A Master and his Muse

Part 1: Aristide Maillol, before the Muse

Musée Maillol

I have been meaning to write about the sculptor Aristide Maillol and the museum that bears his name for a while. Finally, here we are and honestly, I never expected to discover so many fascinating and provocative ‘facts,’ some of which may even be true !

Figure 1. Esprit es-tu là?, Musée Maillol, Paris

I have been coming to this museum more or less regularly for the past several years because Culturespace, the group which creates the content for the Atelier des Lumieres and the exhibitions for the Jacquemart Andre Museum has, until this January, created the exhibitions for the Maillol, too. I have seen an excellent exhibition on Giacometti, a fascinating one on the Japanese artist Foujita. The exhibition, ‘Espirit es tu la’, was also at the Maillol, I wrote about that one last summer. (Figure 1)

Mounting temporary exhibitions at house museums dedicated to the collections of single patrons, like the Jacquemart-Andre or single artists, like the Bourdelle, is not the same as mounting temporary exhibitions at museums where rooms can be emptied and works temporarily put in their place. Something more has to be done, some other accommodation has to be made, to the permanent collection which is the raison d’etre for the house museum’s existence. The Bourdelle Museum temporary exhibitions are selected because they, in some way, incorporate or enhance the permanent collection. This is not the case with the Jacquemart-Andre where rooms are emptied for the purpose. But there, at least, you walk through some of the marvelous treasures that Nellie Jacquemart and her husband Edouard Andre, collected. The collectors’ collections still matter.

Temporary exhibitions at the Maillol are held on the ground floor and lower level. If you want to see Maillol’s work, you mostly have to walk upstairs. Which I usually do. And I have usually felt a little uneasy seeing photographs of a very young girl and the painted and sculpted depictions that the artist made of her when he was a very old man. Now that I know more, I am going to feel less uncomfortable next time I am there, A little knowledge goes a very long way. And the next time I am there may be soon, since France is scheduled to reopen later this month.

Before I tell you about Dina Vierny, the young girl who is the subject of the photos, the paintings, the statues, I am going to discuss the artist his work. His work, that is, up until the age of 73, when it could be reasonably assumed that an artist might slow down a bit and maybe even concentrate on his legacy. That isn’t what Maillol did. In fact he began a phase of his artistic career (and perhaps personal life) that was rich and very, very productive. Because of Dina Vierny. But we’ll get to that in a little while.

Aristide Maillol was born in 1861, in Banyuls-sur-Mer, in the south of France, in the foothills of the Pyrenees, close to the Spanish border and the Mediterranean Sea, in short, in Catalan. Aristide was the fourth of five children whose father traveled and whose mother manifested such little interest in her child that his father’s family took over the task of raising him. Sent to boarding school for a few years, he discovered painting and not only that, he discovered that he was good at it. Following art classes at a local museum, he left home for Paris, at age 20, to continue his studies. A tiny stipend from his father’s family, his Aunt Lucy, kept him from starving.

After several failed attempts to gain entrance to the École des Beaux-Arts, he was finally accepted. Mais quel déception! (as we say in French). He quickly realized that what they were teaching was not what he wanted to learn. But he was in Paris and it was the 1880s. He saw exhibitions by the Impressionist and the artists who exhibited with them, like Gauguin. Maillol explained it this way,"Instead of enlightening me, the École des Beaux-Arts had thrown a veil over my eyes. ..Gauguin's painting was a revelation to me….”

Influenced by Gauguin and the artists who called themselves the Nabis, among them, Maurice Denis and Edouard Vuillard as well as the Musée Cluny, the museum of medieval art, Maillol’s interest turned to tapestry. He took classes in tapestry design and manufacture. Gauguin’a opinion of Maillol’s efforts was encouraging, "Maillol is showing a tapestry which is beyond praise”.

Maillol returned to his beloved Banyols, eight years after he left, eager to set up a tapestry workshop. Which he did, along the way marrying one of the two women he hired to work with him, the one who was pregnant with his child. As good a way as any to choose! With commissions coming in, he returned to Paris and opened a workshop there. But his tapestry career was cut short. The close work strained his eyes and he was afraid he would lose his sight. So he switched gears again, focusing this time on sculpture, with which he had already begun to experiment.

Living in Paris now, with a small family to support, the pressure must have been enormous and the memories of hunger and want, constant. But at least he had a willing model, his wife. And for the first time, nudes began to appear in his work. Maillol worked initially in wood, then transitioned to bronze which he found suited him perfectly. He began with statuettes, creating 30 small ones in 1900. His first one-man exhibition came two years later, in 1902, at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery. (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2. Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, Pierre Renoir, 1908, Courtauld Inst, London

