Sous (French) Su (Turkish)

Under Water at Le Bon Marché with Turkish artist

Mehmet Ali Uysal

I did find something to see the last weekend of January. Something that I look forward to savoring this cold and bleak month every bit as much as I look forward to all those slices of galette des rois. I am talking about Le Bon Marché, of course. Where every January, for the past 7, in addition to the annual white sale, there is a temporary exhibition in the store’s grand central space and in the windows along the rue de Sèvres.

The artist who created the site specific installation that greets shoppers and art lovers in 2022 at Bon Marché is the 46 year old Turkish artist, Mehmet Ali Uysal. His background is in both art and architecture, having received degrees in both subjects. He divides his time between Istanbul and Paris, having studied in both countries. And to continue the set of pairings, his works are both playful and subversive, as you will see.

The name of this exhibition is Su, the word for Water in Turkish. Although I haven’t seen any mention of it, there is surely some significance to the fact that we find ourselves SOUS, or under water in this meditative exhibition about icebergs. Wait, don’t go ….

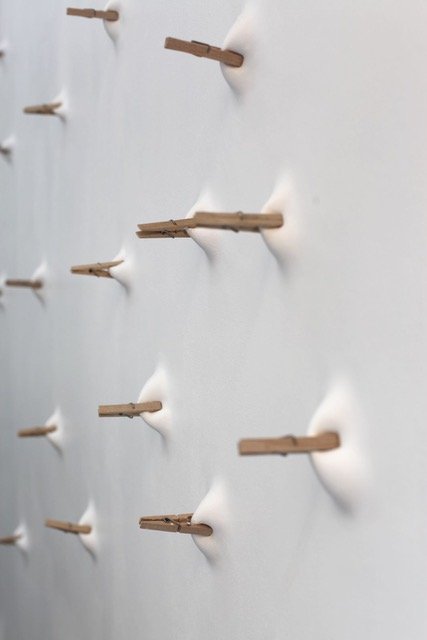

Before I tell you about this exhibition, I thought we should look at some of the artist’s other works to get an idea of what he’s about. The basic thing to know, I think, is that Uysal is not a fan of the pristine white gallery spaces in which modern art is typically shown. (Figure 1) In fact, he hates those neutral, soul-less white boxes. His mission is as much to find as many ways to subvert the box as it is to create unique works of art. Which are more often than not the confrontation with and rejection of the constraints imposed by those white boxes. Yet, even as he deconstructs the walls and subverts the space, he celebrates them both, by transforming them into works of art. After he gets to it, the gallery is no longer a cold, impersonal space but one that is filled with surprises. (Figures 2, 3) Sometimes playful but always thoughtful.

Figure 1. Typical Gallery Space

Figure 2. "Ne m'abonne pas", Mehmet UYSAL, 2020 © Photo Éric Simon

Figure 3. "Sans titre” Mehmet Uysal, 2020, © Photo Éric Simon

Here are how some critics have explained his work. "Uysal’s works explore the relationship between artwork and gallery space, manipulating both common everyday objects as well as the gallery space itself, probing our understanding of dimensions, perspective and our surroundings.” Another writes, for Uysal, the ‘walls of a gallery are not rigid, untouchable or unchangeable architectural limitations, but (the) porous and liquid elements he uses to construct and present his artistic and intellectual sensibility. And finally, “To Uysal) the exhibition space is an inseparable part of his installations. In his works the space around the art becomes part of it. The context becomes the content.” Like I said, playful and thoughtful.

Here is the second thing I noticed, his references to modern art and artists are as witty and knowledgeable as his playing around with the gallery. Among the icons of modern art I was reminded of, were Claes Oldenburg and Richard Serra and Salvador Dali.

