Not really smelling like a rose.

Gertrude Stein & Pablo Picasso: The Invention of Language. Musée Luxembourg, until 28/01/24.

What seems like ages ago now, but which was apparently only two weeks (one in the Dordogne, one in bed with a migraine) I saw an exhibition at the the Musée Luxembourg which paired Pablo Picasso and Gertrude Stein. I wrote a brief review of it here (An Embarrassment Of Riches, start reading at Figure 12) But I wanted to explore a few more topics.

The first thing I wanted to know was how this exhibition came about, beyond the fact that everybody is commemorating the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death.

The curator of the exhibition, Cécile Debray explained it this way. She said that she “..thought it would be interesting to look back at (Picasso’s and Stein’s) friendship … and, above all, their artistic complicity around Cubism.” Debray and her colleagues were interested in exploring the links between Stein’s experiments with text and Picasso’s experiments with images. She wasn’t interested in finding their roots, but rather exploring these two pioneers’ influence on artists who followed them, to … “shed light on the immense legacy of Stein's writing, particularly on the modern and contemporary American art scene.”

What did Picasso and Stein have in common besides the fact that she was his first serious collector? She arrived in Paris from San Francisco in 1903, age 29. Picasso finally settled there the following year, age 23. She was American - wealthy, educated, Jewish, lesbian. He was Spanish - poor, gifted, heterosexual. It was their outsider status that united them, as well as their interest in making/selling/buying art.

Delbray’s bona fides are undeniable, at least so far as Stein is concerned. She co-curated an exhibition about Gertrude Stein and her family as art collectors a decade ago. That exhibition traveled from San Francisco to New York to Paris. The theme of this exhibition might also have been selected as a way to avoid the topic that has plagued Picasso scholarship for years - his relationships with women. Picasso the Misogynist doesn’t make an appearance here. Not with Gertrude Stein.

Yet his relationship with Stein is well documented, especially his 1905 portrait of her, (Fig 1) about which he said, "Everybody thinks she is not at all like her portrait. But never mind, in the end she will manage to look just like it.” Gertrude Stein agreed, ”For me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me, which is always I.” Picasso’s portrait is not in this exhibition. Andy Warhol’s riff on it is (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, 1906

Figure 2. Gertrude Stein, Andy Warhol

The exhibition begins with a selection of paintings that Gertrude and her brother Leo saw at Ambroise Vollard’s Paris art gallery. Paintings by Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris. (Figs. 3, 4) As you look at them, an audio loop plays Stein reciting her 1924 poem, “If I Told Him, A Completed Portrait of Picasso.” And so we are immediately aware of Stein as poet as well as collector.

Figure 3. Apples & Biscuits, Paul Cezanne, 1880

Figure 4. Head, Pablo Picasso, 1909

The first few lines of the poem: “ If I told him would he like it. Would he like it if I told him. Would he like it would Napoleon would Napoleon would would he like it. If Napoleon if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him would he like it would he like it if I told him.”

As an aside, a few years ago, I took a poetry course through Coursera (an online MOOC). Called ModPo, it is offered annually by Al Filreis and his teaching assistants at the U of Pennsylvania. Each week you tune into a live round table discussion with Al and his TAs. The course uses the Close Reading Method which allows everyone (even us listening in) to participate in the discussion. Ideas and opinions build upon each other. Week Four considers Gertrude Stein’s poems, including this one. If you want to know more about Stein & ModPo, here’s the link: ModPo Stein.

Stein wrote another poem about Picasso 15 years earlier, in 1909. A prose poem, entitled ‘Picasso.’ This is how it starts, ”This one was always having something that was coming out of this one that was a solid thing, a charming thing, a lovely thing, a perplexing thing, a disconcerting thing, a simple thing, a clear thing, a complicated thing, an interesting thing, a disturbing thing, a repellant [ sic ] thing, a very pretty thing. This one was one certainly being one having something coming out of him . . .”

You won’t be surprised to learn that Stein didn’t edit her work. As she filled sheet after sheet of paper with her writings she let them drop to the floor. Alice Toklas (Fig. 5) later gathered them up and typed them. Talk about misogyny!

Figure 5. Alice (in the back) and Gertrude, Cecil Beaton, 1936

Figure 5a. Portrait of Alice, Maira Kalman, 2020

Within a few years of arriving in Paris, Stein began holding weekly salons, where guys like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Picasso and Matisse, hung out. This is how it started. According to John Richardson, (NYT 1991), during the winter of 1905, Stein went daily to Picasso’s studio to sit for her portrait. “Most days after lunch, Gertrude took a horse-drawn omnibus across Paris from the Odeon (near her home on rue de Fleurus) to the Place Blanche (near Picasso’s studio at the Bateau Lavoir)… After posing for most of the afternoon, she strode down the hill of Montmartre, across the Seine (and home).” On Saturdays, Picasso accompanied her. Those Saturday evenings eventually became Stein’s weekly salon. Their relationship endured until the mid-1930s, a decade before Stein’s death. What caused the rupture? More later.

