Strictly Street

Gérard Zlotykamien 60 ans d’Éphémères: MATHGOTH galerie, Oct.2023

Art history books tell us that modern graffiti started in the 1960s, in Philadelphia, PA. But the artist whose work we are discussing today, Gérard Zlotykamien, (Zloty), has been making his mark on the urban scene since the early 1960s, in Paris.

I saw an exhibition of Zloty’s work at the Galerie MathGoth. The directors of the gallery are passionate about urban art, and for the past 20 years have been helping and supporting street artists by discovering and showcasing their work.

The gallery is located in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, which the directors call “a district .. where urban art holds a prominent place.” Except for the names of the cross streets, of photographers, artists and writers, the boulevard along which I walked on my way to the gallery was lined with anonymous office buildings. So, when you go, do what I should have done, wander off the main street and explore.

In addition to exhibiting gallery sized examples of street art, MathGoth Gallery has been involved in the creation of several monumental frescoes in France. Because they believe that “creating a fresco on the walls of a city means improving the living environment, creating social bonds, and promoting art and culture.”

It’s interesting to read about Street Art this way, isn’t it? Do you remember when graffiti was considered a blight on the urban environment? Maybe you still think it is, although people have been making their personal marks (Fig. 1) on the impersonal environment or sometimes on other people’s property, for a very long time.

Figure 1. Ancient Pompeii, caricature of politician graffito

How did we get from blight to beautification? In the 1980s, graffiti was associated with crime and urban decay. The so-called ‘broken windows theory’ (Fig. 2) contended that a person is more likely to commit a crime in a neglected area. You know, one with broken windows, littered sidewalks, graffitied walls. To make a neighborhood safe, all the residents and authorities had to do was replace the broken windows, pick up the litter and wash off the graffiti. Except that it didn’t work. According to A. Cathcart-Leaysin (The Guardian, 2015), people began to have an epiphany, a change of heart. They began to suggest that “graffiti’s ephemeral role within the urban environment (could) actually be good for cities….” (Fig. 3)

Figure 2. Broken Windows Theory

Figure 3. Vinie Graffiti, Paris, 2021

My son, Nicolas has been a street artist for years. He does ‘tags,' ‘throw-ups,’ and ‘pieces’. I hate tags, which are a graffiti writer’s initials or street name scribbled hastily on a wall or a pole with a marker or stuck on the same with an already signed sticker. I think tags are how street artist let each other know where they are, where they have been. To me they are the equivalent of a male dog marking his territory. (Fig. 4)

Figure 4. Tags

For the throw ups (throwies) and pieces, Nicolas spends his money buying spray paint (Fig. 5) and his nights painting. In the last few years he has painted in Paris, Bordeaux, London, Athens, Rome, Copenhagen, Malmo and San Francisco. This summer, he painted four walls - one day in Christiania, Copenhagen, another with a fellow street artist, in Malmo, Sweden. In Paris, he painted one wall along the Canal St. Martin and another with a guy he met a few years ago, painting. All legal of course. (Figs. 6, 7)

Figure 5. Nicolas buying spray paint, Paris, 2023

Figure 6. Nic’s Wall, Christiania, Copenhagen, 2023

Figure 7. Nic’s Wall, along Canal Saint Martin, Paris, 2023

Like other street artists, Nicolas works out his designs beforehand. On any kind of paper, on all sorts of objects, and on my bedroom wall in San Francisco. (Figs. 8, 9)

Figure 8. Chalk tablets, letters spell M O M, Nicolas, 2023

Figure 9. Nic’s Rêve, San Francisco, 2019

Figure 9a. Rêve room with model (for scale).

Figure 9b. Mantlepiece by Nicolas, model for scale.

I was very happy to meet and learn about the work of a street artist who is old enough to be my son’s grandfather, who has been doing graffiti for 60 years.

Gérard Zlotykamien, whose street name is “Zloty,” was born into a Jewish family in 1940. When he was 2, his mother and grandmother, his uncles and aunts, were all deported to concentration camps. By that time, his father, a soldier, was already a prisoner of war. Gérard was spared the camps but spent the war years with a foster family who mistreated and abused him. Of all the family members who were sent to the camps, only his mother survived. And miraculously, his father did too. But reuniting with his parents didn’t erase the trauma that he had endured. His childhood and adolescence were marked with unhappiness, even despair.

