If you build it, they will take it - Part 2

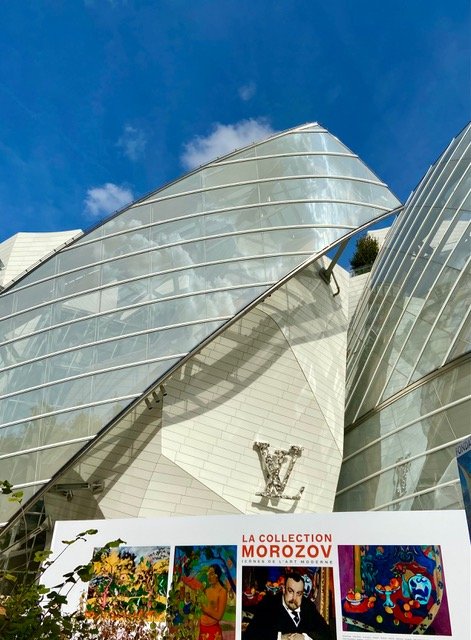

The Morozov Collection. Icons of Modern Art. Fondation Louis Vuitton.

So, getting back to those Russian collectors. As we know, wealthy 19th century Parisian bankers like Moise Camondo and Edouard André and successful entrepreneurs like the founders of La Samarataine, all collected art. But if they collected French art, they mostly collected paintings and sculptures that were at least 100 years old. Art that was risk free because it was already pedigreed. These Russian collectors did something different. They went for contemporary French art. What made them so adventurous? And why French art?

A (very) little history. The Russian aristocracy’s love affair with all things French flourished in the eighteenth century. It reached its peak during the reign of Catherine the Great. She was a great admirer of both Voltaire and Diderot. She subscribed to Diderot’s Encyclopedie and purchased both philosophers’ libraries. That happened during Diderot’s lifetime and came with an annual stipend, which kept him solvent. Diderot even made the trip to St. Petersburg to see his benefactress in 1773. (Figure 1) They had no trouble communicating because they both spoke French. The language of the Russian nobility at court and at home, too. So they could speak to one another and in front of their servants assured that even if what they said was overheard, it wouldn’t be understood.

Figure 1. Diderot meeting his benefactress Catherine II of Russia, 1773

Why French? By the 18th century, French had replaced Latin as the international language of commerce. And aristocratic Russians not only learned the language, they learned the culture. The Napoleonic wars not withstanding, they filled their homes with French tutors and French decorative arts. The nobility had their portraits painted by artists, mostly French. And Russian artists traveled to Paris well before the turn of the 20th century, before the generation documented in the Paris for School exhibition at the MJAH last year.

So, perhaps a little less surprising to learn that wealthy Russian art collectors purchased French art in the late 19th century. But it continues to be quite astonishing to see what the textile merchant Sergei Shchukin (1854–1936) (Figure 2) and the textile manufacturers, the brothers Morozov, Mikhail (1870-1903) (Figure 3) and Ivan (1871–1921) (Figure 4) purchased. When they could have bought anything they wanted.

Figure 2. Sergey Shchukin, Christian Krohn, 1916

Figure 3. Mikhail Morozov, Valentin Serov, 1902

Figure 4. Ivan Morozov, Constantin Korovine (1903).

Rosamund Bartlett (Apollo Feb. 2021) addressed an issue I had been wondering about. Nobles vs New Money. Money that had been inherited vs Money that was still being earned. As she notes, at the beginning of the 19th century, the nobles were cultured, the nouveau riche were crass. But by the 1890s, not only were the ‘merchant millionaires’ swimming in money, they knew how to spend it. “Suddenly there were dozens of young men born into great wealth who were also educated and deeply cultured,” having “attended the same elite schools and universities as the sons of aristocrats.” Among that group were Sergey Shchukin and the brothers Morozov.

Sergei Shchukin was one of ten children born into a family of textile merchants. During its heyday, Sergei Shchukin’s company was one of the largest manufacturing and wholesale businesses in Russia. He began collecting Impressionist paintings when they were still being rejected by the French. When paintings by Monet were condemned by French critics as mere ‘Impressions’. By 1904, Shchukin owned 14 Monets. (Figure 5) Two years later, he met Henri Matisse and became one of Matisse’s major patrons, acquiring 37 paintings in 8 years. Matisse introduced Shchukin to Picasso and by 1914, Shchukin owned the largest collection of Picassos in the world, 51 pictures in all.(Figure 6) During his frequent trips to Paris to visit art galleries and artists, he discovered Paul Gauguin, then Cézanne and Van Gogh. But buying art wasn’t, in and of itself, enough for Shchukin. He wanted to share his collection with the public. So for over a decade, Shchukin opened his home on Sundays and personally gave tours of his collection to visitors.

