Nursing Mothers, Girls in Cars and Men Bathing

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. A quick update before I get to the two exhibitions I want to tell you about today. Since I’m flying back to Paris on Wednesday, this past week has been a flurry of activity. We saw the exhibition on K Pop at the Asian Art Museum. It was both fascinating and informative, as you might expect from an exhibition organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. (Fig 1) We also saw an exhibition at SFMOMA, about Amy Sherald, the artist who painted Michelle Obama’s official portrait. I found that portrait somber, but her other paintings are brimming with color and historical and cultural references. A mix of Alice Neel and David Hockney (Figs 2, 3) While we were at SFMOMA, we saw the last few minutes of Ragnar Kjartansson’s The Visitors which I first saw at the Louisiana Museum near Copenhagen. (Fig 4) SFMOMA purchased this incredible 60+ minute multi-screen piece with MoMA in New York. It’s in San Francisco until September 2025 and in NYC after that. Try to see it if you can.

Figure 1. Hallyu! The Korean Wave, Asian Art Museum

Figure 2. Amy Sherald’s riff on the famous G.I. & Girl Times Square kiss, look closely!

Figure 3. David Hockney one of series ’82 Portraits,’ 2018

Figure 4. The Visitors multi-screen video, Ragnar Kjartansson

One day, we met Nicolas and Min in Berkeley, toured the lab where she works (she’s a botanist working at UC Berkeley on a post-doc) and went to lunch. We ate one of my favorite dishes, Peking Duck. Why the name hasn’t been changed to Beijing Duck, I don’t know. I remember when you had to order Peking Duck at least 24 hours in advance. So I was delighted when this restaurant had it on the menu and everybody was happy to eat it. Delicious! Another day, Ginevra and I met Nicolas for lunch in San Francisco. He chose an SF institution, Tommy’s Joynt, it’s his kind of place. (Figs 5, 6)

Figure 5. Peking Duck accoutrements - scallions, plum sauce and pancakes

Figure 6. Tommy’s Joynt, San Francisco, check it out if you’ve never been

In other news, the house is finally painted, the painters are gone and so is the Porta Potty. Before the painters returned for their final day, Ginevra and I grabbed a hand saw and hacked down the tree in front of the house. We hadn’t planted it but we should have moved it to the garden before it got so big, but we just let it grow. It’s gone now. Well the trunk and thickest branches are still there. We’re currently deciding whether to paint it all pink or pink, orange and blue. My vote is just pink. (Figs 7, 8)

Figure 7. Me doing my part to chop down the tree in front of the house

Figure 8. Painter putting the finishing touches on the chimney - we are channeling Gaudi!

