Hold the cream, please…. no wait

Chateau de Chantilly & Musée Condé

Chateau de Chantilly

As museums begin reopening all over France, we are going on another field trip, this time to the Chateau de Chantilly. A fabulous chateau with gorgeous grounds and an amazing art collection. To get here, just go to the Gare du Nord. The train trip to the station closest to the chateau is less than 1/2 hour. Take a bus or taxi or walk to the Chateau. Easy peasy!

Fingers crossed the Chateau will still be open when you get here, because it is having a particularly difficult time, financially speaking. Even more than most other French cultural institutions. Because of the Aga Khan. What? Let me explain. Until 2005, the Institut de France managed the chateau. Then the Aga Khan, who has a property nearby, offered to create a private foundation to run it. The institute agreed. The arrangement was supposed to last 20 years. Between 2005 and 2020, the Aga Khan’s foundation spent more than 70 million euros on the chateau. The goal was for the chateau to be run like a business, for its income to cover its expenses. It was a unique model in France, inspired by the cultural trusts that finance American museums.

But in 2020, the Aga Khan, citing personal reasons, ended his foundation’s involvement with the chateau, five years ahead of schedule. That decision couldn’t have come at a worse time. Especially since the chateau’s eligibility for emergency aid from the State isn’t the same as for state-run museums. Never mind, Scarlet, tomorrow is another day.

Let’s enjoy the art collection and the period rooms at the Chateau while we can. The quality of the art collection is heralded as second only to the Louvre. That kind of hyperbole is often written but rarely merited. In this case, it is. After we soak up the culture in the museum, we’ll wander outside because we will have chosen a warm, sunny day to visit. And as poofs of cumulous clouds make their languorous way across an otherwise eggshell blue sky, we’ll take a break before we explore the exquisite formal French gardens designed by André Le Nôtre. And for our break, we’ll choose the loveliest spot in the garden to enjoy a decadent dessert of creme Chantilly which despite its name, was not invented here. But here was where the famous chef François Vatel committed suicide when the fish didn’t arrive on time. Chefs are delicate creatures but in his case, it is almost understandable - 2000 guests for a party honoring Louis XIV and the fish doesn’t show up. Really, who needs that kind of aggravation.

Figure 1. Photograph of Duke d’Aumale, 1860s

But first, let’s get to know the chateau’s final owner, the one who bequeathed it and his art collection to the Institut de France, the Duke d’Aumale. (Figure 1) Born Henri-Eugène-Philippe-Louis d’Orléans, in 1822, at the Palais Royal in Paris, he was the 4th, or maybe the 5th son (sources differ) of the last king of France, King Louis-Philippe (you remember, le Poire created by cartoonist/caricaturist, Charles Philipon). (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Louis-Philippe as the poire, Philipon, 1831

The Duke inherited Chateau de Chantilly when he was 8, from his godfather, Louis-Henri-Joseph de Bourbon, the last Prince of Condé. He inherited it because the Bourbon-Condé line ended when his godfather’s son, the Duke of Enghien, was executed at the Chateau de Vincennes by order of Napoleon in 1804.

In 1837, the Duke d’Aumale joined the French army at the rank of captain. In short order, he married his cousin, Princess Maria Carolina Augusta of Bourbon-Two Sicilies and became Governor General of Algeria. A position he held very briefly because another French Revolution, the one of 1848, got in the way of his happy ascent through the military ranks. And he had to put on hold his project to rebuild the Grand Chateau at Chantilly, which had been destroyed during the first French Revolution.

With other members of the extended royal family, he fled his homeland for London where he lived in exile for the next 23 years. He spent his time and his money admirably, acquiring paintings and decorative art objects, books and manuscripts, eventually amassing one of the most important private collection of paintings and drawings now in France. One of his goals was to buy back as much as he could of what had been taken and sold during the French Revolution, works by French masters like Poussin, Ingres and Watteau and Italian masters like Botticelli, Raphaël and Titian. This is a little confusing because one source suggests that he was so strapped for money, it was only through his wife’s friendship with Queen Victoria that he and his family had a proper home to live in, Orléans House in Twickenham, outside of London. The Duke’s motto became:"I will wait". Which was a good motto, since he did.

