Use your words

Barbara Kruger at the 59th Venice Biennale

Me immersed in Barbara Kruger install at the Biennale

This week I was going to talk about two artists whose work I saw in Venice, at the Biennale. Both of whom I have been about a lot since then. But, as it turns out, each deserves a separate post. So, it will be Barbara Kruger today and Simone Leigh next week. (Figures 1 & 2). They are both enjoying a moment at the moment and it’s likely that you will have seen or will soon be seeing the work of one or the other or maybe even both, at a museum or gallery near you!

Figure 1. Barbara Kruger, Arsenale, Venice Biennale, 2022

Figure 1a. Barbara Kruger, Arsenale, Venice Biennale, 2022 (with unknown child interloper).

Figure 2. Simone Leigh, Arsenale, Venice Biennale, 2022

When I taught the undergraduate Introduction to Art History, modern art was the art with which I had the least affinity. Because I like stories - biblical, classical, historical - doesn’t matter. And I like art that I can show has a link to art of the past. And I like words. And artists who take a stand, who make a statement. And most of these passions of mine are absent in modern art’s major movement - abstraction.

Then I developed a course I called Women as Artists / Women as Art. Putting the course together, I discovered the work of three contemporary female artists. Whose work was my entree into modern and contemporary art. The women are Cindy Sherman, (Figure 3) whose retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton I wrote about a year or so ago. She mines art history and advertising to create mostly self portraits that make us question our own ideas and assumptions. Jenny Holzer, (Figure 4) whose ‘text art,’ is all words - mostly short phrases in big letters on public buildings that cannot be ignored, cannot be ‘unseen’. Holzer's work calls out violence and oppression, supports sexuality and feminism. The third artist is Barbara Kruger, who, like Sherman, culled images from advertising. And for whom, like Jenny Holzer, text is essential. She manipulates sequences of words to show how they define and confine us.

Figure 3. Cindy Sherman, Venice Biennale, 2011

Figure 4. Jenny Holzer, Protect Me From What I Want

Sherman, Holzer and Kruger are all feminists, all postmodernists (that is, they believe in the “role of ideology in asserting and maintaining political and economic power.”) In their art, they use the techniques of mass communication and advertising to explore issues and isms from gender and identity to feminism and consumerism.

Kruger is experiencing a ‘moment’ at the moment. There was the enormous Biennale installation that I saw and nearly simultaneously, retrospectives in Los Angeles at LacMA, in Chicago at the Art Institute and in New York at MoMA and David Zwirner Gallery. Not bad for an artist who is a few days short of her 78th birthday (Jan 26).

When she was 21, and after one semester at Parson’s School of Design, Kruger got a job at Condé Nast Publications as a graphic designer, working first for Mademoiselle and then for House and Garden Magazine. For a decade, she immersing herself in images and fonts. As Barbara Feinstein (Guardian, 2022) notes, Kruger’s decade at Condé Nast “taught her the power of words and pictures and the immediacy of a visual elevator pitch (which she used) as an image-based call to action”.

When she began to do art, she gravitated toward those experiences. She paired found photographs from mainstream magazines with assertive, challenging phrases. Examples of her instantly recognizable slogans include "I shop therefore I am,” written on a credit card shape, held by a female hand. (Figure 5)

Figure 5. I shop therefore I am, Barbara Kruger

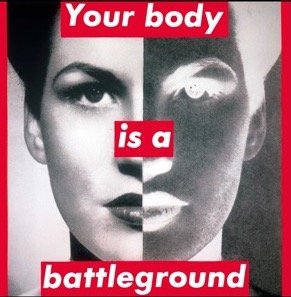

"Your body is a battleground,” (Figure 6) written across a woman’s face began as a poster she designed for the 1989 Women’s March on Washington, in support of women’s reproductive rights. She offered it to NARAL but they already had a poster. So she made copies on her own and plastered them all over town herself. After the march, she deleted the details of the march from the poster. From poster to art to icon. Which she brought out again last year after the Supreme Court ruling that undid 50 years of law. (Figure 7) The woman’s face is the same but the message has been updated.