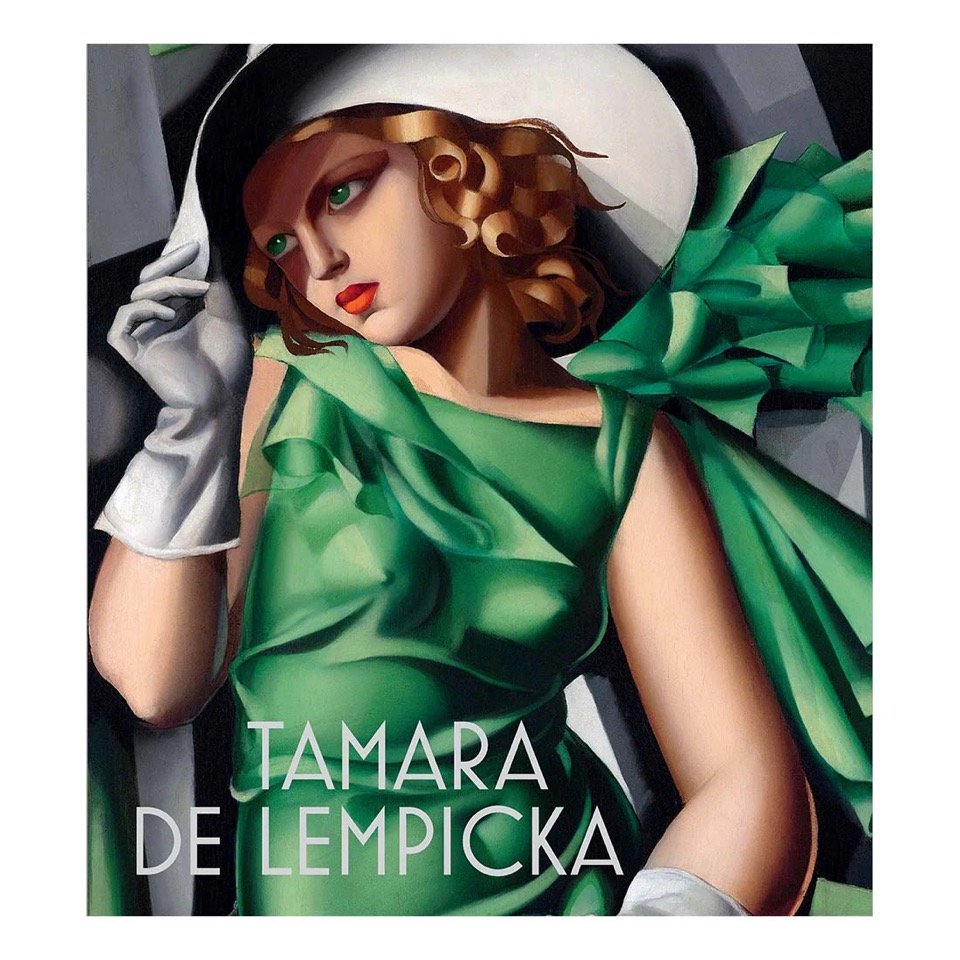

Today’s subject, two exhibitions now in San Francisco. At the Legion of Honor, San Francisco’s museum of European art, I saw an exhibition devoted to the American born artist, Mary Cassatt. At the de Young Museum, where the Rockefeller Collection makes it one of the country’s premier collections of American art, I saw an exhibition about an artist, born in Poland, who trained and worked in France and who later lived in the United States and Mexico, Tamara de Lempicka. (Fig 9)

Figure 9. Tamara de Lempicka Exhibition, De Young Museum

Typically, an exhibition about a European artist is held at the Legion and for an American artist, at the de Young. I have decided to interpret this scrambling as a positive sign, that American born artists who spend their entire careers in Europe can be considered European artists, at least for temporary exhibitions. If you want to see paintings by Cassatt at an art museum, you won’t find her with fellow French Impressionists but with American artists, only some of whom voyaged to Europe.

Both Cassatt and Lempicka have ben exhibited in Paris recently. In 2018, the Musée Jacquemart-André held an exhibition devoted to Mary Cassatt. In 2022, she figured in an exhibition on Impressionist Decorations at the Musée de l’Orangerie. Lempicka was one of the artists in a 2022 exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg, called Les Pionnières.