When he returned to Paris in 1871, his wife was dead, all of his children were dead, too. Of the 7 children his wife bore, 3 were stillborn, 2 died in infancy, one of the two sons who survived childhood died at age 18, the other died at age 21. Geez, if Toulouse Lautrec’s cautionary tale for why avoid marrying a close cousin doesn’t convince you, then this story of dead babies should.

The Duke’s return to France lasted only 15 years. He was forced to flee a second time in 1886 when a law was passed expelling the heads of former reigning families. The law further stipulated that all members of those families were disqualified from holding any public position or function or elected to any public body.

It was those series of laws that infuriated the Princess Galliera, as you’ll remember from my post about the Musée Galliera, the fashion museum of Paris. Instead of donating her art collection to the museum she built in Paris to house it, she took her art back to Genoa with her. And gave the Hotel Matignon, now the official residence of the French Prime Minister, to the Austro-Hungarian Empire for its French embassy.

The Duke d’Aumale didn’t return to England in 1886. Instead, he moved to Zucco, in Sicily, Italy, where his family had roots. Where he bought a wine estate and with the knowhow he brought with him from France, began producing wine, very high quality wine. Which has recently been revived. To learn more about the wine, click here.

The Duke of Aumale died in 1897. The description of his death is kind of sweet, if one can use such a word to describe such an event. He had decided to write condolence letters to the families of all the aristocratic ladies who had been killed in the fire at the Bazar de la Charité in Paris that year. The Bazar was an annual charity event organized by French Catholic aristocracy. The decorations that year were too flammable, the exits too poorly marked and too many avoidable deaths resulted. After finishing his 20th letter of condolence, the Duke suffered a massive heart attack and died. Of course, as I tried to further understand why he would take such a task upon himself, I discovered the following. The Duke may have actually been mourning women he knew, intimately. The Duke was, as they say, un chaud lapin. A sexual position was even named after him, one which is also variously called the Andromache position (named after Hector’s wife - in the Iliad) or Cow Girl position. Use your imagination, or google it, like I did.

In his will, written just a few months before his death, he bequeathed his Chantilly estate to the Institut de France, with the stipulation that his extensive collection was to be turned into a museum open to the public, which it was a year later. The bequest also stipulated that the layout of the collections was to remain unchanged, that nothing could be lent or sold. So the château that we visit today looks very much as the duke left it. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. The Tribune. Musée Condé, Chateau de Chantilly

When I walked through the museum for the first time, I felt as if I was visiting old friends. So many paintings that I have known forever, that are in all the standard Art History survey books. The kind of paintings you expect to see at the Louvre or the Met or one of the National Galleries (London or Washington) but not in some fantastic chateau just outside of Paris.

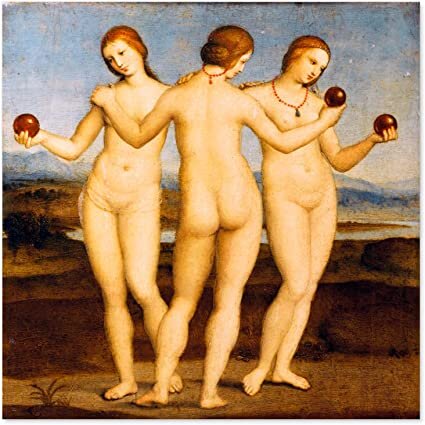

Here’s what I mean. Raphael’s Three Graces (Figure 4) painted in 1504 is a small painting but one of the most important in the collection. We saw Maillol’s interpretation of this classical Greek theme a couple weeks ago. An X-ray of Raphael’s painting shows that he originally intended it as a Judgement of Paris with only one goddess, the most beautiful of all, holding the apple. But he changed his mind and put a golden ball in each goddess’s hand. And voila, they became the Three Graces.