Figure 6. Your body is a battleground, Barbara Kruger after 1989

Figure 7. Who Becomes a “Murderer” in Post-Roe America? Barbara Kruger

Kruger’s methods and materials have changed with the times, transitioning from small posters glued to walls to enormous digital screens on her own vinyl walls. With changing words accompanied by sound, bringing new and nuanced meaning to a text, sometimes her own, sometimes riffs on, sometimes the exact words of, others. As her way of presenting her ideas has changed with modern technologies, her words can change, her ideas can develop as part of the work itself.

Roberta Smith, art critic for the NY Times, writes that while some have faulted Kruger “for being visually repetitive, haranguing (and) propagandistic,” Smith refutes those labels because, Kruger’s “forceful voice is also restrained and witty.”

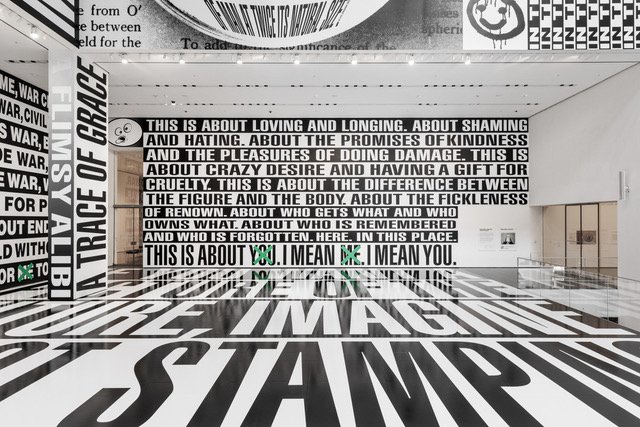

The installation at MoMA, “This is about You. I Mean Me. I Mean You” recalls the text Kruger put across Kim Kardashian’s naked body for the cover of W Magazine, “It’s all about me, I mean you, I mean me.” (Figures 8, 9) That white text on red scroll has morphed into black text on white ground punctuated with green crosses playing with pronouns.

Figure 8. This is about you I mean me I mean you (center bottom) Barbara Kruger

Figure 9. It’s all about me I mean you I mean me

Smith encourages museum goers to move slowly through the show, to “absorb the words, grasp their meanings.” Like this sequence - “War time, war crime, war game” which eventually evolves into “War for a world without women.” Or this one: “This is about loving and longing. About shaming and hating. About who is remembered and who is forgotten. Here. In this place.” When the visitor looks down, they are stepping on George Orwell’s prophetic words: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face, forever.” (floor of Figure 8)

Here is a not so fun fact. Supreme, the skateboard and apparel brand established in 1994, took their logo—the white word "Supreme" on a red box—from Kruger's signature style. (Figure 10) Which the founder of Supreme readily admitted when asked. Kruger, who had never copyrighted this configuration, didn’t say anything. That is until 2013 when Supreme sued another clothing company for using the Supreme logo on their t-shirts and tops, "Supreme Bitch”. (Figure 11) When asked to comment, Kruger said this, "What a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers. I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce. I'm waiting for all of them to sue me for copyright infringement."

Figure 10. Supreme Logo

Figure 11. Supreme Bitch by MTTM

As Thora Siemsen, (Frieze) recounts, four years later, in conjunction with Performa 17, Kruger let everyone know exactly what she thought of Supreme and their uncool antics. She created a performance piece, “Untitled” (The Drop.) (Figure 12) It’s a term that was initially associated with Nikes and record albums. Now it's a term that everyone uses to announce the release of anything new. Like Supreme announcing that a new line of clothing is going to ‘drop’ ie, become available in stores. Kruger mockingly replicated the frenzied reaction of Supreme consumers to the news of a ‘Drop’. Kruger performed her piece in a former retail space. She hired security guards to manage the crowds (like Supreme does). Inside, performance participants sold beanies, hats and skateboards, with text, like: “Want it buy it forget it” and “Whose hopes? Whose fears? Whose values? Whose justice?” (Figure 13) Kruger also riffed on Supreme’s MetroCard collaboration. Supreme’s card simply had their logo on it. Kruger’s MetroCard had questions on it, like ‘Who is healed? Who is housed? Who is silent? Who speaks?.’ (Figure 14) Crucial questions about contemporary life.