Figure 3. Crouching Woman fixing her hair, Aristide Maillol, 1900

Maillol’s first success came with his sculpture entitled ‘Seated Woman’ which was exhibited at the Salon d’automne in Paris in 1905. Maillol sculpted a number of variations and iterations of this statue over the years. One version, dated 1900, (Figure 4) and now at the Met, shows a seated female nude in a pose that recalls the Greek sculpture, 'Thorn Picker,’ or ‘Spinario,' (Figure 5) a young boy pulling a thorn from his foot. The version exhibited at the Salon in 1905 has at least two iterations. One, a statuette, of which the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. has a copy in marble, shows a young woman posed with her bent elbow hovering above her bent knee. (Figure 6) In a larger than life size version, in bronze, the young woman has her elbow resting on her knee. (Figure 7) In both, she has a pensive air. The critic André Gide contrasted Seated Woman with sculptures by Rodin in the same exhibition. The Rodin sculptures, Gide wrote were "troubled, significant, full of pathetic clamor"; while Maillol's woman "is beautiful, … silent .… I believe one must go far back in time to find such complete neglect of any preoccupation beyond the simple manifestation of beauty.”

Figure 4. Crouching Woman with crossed leg, Aristide Maillol, 1900

Figure 6. Crouching Woman with elbow and knee raised, Aristide Maillol, 1900

Figure 5. ‘Spinario’ or Thorn Picker, Roman marble copy after Greek bronze original

Figure 7. Crouching Woman with elbow touching raised knee, Aristide Maillol, 1905

In 1905, as the English poet James Fenton, whose funny, snarky and insightful essay on Maillol, tells us, Rodin brought Maillol to the attention of the German aristocrat, Count Harry Kessler. (Figure 8) Kessler was the first to commission a large scale bronze version of Seated Woman. After being called Pensée and a few other names, Maillol decided to call the statue, La Méditerranée, this was in the 1920s, explaining, “I had thought of calling her Young Girl in the Sun; then, on a day of beautiful light, she appeared to me so alive, so radiant in her natural atmosphere that I baptized her La Méditerranée. Not the Mediterranean Sea.…That's not what I was after. My idea in sculpting her was to create a figure that was young, luminous and noble. …the essence of the Mediterranean spirit.”

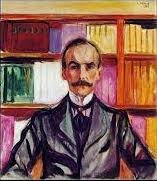

Figure 8. Both of these are by Harry Kessler, by Edvard Munch, 1906

That Rodin introduced Maillol to Kessler, to a potential client is pretty interesting as egos go. But there was no bad blood between Rodin and Maillol. Rodin didn’t feel as if Maillol was trying to copy his work, to steal his ideas. Maillol had never worked for or with Rodin (as Camille Claudel and Antoine Bourdelle both had). Maillol and Rodin weren’t on the same wavelength. In fact, of course, Maillol was one of the first modern sculptors to react against the emphasis on emotions that characterized the sturm and drang of Rodin’s sculpture. Maillol preferred the serenity and sculptural tradition of Classical Greece.

Figure 9. Rodin’s Thinker & Maillol’s Méditerranée

Rodin may have been sanguine about the younger sculptor, not perceiving him as a threat, but Maillol went to lengths to establish the difference between himself and Rodin. As Fenton points out, Maillol’s letters over the years to Kessler, emphasized those differences. There was an exhibition in Perpignan a couple years ago entitled “Rodin-Maillol Face to Face” . And the exhibition did indeed put Rodin’s iconic Thinker next to Maillol’s Méditerranée, (formerly known as Pensée,’ ’Thought’). (Figure 9) Rodin is more intense, Maillol is less fraught. The same can be said with any other set of comparisons you might wish to provide to compare the two, like Maillol’s Pomone (Figure 10) and Rodin’s Eve (Figure 11) or Maillol’s Three Nymphs and Rodin’s Three Shades (Figures 12).

Figure 10. Pomone, Aristide Maillol, 1907

Figure 12. Foreground Three Nymphs, Maillol,1930, Background The Three Shades, Rodin, before 1886

Figure 11. Eve, Rodin, 1881

When I taught Italian Renaissance art at Stanford I used to compare Giotto’s fresco of Anna and Joachim (Virgin Mary’s parents) from the Arena Chapel (Figure 13) with Brancusi’s The Kiss, (Figure 14) as a celebration of the essence. I would contrast both with Rodin’s sculpture of the same name. (Figure 15) Celebrating essence, dismissing overstatement. I had to be careful because the Rodin scholar Al Elson was a colleague and he could have walked by at any moment. But I think if I was teaching that course now, I would show a little more of the journey from Rodin to Brancusi by making a stop at Maillol.

Figure 13. Anna and Joachim at the Golden Gate, Giotto, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1306

Figure 14. The Kiss, Brancusi, 1907-08

Figure 15. The Kiss, Rodin, 1882

In 1908, Kessler and Maillol travelled to Greece. They were definitely a study in contrasts. Kessler was the elegant son of a wealthy Prussian industrialist. A repressed homosexual, he poured his passion into collecting art and supporting artists, no demands made. Maillol was a peasant; basic, even boorish, disappearing every time the waiter brought a bill. Of course he did, he had fended off hunger for too many years to start grabbing for the bill, any bill, especially when traveling with an aristocrat whose wealth was just as inherited as Maillol’s poverty had been. Fenton paints the picture of the rustic Maillol, whose lusty enthusiasm for women must have gotten in the way of Kessler’s aesthete cruising for young men. They both wanted to find models to pose nude, but one wanted his models with big bottoms and high breasts, the other was looking for the Charioteer, or perhaps the Discus Thrower. (Figure 16)

Figure 16. Discus Thrower, Myron, 450 B.C.E.

