’s portrait of his wife, “Madame Cézanne in the Conservatory.” (Figure 9) In 1933, the Soviet government needed cash, so the government sold these (and other paintings) to a gallery in Berlin. Which sold them to a gallery in New York (Knoedler). Which sold them to Stephen Clark, heir to the Singer Sewing Machine Company fortune. Clark bequeathed one painting to Yale and the other to the Met.

Figure 8. The Night Cafe, Vincent van Gogh, Yale University Art Gallery

Figure 9. Mme Cézanne in the Conservatory, Paul Cezanne, Metropolitan Museum of Art

So, here is a question: Is there a difference between those two paintings and Egyptian antiquities that the Met acquired as innocently as it acquired the painting from Clark? And that the Met returned to Egypt? And what about the demand by the heirs of Holocaust victims for the return of art stolen by the Nazis? Shouldn’t claimants to art taken by the Bolsheviks be treated the same way?

Somehow it wasn’t until 2008, that Pierre Konowaloff, (Morozov’s heir) learned of the whereabouts of the two paintings Clark had purchased. He filed a complaint against Yale in 2009 for the return of the painting by van Gogh. The next year, he filed a complaint against the Metropolitan Museum for the painting by Cézanne

For Konowaloff’s lawyer, the return of art looted by Nazi is precedent for claims for the return of art looted by the Bolsheviks, because “by the 20th century we had in place international laws and conventions that prohibited the seizure of cultural property without compensation.”

As one commentator put it: “We cheer for the families who have spent generations trying to recover their priceless treasures systematically stolen by the Nazi regime before and during World War II. The full energies of our courts and legal system have been single-minded in their devotion to repatriating stolen Holocaust works to true owners. And when successful, we applaud these efforts and feel good about justice served.” But as the same commentator also noted, in 2015, the United States Court of Appeals rejected that argument advanced by Morozov’s heir.

Konowaloff lost both cases because of the United States’s Act of State Doctrine which contends “that the validity of a foreign state’s act may not be examined even if it violates customary international law or the foreign state’s own laws.”

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case after it had been turned down by lesser courts. There are no more legal options available to Konowaloff. Restitution of these two paintings is not going to happen. The fight which Morozov’s heir began in 2008, a century after his great grandfather bought the painting still at Yale has concluded a century after it was stolen by the Bolsheviks.

Both the Shchukin and Morozov exhibitions at the Fondation Louis Vuitton post date the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision. But preparation for both exhibitions began years before it. Work was done in the archives to sort out ownership. After years of being locked up in storage, conservation was a pressing issue. For the Morozov collection, a ‘pop-up’ conservation laboratory was set up in Russia. And like all the other international exhibitions before it, and like the Shchukin exhibition five years ago, “this one required a colossal diplomatic effort, with assurances that French law would protect the Russian museums against any claims by the Morozovs’ descendants”.

I’ve got to tell you, all of this has made me a little uneasy. Am I, is everybody who attends this exhibition and the one before it, complicit in validating a gross miscarriage of justice. Or should we imagine that Bernard Arnaud, an enormously wealthy industrialist and collector of contemporary art, has considered his Russian predecessors’ heirs demands to be reasonable and has agreed to give Shchukin’s and Morozov’s heirs a percentage of what people spent in tickets and stuff? I hope so. Next week I’ll discuss the fabulous works of art themselves.

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.

Bibliography

Fighting for Their Rights, Konstatin Akinsha, Grigorij Kozlov April 1, 2008

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/fighting-for-their-rights-196/.

Heir Files Claim for Met’s ex-Morozov Cézanne: Is Bolshevik Loot Like Nazi Loot? Lee Rosenbaum December 13, 2010

https://www.artsjournal.com/culturegrrl/2010/12/claim_filed_for_mets_ex-morozo.html

Holocaust Art Recovery Cases: Cezanne and Van Gogh November 16, 2015 Holocaust art recovery cases are the most compelling cases in fine art law

https://www.wasserruss.com/holocaust-art-recovery-cases/

Man Loses Quest to Reclaim $200 Million Van Gogh Painting Seized by Bolsheviks After years in court, the painting will remain at Yale. Sarah Cascone, March 29, 2016

https://news.artnet.com/market/vincent-van-gogh-yale-night-cafe-lawsuit-461216