Debray contends that what Stein saw in the work of Picasso shaped her own work. That if you compare his paintings with her texts, you will see how “collage, fragmentation and the iconography of everyday life are at the heart of the painting of one and the writings of the other.” (Figs. 6, 7)

Figure 6. Guitar (of found objects), Picasso

Figure 7. Tender Buttons, Gertrude Stein, 1914

Debray didn’t convince everyone. Joseph Nechvatal (Whitehot Magazine, 2023) suggests that “a more fruitful dialogue would have been between Marcel Duchamp’s idea-based work (Fig. 8) and Gertrude Stein’s language-based work…” And beyond that, the repetition, found object re-contextualizing (and) rehashing, …in Duchamp’s art and Stein’s writing more strongly resonated into the second half of the 20th century than Cubism.”

Figure 8. Readymades, Marcel Duchamp

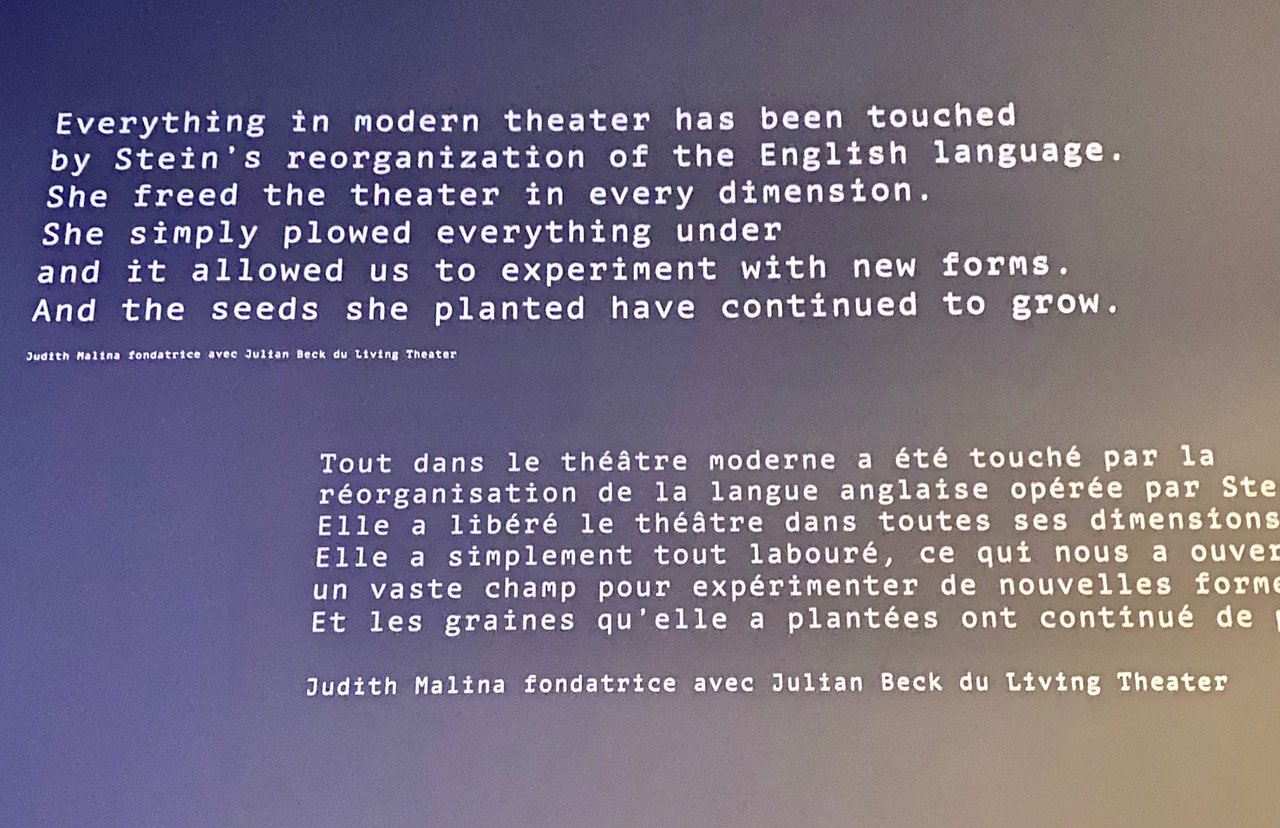

Maybe the Stein/Picasso/Cubism connection isn’t totally convincing, but Stein’s influence on generations of artists who followed her, is undeniable. Especially since wall texts throughout this section, the “American Moment” section, include testimonials from these American artists, (Fig. 9) The curators show how Stein’s experimental verse and repetitive writing inform theatrical, musical, choreographic and visual art in America. Clips of a variety of performances are here as examples. Starting with the 1933 opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, (Fig. 10) libretto by Stein, music by Virgil Thomson, costumes and stage sets by Florine Stettheimer (the subject of an exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York a few years ago). Then moving on to performances by dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage, set decorations by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg (Figs 11, 12).