Maillol’s trip to Greece was a pilgrimage to the land of his true artistic ancestors. And his real ancestors, too. The part of France where Maillol was born and with which he identified throughout his life had been first settled by the Greeks, the Phoenicians, in 400 B.C.E. Classical, pre-Hellenistic sculpture confirmed his own ideas about what sculpture should be.

There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, that Maillol rushed to embrace one of the caryatids of the Erechtheum when he was in Athens. (Figure 17) But the Greek sculpture Maillol loved best was the sculpture of Olympia. (Figure 18) He wrote, “I prefer the still primitive art of Olympia to that of the Parthenon. It is the most beautiful I have seen, more beautiful than anything else in the world. It is an art of synthesis, an art superior to our modern art which seeks to represent human flesh.” Maillol didn’t seek to represent human flesh in his work, it was Rodin’s statues that Maillol was speaking about, that he was contrasting with the pure statuary of the ancient Greeks, his own artistic roots.

Figure 17. Caryatids on Erechtheum, Acropolis, Athens, Greece, 420 BCE

Figure 18. Apollo, Temple of Zeus, Olympia, Greece, 450 BCE

Maillol, according to Fenton, once said that he “could imagine his figures rolling around on the ocean bed, ground down by the action of water and sand, until they reached their essential form, after centuries of abrasion. Such a process would, he thought, destroy the essence of a Rodin, but reveal the essence of a Maillol.” Rodin’s statues would lose all their details, while Maillol’s would survive as he had sculpted them, worn down maybe, but just as smoothed and rounded as he created them, their essence intact. I am reminded of the Riaci bronzes, two full size Greek bronzes of naked bearded warriors, cast about 450 BCE which were discovered near Riace, Calabria in southern Italy in 1972. (Figure 19) They had spent at least 2000 years in the salty Mediterranean Sea and they still look pretty good to me!

Figure 19. Riaci Bronzes, Greek, 450 BCE

Figure 20. Liberty in Chains, Tuileries Garden, Aristide Maillol, 1906

Maillol’s figures are all sturdy and solid and nude. And female. And it didn’t matter what the commission was for, if you asked Maillol to commemorate something, you were going to get one of his Jane Russel full-figured gals. There is a story about Maillol’s commission for the memorial to the French revolutionary leader Louis Augueste Banqui. Maillol was approached by the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. The sculptor asked what sort of man he would be commemorating. Clemenceau told him all about the years Banqui had spent in prison for his ideals. After he was finished describing the man to be memorialized, Clemenceau asked Maillol what kind of statue he thought he would create. “I’ll make you a nice big woman’s ass and I’ll call it Liberty in Chains.” (Figure 20) Apparently Clemenceau was delighted. I guess he liked his women on the zaftig side too. Liberty in Chains is a portrait of his wife, Clotilde. When committee members charged with the task of overseeing the memorial asked about it, Maillol is said to have replied that his wife was better looking than Blanqui had been anyway.

Figure 21. David. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Marble, 1623-24

Maillol's interest was not with the living, breathing person on pause, the ideal that Rodin had inherited from his predecessors like the Baroque artist, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. (Figure 21) No, Maillol’s focus was on a ”pure sculpture based on the body's architecture and on a harmony between volumes” the cube, the triangle, the lozenge. Indeed, Maillol is the link between ancient Greek sculpture and abstract sculptors like Constatin Brancusi and Jean Arp, with whom he shared an interest in the geometry of form. Maillol’s large bronzes also paved the way towards greater simplification, as in the sculptures of Henry Moore. (Figure 22). Maillol’s contribution to abstraction can be traced through Cubism and towards the pure forms of contemporary artists like Anish Kapoor (Figure 23) and Isamu Noguchi.

Figure 22. Reclining Figure, Henry Moore, lead on oak base, 1939

Figure 23. Cloud Gate, Millennium Park, Chicago, 2006

And what about Kessler, his companion on his Greek trip? Maillol’s and Kessler’s friendship endured after they returned from Greece. In addition to continuing to purchase and commission sculptures, Kessler founded his own printing press and frequently commissioned Maillol to create drawings for his publications. Maillol's frustration with the paper he was working with led him to design and produce his own. In 1913, with Kessler’s backing, Maillol began to produce his own paper, called "Montval" which is still available today. In the early 1930s, Kessler fled his own country for France. He died without his fortune in 1937.

That same year, Maillol received a letter from an architect friend of his telling him of a young woman he had met, Dina Vierny, who strongly resembled his ideal figural type. Maillol wrote to Vierny immediately, "Mademoiselle, I am told that you look like a Maillol or a Renoir. I'd settle for a Renoir". Their relationship during the last decade of Maillol’s life and Vierny’s own adventures after Maillol’s death will be the topic of next week’s review. See you then.

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved