Trash or Treasure?

Subodh Gupta at Bon Marché

Today we’re off to Le Bon Marché, not for the soldes (sales) which I mostly try to avoid because even if Marie Kondo has renounced her war on clutter, I haven’t. My one bedroom flat in Paris won’t let me. It’s not stuff we’re here for, it’s Le Bon Marché eighth annual January Carte Blanche solo exhibition. The artist who has been selected this year to create thought provoking and site specific work is Subodh Gupta. Gupta was selected by whomever makes those decisions for LVMH, the company that owns Le Bon Marché and is owned by Bernard Arnault, the richest man in the world. What he purchased most recently was a painting for the Musée d’Orsay, which that museum couldn’t afford (Gustave Caillebotte’s ‘A Painting Party,’) rather than overpaying for a company he didn’t need. And that’s how Arnault went from #2 to #1 richest guy in the world. Decisions, decisions!!

I first saw Subodh Gupta’s work a couple of years ago at the GalleriaContinua. Not their outpost in the Marais that opened just before the pandemic shut everything down, but GalleriaContinua’s gallery in the suburbs of Paris, in Les Moulins, (1 hour by car, 90 minutes by public transport). GalleriaContinua’s exhibition spaces at Les Moulins are industrial in scale. When I was there, Subodh Gupta had a huge presence. One of his works grew like stalagmites from the cement floor and fell like stalactites from the unfinished ceiling. (Figure 1) The piece was a maze. Like architecture, it defined the visitor’s progression through it. The colossal hanging and soaring piece was made of hundreds of stainless steel and aluminum objects, his signature material. There’s another Gupta exhibition at GalleriaContinua on now through mid-May, called ‘My Village’. It includes paintings, oversized objects and free standing sculptures. (Figures 2, 3) If you have a chance to see Gupta’s exhibition at Le Bon Marché (and even if you don’t, it comes down February 19) and you love it as much as I do, then you’ll want to make your way to Les Moulins to see Gupta’s work there, too.

Figure 1. My Village, Subodh Gupta, GalleriaContinua, 2022-23

Figure 2. My Village, Subodh Gupta, GalleriaContinua, 2022-23

Figure 3. My Village, Subodh Gupta, GalleriaContinua, 2022-23

Here is how I described Gupta’s installation at Les Moulins last September. “Made of many small tin and stainless steel objects, useful objects, functional objects, all related in some way to food. Some of which are familiar to everybody - like colanders and pots and tea kettles. Some of which speak to Gupta’s native country - like tiffins, those multi-layered containers in which travelers in India pack and eat their food. Tools for cooking and preserving food, containers for offering and eating food.” All of which, according to the gallery sheet, “constitute a central and recurrent motif in Indian life, both religious and cultural, from its earliest times up until today.” What I wrote was accurate, but in describing the ‘what’ I didn’t tell you about the who and didn’t say enough about the why. So, now let’s explore those questions - who is Subodh Gupta and why he is so dedicated, indeed fascinated with the tools and utensils of everyday life in India.

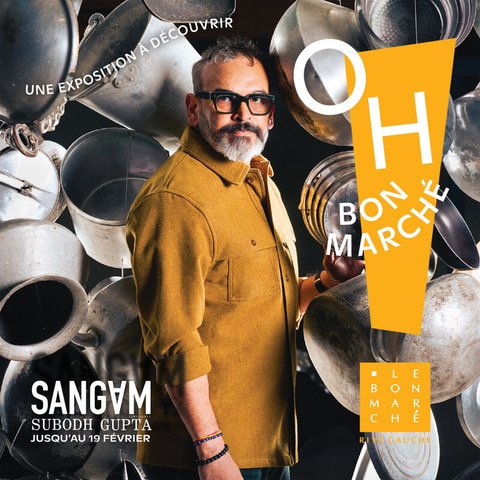

Gupta, (Figure 4) who is 59, was born in a small town in Bihar, India, the poorest part of India. I read that to call someone a Bihari is to call that person uncouth and uncivilized, as well as poor. When his father died in his early 40s, Gupta, 12 at the time, was sent to live with his mother’s family in a remote village. What Gupta remembers from that period is this: "Not a single school kid wore shoes, and there was no road to go to school. Sometimes we stopped in the field and we sat down and ate green chickpeas before we went to school.”

Figure 4. Sangam at Le Bon Marché, Subodh Gupta, 2023

Art school sounds like more of the same. “Can you imagine,” he wrote, “the library of an art college forever locked? I just felt so lost when I passed out of the college. Had there been proper infrastructure in the college, I feel I wouldn’t have had to experience the same kind of struggle.”

