Where’s de Waal(do)?

Edmund de Waal at the Musée Nissim de Camondo

I have written about the Musée Nissim de Camondo, the collection and the collector here: Musee Nissim de Camondo. Today I am going to talk about the temporary exhibition currently at the museum, on through next May created by Edmund de Waal. The Camondos were a wealthy family, peripatetic by circumstance, not by choice. They were expelled from Spain in 1492 with all the other non-Catholics who refused to convert. Next port of call was Venice where they prospered until Austria invaded and they were exiled. Again. Then to Istanbul, and despite sumptuary laws aimed at non-Muslims, their wealth grew. Until it was time to leave there, too. In the 1860s, the family ended up in Paris. Which is where this story begins.

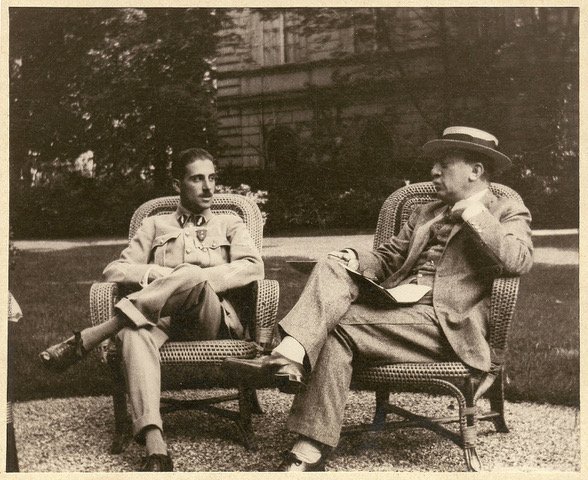

I thought about my thoughts about this family and this museum as I read an interview with Edmund de Waal in The Times of Israel. Edmund de Waal is a ceramicist living in London and the author most recently of Letters to Camondo. Letters to his uncle, Moise da Camondo. (Figure 1) In it, he asks his uncle, the collector who purchased exquisite French 18th century furniture, decorative arts and paintings, all with impeccable pedigrees (provenance), the same two questions I raised in my review of the museum. Did Monsieur de Camondo really think that by being more French than the French, by collecting the best 18th century French art that money could buy, that he would be accepted as French? Did he really think that in a country of very old money and very entrenched anti-semitism, anyone would forget that his was a family of successful bankers and Sephardic Jews.

Figure 1. Photograph of Nissim de Camondo (left) with father Moise de Camondo

De Waal spoke about the complex emotions he felt writing the book. He called it a “sort of frustration or anger with the past… You endlessly go back into history and ask why didn’t you see this coming? Why didn’t you do this? How could you possibly have done that?” Indeed. All the Jewish optimists are dead.

And de Waal spoke about his exhibition at the Nissim de Camondo Museum in conjunction with the book. De Waal is related to de Camondo through the Ephrussis, another Jewish family of diaspora bankers. Their story began in Odessa where they attained great wealth and from which they were forced to flee. They wound up in Vienna, abandoning grain selling for banking along the way. While still in Vienna they opened branches of their bank in London, Paris and Athens. Both families share the same trajectory. Both fled from country to country, hounded by one Jew hating regime after another. Until they were finally mostly annihilated thanks to German efficiency and European complicity.

The Ephrussis are now virtually forgotten. Except maybe for the Villa Ephrussi-Rothschild in Cap Ferrat and Edmund de Waal’s 2010 book Hare with the Amber Eyes. And maybe also for Charles Ephrussi, (Figure 2) who, like most members of his family, was an intellectual and art collector. He was also a model for the character of Charles Swann in Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time. Proust was a member of the clan, too. His mother was Jewish.

Figure 2. Portrait of Charles Ephrussi

In Paris the Ephrussis and the de Camondo family lived on the same street, near the Parc Monceau. (Figure 3) An elegant part of the city now, an enclave of the nouveau riche and their enormous, ostentatious houses, then. Émile Zola described these houses and those people in his 1871 novel, La Curée. Each mansion, he wrote, was “an opulent bastard of every style”. McMansions anyone?

Figure 3. Parc Monceau

When Moise’s son Nissim, a pilot during the first Great War died in a plane crash, Moise just stopped - working, entertaining, living. His house became a memorial to his son, a mausoleum. He gave the house, and all of its exquisite contents, to Les Arts Decoratifs (the precursor of MAD with which it is still affiliated). The stipulation, as per Moise de Camondo’s will, “Don’t lend things. Keep the blinds down, keep the dust away, don’t add objects to these collections.” And for the past 85 years, nothing has changed. It is the kind of museum, that unless you are passionate about French 18th century furniture and decorative arts, you go infrequently. This is a place of remembrance and sadness. It is a heavy place.

