Horsing Around

Me relaxing at Rose’s Café, Musée de la Vie romantique, Montmartre

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. Life seems to be filled with happy encounters and near misses. One never knows which it will be. To quote Sergeant Esterhaus on Hill Street Blues after the morning briefing, “Let’s be careful out there.”

Les Chevaux de Géricault, Musee de la Vie romantique

So, what have I been up to lately? Well, on Wednesday, I joined a press group to see the soon to be reopened (end of September) Treasury of Chartres Cathedral. It’s been closed for nearly a quarter century. The outside is still mostly a chantier (building site), but the inside is almost ready for visitors. Although we mostly concentrated on old stuff, the new stained glass windows will take your breath away. (Fig 1) I’m looking forward to sharing what I saw with you soon. I decided that the best way to do that would be to compare what I saw at Chartres with the temporary exhibition that is now on at the Musée Cluny, France’s National Museum of the Middle Ages. That exhibition is called Treasures of Oignies (until 20 October) and has been celebrated as one of the Seven Wonders of Belgium. (Fig 2) Right now, all of Paris is overrun with police cars and police vans barreling down the streets with their sirens blaring. But the Cluny was an oasis of peaceful calm and tranquility. A good place to be in Paris.

Figure 1. New Stained Glass Window, Chartres Cathedral

Figure 2. Virgin & Child (Child more interested in His thumb than His mother’s breast), Treasures of Oignies. Belgium

A week ago today, I decided to celebrate both the JO (Olympic Games) and the Quatorze Juillet. At about 5:00 p.m., I casually walked out of my apartment and nonchalantly crossed the street. My timing was perfect! I was there just as a parade of people and vehicles ran/drove by. The people, mostly young, were encouraging those of us watching to show some enthusiasm. Which we all did, in our own fashion. Accompanying these running people were vans, sponsored by Coke and Fuze, (Fig 3) filled with riding people. Finally, a young woman holding the JO flamme (torch) ran by (Fig 4). She was making her way from the Bastille to the Place de la Republique. I thought when she ran by that it was over. But people in the crowd followed her. So I did, too. Just in time to see her hand off the torch to the next runner.

Figure 3. Truck sponsored by Coke with vehicle sponsored by Fuze right behind it

Figure 4. Young woman running along Blvd Richard-Lenoir with the Olympic Torch

That evening at around 10p.m., I walked to the bridge at the Hotel de Ville (City Hall) to watch the fireworks at the Tour Eiffel. With all the barriers and porta potties, it was impossible to see anything. (Fig 5) Except lots of police walking around and lots of police vans, either parked or racing down the street, their sirens blasting. Walking home way too late after having seen way too little, I complimented myself on having made the decision to leave Paris for the Olympic Games. If it is this crowded and chaotic now, what will it be like in a couple of weeks!

Figure 5. Hotel de Ville in patriot Red, White & Blue, I mean Blue, White, Red (this is France) and their reflection

Well, that’s not why we’re here. We’re here to talk about two horse exhibitions both of which you will be able to see if you get to Paris in the next few months.

The first exhibition is ‘Les Chevaux de Gericault,’ which I saw at the very charming Musée de la Vie romantique in Montmartre. If you know Gericault at all, it is either because of The Raft of the Medusa or his compassionate and incisive portraits of people in an insane asylum. (Fig 6)

Figure 6. Portrait of a Woman Suffering from Obsessive Envy, Géricault, 1822

This exhibition was about horses, which, it turns out, were the main loves of his life and the main subjects of his paintings. And, according to the poet Théophile Gautier, “since the friezes of the Parthenon, …, no other artist has rendered equine perfection quite as well as Géricault has”. (Figs 7, 8)

Figure 7. Battle Scene, Gericault

Figure 8. Calvacade from West Frieze, Parthenon, fragment, British Museum

But first, a few biographical details. Géricault (Fig 9) was born in 1791, into a wealthy Rouenais family with whom he moved to Paris when he was 5. His mother died when they were both young. The annual allowance she left him meant that he was free to become an artist, despite his father’s disapproval. He did receive encouragement to pursue his passion for painting from his mother’s brother. Who happened to be married to a beautiful woman more than 25 years his junior. With whom Gericault had a love affair. That was a passion his uncle was not prepared to encourage. Periodic efforts to escape the mess of this quasi-incestuous relationship, saw him traveling to Rome via Florence, (1816-17) even though he had not won the coveted Prix de Rome. And then to England (1820). All this before the age of 32 because that’s how old he was when he died. Perhaps after having fallen off a horse one too many times or because he had tuberculosis or maybe syphilis. Accounts vary.

