Mission Accomplished - Julie Manet as Champion & Collector.

Julie Manet La Mémoire Impressioniste. Musée Marmottan-Monet

I’ve written about a couple temporary exhibitions at the Musée Marmottan-Monet over the past couple years. But I haven’t written about the museum itself. Which is fortuitous since the exhibition there now, unlike those other exhibitions, has close ties to the museum. Indeed its focus is on part of the museum’s permanent collection.

The exhibition, Julie Manet: An Impressionist Heritage is not an exhibition about Edouard Manet’s wife or daughter. It is an exhibition about his niece, the daughter of his younger brother, Eugène. And Eugène’s wife, the painter, Berthe Morisot. Who may have been in love with Edouard but who married his brother. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. ‘Repose,’ Portrait of Berthe Morisot, Edouard Manet, 1871 (Rhode Island School of Design)

If you’ve been to this museum, most likely it was to see the Monet’s on the ground floor. (Figure 2) And the Berthe Morisot paintings on the first floor. And as you went from one to the other, you surely noticed paintings by other Impressionists (Figure 3) and some medieval manuscript illuminations and some early Renaissance paintings. And some Napoleon stuff and some furniture, too. Quite a range. (Figure 4)

Figure 2. Claude Monet room, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris

Figure 3. Rue de Paris, Temps de Pluie, Gustave Caillebotte, 1877 (gift of Michel Monet)

Figure 4. Musée Marmottan-Monet, Interior

The museum’s story begins with Paul Marmottan, the only son of Jules Marmottan. From whom he inherited a substantial fortune, a Parisian hotel particulier (Figure 5) and an art collection. Jules Marmottan collected German, Flemish and Italian primitives. Paul added to it with his own collection of First Empire paintings, sculptures and furniture. Paul bequeathed the mansion and his art collections to the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The museum opened in 1934, two years after his death.

Figure 5. Musée Marmottan-Monet, exterior

The Académie des Beaux-Arts, which inherited Marmottans’ collections was founded in 1648 (as the Académie Royale de Peinture) to champion French art. Through teaching and annual (or bi-annual) art exhibitions, the Salon. The Académie was devoted to preserving the nation’s artistic tradition. As they defined it.

Marmottan was not a fan of the artists of his time. In 1886, he wrote that Impressionists “don’t draw, they sketch, don’t paint, they brush”. Marmottan could have been a spokesperson for the Académie which kept a very tight lid on what was permitted (very little) and what was rejected (anything new) from Salon exhibitions.

How then did the largest collections of Claude Monet and Berthe Morisot find their way here? First, a little history. In1863, when nearly half the paintings submitted to the Salon were rejected by the Academie, Napoleon III authorized the Salon des Refusés, for the artists who had nowhere to show their work. Among the exhibitors were Cezanne, Pissaro, Whistler and Manet, who exhibited his “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe,” (Figure 6) officially regarded as a scandal, an affront to good taste.

Figure 6. Déjeuner sur l’herbe, Edouard Manet, 1863 (Musée d’Orsay)

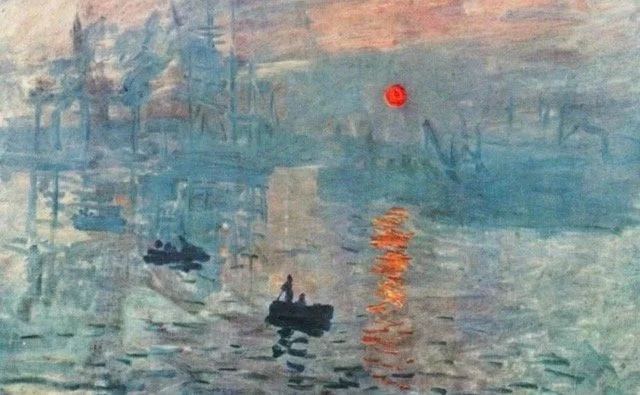

In 1874, a group of young artists, who later became known as Impressionists exhibited their work independently for the first time. Monet exhibited his ‘Impression Sunrise.’ (Figure 7) The critic Louis Leroy called the work an Impression. It was not a compliment.

Figure 7. Impression Soleil levant 1872, Claude Monet, 1872 (Musée Marmottan-Monet)

Exhibiting independently was radical and risky. No group of artists had ever done it before. But between 1874 and 1886, the group held eight major exhibits that included some of the best-known artists (to us) of the time. Of course, there were internal rivalries and off-shoots and not everyone exhibited every year but these exhibitions marked the turning point for art marketing.

And then, just 8 years after Paul Marmottan’s death, in 1940, the museum acquired eleven impressionist canvases, including the painting by Monet that gave the group its name. How did that happen? A donation, of course. From the daughter and heir of Dr. De Bellio, a wealthy homeopathic physician whose patients included numerous impressionist artists. As he ministered to their health, he collected their paintings. Sometimes in lieu of payment. That bequest and another in 1957 became the foundation of the Museum’s Impressionist collections.