Figure 5. Déjeuner sur l’herbe, Claude Monet 1866

Figure 6. The Absinthe Drinker, PIcasso, 1901

The Shchukin exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in 2016-17 was a ‘Once in a Lifetime’ event. And as I mentioned last week, I saw paintings that I recognized, paintings that were like old friends. Old friends I had seen only in books until then. Turns out the Shchukin Exhibition was only ‘Once in a Lifetime' Part 1. ‘Once in a Lifetime’ Part 2, the Morozov Collection is at the Fondation Louis Vuitton now, until February 22.

Mikhail and Ivan Morozov were the great-grandsons of a serf who started building his empire with five rubles from his wife’s dowry. A century before these brothers were born, the patriarch opened a silk ribbon workshop, which became a factory, which he used to buy his family’s freedom. By the 1870s, theirs was a family of wealthy industrialists. Their philanthropy, proof that they hadn’t forgotten their roots.

The Morozov brothers’ interest in art started early. Their widowed mother, a philanthropist, augmented their excellent education, which included French lessons, of course, with weekly art instruction given by a young artist who would come to be called the ‘Russian impressionist’ Konstantin Korovin. (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Flowers and Fruit, Konstantin Korovin, 1911

The brothers initially focused on collecting works by young Russian painters. But soon they began to purchase French art, too. Here are some of the Morozov brothers firsts. In 1898, Mikhail started taking regular trips to Paris. In 1900, he discovered Pierre Bonnard and became the first Russian collector to buy a painting by Gauguin (from the gallerist Ambroise Vollard). In 1901, he was the first Russian collector to buy a Van Gogh. A few years later he purchased a Renoir portrait from the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery. In 1903, at the Salon des Indépendants, just a few months before his death at age 33, he branched out and became the first Russian collector to buy a work by Munch. By the time of his death, his collection included 39 works by French artists, including Monet, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec.

Ivan picked up where his brother left off. In 1904, he began making bi-annual trips to Paris for the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne. While he was in Paris, like his brother before him, he visited art dealers and artists in their studios. On his art first trip, he bought paintings by Renoir, Vuillard, Pissarro, and Sisley.

In 1907, he bought his first painting by Cezanne. (Figure 8) Anne Bristoldi, the curator of this and the Shchukin exhibition, who began researching the Morozovs in Russian archives in 2014, tells us that Ivan “became a convinced Cézannist, acquiring 18 outstanding canvases that he hung in a ‘secret’ study next to his private apartments.”

Figure 8. Le Fumeur, Paul Cezanne, 1890

In 1908, Morozov bought Van Gogh’s Le Café de Nuit, (Figure 9) painted in 1888 (now at Yale which I wrote about last week), at one of the first exhibitions of French and Russian avant-garde art to be held in Moscow. Another painting by Van Gogh, The Prison Courtyard (Figure 10) has been given a room of its own at this exhibition. Painted in 1890, when he was at the psychiatric hospital in St. Rémy it recalls a photograph his brother Theo sent to him of a drawing by Gustave Doré. (Figure 11) A prison courtyard in London. It must have fitted perfectly with how Van Gogh was feeling about his own confinement.

Figure 9. Le Café de Nuit, Van Gogh

Figure 10. Prison Courtyard, Van Gogh, 1890

Figure 11. Newgate Prison Courtyard, Gustave Doré, drawing, 1872

Morozov invited both Maurice Denis and Pierre Bonnard to Moscow to create paintings for his mansion.

In 1908, Denis painted the ‘Story of Psyche and Cupid’ on large panels for Morozov’s music room. (Figure 12) The room has been faithfully re-created at the Fondation. Embellished as the room originally was, by four statues by Aristide Maillol. (Figure 13).

