Mondrian before Mondrian

Mondrian Figuratif, Musée Marmottan Monet

I remember the first time I went to the Musee Monet Marmottan, it seemed like the ‘bout du monde’ (end of the world), it was so far from the 6th arrondissement where I always stayed. Now that I live in the 16th, it is my neighborhood museum. And it really isn’t so far from the center of the world, aka the 6th, as I had thought. So, that is one worry over.

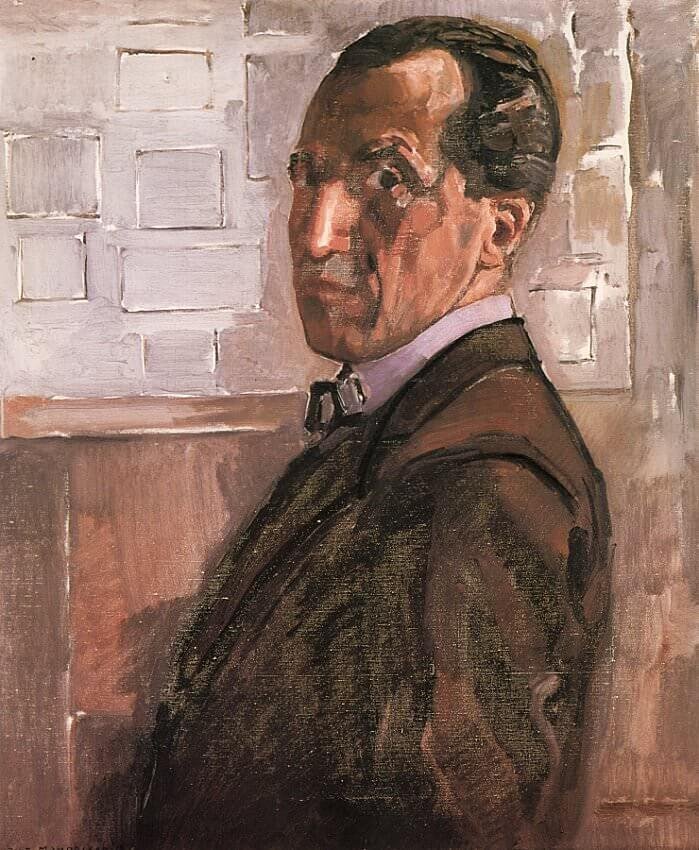

Figure 1. Piet Mondrian - Self Portrait, 1918

Figure 2. Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1943

Now, if you are worried that the current exhibition of Mondrian’s figurative painting is just canvases inspired by Dutch landscapes, let me ease your mind on that score, too. (Figure 1) There are a few more or less tradi- tional paintings, but this is one artist who rocks out and explores the possibilities of colors right away. While it is true that you are not going to find Broadway Boogie Woogie (Figure 2) or the inspirations for Yves Saint Laurent here, (well, there is one red, yellow, blue painting at the end) (Figure 3) you are going to see an artist who departs from ‘rational’ colors and offers up some pretty gorgeous paintings.

Figure 3. Yves Saint Laurent - Mondrian Dress,(1966)

Just as the Marmottan is the largest collection in the world of Monet’s works, a result of the donation in 1966 by Michel Monet, Monet’s only surviving heir, this collection of Mondrian’s paintings is the result of a single collector, a man called

Figure 4. Henri van de Velde, Portrait of Sal Slijper, 1930

Salomon Slijper. (Figure 4) Slijper met Mondrian in 1915, in Laren, an artists’ village in the Netherlands. Mondrian had already moved to Paris but was visiting the Netherlands when war broke out. Turns out that being stuck there changed Mondrian’s life since Slijper became a passionate collector of his work. Although by the time Mondrian met Slijper, he had begun his abstract paintings, it was the figurative canvases that Slijper paintings in the Rijksmuseum to survive. With Slijper’s financial support, the artist returned to Paris (1919) where he found his studio just as he had left it four years earlier. He packed up and sent all his naturalistic and Cubist paintings to Slijper, who paid 965 guilders for the lot.

This exhibition is intended as a celebration of the collector, so a few words about Slijper. He was the son of a Jewish diamond merchant who became financially independent upon the death of his father. He began to collect art but the 1929 stock market crash ended that. Instead of selling his art collection, he sold his grand house. When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Slijper, one of a small minority of Dutch Jews to survive the Holocaust, hid in his home, with the help of his housekeeper who risked her own life to protect him and whom he later married. Slijper’s Mondrian collection survived the war hidden in a neighbor’s attic, another courageous act, since storing Jewish property could have resulted in imprisonment or deportation.

What about the paintings I hear you asking. Okay, let’s talk about them. But first, maybe you should know where Mondrian was coming from. As early as 1908, he was devoted to Theosophy, a philosophy that sought a spiritual understanding of nature that transcended empirical observation. In 1914, he wrote "Art is higher than reality and has no direct relation to reality. To approach the spiritual in art, use (realty) as (little) as possible because reality is opposed to the spiritual.” And that is what he did. Yet the natural world is found in nearly all of the paintings exhibited here.

Figure 5. P. Mondrian, Mill in Sunlight 1908

Figure 6. Piet Mondrian, Red Mill, 1911

A few subjects are treated multiple times: the mill, the lighthouse, the church. In Mill in Sunlight, painted in 1908, (Figure 5) the windmill is composed of vertical red lines over a blue field. A sense of depth is created by the arms of the windmill, in 3/4 view. The base of the windmill bleeds into the ground - flecked yellow and red brush strokes reminiscent of Van Gogh. The background is a shimmering yellow honey cone pattern atop a pale blue sky. Three years later, Red Mill (Figure 6) is pure geometry - a vertical shape, its arms chopped off by the canvas, solid red against a solid blue field with the slightest variation to mark the transition between ground and sky. In Church at Domburg painted in 1909, (Figure 7) we see a corner of the church windows on both sides defined by a series of horizontal ‘taches’ mostly yellow with orange dots.

Figure 7. Piet Mondrian, Church at Donburg, 1909

The Pink Church, (Figure 8) painted in 1911, is pure facade or shell with openings, doors, windows, onto the green and blue sky beyond. The more you look at these paintings, the more you see.

Figure 8, Piet Mondrian, Pink Church, 1911

One final note, the exhibition ends with six paintings of single flowers dating from 1918- 1921. One example is Lily, (Figure 9) painted in 1921. Compare that to the flower Mondrian chose to paint, another lily, this one, Arum Lily from 1908. (Figure 10) When Mondrian was unable to sell his abstract paintings, Slijper suggested that he have paintings of single blooms available in his studio. And so he did, painted quickly and sold cheaply, these flowers enabled the artist to continue developing his theories and painting his abstractions.

Figure 9. Piet Mondrian, Lily, 1921

Figure 10. Piet Mondrian, Arum Lily, 1908