Michel Monet, Claude Monet’s sole heir was next. He donated paintings, including some from his father’s monumental Water Lilies series. Claude Monet had already donated some of the 125 large panels to France. These were installed in the Orangerie, and following Monet’s wishes, they weren’t exhibited until the year after his death in 1926. They were not well received. When Michel tried to sell other paintings from the series, none of the national museums of France wanted them. Which was why he didn’t bequeath either the paintings or the house at Giverny that he inherited. Instead, Michel donated everything to the Musée Marmottan.

When Michel died, in 1966, a room was built under the garden to accommodate the Water Lillies. And the museum became the Musée Marmottan-Monet.

Ironic, no? Two equally conservative entities, the initial donor, Paul Marmottan and the Academie wind up with the largest collection of Monet paintings in the world.

Other artists’ heirs followed Michel Monet’s example. Most significant for our tale is the bequest by the Rouart family, Berthe Morisot’s daughter Julie and Julie’s husband Eugène Rouart. In 1993 and again in 1996, the family donated paintings by Berthe Morisot and paintings that Morisot collected to the Musée Marmottan-Monet. (Figures 8,9)

Figure 8. Portrait of Eugène Manet, Isle of Wight, Berthe Morisot, 1874, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Figure 9. Claude Monet Reading, Auguste Renoir, 1868, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Berthe Morisot wrote in her diary in 1890, (she was 51 years old) “I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal, and that’s all I would have asked for—I know I am worth as much as they are.” Sing it to me sister!

Morisot was born into an affluent bourgeois family. Like many women of her class, she had taken art lessons as a girl because drawing, like needle point and playing a musical instrument, were accomplishments expected of a young woman of means. When Morisot displayed real talent, her teacher cautioned her family against continuing her studies. It wasn’t ladylike, it could damage her reputation.

Yet both Berthe and her sister Edmé continued their studies. They both showed promise. When Edmé left home in 1869, aged 30, to marry, it was the first time the sisters had been separated and the last time Edmé painted seriously.

Berthe stayed home, single, independent. She participated in the Salon des Independants, in 1873, the only woman to do so. (Figure 10) The following year, Morisot’s resolve weakened when her father died and with him, the family’s source of income. She was going to have to fend for herself. Marriage seemed the only solution. Her brother Tiburce thought it was a terrible idea. He wrote, “For the love of God, if you are thinking of getting married, don’t end up with this idiocy and contradiction of a marriage of pure convenience. You could have done that at 18 when your character can be broken and your ideas sapped … for heaven’s sake, have a little courage!”.

Figure 10. Le Berceau, Berthe Morisot, 1872, Musée d’Orsay

As it turns out, the woman who modeled most frequently for Edouard Manet (he painted 12 portraits of Morisot), married Edouard’s brother, Eugène. She might have been in love with Edouard but he was already married, (to his piano teacher, long unsavory story, we’ll save it for another time). Édouard painted his final portrait of his future sister-in-law in 1874, shortly before her marriage to his brother. She wears black lace, like the sitters in paintings by Manet's favorite artist, Velázquez. She may not be looking at the painter but she is flaunting the ring on her finger. (Figure 11)

Figure 11. Portrait of Berthe Morisot, Edouard Manet, 1874, Le palais des beaux-arts, Lille

When Berthe Morisot married Eugène, she was 33, he was 41. On their marriage license the bride was listed as “without profession.” Yes, but… she continue to paint and she continued to sign her work with her maiden name. And as it turned out, Eugène Manet was content to encourage and support his wife in her work.

Berthe hadn’t expected to marry. And she probably hadn’t expected to get pregnant. And yet, at age 37, she gave birth to Julie.

The more than 130 paintings, sketches, drawings, photographs, letters & etc. in the exhibition show the creative circle into which Berthe Morisot's daughter was born and grew up. And which surrounded her and loved her when tragedy struck.

Uncle Édouard painted her at 15 months. (Figures 12, 13) Her mother painted her over and over again. (Figures 14, 15) Morisot described Julie as being “like a little cat, always in a good mood”. When she was nine, Renoir painted ‘Julie with a cat’. Their expressions are the same. (Figure 16)

Figure 12. Julie at 15 months. Edouard Manet, 1879 (private collection)

Figure 13. Julie sur l’Arrosoir,, Edouard Manet, 1882 (private collection)

Figure 14. Eugène and Julie Manet, Berthe Morisot, 1881, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Figure 15. Self portrait with Julie, Berthe Morisot, 1885.

Figure 16. Julie with a cat, Auguste Renoir, 1887, Musée d’Orsay

Morisot may have been married but she still couldn’t hang out in cafés with her male colleagues. So, she held weekly salons at her home. And her guests included her brother-in-law and their friends, like Degas, Monet and Renoir who called it “one of the most authentic centers of civilized Parisian life, where even Degas became more civil.”