So, how did Edmund de Waal come to mount an exhibition at the Musée Nissim de Camondo? Simple. Somebody at the museum asked him. But as he began to think about what he would do, the pandemic happened and he couldn’t get to France. So he wrote his book instead.

Now finally, the museum is open and the exhibition is here. De Waal told The Times of Israel that as he thought about how to proceed, he thought about the words of the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, author of the Arcades Project (about 19th century Paris) (Figure 4) who committed suicide in 1940, in Spain, when his attempt to flee the Nazis seemed thwarted. Benjamin wrote, “The most deeply hidden motive of the person who collects can be described this way: He takes up the struggle against dispersion.”

Figure 4. Passage Walter Benjamin, 4ieme arrondissement, Paris

De Waal further explained. “What [Camondo] was trying to do was a classic thing of Jewish collectors, which is a sort of bulwark against diaspora, and against traveling and movement. … It was Moïse saying, we are now Parisian and this is where we are, and I am going to keep this all together to represent that.”

We all know how that story ended. And we all know that stuff cannot keep us safe. In fact, we would all be better off getting “Mary Kondo/ed’ and deaccessioning as many of our possessions as possible so that if we ever find ourselves in a comparable situation, our stuff won’t paralyze us, keep us from moving on, seeking safety, getting out of Dodge.

I was looking forward to this exhibition both because it is in a space that has never welcomed a temporary exhibition before and also, more generally, because I am particularly fond of temporary exhibitions. I especially appreciate the ones that enter into dialogue with a museum’s permanent collection or with a particular site. Among my favorites are the ones that are presented annually at the Chateau of Versailles. A contemporary artist is invited to present work in the Chateau and on its grounds. This year’s temporary exhibition by François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne in and around the Petit Trianon was especially successful. I wrote about it here: Whimsical World of Les Lalanne. (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Les Lalanne at the Petit Trianon, Versailles, Summer 2021

When my kids and I were in Athens a couple years ago a sculptor had taken over the ground floor and gardens of the British Center there. In a city overflowing with marble fragments from a storied past, this artist fashions garbage bags and other disposable items from our world into marble. Trompe l’oeil and contemporary statement all in one. (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Andreas Lolis, British Center, Athens, Fall 2018

In Paris, temporary exhibitions often conclude with contemporary riffs on the subject at hand. An exhibition about the Bauhaus at MAD one year ended with examples of the Bauhaus’s influence on contemporary artists. In the last room of the kimono exhibition at the Musée Guimet were examples of the influence of kimonos in Western fashion and contemporary Japanese design.

But none of these experiences prepared me for de Waal’s exhibition. His exhibition is in another category altogether. First, let me tell you what happened when my friend Sharon and I went to the museum a few weeks ago. We hadn’t seen each other since early summer and I was looking forward to hearing about her final three weeks of walking the Chemin de St. Jacques. After the exhibition, of course. It was my idea to go to this museum. And since she hadn’t been there in years, she agreed.

When we reserved our tickets, the description about de Waal’s exhibition that is on the website now was not on the website then. So we didn’t know that the boxes in the courtyard were part of the exhibition. They didn’t bother Sharon. They bothered me. I knew about Moise de Camondo’s will. When we walked into the vestibule, there was a large scruffy table and a heavy red velvet chair nearly identical to one my daughter bought at our favorite brocante in Issigeac. (Figure 7) I asked a young guard if the table and chair were part of the exhibition. He didn’t know what I was talking about. With his blank stare, I wasn’t sure I knew what I was talking about either.

Figure 7. De Waal exhibition, Musée Nissim de Camondo, Paris, 2021-2022, and my chair! (right)

At the ticket desk, we took a pamphlet, ‘Edmund de Waal au Musée Nissim de Camondo, Lettres à Camondo’. Sharon suggested we tour the museum and discover de Waal’s pieces as we wandered. Sounded like a good idea. Half way through the house, we changed our plan since we hadn’t seen anything we could confidently say was part of an exhibition. We retraced our steps. The pamphlet had a map on one side and a written description on the other, but we still felt lost because there were no images. We knew approximately where things were but we had no idea what anything looked like. Now the website includes photos of de Waal’s pieces.

Here is some of de Waal's explanation from the leaflet, “I make small groups out of porcelain and oak and gold. I shuffle these porcelain fragments. I stack them onto the desks where Moïse wrote to friends and dealers, the desks of the chef and the butler where they wrote their lists…” Poetic, yes. But where/what was he talking about.