Gupta initially worked with a theatre group and then experimented with film and performance art, sculpture and painting. For the past 25 years, he has been making art fashioned from ubiquitous objects of everyday life in India. (Figures 5, 5a) These objects are both what he works with and what his work is about: cultural identity. For Westerners, these objects represent an exotic, foreign culture. For Indians, these objects are everyday ones used by nearly everybody. The way he uses them in his work changes our relationship with them. The scale of his work and the sheer number of objects he uses transforms them. They are no longer humble, they can no longer be ignored.

Figure 5. Utensils and cord, GalleriaContinua, Subodh Gupta, 2022

Figure 5a. Hanging Teapot, GalleriaContinua, Subodh Gupta, 2022

Steel tiffin boxes (Figure 6) are used daily by millions of Indians. In the past, Gupta used mass produced, brand new ones. He has also crafted these utilitarian objects from shiny metals and polished wood. In recent years, Gupta has abandoned new objects for abandoned ones. Battered and bent, these discarded items bear witness to the lives they touched along their way to the trash heap. Gupta rescues them so that he can celebrate their scratches and scars; their nicks and dents. Transformed into soaring sculptures, they achieve a prominence and dignity, even if their distressed state is a constant reminder of their original purpose.

Figure 6. Indian Tiffin Box available for purchase on Amazon

Through these objects, viewers can detect what anthropologist Bhrigupati Singh describes as ‘the patterns we create through our diurnal scrapings, the marks we leave night and day, through rise and fall, joy and sorrow, on the surfaces of our ordinary domestic vessels that journey with us, sometimes for years. What we discover in the process are intricately crafted pieces of the cosmos.”

Gupta has said this about the objects (tiffin boxes, thali plates, colanders, tea pots, milk pails and even bicycles) that have become the centerpieces of his work.

"All these things were part of the way I grew up. They were used in the rituals and ceremonies that were part of my childhood. Indians either remember them from their youth, or they want to remember them.”

On the symbolism of ritual elements of Hindu life in his work, Gupta says "I am the idol thief. I steal from the drama of Hindu life. And from the kitchen - these pots, they are like stolen gods, smuggled out of the country. Hindu kitchens are as important as prayer rooms.”

And also this, “I was born into a Hindu family and I have seen many ritual and spiritual things in my life. I do not practice religion. I don't go to temples but I did in my childhood, with my family, so the memory is very strong and it stays with me. Now I use it in my artwork.”

Gupta’s big breakthrough came in 2006. That year, François Pinault, the French multi-millionaire and art collector (the Paris Bourse is his) bought Gupta's sculpture Very Hungry God, (Figure 7) a very big (more than 13 feet high), very heavy (more than 2200 pounds) human skull, made of 3,000 stainless steel kitchen utensils. As one critic noted, it is dazzling for its scale and brilliance, chilling as a memento mori (Latin phrase reminding us that we all must die) Pinault displayed the skull outside his Palazzo Grassi the following year during the Venice Biennale. In 2018, it was the centerpiece for Gupta’s retrospective at the Monnaie de Paris. (Figure 8)

Figure 7. Very Hungry God (Palazzo Grassi, Venice), Subodh Gupta, 2007

Figure 8. Very Hungry God (Monnaie de Paris), Subodh Gupta, 2018

One critic has called Gupta the Damien Hirst of India. Take a look at Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God, from 2007 (Figure 9). As skulls, they are both ‘memento mori’. Both are one of a kind. Gupta fashioned his skull from pots and pans, Hirst’s is an actual human skull with actual human teeth. Gupta’s materials can be purchased by anyone, anywhere. Hirst’s skull is covered by over 8500 diamonds, including one appropriately called the Skull Star Diamond. The skull comparison mostly doesn’t work, it’s just obvious. But both artists do work with repetitions and series.

Figure 9. For the Love of God, Damien Hirst, 2007

Gupta’s exhibition at Le Bon Marché is called ‘Sangam,’ which means confluence in Hindi. It refers to the confluence of the Ganges, Yamuna and Saraswati rivers. Here is the connection Gupta makes, “Le Bon Marché is where people from all over the world meet, encounter each other and form a human river.”

Gupta also translates Sangam as a “spiritual encounter between two people, (between) several thousand people, or even within ourselves.”

