Finding our way

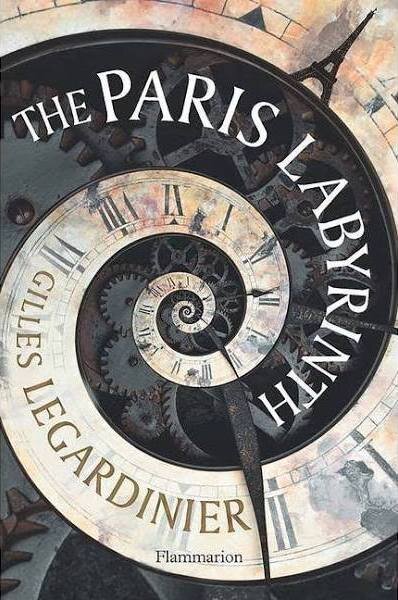

The Paris Labyrinth by Gilles Legardinier

Today I am going to talk about The Paris Labyrinth by Giles Legardinier, the English translation of the author’s 2019 book, Pour un instant d’eternitie. Although his 20+ books have been translated into 20+ languages, English has not been one of them, yet. His publisher is hoping this one is the first of many. I’m guessing it will be. Tracking down and confirming all the historical information in the book was definitely hard work and the author didn’t do it alone. His daughter, Chloé is given credit for “Research and Documentation”. Bravo!

This is not going to be a book jacket kind of blurb or a couple sentences a la Publishers Weekly or a jam packed paragraph a la Kirkus Review. Since it is me, it is going to be on the longish side, with a few detours during which art and history and Paris will be discussed.

The book is mostly a really good mystery, but you must be willing, at a moment’s notice, to suspend your disbelief and welcome in the supernatural and the occult, too.

The protagonists of the tale are four men, each of whom brings a particular skill set, a specific expertise to their joint projects, which are the creation of secret rooms or secret passages for people who have something (a treasure perhaps) to hide or who want to hide themselves. The trompe l’oeil painter is Italian, the burly woodworker is German and the main character Vincent, is a Paris born mechanical virtuoso who devises the intricate mechanisms that open and close and hide those secret rooms and passages. Vincent’s younger brother helps him as does a young boy, an orphan, who the gang has taken in.

Theirs is a tricky kind of profession. I mean, if you want a secret room and you are willing to pay somebody a lot of money to create it, then you want a room that is truly secret. And wouldn’t you naturally want to eliminate anyone who knew about your secret room, anyone you couldn’t control? And wouldn’t that be specifically the people who created that secret room? Of course it would.

I am watching the 4 part series, ‘This is a Robbery,’ about the theft of all those masterpieces at the Isabella Stewart Gardiner Museum in Boston in 1990. The chief thief suspects were found murdered in part 3. Dead men tell no tales, more specifically they don’t tell anybody who hired them to steal paintings or where those paintings are or in this case, where your secret room is. So these four guys have dangerous jobs and for safety reasons, have very little contact with the outside world. Their residence, in Montmartre, is more or less hidden in plain view and accessed through a secret passage (of course). They work underground in a large vaulted space, the former wine cellars of a former royal abbey, which is accessible through rue Caulaincourt, a street that was/would become the residence of many artists, like Toulouse Lautrec, Modigliani and Renoir.

The Labyrinth-like Montmarte, where the charachters live. Photograph by Ginevra Held.

The story, or actually stories at the center of this book, focus on two men (each with entourage) who approach Vincent and offer him and his colleagues an intriguing job. Neither man wants Vincent to create a secret room. Each wants Vincent to find and access already existing secret rooms and the passages that lead to them. Vincent has to decide which man to trust, which man he should join forces with and which man has nefarious intentions and will become the antagonist in this tale. Vincent hedges his bets and doesn’t get it right at first. And then he and his small band become the target of assassination attempts that are increasingly more violent and more graphically described. I skipped a few paragraphs every so often when the descriptions got too much for me.

Safe Surrender Sight, Local Firehouse, San Francisco.

Abandonment and loyalty are recurring themes in the book. So, I decided to see if it might be biographical. Legardinier’s very brief Wikipedia page offers intriguing clues. Firstly, he was abandoned as an infant in front of a chapel in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. Wow, that’s a conversation stopper. In San Francisco, on the way to my weekly farmers market, I pass a fire station, on a door of which is written ‘Safe Surrender Site,’ with a graphic of an infant. When I walk by, I always think of Hogarth’s portrait of Thomas Coram the philanthropist who created the Foundling Hospital in London or the sculpted roundels of bambini by Luca della Robbia on the foundling hospital, the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence. Now I will have another pensée, Giles Legardinier abandoned as an infant, in front of a chapel in the chic part of Paris. I wonder if his mother lived in the 6eme or figured her newborn would have a better chance if she abandoned him there rather than in the (I’m guessing here) banlieu where she lived.