Again de Waal, “I decide that Moïse needs another desk. … My desk is in the form of a letter, words written into porcelain brushed over gold leaf. I write: I find this difficult.” Aha, here is an explanation for the large scruffy desk in the vestibule.

De Waal tells us that he “..put some shards into a drawer of the Sèvres table… (and) some piles of porcelain notes into the Library and a few bowls into the Porcelain Room to keep Buffon’s beautiful birds company.” We noticed those notes in the Porcelain Room. We thought they were paper. But they are porcelain. (Figure 8)

Figure 8. De Waal Bowl with porcelain notes in it, Musée Nissim de Camondo, Paris

De Waal also explains that he created objects he didn’t intend people to see, placed inside closed cupboards and drawers. “They are just there and hidden. So I am sort of making another element of the archive and putting them away”. This is becoming a museum of the mind. Objects created to be not seen.

We had noticed but not known what to make of the black frames we saw in the pantry. De Waal’s explanation is this, “… I make five black vitrines and put lead and shards in them… These are stele for the family, for Nissim, Béatrice, Léon, Fanny and Bertrand. They are i.m., in memoriam.” (Figure 9)

Figure 9. De Waal Vitrine at Musée Nissim de Camondo

This is a temporary exhibition in dialogue with the people who lived in this house, not the art collected by the patriarch of the family. I am confused, the house is already a memorial, a mausoleum. These five stele honor one man who died for his country and a family of four who died at the hands of their country. Same country.

De Waal explained the boxes in the courtyard (which I had thought were wood) this way, “I put eight stone benches in the courtyard, places to sit and pause by yourself or with others. …They are polished smooth so that they feel worn away…. They are my form of kintsugi, the manner in which some broken porcelain in China and Japan are repaired with lacquer and gold, a way of marking loss.”

These are the boxes I saw when we arrived. (Figure 10) To me they looked like coffins for the murdered Camondo family or maybe the railroad cars in which they rode to their deaths at Auschwitz. Before you go into this house of sadness, you don’t need these benches for quiet contemplation. After you have seen the film that concludes with the murder of Beatrice and her family, you want to escape the sadness, and maybe not contemplate it.

Figure 10. De Waal Stone Benches in courtyard, Musée Nissim dė Camondo

I don’t know what to say. And that is unusual for me. I had just read that de Waal will be co-curating an exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York this month. And I wanted to know more about him and the exhibitions he has already curated. I learn that his focus is on memory and exile. That as a ceramicist he works with porcelain, gold, marble and bronze. That his display cases are always minimalist.

But surely the other temporary exhibitions have not concentrated on the collectors and forsaken the collections. I continued my research. The first temporary exhibition de Waal was commissioned to create in the U.S. was at the Schindler House in Los Angeles. His exhibition responded both to the house and to its owner, Rudolf Schindler. Specifically the idea of exile. Of leaving one place for another. As Schindler had done when he left Vienna and moved to Los Angeles in the 1920s. (Figure 11)

Figure 11. Edmund de Waal, exhibition Schindler House, Los Angeles

De Waal also created a temporary exhibition at the Frick Collection in New York, another mansion museum. He was the first contemporary artist to mount an exhibition in that space. De Waal created a series of sculptures in response to particular objects in the collection. Displayed alongside them. (Figure 12) But he did get a dig or two in at Frick. Some of his pieces are made of steel, a reference to how Frick amassed his fortune, which he used to buy an art collection to rival, maybe surpass those in Europe.

Figure 12. De Waal exhibition, Frick Museum

The exhibition scheduled for the Jewish Museum is going to be different again. It will take as its subject de Waal and his book The Hare with the Amber Eyes. The museum will become a domestic setting according to Ms Diller whose firm Diller Scofido + Renfro is doing the exhibition design. The focus will be on the Japanese netsuke that de Waal inherited from his uncle in 1997. (Figure 13) The museum will include many of the same pieces - art, objects, furniture - that de Waal talks about in the book. This will be an exhibition of a collection and its collectors, concluding with the current collector, the author of the book. And de Waal has read passages from his book for the accompanying audio guide. If you are going to be in New York anytime in the next 6 months, you should definitely check it out. The exhibition in Paris is very subtle. You have to work to see it, think a lot about it to appreciate it. I’m glad I went and I’m glad I learned more about the artist to share with you.

Figure 13. Upcoming exhibition on Edmund de Waal’s book, The Hare with the Amber Eyes, Jewish Museum of New York.

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you