Figure 9. Judith Malina, founder of Living Theater on influence of Gertrude Stein

Figure 10. Four Saints in Three Acts, Stein (libretto) Thomson (music) Stettheimer (decor & costumes)

Figure 11. Minutia, Cunningham (choreographer) Cage (composer) Rauschenberg (sets)

Figure 12. Minutia, Rauschenberg (set)

Works by visual artists like Bruce Nauman and Nam June Paik are also here. (Figs. 13, 14) Perhaps because I love words so much, I just couldn’t get enough of all the convoluted and clever and sometimes silly and sassy ways words are stretched and chopped and reassembled in so many of the art works in this exhibition. There was a bank of clocks by Joseph Kosuth called ‘Quoted Clocks.’ (Figs. 15, 16) On each of these standard analog clocks, a quotation from an author or philosopher adds meaning to what would otherwise be the simple passing of time. At the bottom of each clock face is an inscription, ‘Existential Time’ with various dates and locations.

Figure 13. Study for Pleasure, Pain, Life, Death, Love, Hate, Bruce Nauman, 1983

Figure 14. Gertrude Stein, Nam June Paid, 1990

Figure 15. Quoted Clocks, Joseph Kosuth, 2020

Figure 16. Is it later yet? Jennifer E. Smith, Quoted Clocks, Joseph Kosuth, 2022

Figure 16a. 'Make it a mistake’ Gertrude Stein, ‘Quoted Clocks, Joseph Kosuth, 2022

I mentioned above that Stein and Picasso remained friends until the mid-1930s. What happened? I’d say ideology and politics. In 2021, I saw an exhibition at the Musée de l’Immigration called ‘Picasso the Immigrant’. The exhibition’s curator, Annie Cohen-Solal tells us that as early as 1901, when he was still traveling between Barcelona and Paris, Picasso was under surveillance by the French police. She offers three reasons. “(F)irst, he was a foreigner; second, he was considered an anarchist; and third, he was avant-garde in a country that was horrified by the avant-garde …”

When Picasso applied for French citizenship in 1940, a deputy inspector general of the Police Prefecture denied the application. According to the inspector “This foreigner does not meet any of the requirements for naturalization; …..” This denied application hung over him until the end of the war. As an enemy alien, he could have been detained, deported to Franco’s Spain, where his anti-Fascist, anti-Franco politics were well known. His painting Guernica is proof of that. (Fig. 17)

Figure 17. Guernica, Picasso, 1937

Even thought his own situation was perilous, in 1940, he offered to sign a letter protesting the incarceration at Drancy of his dear friend, Max Jacob, (Drancy was the French detention camp from which Jews were deported to Nazi extermination camps). In 1946, he helped organize a benefit auction of paintings, including his own, for Berthe Weill, the Jewish gallerist who was destitute after years of hiding during World War II.

What about Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas. (Fig. 18) What did they do during the war? I have always wondered how two Jewish women were able to live in France when so many French Jews, some of them very wealthy, some of them very connected, were rounded up and sent to the death camps.

Figure 18. Gertrude & Alice

Figure 18a. Gertrude & Alice and poodle

Enough people who saw the Stein exhibition in New York a decade ago wanted to know the same thing. So the exhibition curators added a block of wall text which, according to the NYT, “acknowledge(d) questions that have long surrounded Gertrude Stein’s sympathy toward the Vichy regime during World War II, leanings that might have contributed, amid Nazi looting during the war, to the survival of many of the works in the show.”

Stein’s conduct during the war was the subject of a piece Janet Malcolm wrote for the New Yorker in 2007 (later a book) and a book that Barbara Will wrote in 2011. Both authors discuss Stein’s politics and especially her relationship with Bernard Faÿ, who is described by Allen Ellenzweig (Tablet , 2012) as a “connected anti-Semite collaborator, committed Catholic, and conflicted homosexual.” Stein and Faÿ became friends in the mid-1930s. It was Faÿ who “personally interceded on (Stein’s) and Alice’s behalf with Maréchal Pétain” so they could stay in France unharmed during the Occupation. And it was Faÿ, “as director of the Bibliothèque Nationale during the Occupation, (who) secured Stein’s Paris art collection from the Germans.”

How did Stein endear herself to Faÿ, to the Vichy government and to the Nazis? How about this for a start: She wrote deeply conservative pieces for magazines during the 1930s; she supported Franco and was against the Republican cause in Spain; she hated Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal in America. In 1934, she said in an interview that Hitler “should have received the Nobel Peace Prize … (for) removing all elements of contest and struggle from Germany. …”

Wait, there’s more, from 1941 to 1943, she translated Pétain’s speeches into English for Faÿ, who was hoping to sway the American public in favor of Vichy. Faÿ later “became an active Gestapo agent whose intelligence-gathering against French Freemasons ultimately aided in many deportations and deaths…” Even after the war, when Faÿ was put on trial for war crimes, Stein wrote to the court on his behalf. Even after Stein’s death, Alice, with much less money than before, spent some of it trying to assist Faÿ.

So, while Picasso was being hounded by the French authorities, Stein was ingratiating herself to the Vichy government. His position was tenuous throughout the war. She and Alice were safe and her art collection was, too. The more you know …. the more you know.

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.