Figure 12. Music Room of Ivan Morozov, Maurice Denis 1910 reconstituted at Fondation Louis Vuitton

Photo of Morozov Music Room

Figure 13. Statues, Aristide Maillol, in Morozov Music Room

Maillol Statue, detail

In 1910, Morozov commissioned Bonnard to paint a triptych, La Méditerranée, to decorate the main staircase of his mansion. (Figure 14)

Figure 14. Triptych La Méditerranée, 1910

In 1912, he asked Matisse to create a triptych, which, not surprisingly after the artist’s long stay in Morocco, became the Triptyque Marocaine.(Figure 15)

Figure 15. Central Panel, Triptych Marocaine, Matisse, 1912

Matisse sketch of Triptych Marocaine

Shchukin may have eventually owned the largest collection of Picassos, 51 paintings by the time he stopped collecting. But it was Morozov who first brought a painting by Picasso to Russia when he bought Les Deux Saltimbanques in 1908. (Figure 16) He only bought two more Picassos but they are fine examples of the artist’s work, Acrobate à la Boule from Picasso’s Rose Period. which had been owned by Leo and Gertrude Stein and the Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (Figure 17), the sole example of Cubism in Morozov’s collection.

Figure 16. Les Deux Saltimbanques, Picasso, 1908

Figure 17. Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, Picasso, 1910

Shchukin stopped collecting in 1914, perhaps he saw the direction the country was going. Morozov continued for three more years, collecting modern French and Russian art simultaneously. As with his taste in French art, Morozov went only so far with avant-garde Russian art. He bought works by Larionov (Figure 18) and Goncharova,(Figure 19) (two of my favorites) but not by Kandinsky and Malevich.

Figure 18. A Resting Soldier, Mikhail Larionov, 1911

Figure 19. The Cyclist, Natalia Goncharova, 1913

Here is the final tally - between 1904 and 1914, Ivan bought 240 works by French artists. And his Russian art collection, which began in1891, included 430 works by the time he was done. One of his last purchases were paintings by Marc Chagall.

Following the Russian Revolution, Shchukin’s and Morozov’s art collections were confiscated by the state. Shchukin fled Moscow for Paris in 1918 where he died in 1936. Morozov stayed in Moscow for another year, wanting to watch over his collection. He accepted the position of deputy director of his former collection. He was granted permission to live, with his family, in three rooms of his former mansion. That didn’t last long. Ivan made it out of Russia, illegally crossing at the border with Finland. He and his family made their way to London then headed to Paris. He died in 1921, at the age of 49, of a heart attack.

After Morozov left Moscow, his French collection was divided, along with Shchukin’s, between the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. The paintings were eventually put into storage, where they stayed for decades. Given how much Stalin hated western art, it could have been worse. He could have ordered more of the paintings sold or some or all of them destroyed. After Stalin died in 1953, the works began to reappear. But even as recently as 2014, when the Vuitton Foundation curators and conservators started preparing for this exhibition, the paintings on the walls of the Hermitage and Pushkin had no indication of provenance. The paintings were there, but no mention was made of how they got there.

The Fondation Louis Vuitton’s efforts, in preparation for these exhibitions, were Herculean. Many of the paintings were in a woeful condition, in desperate need of conservation. With the temporary conservation labs the Fondation set up in Russia, the paintings received the professional care they needed, thus insuring, from that standpoint at least, they won’t disappear. By separating the two collections for these exhibitions, a fuller sense of each collection and each collector was established.

But the curator of both exhibitions, Anne Baldassari, was aiming for even more. For example, one of her goals for the Morozov exhibition, was to introduce Parisian museum goers to Russian avant-garde painters. “I wanted to show connections between the Russian and the European avant-garde,” she said…”each gallery has some Russian art. And the show opens with a series of portraits by Russian artists of the Morozov circle…” By juxtaposing Russian and Western modern art, in an exhibition that celebrates a Russian collector, a taste of pre-revolutionary Russia is ours.

These two collectors and their collections have come alive because of these exhibitions at the Fondation Louis Vuitton and the recent biographies of both collectors, written by Natalya Semenova and published by Yale University Press. Which seems to me to be the least that university press could do, given that the university ‘owns’ a $200 million painting by van Gogh. Stolen by the Soviet government, purchased by Stephen Clark, and bequeathed to Yale, his alma mater.

Bibliography:

The Collector: The Story of Sergei Shchukin and His Lost Masterpieces, Natalya Semenova & André-Marc Delocque-Fourcaud (2018)

Morozov: The Story of a Family and a Lost Collection, Natalya Semenova (2020)

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.