Figure 12. “Untitled” (The Drop) Barbara Kruger, Performa 17, New York

Figure 13. Merchandise sold at Barbara Kruger’s performance piece, “Untitled” (The Drop)

Figure 14. MetroCards, Barbara Kruger

On a more positive note, Kruger collaborated with choreographer Benjamin Millepied for a dance he created in 2013 called ‘Reflections’. Kruger designed the stage set and costumes. Written in white letters on a red background, were the words Stay and Go. On the floor, “thinking of me thinking of you” (Figure 15) As one commentator noted, in ‘Reflections,’ men and women dance in “complex, adult encounters. There is no central male-female pas de deux…Life…is more complicated and interesting than that.” Exactly what Kruger’s art aims for.

Figure 15. “Reflections” choreography, Benjamin Millipied, Stage set & Costumes, Barbara Kruger

Figure 16. Barbara Kruger, Venice Biennale, 2005

The Venice Biennale of 2022 was not the first in which Kruger participated. In 2005, she installed a digitally printed vinyl mural across the entire facade of the Italian pavilion. Green on the left, white in the middle, red on the right. Columns on which the words “money” and “power” were written in English and Italian. (Figure 16) And on a wall, "Pretend things are going as planned” and "God is on my side; he told me so.”

Figure 17. Pledge of Allegiance, Barbara Kruger, 2008

In 2022, Kruger was back with her now standard vinyl murals. Words are everywhere but no words command more attention than the reprise of Kruger’s 2020 Pledge of Allegiance which was itself a video version of her 1988 work “Untitled” (Pledge). (Figures 17, 18) To the sound of letters being struck one at a time on a manual typewriter, or more likely, the ping ping of Wall Street ticker tape, the words of the Pledge appear and then change and then change again. As Christopher Knight writes in the LA Times, “(r)ather than X-out and replace words,…like an editor with a blue pencil crossing out a text until the right word is found,” she digitized it. In the first phrase of ‘I pledge allegiance,’ the word ‘allegiance’ becomes ‘adherence’ then ‘adoration’ then ‘anxiety’ then ‘affluenza’ before becoming ‘allegiance’ again. And then it is the next phrase’s turn. The process continues phrase by phrase as words that have nothing to do with the Pledge as you know it, replace and then are replaced by other words. Sometimes the phrases make sense and sometimes they don’t. Finally it dawns on you that our present reality, our own history is being edited and rewritten, dictated and desecrated, by persons or persons not under our control.

Figure 18. Pledge of Allegiance, Barbara Kruger, Venice Biennale, 2022

Kruger also takes on the standard text of a will, “I, being of sound mind and body,” and the text of a marriage vow, “I take you, to have and to hold.” Both go through the same series of iterations and degradations before morphing back into the phrases as we know them. And all around are phrases like these, “In the Middle there was Confusion,’ (see above Figure 18) and ‘Your Voice, Your Fate, Please Adore, Please Mourn.’ (Figure 19) Some in Italian as well as English. Click here and take a look: Your Voice Your Fate.

Figure 19. Your Voice, Your Fate, Please Adore, Please Mourn

Kruger said this about the biennale and all the retrospectives she is having now: “I’m so appreciative of the current visibility of my work and so welcome it as I approach my centennial.”

Simone Leigh next week. In the meantime, here are some Kruger Quotes:

“My work has always been about power and control and bodies and money.…”

“My image/text works attempt to show and tell the stories of bodies and minds. How they might be pictured and how they picture themselves”

“My work is, at times, detonated by taking another breath, by the repetitions of the everyday and how that everyday is constructed by both the brutal hierarchies and punishments of global events and the more localized tenderness and kindnesses that are either offered or denied.…”

“My work is seldom incident- or event - specific but tries to create a commentary about the ways that cultures construct and contain us”

“My work has consistently focused on the vulnerability of bodies. Of how power is threaded through cultures. On how the choreographies of hierarchies and capital determine who lives and who dies, who is kissed and who is slapped, who is praised and who is punished”

“Pictures and words seem to become the rallying points for certain assumptions. There are assumptions of truth and falsity and I guess the narratives of falsity are called fictions. I replicate certain words and watch them stray from or coincide with the notions of fact and fiction”

“In this time of massive collisions of voyeurism and narcissism and quickened (I think she means shortened) attention spans, I feel very engaged with the self-presentation and direct address social media offers. How millions of us are pleasured, desired, worshiped and shamed by these picturings.”