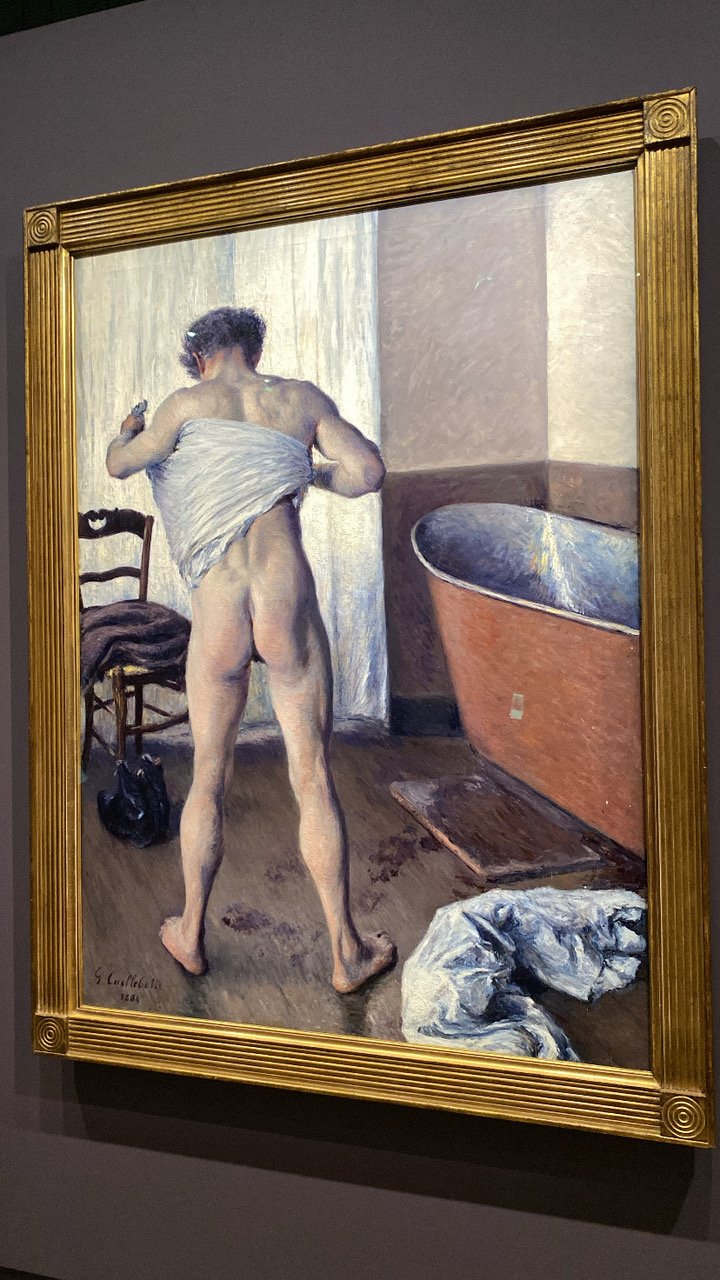

In one review of this Cassatt exhibition, the reviewer compared Cassatt’s portrayal of women’s work with Gustav Caillebotte’s portrayal of men at work. Tamara Lempicka’s Sapphic predispositions, which didn’t seem to bother anyone except her first husband, makes for another interesting comparison with Gustav Caillebotte, an exhibition of whose paintings I saw just before I left Paris called, ‘Painting Men.’ Caillebotte will be part of this discussion, too. (Fig. 10)

Figure 10. Man at his bath, Gustav Caillebotte, 1884

Let’s begin with Mary Cassatt. She was born near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1844, moved permanently to France when she was 22 and died there in 1926. (Fig 11)

Figure 11. Portrait of Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, 1880-84

According to the curators of this exhibition, Jennifer A. Thompson and Laurel Garber, Cassatt was ‘a committed member of the French Impressionist movement (with whom she began exhibiting in 1879) and a fiercely professional, aesthetically radical painter, pastelist, and printmaker.’

Cassatt was born into a wealthy family but financial security didn’t help her much. The constraints imposed upon her, by society and by her own family, made studying to be and then working as a professional artist, a constant battle. “As the youngest daughter in an upper-middle-class family, she was expected to marry… (W)hen it became apparent that she was intent on developing her artistic career, her father insisted that her studio pay for itself, a condition that spurred her to exhibit and sell her art…” Perhaps, but to me it seems more like a cruel attempt by a controlling father to break his talented daughter’s spirit. (Fig 12)

Figure 12. Mary Cassatt, self portrait, 1874

Restrictions on women of Cassatt’s class meant that the contemporary male world of the artist/flaneur was not open to her. Male Impressionists took as their subject, for their scenes of modern life, the world they knew, the places they frequented - like bars, brothels and boulevards.

Scholars have dismissed Cassatt’s paintings, contending that she simply painted what she saw. But that’s what her male counterparts did, too. Cassatt simply found her subjects in another world, the world of the upper-middle-class Parisienne. She depicted female relatives and friends in their private spheres, occupied with their customary activities - knitting, sewing, needlepointing, reading, preparing their toilette, caring for children, welcoming guests. Usually indoors, sometimes in gardens. Hettie Judah (The Art Newspaper) refutes the notion that Cassatt’s subjects were less modern, noting that the world Cassatt did have access to was, ‘the private feminine realm in which modern life of a different kind played out.’ (Figs 13-16)

Figure 13. Lydia Reading, Mary Cassatt

Figure 14. Lydia at her tapestry frame, Mary Cassatt

Figure 15. The Tea, Mary Cassatt

Figure 16. Reading Le Figaro (Cassatt’s mother), a newspaper mostly read by men of the period, Mary Cassatt

Cassatt occasionally took her subjects out of the house and into the theater. Her portraits of women outside their private spheres shows what it meant for such women to be in public and on display. Being in an audience should mean being the observer. One of my favorite paintings by Cassatt shows a woman looking through her binoculars, ignoring the man whose binoculars are trained on her. But we can’t ignore the fact that this woman is the object of the ‘male gaze.’ (Figs 17-19)

Figure 17. The Loge. A woman gazes through her binoculars at the scene in front of her, a man trains his binoculars on her, Mary Cassatt