And then he found judo, a discipline that gave him a focus, a purpose. This is how it happened. His mother was a secretary at Éditions Grasset when it published a book about judo, written by the artist, Yves Klein. Gerard’s mother got her son judo lessons. (Figure 10) Then she got him art lessons. I guess that proves that all luck isn’t bad luck.

Figure 10. The Foundations of Judo, Yves Klein

He had his first exhibition at age 18, in 1958, traditional easel paintings on canvas. But he quickly abandoned the brush and easel for the poire à lavement (enema bulb) (Fig. 11) filled with acrylic paint (soon to be replaced by the spray can). (Fig. 12) And he abandoned the studio to paint outdoors.

Figure 11. How to use a poire à lavement

Figure 12. Zloty’s poires à lavement, upper left corner, what he used before spray cans

As Zloty noted in a recent interview, artists and the street have a couple options. Marcel Duchamp, for example, found discarded objects in the street, transformed them into ‘art’ and brought them into the gallery. (Fig. 13) Zloty chose to get out of the gallery and paint directly in the streets. For a while now he has inhabited both worlds, painting outside and painting gallery size works (only sometimes on canvas) to be shown inside (Figs. 14, 15, 16).

Figure 13. ‘Fountain,’ (urinal) Marcel Duchamp, 1917

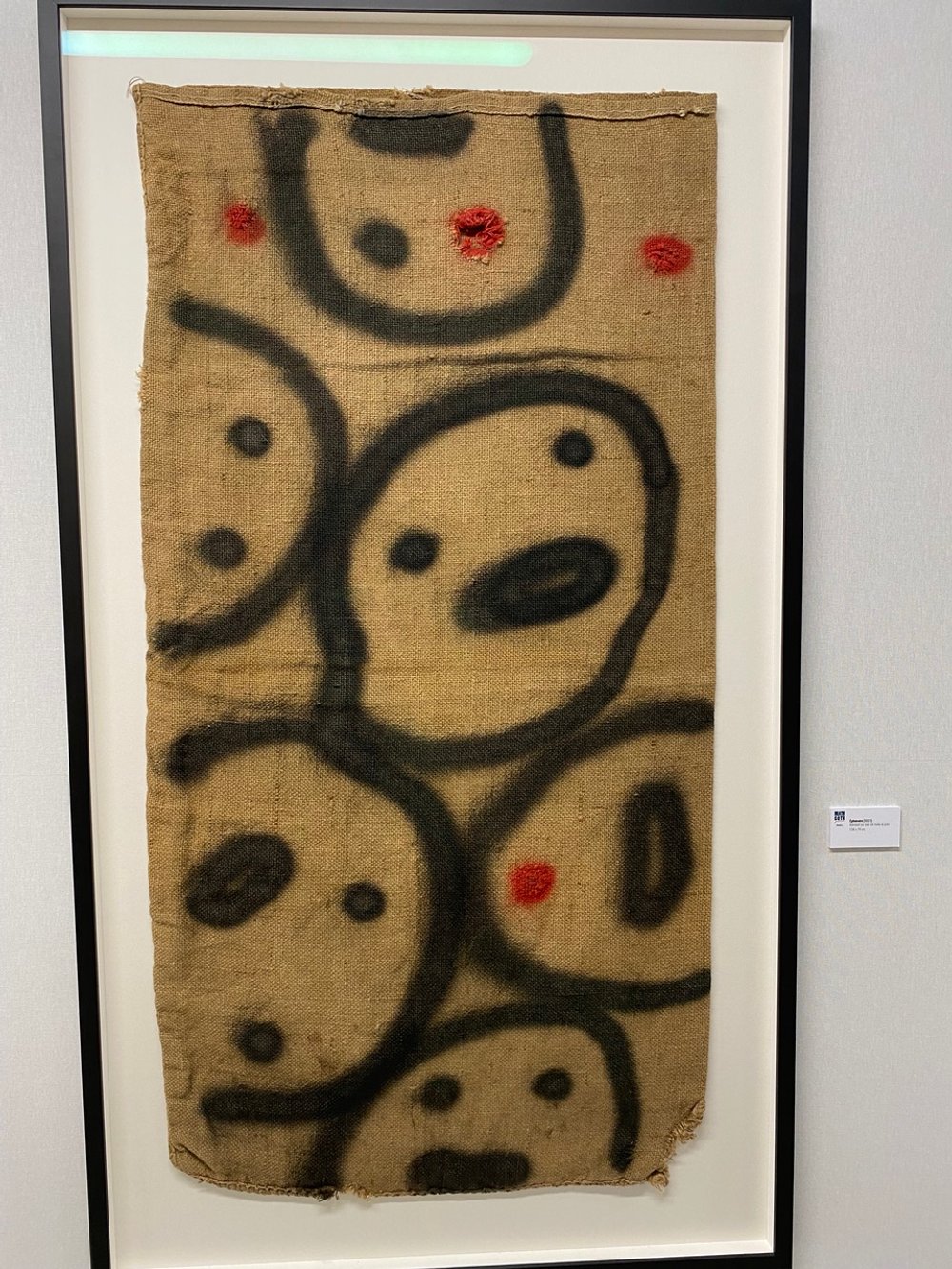

Figure 14. Burlap, Zloty, 2021

Figure 15. Éphémères, Zloty, 2022

Figure 16. Zloty, Paris, 2019

Figure 16a. Zloty, Argenteuil, 2021

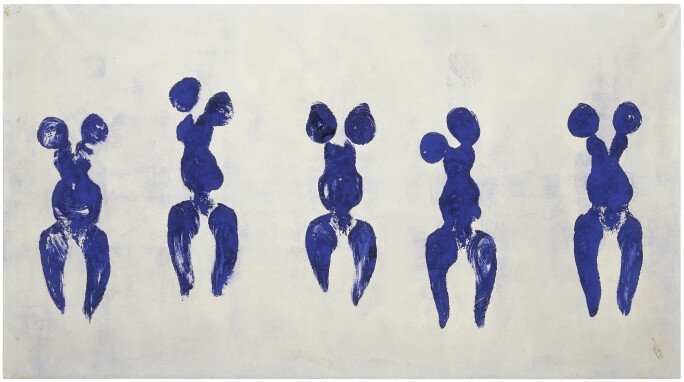