The Foundling Hospital, London. Photo by Ginevra Held

Thomas Coram founder of Foundling Hospital, London. Photo by Ginevra Held.

Vincent and his brother Pierre are orphans, not abandoned by their parents by choice but by violent death and illness. Their mother didn’t have enough money to give their father a proper burial and they didn’t either when she died. The two brothers are bound by a shared grief and an intensely powerful bond.

The second bit of information in Legardinier’s very brief bio is that he did not complete his baccalaureate (national high school exam), which in France is a very big deal. According to the Christian Science Monitor, “Passing the exam assures entrance to almost any university… (F)ailure leaves a stigma for life, a second-class citizenship socially as well as educationally.” Legardinier doesn’t seem to feel stigmatized by his failure. The English playwright Tom Stoppard never went to college either. I’m guessing Legardinier and Stoppard are probably the most erudite guys in any room they enter.

Legardinier’s lack of formal education is another tie-in with the protagonist of this story, Vincent, who learned his craft from a master who taught him out of kindness since Vincent had originally been the boy who delivered coal each morning. And it explains too, Vincent’s patience with the young boy Henri. Without any preparatory education, Henri’s dream is to become a doctor. While the others laugh, Vincent encourages him.

A recurring interaction in the book is between Vincent and a deformed dwarf who Vincent sees ‘performing’ one day and who he visits regularly thereafter. The dwarf is called Quasimodo, like the hunchback in Victor Hugo’s tale. In Hugo’s tale, the deformed Quasimodo had been abandoned in Notre Dame, on the foundling bed, where orphans and unwanted children are taken, with hope that the public will care for them. Quasimodo was abandoned on the Sunday after Easter Sunday, called Quasimodo Sunday.

What finally happens to the misshapen creature in this book is very different from what happened to Hugo’s Quasimodo, very different from what happened to the handicapped young man in the short film the Coen brothers wrote called "Meal Ticket”. Did you see it ? An old guy played by Liam Neeson drives from town to town with a young man who has neither arms or legs. At each town, the young man recites classical poetry for a few coins. At one town, the old guy sees a performing chicken, a chicken who counts. He buys the chicken. Crossing a river on the way out of town, the old guy drops the armless, legless man from the bridge into the river and drives off with the chicken. Chilling, creepy.

So I wondered if Legardinier had any personal experience with handicapped or ‘different’ people. And I came upon a short video in which Legardinier and Mimi Mathy, a French comedienne who is a dwarf, discuss a book they had just written (2017) entitled, ‘Is it better to be very small or abandoned at birth?’ I haven’t read the book but it’s a good question, which is better (or worse) to have a difference people can see or one they can’t see.

Has this ever happened to you ? You come upon a name or phrase and all of the sudden that name or phrase is everywhere. Here’s an example of what I mean. When I was home schooling my son, he saw the film Troy (he was 9) and he became obsessed with the Odyssey, which we read, over and over again. For one of his adventures, Odysseus has to choose between Scylla and Charybdis, between sacrificing some of his sailors or risking the loss of his entire ship and crew in a whirlpool. And then it seemed as if every book or article I read included an impossibly difficult decision that was always described as a choice between Scylla and Charybdis. I haven’t read the Odyssey for a while and I haven’t come upon Scylla and Charybdis either.

This time, in this book, it wasn’t quite as intellectual. I recently wrote about the gallerist Berthe Weill, whose father had been a ragpicker, as had Bernard Berenson’s father, who I also wrote about and Kirk Douglas’ father, to whom I had referred. And I mentioned in the Weill article that the trade disappeared in France when Eugène Poubelle came up with the idea of providing public trash bins. I also read somewhere that another name for ragpicker is rag and bone man (Rag and Bone is also the name of a cleverly self deprecating high-end fashion house, and also a delightful tune by The White Stripes- the more you know). Chapter 4 of this book begins, “The rag-and-bone men were already going about their business, cursing the Poubelle bins that were stealing their livelihood.” And if you didn’t know that a rag and bone man was a ragpicker and if you didn’t know that Prefect Poubelle was the one with the idea of providing public trash bins and if you didn’t know that the French word for trash bins is poubelle (why wasn’t it translated?), well, that sentence would have made absolutely no sense to you. Or less sense than it makes now. You’re welcome.

The book is also a little ‘Ragtimey’, by which I mean that like the book Ragtime, most of the characters are fictional but they are interwoven with actual historical figures and the places they lived or worked or buried their treasures. For example, Vincent often sits at the grave of his mentor. Etienne Begel who had been trained by Charles Houdin. Begel is a fictitious person but Robert-Houdin is not. He was a watchmaker, magician and illusionist who transformed the art of magic. After Robert-Houdin it was no longer an idle amusement for the poor but a sophisticated entertainment for the wealthy, (aka Penn and Teller). Did you know that Harry Houdini, (né Ehrich Weiss) was so impressed by Robert-Houdin’s work that he changed his stage name to Houdini?