Figure 18. Woman in the Loge, A young woman in decollete, with cheeks as flushed as her dress is pink, Mary Cassatt

Figure 19. Woman in a Loge, she’s covered up with her fan partially hiding her face, Mary Cassatt

Cassatt never married, never had children, but children frequent her canvases. She focused both on their ‘inner lives’ and ‘their intimacy with the women who cared for them.’ Her Little Girl in a Blue Armchair is so well loved because we can really see the toll that not moving has taken on this little girl. Fed up and bored, she slouches in her chair in a dress she doesn’t care about, would rather not be wearing. (Fig 20)

Figure 20. Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, Mary Cassatt

Her canvases of women with children neither minimize or trivialize the work “involved in cuddling, breastfeeding, bathing, dressing, educating, and cajoling young children…” In fact, the curators contend that Cassatt ‘made the physical and psychological work involved in childcare meaningfully visible for the first time in Western art.’ As Heddie Judah notes, and as every mother and caregiver knows, there is work in ‘making sure that a baby doesn’t die before its time.’ (Figs 21 - 23)

Figure 21. The Hug, Mary Cassatt

Figure 22. Nursing Mother, Mary Cassatt

Figure 23. Child’s Bath, Mary Cassatt

It is easy to assume that Cassatt’s images of women and children are images of mothers and children. That’s mostly not true. The babies and children are indeed those of family and friends. But the women ‘were generally domestic employees who worked for the artist or her friends.’ Cassatt, like her male counterparts, selected her models and paid them to pose. Sure she dressed them up in bourgeois attire, but she often left a ‘tell’ their work-reddened hands’ to remind us that ‘Cassatt's pictures (are not) an artless record of her own experience but, rather, an array of carefully crafted studio fictions.’ (Fig 24)

Figure 24. Detail of Child’s Bath, Mary Cassatt. Note reddened hand of working woman, not lady of leisure

In an interview, one of the curators stated that ‘under cover of acceptably "feminine" subject matter,’ her images of "women's work” ‘testifies to her own work’ Neither an amateur, nor a hobbyist, she was a professional artist who ‘smuggling(ed) a radical aesthetic program into her paintings of women and children.’