Figure 4. The Three Graces, Raphael Sanzio, Musée Condé, Chateau de Chantilly, 1504

Figure 5. Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci, Piero de Cosimo, Musée Condé, Chateau de Chantilly, 1480

Piero de Cosimo’s portrait of Simonetta Vespucci from 1480 (Figure 5) is another one of those paintings in all the Italian art history survey books. She was Botticelli’s model and she died at age 23. This posthumous portrait of her is a memorial commissioned by one of Lorenzo the Magnificent’s brothers.

A painting of the Massacre of the Innocents by Nicolas Poussin, (Figure 6) is just as important. Most depictions of the murder of all boys aged two and under, ordered by King Herod, in an effort to kill the newborn King of the Jews, are chaotic assemblages of thrashing bodies - soldiers hacking, babies flailing, mothers wailing. This painting highlights one of each (although there is a second wailing mother behind) and the pain and suffering is palpable. Three colors, red, yellow, blue and one X, the center of which is the face of the screaming mother, further intensifies the horrific moment.

Figure 6. Massacre of the Innocents, Nicolas Poussin, Musée Condé, Chateau de Chantilly, 1629

Okay, just one more, of my favorite girl, Gabrielle d’Estrées, (Figure 7) Henri IV’s mistress, who we met last week. Here she is again, still in her bath, but this time with two of her and Henri’s sons, one of whom, dressed in swaddling, is being suckled by a nursemaid. You didn’t think society women breastfed their own children, did you? The composition is very similar to a portrait of Diane de Poitiers, (Figure 8) the mistress of Henri II. What infuriates me about portraits of nude women is that the portraits were created for the delectation of men and then a mirror is added or an hour glass to accuse the women either of vanity or remind them of the fleeting nature of beauty. Grrr.

Figure 7. Portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées, School of Fontainbleau. Musée Condé, Chateau de Chantilly, Late 1590s

Figure 8. Portrait of Diane de Poitiers at her bath, Fontainbleau School, ca 1550s