As I looked at and read about Zloty’s pieces, there were similarities between his work and Yves Klein’s ‘performance pieces,’ (Fig. 17) Between his signs and symbols and those of Joan Miro. (Figs. 18, 19) Between my son and Zloty, who both paint on anything they get their hands on. (Figs. 20, 21) And Keith Haring, who was five years old when Zloty started doing graffiti. Haring got his start scribbling on walls in New York subway stations. Like Zloty, Haring developed a visual language. (Figs. 22, 23) Haring’s was one of hope, a plea for love and understanding during the time of AIDS, to which he succumbed in 1990, at age 30. Zloty’s figural language bears witness to tragedies and traumas, the one that directly affected him as a Jewish child born in 1940 and to all the pain and suffering that has been inflicted upon innocent people since then.

Figure 17. Figures in blue, performance piece, Yves Klein

Figure 17a. Yves Klein with model.

Figure 18. Joan Miro

Figure 19. Zloty

Figure 20. Nic’s graffitied abandoned ‘Piétons’ sign, Paris, 2022

Figure 21. Street signs, Zloty

Figure 22. Keith Haring ‘It’s all about having your tags everywhere’

Figure 23. Zloty

In 1963, Zloty was commissioned to paint an exterior mural for the Third Paris Biennale at the Palais de Tokyo. (Fig. 24) The theme was the Abattoir (Slaughterhouse). Zloty’s piece was called ‘Ronde Macabre,’ or Dance of Death. It was composed of jumbled characters and disembodied faces, eyes open in horror, mouths open in soundless screams. Surely a reference to the voiceless and innocent victims of World War II.

Figure 24. Zloty painting Abattoir, Paris Biennale, III, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 1963

Figure 24a. Zloty Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2023

Zloty’s work was part of a larger installation and became an indirect victim of censorship. Inside the Abattoir, the Spanish artist, Eduardo Arroyo, had painted the portraits of four dictators: Hitler, Mussolini, Franco and Salazar. Alas, only two of them were dead. The French Interior Ministry and the Minister for Culture vetoed Arroyo’s work, considering it to be politically dangerous. This brush with censorship led Zloty to abandon institutional affiliation. He sought freedom of expression in the street.

Zloty continues to use the characters he created for the Biennale. He gave theme a name ‘Éphémères.’ Which he found one day as he was reading a Larousse dictionary. “An éphémère (mayfly) is,” according to Zloty, “an insect that lives twenty-four hours, but I think that human beings, even if they live a century, are very similar to a mayfly. When we look at what is happening in the world, we realize that life, whether it is snatched away symbolically by the disappearance of hundreds of thousands of people in a few seconds, (a reference to Hiroshima) or whether it lasts a hundred years, remains very fragile…Even if Man disappears in fifty thousand years, that will be nothing compared to the billions of years that have passed…” Zloty’s éphémères have born witness to a seemingly endless list of tragedies, among them, apartheid, genocides, Vietnam, and now, the war in Ukraine.

Zloty paints his éphémères on walls, of course, but also on typical fixtures of the urban environment, like garbage cans and fences, as well as abandoned objects like mattresses and mirrors and road signs, in the street, at recycling centers. (Fig. 25, 26)

Figure 25. Garbage can & Fence, Zloty

Figure 26. Mattress, board, fence, Zloty

Figure 26a, Chair, Zloty

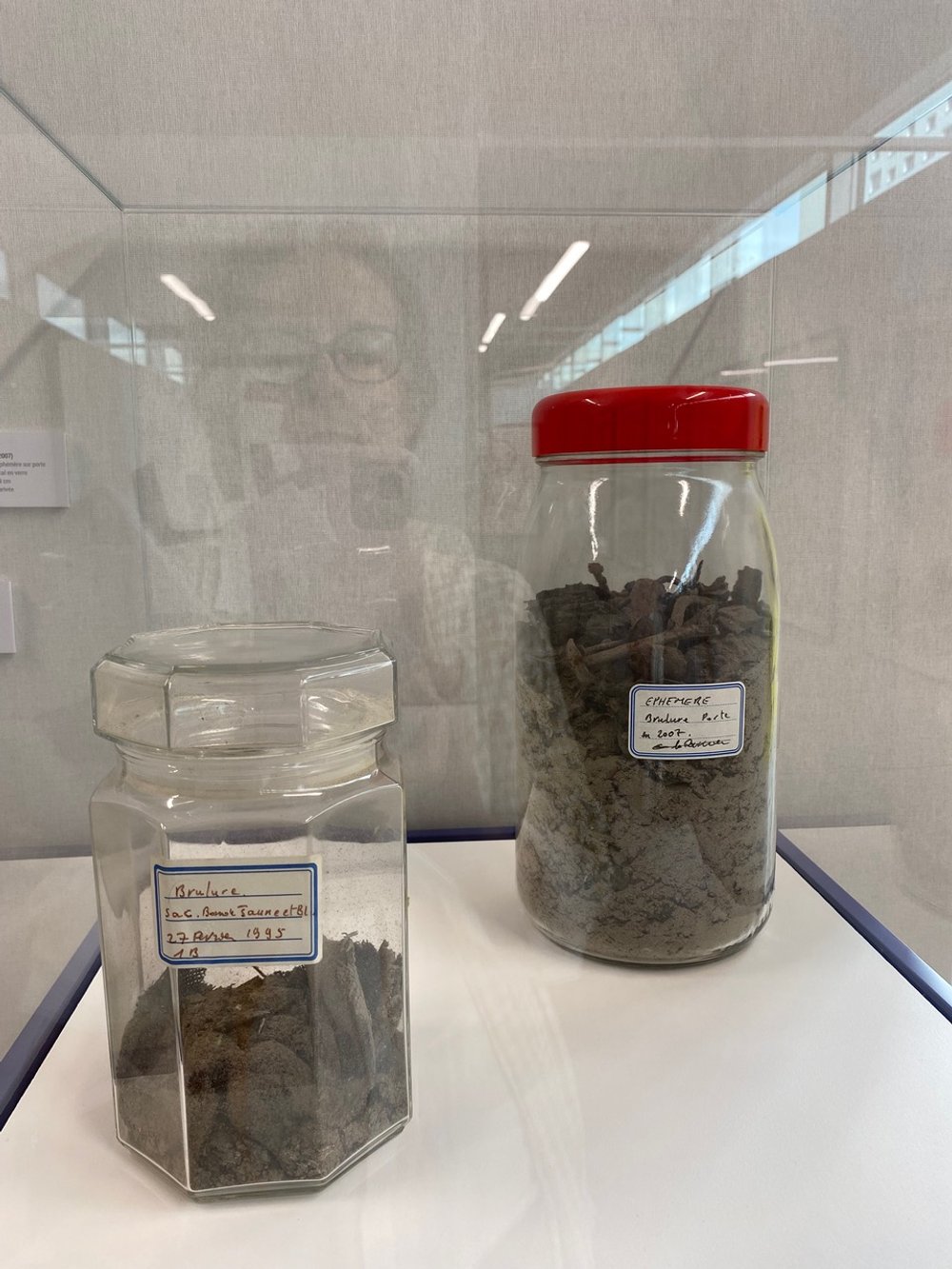

Figure 26b., Ottomon, Nicolas Held

In 1977, he created a performance piece he called Effacements. Fifteen painted, wooden planks were hung in a gallery. People came to the opening to see them. But Zloty had something else in mind. At the opening, Zloty got a roller brush and painted a layer of black paint over each of them. (Fig. 27) According to one critic, in this way, Zloty ‘recalls that the Jewish genocide represents a project of erasure of a population.’ He showed how frighteningly easy it was. He wasn’t through yet, that same year he destroyed all the works in his studio. What was left filled 18 garbage bags. Nearly twenty years later, he was at it again, he burned some old works in his garden and put the ashes in glass bottles. (Fig 28) Auschwitz and the crematoriums are never far from the artist’s thoughts.

Figure 27. Effacé, Galerie Charley Chevalier, Zloty, Paris 1977

Figure 28. Burned works in glass bottles, 1977, Zloty

In 1981, Zloty created a performance piece which reminded me, in fast motion, of what the artist, Ragnar, who represented Iceland at the 2008 Venice Biennale, did. Ragnar painted 120 paintings, one each day the Biennale was open. For an exhibition at the MathGoth Gallery, Zloty created 500 drawings in 24 hours. He did it in response to reading about government legislators working through the night, reading and voting on legislation. He wanted to experience how tired they must have been working like that. How difficult to do anything useful. I was reminded of a painting of Napoleon by Jacques Louis David which shows the emperor literally burning the midnight oil writing the Code Civile for his people as they slept. (Fig. 29)

Figure 29. Napoleon in his study writing the Code Civile at night, Jacques Louis David, 1812

Later in the 1980s, Zloty experienced the same harassment that other street artists did (see above, ‘Broken Windows’ theory). He was arrested and charged with vandalism in Germany and France. He was fined and spent time in police custody. He tried to blend in, to be anonymous, as a photo of him, from 1984 shows - wearing a brown suit, holding a briefcase, with spray paint rather than papers in it!

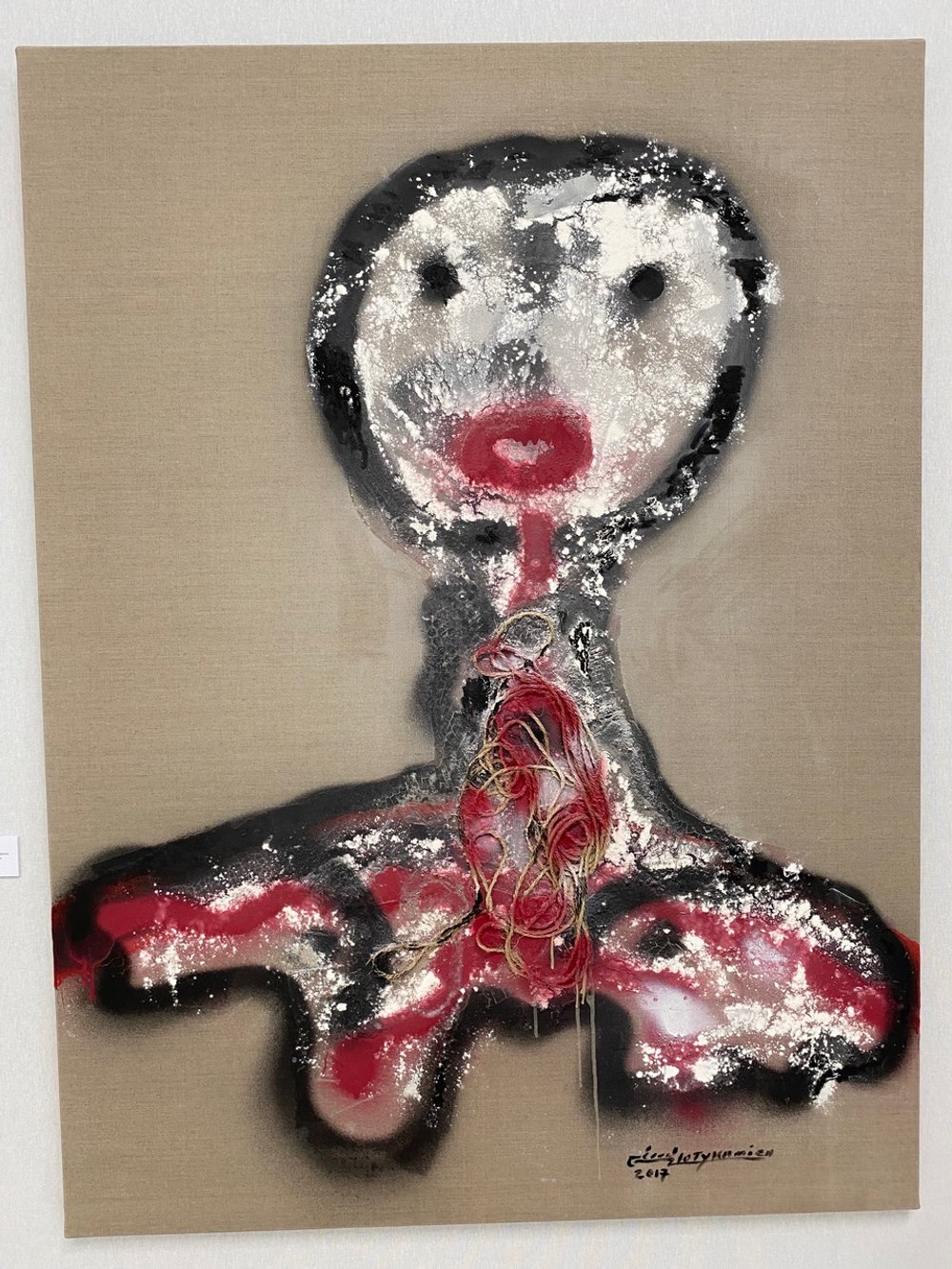

Currently he is incorporating string into his work.(Fig. 30) When asked to explain, this is what he said, “I'm working on the idea of pieces of string: I believe we are made up of a set of them. How many teachers have you had in your life? How many conferences have you attended? The pile of knowledge thus generated are so many pieces of string which mean that we are not replaceable by a computer or a robot. No one will be able to imitate you, no one will be able to be what you are, even the most advanced machine. It was Edmond Rostand who said that if he had had other teachers, other parents, or other friends, he would have been someone else.…” We all would have.

Figure 30. Éphémère with string, Zloty, 2017

Zloty, in his 9th decade holds onto despair for our collective losses but also takes time to celebrate the individuality of each and every one of us. As I read about his work and about him, I am impressed by the strength of his moral compass. If you are here, come see his work, if you can’t, it is worth your time to find out more about an artist whose principals have defined his life’s work. And continue to do so.

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.