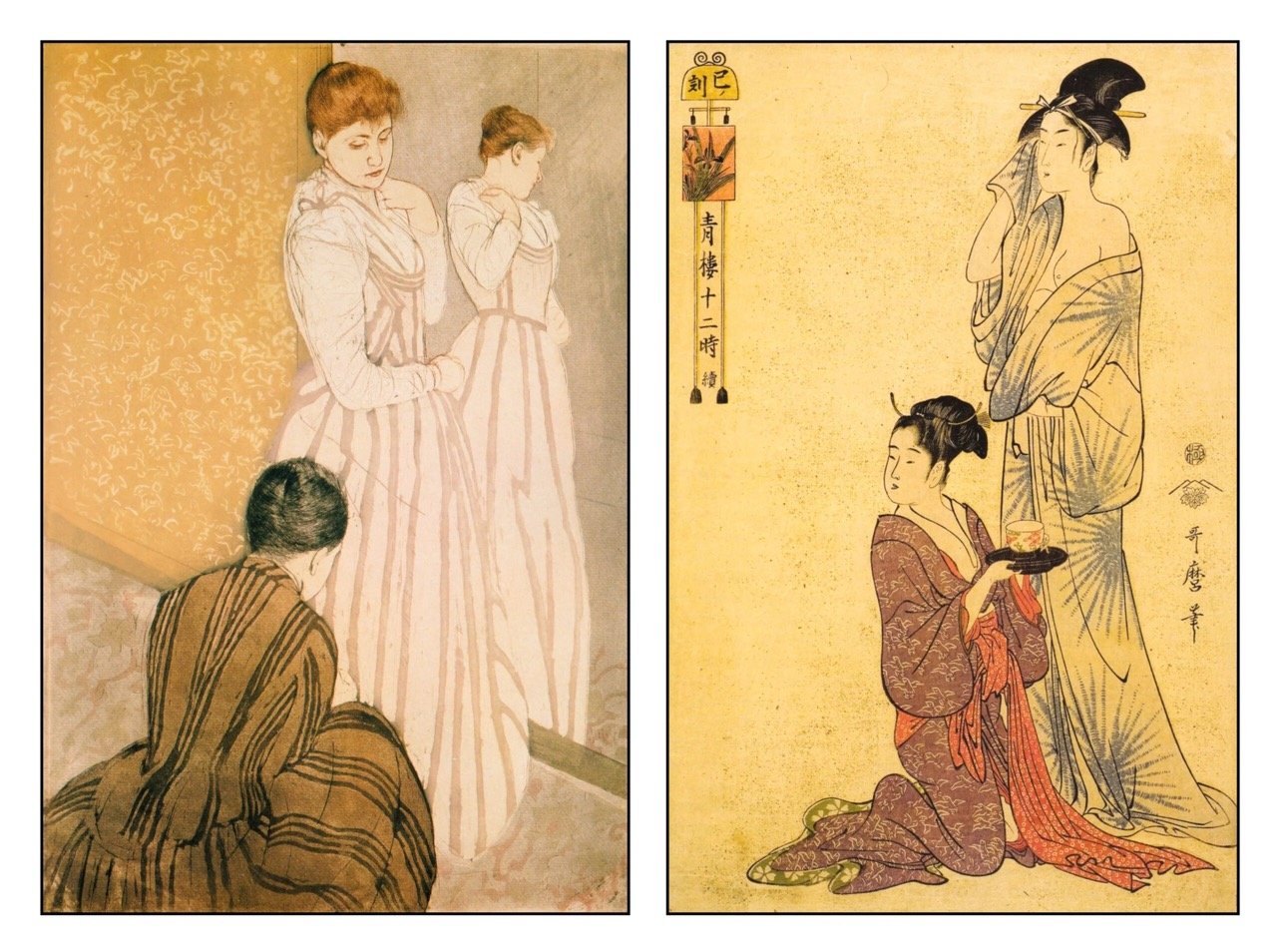

Cassatt was constantly experimenting with color and line. Her printmaking is a fine example. Inspired by an exhibition of Japanese woodblock prints that she saw at the École des Beaux Arts in 1890, she was inspired to try her hand at it. The ground breaking result was her “Set of Ten” color prints. As the wall text notes, Cassatt was “captivated by the bright colors, dynamic patterns, and everyday scenes in Japanese woodblock prints.” The next year, “she embarked on a series of color prints … which, like her canvases depict the bathing of a child, the drinking of tea, the sealing of a letter, etc. (Figs 25-27) She bought the equipment she needed so she could work in her studio. Cassatt invented a new method of printing in color, which the curators contend ‘are among the most inventive and technically daring works in the history of modern printmaking.’ Cassatt collaborated with a young printer, Modeste Leroy whom she credited in handwritten inscriptions below the images. Perhaps to acknowledge the labor involved in the project, perhaps in homage to the Japanese tradition of including both artist’s and printer’s signatures on a work. (Figs 28, 29)

Figure 25. Baby at Bath, Mary Cassatt, print

Figure 26. Cassatt’s Sealing Letter (1891)and inspiration, Utamaro’s portrait of geisha biting towel (1795) (photo credit: https://creatureandcreator.ca/?p=5119 )

Figure 27. The Fitting, Mary Cassatt (1891) compared to Utamaro’s Geisha with her Attendant, 1795 (photo credit: https://creatureandcreator.ca/?p=5119 )

Figure 28. The Bath, Mary Cassatt, 5th of 5 iterations

Figure 29. The Bath, Mary Cassatt. 2nd iteration (top right) 3rd iteration (bottom right) 5th iteration (left)

Cassatt shows her process in her paintings and pastels, too. Highly finished passages juxtaposed with areas in which both strokes of color and bare canvas are visible. With these paintings and pastels, Cassatt allows the viewer ‘to eavesdrop … as she applies patches of pastel and strokes of paint.’ (Figs 30, 31)

Figure 30. Sara in hat with dog, Mary Cassatt, pastel, note highly finished and less finished areas

Figure 31. The Long Gloves, Mary Cassatt, pastel

The curators pose a brilliant question: why is painting images of mothers and babies over and over again any different from painting water lilies (Monet) or painting apples (Cézanne) over and over again. The curators answer their own question, it’s because water lilies and apples ‘do not carry gendered meaning,’ and because of that, neither Monet or Cézanne have been ‘written off as sentimental.’

The curators also contend that taking the theme of "children and the work of caring for them" seriously, Cassatt confirmed the never ending tasks of childrearing and homemaking and her own own commitment to improving her technique, her craft.