Let’s start with an easy example. As I was looking at a sampling of his oeuvre, one sculpture struck me immediately. A giant clothespin in a public park in Belgium. (Figure 4) Of course, I was immediately reminded of Oldenburg’s Safety Pin. (Figure 5) But it wasn’t as straight forward as that, clothespin instead of safety pin, wood instead of stainless steel. The idea behind Uysel’s clothespin began as part of one of his gallery exhibition series, ‘Skin’. His clothespin is not so much in a space, as of the space, His clothespin doesn’t sit on a pedestal or hang on a wall. His clothespin does what clothespins are supposed to do, it pinches something. And that something is the wall itself. (Figure 6) Which ‘gives’ like a wet hanky. Here he is sabotaging our understanding of what a wall is, what a wall can and cannot do. And the playfulness has us rethinking materiality.

Figure 4. Uysal with his Giant Clothespin, Chaudfontaine Park, Liege, Belgium. 2010

Figure 5. Safety Pin, Claes Oldenburg, DeYoung Museum, San Francisco, 1999 - with my daughter (right) and a new friend, for scale, this past October 2021.

Figure 6. "Skin", Mehmet Uysal, 2013 © Photo Éric Simon

When Uysal moved his Clothespin from the gallery into a public park, things stayed interesting, maybe got more so. He took his clothes pin and blew it up. (see Figure 4) But the 8 foot high wooden clothespin doesn’t just sit on the grass. It interacts with the grass. By pinching it, the grass and soil underneath cannot remain passive, neutral. Like Oldenburg, Uysal plays with scale and proportion. But whereas Oldenburg’s Safety pin can go anywhere, well anywhere big enough to accommodate it, Uysal’s Clothespin really is site specific. It is this mound of dirt, this clump of grass that is pulled up. As with Oldenburg, we humans are Lilliputians in a scene from Gulliver’s Travels. But Uysal’s clothespin isn’t holding up a pair of Brobdingnagian’s underpants to dry, it is holding up the Earth’s skin itself.

Richard Serra’s work (Figure 7) came to mind when I saw photographs of one of Uysal’s pieces from his 'Peel' series.(Figure 8) Seen from some angles, the coiled sculpture looks like Serra’s monumental spirals. Peel may reference Serra in shape. But what is literally, well maybe not literally, but illusion-ily, happening, is that the plaster wall of the gallery is being peeled off, revealing the brick structure underneath. (Figure 9) The brick substructure that is traditionally hidden in buildings. As one critic noted, the bricks are construction materials to be plastered over. Except in low-income-neighborhoods where budgets don’t allow for such niceties. Or when the aesthetic is an industrial one, like the Pompidou in Paris.

Figure 7. Torsions elliptique , Richard Serra, 1996-99

Figure 8. Peel Series, Mehmet Uysal, 2012

Figure 9. Peel Series, Mehmet Uysal, 2012

There’s lots of layering in Uysal’s work. And on one level, it is a trompe l’oeil. Because Uysal hasn’t really pulled any plaster from the wall. Real plaster wouldn’t be that thick or that malleable. Which means of course, that the brick wall being revealed is also part of Uysal’s piece. The actual wall of the gallery is hidden behind the applied bricks and Uysal’s applied white wall. The piece is actually three pieces, white wall, orange brick wall underneath and sculptural object, which is the result of ‘rolling up’ the wall. ‘Peel’ is a formal and conceptual play with various types of surfaces, of walls. Underneath the partially peeled off plaster wall and underneath the brick wall of Uysal’s art piece, is the pristine white wall that Uysal is hiding, denying, subverting.

In another recent work, called ‘Suspended,' the artist riffs on the meaning and role of picture frames. (Figure 10) Picture frames usually function as a border, as a way to separate, to delineate a work of art from everything around it. But what an old fashioned and limiting concept. With Uysal, picture frames lose their functionality. Contorted and deformed to be sure, but hung on the wall as usual and transformed into a work of art. The Frames reminded me of Dali’s surrealist clocks which have also lost their purpose. (Figure 11) But which become more significant as they lose their significance.

Figure 10. “Suspended” Series, Mehmet Uysal, 2014

Figure 11. The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali, 1931

So, with that introduction, we are ready to investigate Uysal’s exhibition for Le Bon Marché. I started my visit by wandering along the rue de Sèvres. Looking into the windows which are always part of these exhibitions. Looking in was startling.The sensation is one of being under water. Evoking, according to one writer, 'the melting of the glaciers’.