Figure 9. Théodore Géricault by Horace Vernet (one of his teachers)

I can imagine how the curators of this exhibition went about organized it. They would have started by gathering all the paintings and prints and drawings of horses by Géricault that they could find. Then they would have begun separating them into categories, themes. And then they would have put their story together. I do scholarship this way, too. Gathering images and then finding patterns and contexts.

I’m not much of a horse person and the paintings that I mostly know about horses (except for the fantastic painting by JL David, ‘Napoleon at St Bernard’s Pass’) have been mostly by English artists like George Stubbs or French artists like Rosa Bonheur. (Figs 10-12) Not my cup of tea. But this exhibition was different. The categories were interesting, the history was fascinating, Géricault’s paintings are beautiful. But now that I think about it, if I had seen paintings by either of those other artists organized like this, I might have changed my mind about the subject sooner.

Figure 10. Bonaparte Crossing St. Bernard Pass, Jacques Louis David, 1801

Figure 11. Horse & Lion, George Stubbs, 1788

Figure 12. The Horse Fair, Rosa Bonheur, 1852

The first category is ‘The Political Horse.’ Géricault grew up during the years that Napoleon’s armies were fighting war in Europe and beyond. Social status and financial security exempted Gericault from military service. But the military was in his thoughts. He exhibited in 1812, aged 21, his first painting for the Salon, an Equestrian Portrait of a military officer. (Fig 13) Two years later, having joined King Louis XVIlI’s musketeer corps which supported peace in Europe, Géricault painted Wounded Cuirassier. (Fig 14) And then Géricault began to depict “the misfortunes and atrocities of the Napoleonic Wars” with images of wounded soldiers and exhausted horses, paying “special attention to all types of horses, small and large, glorious and defeated, injured and dead.” (Fig 15)

Figure 13. Portrait équestre de M.D…, lieutenant des Gardes de l’Empereur, Gericault, 1812

Figure 14. Wounded Cuirassier, Gericault, 1814

Figure 15. Wounded Soldiers returning from Russia, Gericault

The second category is “The Stable as Sanctuary.” After studying in the studios of artists, Géricault decided that his time would be better spent studying in the stables of horses: in the barracks of the Swiss Guard in Courbevoie and the Imperial stables at Versailles. At both, he observed the “differences in race, age, strength, coat, and hair of his equine models.…” Géricault claimed that (horses) “expressed all the diversity of human psychology, as well as the power of passions and feelings.” His paintings of everyday life were paintings of everyday … horse care. The stable became both his studio and source his inspiration. (Figs 16, 17)

Figure 16. Horses and Stables, Gericault

Figure 17. Horses and Stables, print, Gericault

The third category was Rome. After losing his bid for the Prix de Rome, Gericault simply paid his own way and went anyhow. He was interested in antiquity and Michelangelo, of course. Scenes of everyday life captured his imagination, too. “(H)e drew ordinary, everyday scenes from the street, the nearby countryside, public celebrations, religious and political life.”

One of the public celebrations was at Carnival - a riderless horse race from the Piazza del Popolo to the Piazza Venezia along the Via del Corso. He was fascinated by the horses’ grooms, in their red caps, either trying to hold back or to catch up with their horses. Géricault brought drawings and sketches of the Race of the Riderless Horses back with him to Paris. The unfinished painting has disappeared. (Figs 18, 19)

Figure 18. Race of the Riderless Horses Carnival, sketch, Gericault 1817

Figure 19. Race of the Riderless Horses, Carnival, study, Gericault, 1817

The fourth category is “London: Proletarians and Dandies.” Gericault went to London in 1820 to exhibit his painting ‘The Raft of the Medusa,’ which had not found a buyer at the Paris Salon. And of course, there were horses in England, too. He was particularly struck by the duality of the equestrian world. Some horses labored and some horses raced. Géricault created a series of lithographs, which show the exhausting work performed by both men and horses. It was a theme he explored when he returned to France with depictions of horses laboring in mines. (Figs 20-22)