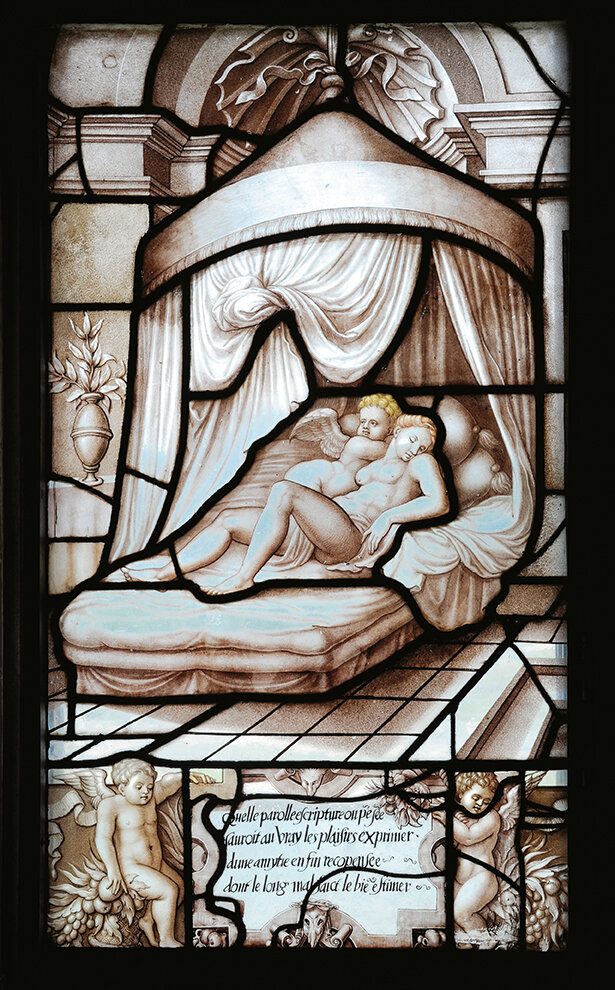

The last time I went to Chantilly, I couldn’t pull myself away from the Psyche Gallery, 44 stained glass windows in grisaille (gray), created in 1542. (Figure 9) The panels depict the story of Cupid and Psyche and their forbidden love. You remember Cupid from Bronzino’s painting last week, tweaking his mother’s nipple. Well, in this story he does more than tweak Psyche’s nipples. The panels were created for the Château d’Écouen, the French National Renaissance Museum. Which is closer than Chantilly and also accessible by train. If you haven’t been, you should go, now.

Figure 9. Cupid and Psyche, stained glass, Psyche Gallery, Chateau de Chantilly, 1542

Also, the last time I was there, I saw a fabulous temporary exhibition on porcelain from the Meissen and Chantilly collections. It told the story of two men, the Elector of Saxony (Meissen) and the Prince de Condé, who were obsessed with porcelain. Their incredible collections, on display here, were the result of that obsession. (Figure 10)

Figure 10. La Fabrique de l’Extravagance, Exhibition Catalogue, Chateau de Chantilly, 2019-2020

In addition to the painting collection we have just been discussing, there are private suites, public suites (where the porcelain exhibition was presented) and a reading room. All of which are lavishly decorated with magnificent furniture covered with sumptuous fabrics. The walls and ceilings are also delightfully painted (Figure 11). The reading room displays 19,000 of the Duke’s 60,000 manuscripts and books. The most important, or at least the best known is the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, by the Limbourg Brothers, which we saw a few months ago. My favorite scenes are January and February. In one, the king behaves decadently, in the other, the simple folk behave indecorously. (Figure 12)

Figure 11. Grand Salons, Chateau de Chantilly

Figure 12. Calendar Pages, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Limbourg Brothers, Musée Condé, Chantilly

Now the gardens, which are every bit as marvelous as the chateau itself. There are three styles of gardens at Chantilly, French, English and Anglo-Chinese. Of course I prefer the formal French gardens designed by Le Nôtre in the 1660s (Figure 13) which were completely restored in 2009, thanks to the Aga Khan. Like all French-style gardens, this one has a geometric, symmetrical layout, made up of flowerbeds, groves and ponds, dotted with statues and animated by water features. The reason I like these French gardens is because they celebrate the triumph of order over disorder, of culture over nature.

Figure 13. Aereal view, Formal Gardens of Domain de Chantilly, André le Nôtre, 1660s

The Anglo-Chinese garden was created in the 18th century when all things Chinese, chinoiserie, was the fashion. It includes several small structures, among them, five small houses, a hamlet if you will, (Figure 14) which inspired Marie-Antoinette’s Hamlet in the Petit Trianon at Versailles. (Figure 15) As soon as it was created, the Anglo-Chinese garden became one of the main attractions of the grounds. A place for refreshments and entertainment. And that is exactly where the pavilion I went to enjoy a treat made using Chantilly whipped cream, was located. (Figure 16) There is an English style garden, too. Le Nôtre wasn’t a fan and neither am I. All that (seemingly) untamed wilderness? I could have stayed in California for that. Thank goodness for the folies that inject a much needed bit of artificiality. (Figure 17).

Figure 14. Hamlet, Anglo-Chinese Garden, Domain de Chantilly

Figure 15. Marie Antoinette’s Hameau, Petit Trianon, Versailles

Figure 16. Restaurant serving Chantilly Cream, Anglo-Chinese Garden, Domain de Chantilly

Figure 17. English Garden, Domain de Chantilly

UPDATE: new photos from July 2023:

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!