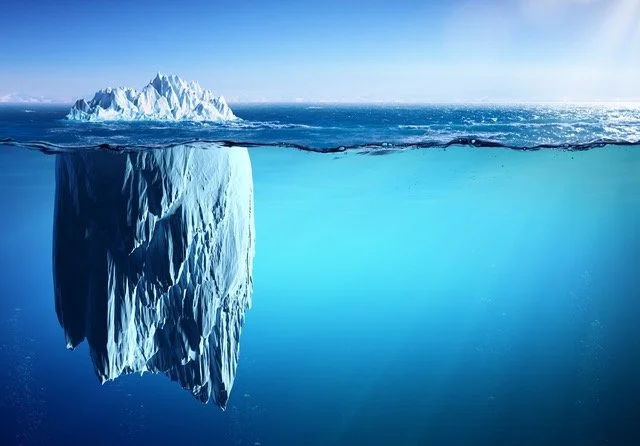

Okay, time to go inside. As soon as we enter the main space, we see two huge structures suspended from the ceiling. (Figures 12, 13) And just as we were underwater when we looked into the store windows, we are still submerged, still completely underwater. We learn that the huge structures are Icebergs. Which you remember from high school science class, are huge pieces of freshwater ice that have broken off a glacier and are floating freely in open water. (Figure 14) Uysal’s icebergs are, according to one writer, a reference to the calving process. But aren’t all icebergs a references to the calving process? They are always the result of wind or erosion or melting ice which causes the glacier to become unstable and crack. It is this ‘crack off the old block’ that becomes an iceberg. A baby in his father’s image. A huge mountain of ice in the ocean taking its own journey to nowhere. But of course, if these icebergs are the result of melting ice, then what but climate change, ocean warming, can be the culprit for the formation of these two icebergs with which we are confronted at this emporium of good taste.

Figure 12. Su Exhibition, Mehmet Uysal, Bon Marché, 2022

Figure 13. Su Exhibition, Mehmet Uysal, Bon Marché, 2022

Figure 14. Real Iceberg

Uysal’s enormous structures, made of silver fabric, are each over two meters high. (Figure 15) I watched them change as I rode the escalator up from the ground floor to to the first and then to the second floor. At each level, I got another, more intimate look at these massive structures. The are overwhelming and if they signify the overheating of the planet, if they are doomed to melt and disappear, then we are all doomed.

Figure 15. Su Exhibition, Mehmet Uysal, Bon Marché, 2022, from above

But when we get to the top, the artist offers us respite, relief. In the form of a boat, 17 by 8 meters. It’s big. And white. (Figure 16) And looks just like the origami paper boats we made as children. (Figure 17) The artist built this one for us to escape. It gives us hope. You walk onto the boat and through the portholes you see, experience, really, a choppy sea. (Figure 18) But you are no longer submerged. The portholes confirm that yes, there is water, but there is also the sky, the horizon. We’re going to make it after all! .

Figure 16. Su Exhibition, Mehmet Uysal, Bon Marché, 2022

Figure 17. How to Make an Origami Sailboat

Figure 18. Inside Uysal’s Origami Boat, ‘Su’ Exhibition, Bon Marché, 2022

Here is what Mehmet Ali Uysal said in reference to his installation for Le Bon Marché. “(L)ike many people living in cities, I had not had to face the effects of climate change directly. This summer, I experienced it for the first time… I was in Turkey where I had a workshop in the forest. For almost three weeks we were surrounded by forest fires. (T)he forest caught fire because the climate was hot and dry. That was when I realized that something was changing, both in the world and in my personal life as well….Everyone will soon notice these changes, it won’t be in 15 years, it’s imminent…’

Uysal continued, “I am not an activist, but .… I try to find out more..… (to) learn and … act at my level. I am not a politician, but I try to get involved personally … to deal with the problems.’

Uysal uses his floating icebergs to warn us. His origami Noah’s Ark provides an incentive. Ignoring facts is no longer an option, salvation lies in personal and collective action. We will be saved from the rising waters only if we are smart enough to do our part.

End of sermon. See the exhibition. It’s beautiful and important. It will do you good.

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.