Figure 20. Men and Horses at Work, Gericault

Figure 21. The Coal Wagon, Gericault

Figure 22. Entrance to the Adelphi Wharf, Gericault

While he was in London, he also had access to stables through a horse dealer he knew. He made sketches of racehorses, mostly Arab, as well as stable boys and jockeys. In drawings and watercolors, he also captured the privileged world of these horses’ owners, especially the women, sitting side-saddle on their steads, in their fashionable and luxurious dresses. (Figs 23-26).

Figure 23. Portrait of Three Horses, Gericault

Figure 24. Horses and Jockeys, Gericault

Figure 25. Horses in Stable, Gericault

Figure 26. Woman sitting side saddle, Gericault

The Fifth and final category was Dead Horses. Paintings, prints and sketches of dead horses. We know that they had died by the thousands alongside the soldiers who had ridden them in battle during the Napoleonic Wars. (Figs 27-28) And then there were the horses that had been worked to death in the mines. (Figs 29-30)

Figure 27. Calvary Call, Gericault

Figure 28. Horses & Men dying in Battle, Gericault

Figure 29. Dead Horse, Gericault

Figure 30. Buzzards flying around corpse of horse in snow

There was one death of a horse that must have had special meaning for Gericault, what with the unhappy love affair with his aunt on his mind. Here’s the story. A young Polish page, called Mazeppa was discovered to be having a love affair with his master’s young wife. As punishment he was beaten, stripped and tied to a wild horse. The wild horse took off in a frenzy and eventually died of exhaustion while the young page somehow escaped. (Figs 31, 32)

Figure 31. Mazeppa, Gericault

Figure 32. Mazeppa, print after painting, Gericault

After seeing the exhibition, I wondered what art historians whose area of expertise is early 19th century French art thought. No one criticized the themes of the exhibition. What Géricault scholars were foaming at the bit about was the attribution of so many paintings and sketches and drawings as works by Gericault when they are either by unknown artists or by other artists. The director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Orléans, for example, from which two of the works in the exhibition were borrowed, wrote that works by two different artists were attributed to Géricault in the catalogue without the museum’s consent. A painting of a horse, in storage at another museum and catalogued by the museum as being “in the manner of Géricault”, is identified in the exhibition as by Géricault.

The former director of the Musée de la vie Romantique wrote a letter to the current director, which said, in part,. “…Neither the exhibition nor the catalogue meet the rigorous standards expected of an institution where precision and accuracy of information are the golden rule. … (A) reputation can be destroyed in an instant, whereas it takes years to build it up.”

Here is the current director response, “We are not the Louvre to publish a huge volume with detailed notes.”

Which infuriated, among others, the art historian Didier Rykner , who responded, in his online journal, La Tribune de l’Art (May 2024), “… Need we remind her that she is part of a public establishment, Paris Musées, which has some resources at its disposal? Need we remind her that other museums of the City, such as the Maison de Victor Hugo, which are perfectly comparable to hers, regularly publish real, scientific catalogues in which the works are described and explained? Need we remind her that before she took over as director of this museum, it had produced many catalogues with or without detailed notes, but with impeccable erudition and which are still references for art historians today? Lastly, does she need to be reminded that very many provincial museums, which ‘are not the Louvre’, also regularly publish exhibition catalogues that are exemplary in every way?

Henry Kissinger once said something like, ‘politics in academia are so vicious because the stakes are so low.’ Which doesn’t exactly work in this situation because money is involved. An auction house or gallery, using this exhibition’s catalogue, would be able to get a higher price based upon a misleading (false) attribution. Not cool.

I have to check but I do think that following all the brouhaha caused by too many inaccurate attributions, the labels on the works in the exhibition have been changed to clarify what works are definitely by Géricault and which works have been attributed to others.

And maybe that’s also why a battalion of young students from the Louvre were on hand to greet visitors and tell them about the exhibition ….

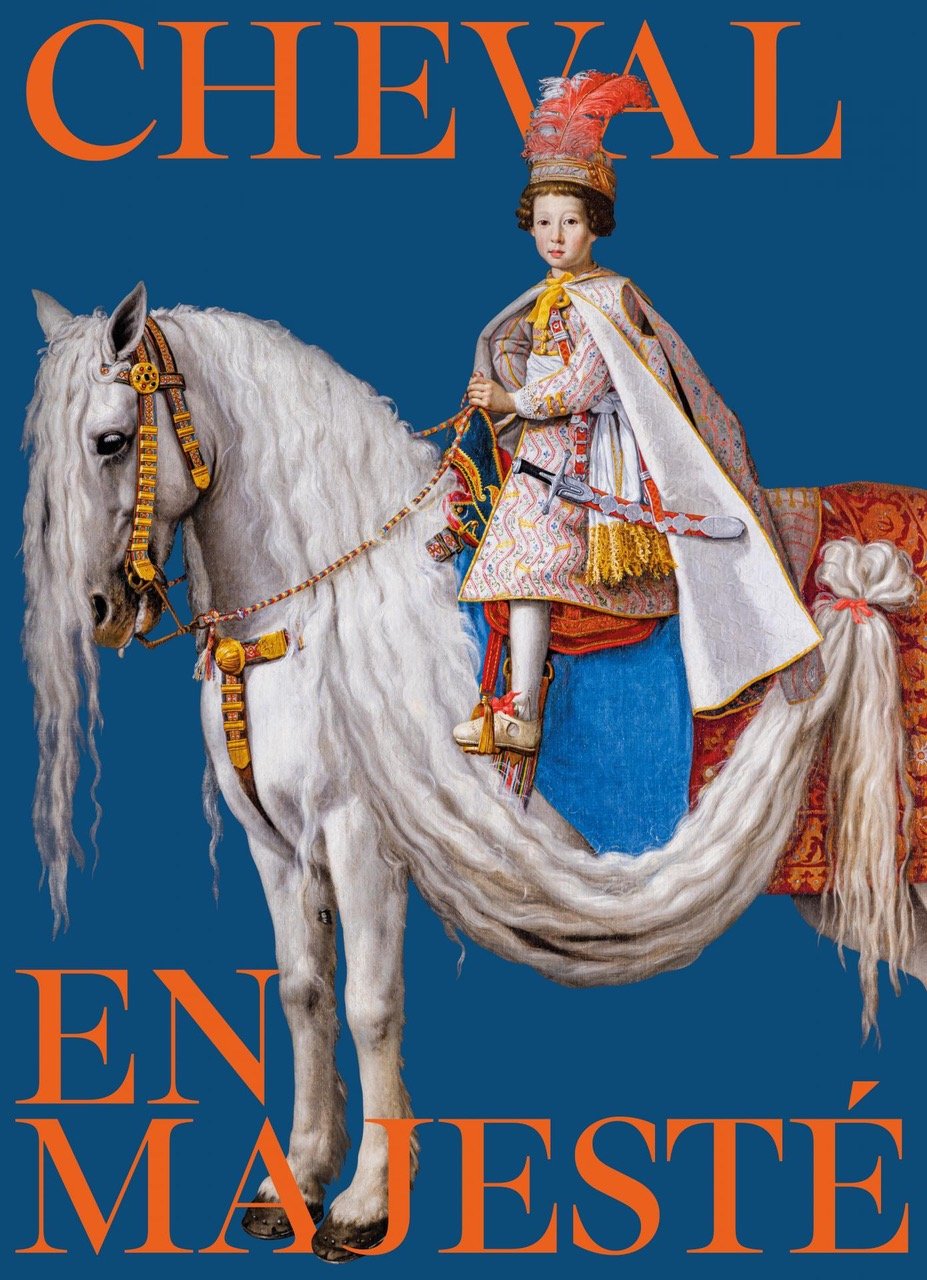

Accurate attribution of works of art was definitely not a problem with the exhibition I saw at the Chateau de Versailles, Cheval en majesté - Au cœur d'une civilization ‘(Horses in Majesty),’ (Fig 33) about which I’ll tell you next week.

Gros bisous, Dr. B.

Figure 33. Cheval en Majesté, exhibition poster, Chateau de Versailles

Copyright © 2024 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you!