Julie’s father Eugène Manet died in 1892. The poet and family friend, Stéphane Mallarmé, gave Julie a greyhound dog to comfort her. That year, Morisot painted her daughter in mourning, her pet dog by her side. (Figure 17)

Figure 17. Julie and her dog, Berthe Morisot, 1893, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Julie’s mother died three years later. The day before her death, Berthe Morisot wrote to her precious girl, “My little Julie, I love you as I die; I will love you when I’m dead... you haven’t made me sad once in your little life….” (Figure 18)

Figure 18. Berthe Morisot and daughter, Julie Manet, sketch, Auguste Renoir, 1894

With her parents gone, Julie began calling herself, ‘the last of the Manets’. On the first anniversary of her mother’s death, a retrospective exhibition of her work opened at the Durand-Ruel Gallery. The exhibition, which included over 400 paintings, pastels, watercolors, drawings, and sculptures was organized by Morisot’s friends. Mallarmé wrote the catalog, Monet, Degas and Renoir hung the works and Julie labeled them, providing the foundation for the eventual catalogue of her mother’s work.

Julie painted, encouraged first by her mother and then by Renoir. She exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1896 and 1898. (Figure 19) By then, following her mother’s instructions, Julie was living with her cousins, Jeannie and Paule Gobillard, daughters of Morisot’s elder sister, Yves, also orphans. Stéphane Mallarmé and Edgar Degas became Julie’s and Jeannie’s guardians.

Figure 19. Julie Manet, Jeune Fille au chien, 1898,

The girls may have been independent, traveling so frequently that Mallarmé called them the ‘Flying Squadron,’ but the confirmed bachelor Degas and Mallarmé made sure that their charges didn’t follow the trail-blazing path of Julie’s mother. Those two men weren’t going to let these two girls remain husbandless if they could do anything about it. And they could. And they did.

One of Degas’ friends was the wealthy art collector, Henri Rouart. He organized a meeting between Julie and his friend’s son, Ernest, his pupil. According to her cousin Jeannie’s diary, one day, Degas invited Julie and Ernest to his studio. He asked Julie if she would marry Ernest. She said yes, but only if Ernest asked her himself. He did. She accepted.

Jeannie, the recipient of Mallarmé’s equally insistent match making, married Mallarmé protégé, the poet Paul Valéry. The young women married their grooms in a double wedding ceremony in 1900. The brides wore identical gowns and the grooms wore identical cutaway jackets. (Figure 20) They lived on two floors in the same apartment building on rue de Villejust (now rue Valéry) in Passy.

Figure 20. Julie and cousin Jeannie, Ernest Rouart & Paul Valéry, Wedding Day, 1900

Her marriage to Ernest Rouart brought Julie into a family of collectors. And the couple worked tirelessly to secure a place in art history for both Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot. They knew that the best way to do that was to make sure examples of both artists’ paintings were in the permanent collections of museums. Their goal wasn’t to sell paintings but to donate them. Everybody who could participate, did. For example, Paul Valéry's brother knew somebody who knew somebody at the Fabre Museum in Montpellier which agreed to accept Morisot's painting, ‘Young Woman in front of the window called “Summer ”. (Figure 21) In 1930, following up on one of her mother’s wishes, Julie donated her uncle’s La Dame aux évantails to the Louvre. (Figure 22) Berthe Morisot had bought the painting at sale after her brother-in-law’s death. But the scandal of his painting Olympia was raging at the time and she had been afraid that a painting by him wouldn’t have been accepted by the museum. By 1930, the Louvre happily accept it.

Figure 21. Young Woman in front of Window, ‘Summer’ Berthe Morisot, 1880

Figure 22. La Dame Aux Evantails, Edouard Manet, 1873, Musée d’Orsay

One final story, when Ernest Rouart was away fighting during the first World War, Julie visited Monet at Giverny. She wrote to her husband of watching Monet paint his Water Lilies. In 1957, 40 years later, a widowed Julie Manet went to a Paris gallery to purchase a final painting, one she had watched Monet painting.

Julie Manet was born into that rarest of circumstances - a family both financially secure and culturally open. Her mother hadn’t planned to marry, yet neither marrying nor becoming a mother deterred her from pursuing a career as an artist. With Julie, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction. She married young, putting aside whatever ambition she might have had. Her husband, her three sons, (Figure 23) were the center of her life. And yet, her mother was never far from her mind. She fought to have Morisot’s name remembered. Her accomplishments acknowledged. The Musée Marmottan-Monet is proof that she succeeded. This exhibition shows how she achieved it.

Figure 23. Julie Rouart and her sons, Ernest Rouart, 1913, private collection

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please click here or sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.