“With all these people who come from all over the world, … the Bon Marché reminds me a lot of Sangam”

The people shopping at Bon Marché, as Gupta readily notes, are not his typical audience.

“The public of the place is totally different from that to which I address myself in general, because the people who will visit the store are not necessarily those who go to museums or art galleries. It is precisely in these places that art can surprise, amaze, because you don't expect to come across it there…”

He continues, “Sangam is going to be the confluence of second-hand and new objects, the confluence of two cultures, two countries, the confluence between art and the mercantile. It is an opportunity for everyone to wonder at what confluence they find themselves at.”

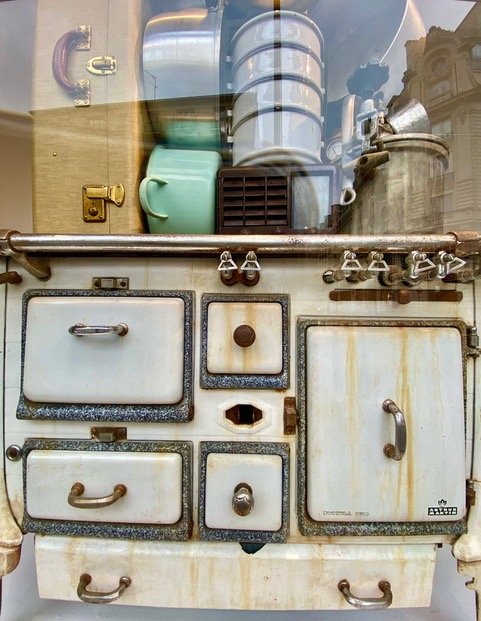

Gupta’s installation begins in the windows along the rue de Sèvres. Called ’Stitching the Code,’ each of the 10 windows is a playful cacophony of old and broken objects like plates and pots attached by cords to equally rickety furniture, like cupboards and carriage. (Figures 10, 11, 12) They all have titles, one is called ‘Eating in Proust.’ It’s the first of two references to Proust, of eating and memory.

Figure 10. Plates & Sewing Machine, Window, Le Bon Marché, Subodh Gupta, 2023

Figure 11. Pots in a Carriage, window (note Tiffin Box, front center) Le Bon Marché, Subodh Gupta, 2023

Figure 12. ‘Eating in Proust,’ window, Subodh Gupta, Le Bon Marché, 2023

Gupta’s work has been compared with Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades. And the connection is evident, especially in these 10 windows. (Figure 13) The objects and furniture Gupta used here mostly do not refer to his native India. They are an homage to his adopted home, France - objects and furniture he found at local brocantes and vide greniers and maybe abandoned on the street, too.

Figure 13. Bicycle Wheel, Marcel Duchamp, 1951

Two monumental installations greet the visitor/shopper inside the store. Sangam I is a traditional Indian pot (Figure 14) and Sangam II is a giant bucket (Figure 15). It is from the escalators going from the ground floor to the first floor and back, that you get the best views of two huge vessels made of vessels, out of both of which pour faceted mirrored glass that reflect the spaces around them. Vessels that aren’t vessels, composed of vessels that could be or have been vessels. A nod to René Magritte (Figure 16) as well as Marcel Duchamp (see Figure 13).

Figure 14. Sangam I, Subodh Gupta, Le Bon Marché, 2023

Figure 15. Sangam II, Subodh Gupta, Le Bon Marché, 2023

Figure 16. This is not a pipe, René Magritte, 1929

On the second floor, there’s an unexpected treat, a large circular hut made of Gupta’s signature saucepans. The name? ‘The Proust Effect’! (Figures 17, 18, 19, 20) It is here that Gupta hopes his visitors will linger, perhaps sit on the circular bench inside. Maybe looking at all of the cooking utensils will provoke a memory for them, a Proustian moment.

Figure 17. The Proust Effect, Subodh Gupta, Le Bon Marché, 2023

Figure 18. The Proust Effect, (detail & me) Subodh Gupta, Le Bon Marché, 2023

Figure 19. The Proust Effect, (me inside, on bench) Subodh Gupta, Le Bon Marché, 2023

Figure 20. The Proust Effect, looking up, Subodh Gupta, Le Bon Marché, 2023

For an artist who loves to cook, in a country where people love to eat well, it’s an inspired confluence. And if the connection between the culinary arts and the visual is strong enough, all visitors have to do is take themselves to the La Grande Épicerie de Paris and find something worthy of the experience. A madeleine, perhaps? (Figure 21)

Figure 21. Les Madeleines from La Grande Épicerie de Paris

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.