Much of the book’s action takes place on what is now rue du Temple in the Marais where the Knights Templar are believed to have buried their enormous treasure beneath a fortified compound that is no longer there. Nicolas Flamel, the celebrated alchemist may have purchased a house nearby to watch over or gain access to the buried treasure that also lures Vincent’s final clients. Flamel’s house is still there, the oldest house in Paris.

As I read the book I enjoyed coming upon streets, like the rue du Temple, that I have known and walked along for years and learning more about them. And I enjoyed bumping into streets that I have only recently come upon, in my constant walks, as I bide my time waiting for the museums to open, like rue Victor-Massé where Berthe Weill had an art gallery, and rue Gravelliers where I had lunch at Terrance’s.

And since the action takes place at the end of the 19th century, the Parisian places that are described are ones we have either heard about or visited, focusing mainly in Montmartre. For example, Le Chat Noir, (the iconic poster for which we are all familiar) celebrated as the first modern cabaret - where patrons sat at tables, drank alcoholic beverages and watched live entertainment. There was also a shadow theater that became enormously popular and which called upon the talents of many of those who frequented the cabaret, the writers who wrote the stories, the artists who created complex color and movement effects and the pianists who played the accompaniment.

Or the Lapin Agile, another Montmartre institution that makes several appearances in the book. Steve Martin wrote a play about an imagined meeting there between Picasso and Albert Einstein. The Lapin Agile is first referred to in this book as Au rendez-vous des voleurs and then as the Cabaret des Assassins and then by the name it still holds, Lapin Agile. And that was a bit confusing, so I looked it up and indeed this cabaret has had all three of those names sequentially. The final name Lapin Agile began as Lapin a Gill, after the artist Andre Gill who painted the cabaret’s sign. When museums finally open up here, I am going straight to the Musée Carnavalet which has been closed too long and which has a wonderful collection of enseignes, shop signs, by which people navigated the City before street names and numbers.

Sacré-Coeur, the majestic domed church at the summit of the butte Montmartre, the highest point in the city plays an important role in the story, too. It is where Vincent comes to sit and think and plan as he looks down at the city of Paris. Did you know that construction on Sacré-Coeur began in 1875? And it wasn’t completed until 1914? Since this book takes place in 1889, the church is just a chantier, a building site and not a welcomed one either. The residents, who are all poor are all being displaced by the monstrosity that just kept growing. Well, you can’t make an omelette without breaking some eggs. And you can’t build a grand boulevard without destroying some medieval houses, and you can’t construct a grand church without doing the same. Sacre Coeur is now a white beacon on the hill which people flock to see. But of course it wasn’t always a beloved monument, not by a long shot.

The majestic Sacre Couer. Photo by Ginevra Held.

The action in the book takes place in 1889, the year of the Exposition Universelle, the 4th to be held in Paris. (The first was held in London in 1851, think Crystal Palace. The next one is scheduled for this fall in Dubai). The year 1889 was selected to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the start of the French Revolution. Awkward date for some of France’s European neighbors, specifically those with monarchies who officially boycotted the Exposition.

The main Exposition site was on the Champs de Mars, where one could visit the Eiffel Tower and Palace of Machines. The Eiffel Tower, the tallest structure in the world at the time, was built for the Exposition and was intended to be temporary. Eiffel won the competition because his company had already designed a tower exactly to this one’s dimensions. Like I.M. Pei’s pyramid for the Louvre and Jeff Koons’ Bouquet of Flowers, the Eiffel Tower was roundly denounced by artists and critics when it was first built. Beloved landmark these days.

La Tour Eiffel. Photo by Ginevra Held.

The Italian trompe l’oeil artist was the first in the book whose life was threatened at the Exposition. When he and the Countess, good side story, you’ll enjoy it, were first attacked, they both assumed their attackers were thieves after her jewels. No, it was assassins after him. Sloppy assassins, they thought they had succeeded when they fled as help arrived.

Another site of an attempted assassination of one of Vincent’s colleagues is the Gallery of Machines which covered the longest interior space in the world at the time and which cost 7 times more to build than the Eiffel Tower. That attack was so brutal I had to skip a few pages. So you are on your own to see how that one went down. And how the other attempts played out, the ones that were foiled and the one that succeeded and how that changed Vincent’s life.

Just in case you require a book jacket blurb, here it is, paraphrased, “This tale is about an ingenious illusionist Vincent who embarks upon a thrilling adventure to unlock the mysteries of the past in a quest for lost treasure. Along the way, he battles against dark forces as he tries to discern who he can trust. As Paris celebrates the 1889 World's Fair, Vincent’s team become the target of multiple assassination attempts. They puzzle over who could be the faceless adversary, lurking in the shadows, ready to strike them anywhere, anytime. Confronted with mysteries uncovered from the past, Vincent does everything in his power to thwart the menace and protect his friends.” This is a great read, especially for Paris lovers like us.

To enjoy more photos of Paris click here.

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved