Soutine and de Kooning together at last…

…at the Orangerie

The Orangerie is home to the art collection of garagist / gallarist Paul Guillaume. Who amassed a very nice assortment of late 19th and early 20th century French paintings before his mysterious death at age 42 in 1934. Guillaume didn’t bequeath his collection to France. His widow, Domenica did. She was initially accused of being responsible for the death / murder of her husband. It is conceivable that she made a deal with somebody and the police stopped investigating her. And she bequeathed the art collection she inherited to the State. Finding her guilty of murdering her husband wasn’t going to bring him back. Stopping the investigation was going to insure that the collection came to the State. So, that’s how that went down.

Among the many paintings in the Guillaume collection is The Baker’s Apprentice (Figure 1) by Chaim Soutine. And that painting is the beginning of this story, an exhibition which considers the work of Chaim Soutine and Willem de Kooning. Whose idea was that? Well, actually it was de Kooning’s idea. In a 1977 interview he said, “I’ve always been crazy about Soutine—all of his paintings. Maybe it’s the lushness of the paint.”

Figure 1. The Baker’s Apprentice, Chaim Soutine

I’ve written about Soutine before, but to refresh your memories: Chaim Soutine was born in a small Russian village in 1893. At the age of 13, he was beaten up very badly. But not by any of the usual suspects - the Jew baiters and Jew haters. No, Soutine was beaten up by the sons of his rabbi. For making a sketch of their father. No graven images, remember? He spent weeks in the hospital. With the 25 rubles he was awarded in damages, he got out of town. Eventually making his way to Paris.

Extreme poverty made his first 10 years in the City of Light, very dark. He lived and painted at La Ruche, the artists’ residence, atelier and exhibition space on rue Dantzig. Which was very close to the abattoir on rue Vaugirard. Which explains his paintings of animal carcasses. (Figure 2) At least one time, the stench from a decaying carcass that he was painting was so bad that fellow artists at La Ruche called the police. Ten carcass paintings survive from that period and they are among his most well-known. So, there you go. Soutine’s first art dealer Leopold Zborowski gave him a tiny stipend during the first world war, but couldn’t find anybody to buy his paintings. After the war, Paul Guillaume became Soutine’s dealer.

Figure 2. Animal Carcass, Chaim Soutine

One day in 1922, Soutine’s life changed. That day Dr. Barnes, yes THAT Dr. Barnes of Philadelphia, walked into Guillaume’s gallery and saw Soutine’s painting, The aforementioned Baker’s Apprentice which is still in the Guillaume Collection at the Orangerie. Barnes went to Soutine’s studio and bought 60 paintings for $3000 ($50,000 today). With Barnes’ imprimatur, more sales followed. But he was still the same ornery guy he had always been. And just as disorganized. He couldn’t get his papers together in time to get out of Paris. When the Nazis arrived, he went into hiding. Which is never a great idea, but even worse if you have a stomach ulcer. After awhile, the pain was too much, Soutine left his hiding place for emergency surgery. But it was too late. On 9 August 1943, Chaim Soutine died of a perforated ulcer. He was 50 years old.

Figure 3. Photo of Chaim Soutine with a friend at La Ruche (?)

But this isn’t a Soutine exhibition. This is an exhibition In which Soutine’s canvases are juxtaposed (art historian’s favorite word) with those of Willem de Kooning. Have you heard of de Kooning? Briefly, here’s his story. He was born in 1904, (eleven years after Soutine) in Rotterdam, in the Netherlands.. He left school at 12 to become an apprentice at a firm of commercial artists. In the evenings, he attended the Rotterdam Academy of Fine Arts and Applied Sciences. At 24, he left Rotterdam, stowed away on a freighter bound for Argentina. He hopped off in Virginia. And became an illegal immigrant. (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Willem de Kooning above, Chaim Soutine below.

Being from the Netherlands, he would probably have been welcomed by Donald Trump. The Netherlands not being one of those ‘shit hole’ countries and all. Why didn’t he just go to Paris as so many artists did. Which would certainly have been an easier trip. De Kooning explained it this way, “Painters flocked to Paris, while ‘a modern person’ was attracted to America”. He envisioning a career in commercial art.

De Kooning made his way to New York and supported himself doing carpentry and house painting. He befriended Jackson Pollock, Frank Kline and other young artists who, just starting out, were breaking free from the ‘isms’ of their day - Cubism, Surrealism, Regionalism. They invented their own ism along the way, ‘Abstract Expressionism’. (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Summertime, Jackson Pollock

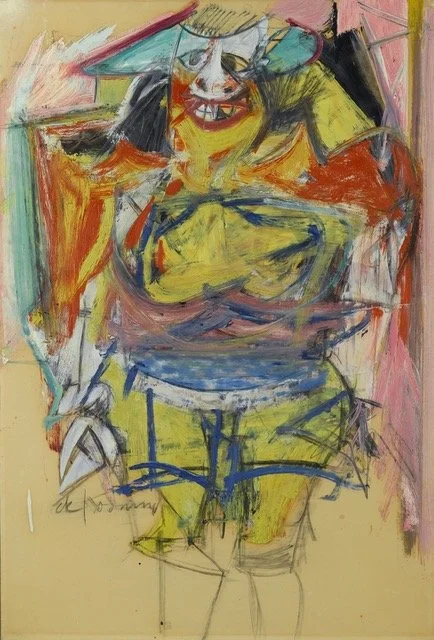

Unlike Pollock and other abstract expressionists, De Kooning never completely abandoned either the landscape or the human form. He contended that oil paint was invented to depict flesh. In fact, de Kooning is best know for the six oil paintings that comprise his Woman series (1950–53). (Figure 6) Paintings that challenge the line between figurative and abstract. The series has always disturbed me. The women’s garish faces and sagging breasts seem to have been painted with aggression and hostility. Gosh, I could be talking about Picasso. But I’m not, I’m talking about de Kooning.

Figure 6. Woman, Willem de Kooning, 1954

After the Woman series, de Kooning moved to landscape and then to a combination of women and landscape. (Figure 7) He began to make sculptures of women. (Figure 8) Which I like, I guess because they are somehow softer, less aggressive than his paintings. Maybe because there are no startling colors or hostile brushstrokes.

Figure 7. Willem de Kooning, Woman

Figure 8. Sculpture, Willem de Kooning

By his early 80s, the cumulative effect of years of drinking caught up with him. He was diagnosed with Alzheimers. But dementia didn’t seem to slow him down. Indeed, he was more prolific than ever. Eventually critics began to question how many of his paintings were being painted by his assistants.

The art historian T.J. Clark noted in Painting from Memory: Aging, Dementia, and the Art of Willem de Kooning that de Kooning “existed and painted on alcohol and tranquilizers, together or separately” for most of his career. Are the results of what you paint when drunk or drugged or both more legitimate than what you paint after you’ve been diagnosed with dementia? I don’t know the answer to that.

Okay, right, the exhibition. Which is organized this way. De Kooning’s canvases are displayed chronologically. Soutine’s are displayed in the order in which de Kooning engaged with them. That is, thematically. The curators’ idea was to establish how Soutine’s work prefigured (another favorite word of art historians) de Kooning’s. How de Kooning found inspiration in Soutine’s paintings. How he found solutions for his own paintings in them. The most obvious connection between the two artists was their love of paint, of pigment. Their paintings are as much about paint on canvas as they are about the subjects they portrayed.

These are artists whose third dimension is thick impasto coming out, coming toward the viewer. Not the creation of three dimensions using single point perspective, recession into space. But neither artist abandoned subject matter. Neither artists was looking for ways to understand the physical world like Cubism, or abandon it like Expressionism. Theirs was a ‘third way’. Holding onto subject matter, even if only tenuously, while exploring the joyful possibilities of paint qua paint, pigment for the sake of pigment.

The two artists never met. The dialogue is the one set up by the curators of this exhibition so we can see what Soutine’s paintings meant to de Kooning.

De Kooning was especially aware of Soutine’s paintings during the early 1950s when he was working on his Woman series. In 1952 he visited the Barnes collection in Merion, Pennsylvania, to see the Soutines that Dr. Barnes had purchased 20 years earlier. De Kooning recalled that “In one room there were two long walls, one all Matisse and the other all Soutine. The Soutines had a glow that came from within the paintings—it was another kind of light.”

One of the first paintings on display in the exhibition is Soutine’s Communicant (The Bride) from 1924. (Figure 9) Paired with de Kooning’s Woman II from 1952. (Figure 10) Soutine’s Bride takes up nearly the entire picture frame. Her white bridal dress is not really white at all. There are pinks, blues, greens and purples but especially yellows in it. De Kooning’s Woman II is a mix of different colors, too. Also with lots of yellows. Soutine’s bride is doe eyed and dewy, de Kooning’s Woman is provocative, her smile alluring. (Figure 11) For both artists, the pigment, the paint, is more important than the representation. Both artists distorted their subjects. De Kooning said, “Beauty becomes irritating to me. I like the grotesque. It's more joyful”. He certainly didn’t have to worry about his paintings being too beautiful!

Figure 9. The Bride, Chaim Soutine, Woman II, see above #8, right side

Figure 10 Woman II, Willem de Kooning

Figure 11. Detail of Figures 9 & 10

Celebration of paint and distortion of subject are constants, whether you are looking at Soutine’s Woman in Pink (c. 1924) (Figure 12) or de Kooning’s Woman as Landscape ( Figure 13) from 30 years later. De Kooning’s woman is in fact two faced. She has one head where you would expect it to be, on top of her neck. The other is where her belly button should be, in the center of her body. And if you put aside your effort to construct a face, a body in this composition, you can appreciate it as a landscape painting instead. Soutine plays around this way, too. Putting faces where you wouldn’t expect to find them, in his landscapes, for example. (Figure 14) As Thomas Hines notes in his review of this exhibition, “This shared sense of landscape and figure fused is perhaps the most important thing to be learned from seeing the two artists together.”

Figure 12. Woman in Pink, 1924, Chaim Soutine

Figure 13. Woman as Landscape, Willem de Kooning

Figure 14. Landscape, Chaim Soutine

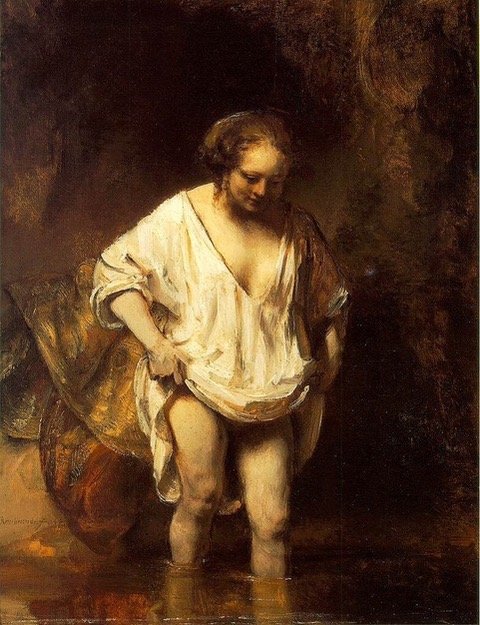

A painting by Soutine called, The Bather, (Figure 15) would be the perfect poster for this exhibition. A small reproduction of Rembrandt’s Bather is alongside it. (Figure 16) De Kooning’s Bather is here too, (Figure 17) to show us the next step. Soutine didn’t abandon the past, he studied and revered it. Likewise de Kooning didn’t follow the lead of his fellow Abstract Expressionists and denounce figurative painting altogether. Soutine showed de Kooning the way to be of his own time and at the same time, find inspiration from the past. Neither artist connected with Picasso’s Cubism or de Chirico’s Surrealism. It wasn’t logic they sought but the freedom to put paint on canvas, thick sloppy brushstrokes. Defying logic while defining form. One critic has suggested that Soutine’s complete lack of interest in the Cubists’ desire for order was exactly what appealed to de Kooning.” That sounds right.

Figure 15. The Bather, Chaim Soutine

Figure 16. Rembrandt, The Bather

Figure 17. Woman I, Willem de Kooning, 1950

Although they were both European and born only 11 years apart, their experiences couldn’t have been more different. Soutine’s demons were, from the beginning, mostly exterior ones, War and Poverty, suffered by so many artists of his generation. But beyond that, his earliest moments were forged in anti-semitism and his last years were menaced by it. From the Pograms of his youth to the Nazis at his death. De Kooning’s demons were interior. He went from undocumented alien to award winning citizen. An American success story. The embodiment of the American dream. He thrived during the American Century. His own anxieties led to alcohol and drug abuse. And of course, he lived nearly twice as long as Soutine did. He was 93 when he died. What these two artists had in common was how they approached the canvas, the paint. Both artists expressed their emotions in their work and their paintings still generate feelings in us. That’s something to celebrate!

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you