Deborah Solomon, in her review of this exhibition, explained why Mary Cassatt never married and puts to rest the rumors about her and Degas. She didn’t fancy men. Solomon explain that in her 1911 will, Cassatt bequeathed some money and a painting to her longtime maid and companion, Maathilde Vallet. In a revision of her will, she increased the bequest to include all of her artwork (300 pieces) in her possession.

Solomon also wrote this,“…motherhood is work, lots of it. On the other hand, it’s hard to accept the premise that Cassatt’s paintings take as their subject the aches and infelicities of unpaid labor.…The idea of her as a champion of work seems especially strained when one recalls such genuine Impressionist odes to labor as Degas’s bone-weary laundresses ironing sheets, or Gustave Caillebotte’s “Floor Scrapers,” with its three hunched workers renovating an upscale apartment.” (Figs 32, 33)

Figure 32. Les Repasseuses (laundress, ironers) Edgar Degas

Figure 33. Les Raboteurs (Floor Scrapers), Gustave Caillebotte

There are a couple things to unpack here. Firstly, the women in Cassatt’s paintings of women and children were not unpaid mothers but paid models. The women who minded children in Cassatt’s milieu were mostly hired domestic help whose work was every bit as tedious and often as backbreaking as the work of laundresses. And for both the laundresses and floor scrapers, the work day did eventually end. With a baby or a small child, anyone who has ever been a mother or a minder knows that’s not the case. And I’m guessing that the next stage in the lives of many of Degas’ repasseuses (ironers) was unpaid work as mothers. (Fig. 34)

Figure 34. The Family, Mary Cassatt and how she found contentment

Solomon also claimed that Cassatt belongs to the second tier of Impressionists,” who “cannot be said to inhabit the same exalted plane as Degas or Manet.” I agree with Carlos Valladares (Art in America) who wrote in response to that claim: “This ranking business! It’s loathsome, tiresome. Arrêt!

Oh dear, I’ve run out of space, Lempicka and Caillebotte next week! Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Thanks to everyone who commented on our house painting journey. Color is a very personal thing, not everyone has the same taste (thank goodness!!)

New comment on In Vivid Living Color:

Wow, what a journey in color and creativity! Thank you for sharing so much of your, and your whole family's, personal process along this path of exploration. Looking forward to seeing the photos when the exterior is completed. Though, in reading this article, I realize that it is probably never really complete There are probably always new ideas on the way. Seems like you must have an amazing time when you are together, collaborating and creating - Enjoy, Sydney, Portland, Oregon

I love this post about your home! And the elements all three of you have contributed to making it your home also show your joy. The pink, orange, white , and blue all work so well together and remind me of a dress I found with those colors in Hawaii when I was 19 years old. That was decades ago but it’s still fresh in my mind. Thank you for taking us on your journey of color and joy. Happy new year. Elaine

Brilliant: “Unless you know what you are looking for, you don’t know what you are looking at”. Kathryn, Washington, D.C.

Dr. B. As to the house colors I am not sure if I would have chosen those colors. The apartment building across the way had an almost purple, cack and repair hiding undercoat applied..yikes..before the final marine blue went over it; the trim is white so this worked. Some are still feeling it is purple. This building had been neglected for many years until a new owner from Southeast Asia purchased it and began the long task of improvements. Color is very subjective and varies depending on the light and the time of day in my opinion. Thank you, Dianne

I enjoyed your walk on the wild side! It makes me realise how far from the edge I live. Suzanne

BTW, after looking again and again on the talents of Ginevra my mind clicked over to the thought…..‘regrettably she could have been one of the top scenic designer in 1940s/1950s Hollywood films with all those magnificent Technicolor films.’. On most of the MGM films the credits list Cedric Gibbons but with all those films he had to have had a staff of talented & creative folks like your daughter. BTW2, on that last photo of Ginevra from the newspaper article only confirmed my idea that she should be doing some high-end $$$$$ modeling for Vogue and others. Bill, Ohio

Beverly, you post often and at length most times. I can think of some pertinent questions: * How do you DO it? * How much of the work is actually done by Ginevra? * Could she fill in for you 100% if the need arose? * Where do you find the time? * Where does Ginevra find the time? * How do you find the strength of mind and body to keep at it? * Am I the only one of your subscribers who feels overly challenged by the limitations of his or her own lack of time and waning of mind and body staminas? <rueful smile> Morris, N Carolina

I adored Burano. So colorful in bright shades! Mille Grazie, Dr. B SA