Joan Mitchell: A Life in the Abstract

Claude Monet - Joan Mitchell, Dialogue" and "Joan Mitchell, Retrospective” Fondation Louis Vuitton

Joan Mitchell on Art & Life

“My paintings repeat a feeling .. it’s more like a poem…that's what I want to paint.”

“My paintings are titled after they are finished. I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me - and remembered feelings of them…”

“Painting is the only art form except still photography which is without time. Music takes time to listen to and ends, writing takes time and ends, movies end, ideas and even sculpture take time. Painting does not...It's a still place…(O)ne word…one image”

“I think love has to do with painting. I don’t paint well out of violence or anger. I don’t like that at all. I don’t want to look at descriptions of horror. I mean, the world is horrible [but] do I want to hang that on the wall?”

“Painting is the opposite of death. It permits one to survive, it also permits one to live.”

“I’m happy when I’m painting. I like it.”

The Joan Mitchell exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton is actually two exhibitions. One is a retrospective organized in conjunction with the Baltimore Museum of Art and the San Francisco MoMA. The other, in conjunction with the Musée Marmottan-Monet, is a Monet-Mitchell dialogue. (Figure 1) I went to the Monet/Mitchell dialogue first since I was leery of becoming Mitchell-sated. As it turns out, the retrospective was short and succinct, the dialogue, long and luxurious. And to be completely honest, it made me appreciate Monet more than ever. Grounded in nature and immersed in abstraction. Cataracts will do that for you, I suppose.

Figure 1. Monet-Mitchell Dialogue, Fondation Louis Vuitton

As the curators noted, the Fondation is one of the few places that such an exhibition could be held. Monet’s late paintings are huge. Many of Mitchell’s paintings here are even larger. Some aren’t single canvases at all. They are triptychs and quadriptychs and polyptychs covering entire walls. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Joan Mitchell Arte.tv To give you an idea of the size of Mitchell’s paintings

Joan Mitchell was born in 1925 in Chicago. Her mother was a poet and the co-editor of a poetry magazine. Her father, a doctor, was an amateur artist. Hers was a childhood filled with literature and art. And sports, in a few of which she excelled - among them, figure skating, swimming and tennis.

Following her graduation from the Art Institute of Chicago, she went to Paris for a year, as the recipient of a travel grant. Back from Paris, she moved to New York where she hung out with the cool guys of abstraction, like Jackson Pollack, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. She held her own with them, which wasn’t easy for a woman painter. One who, unlike Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krasner, and Elaine de Kooning, (married respectively to Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollack and Willem de Kooning), wasn’t married to any of those guys. Those women were known, during their lifetimes and still, as the painting wives of male artists. But not Mitchell. She was taken seriously by those alpha males and by the critics, too. Her paintings hung in their exhibitions.

Mitchell may not have been married to an American all star but her nearly quarter century relationship with the French Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle (Figure 3) was every bit as fraught as marriage to any of them might have been. When their affair began in 1955, he was living in Paris. Where she moved in 1959. Eight years later, with an inheritance from her mother, she bought a two-acre estate overlooking the Seine, in Vétheuil, (Figure 4) just outside of Paris. Where Monet lived before he moved to nearby Giverny.

Figure 3. Joan Mitchell & Jean-Paul Riopelle in Paris, 1963

Figure 4. Joan Mitchell’s home, La Tour, Vétheuil, France

Before Riopelle left Mitchell for a much younger woman in 1979, their relationship, according to one critic, recalled those about which one reads and shakes ones head - such a waste of energy, such a waste of time. Think for example of Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin or Lee Miller and Man Ray or even Mitchell’s contemporaries, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock.

When Riopelle and Mitchell met in the summer of 1955, she was a rising star in the abstract expressionist movement in New York. He was already a successful abstract artist in both Europe and North America.

Peter Schjeldahl, the late art critic for the New Yorker described a dinner party he attended in the 1970s, which Mitchell also attended. Schjeldahl described how Mitchell responded to a woman who announced her upcoming marriage. Mitchell called her “so bourgeois,” forgetting (or perhaps regretting) that she had once been married, too, albeit briefly to Barney Rosset, the founder of Grove Press.

Then Riopolle showed up. He apparently stood on the stairs but she refused to join him and speak quietly with him. Instead she told him exactly what she thought of him, screaming at the top of her lungs. Schjeldahl wrote, “Here was craziness of a scary and rare order. Those who knew Joan Mitchell pass these kinds of stories around like sacred-monster trading cards.”

In the Arte.tv film produced in conjunction with this exhibition there is an interview with Mitchell recorded toward the end of her life. The interviewer asks Mitchell about Riopelle. It’s a legitimate question, they were artists working and living together for nearly 25 years. But Mitchell wasn’t having any of it. She bridled and asked the interviewer if the film was about Riopelle, too. Finally she replied, finding the most self loathing, self deprecating way to describe their relationship, using that most bourgeois of phrases, ‘I was his mistress.’

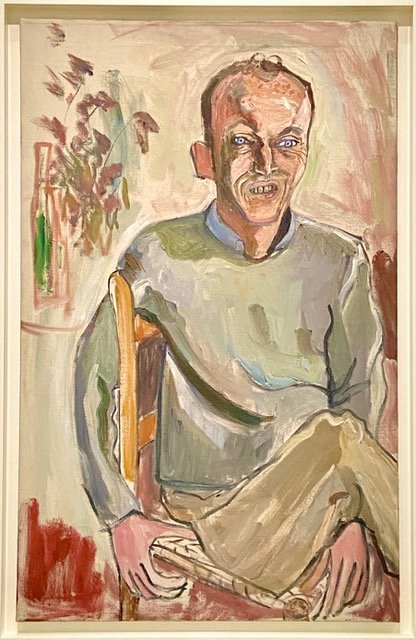

The art historian Linda Nochlin (who sat for her portrait to Alice Neel, Figure 5) interviewed Elaine de Kooning who remembered this incident, "I was talking to Joan Mitchell at a party … when a man came up to us and said, 'What do you women artists think . . .' Joan grabbed my arm and said, 'Elaine, let's get the hell out of here.''

Figure 5. Linda Nochlin and daughter Daisy, Alice Neel, 1973

Here is how one writer explains it, “(Mitchell’s mission) … was to get herself out of situations that threatened her freedom. The situations generally involved fatherly importunity or condescension.” For Mitchell, “The personal wasn't political—she was leery of all solidarities, including the feminist one…”

So, what about her paintings, I hear you asking.(Figure 6) Mitchell said she hated that “people did not know how to look and could only see painting through words” Which is a little annoying for an art historian. Would she have preferred that people quietly or enthusiastically nod their heads or perhaps grunt, in appreciation?

Figure 6. Joan Mitchel, Two Pianos, 1980

Mitchell was deeply influenced by poetry, which had always been a part of her life. as the poetry writing daughter of a poet. Her own home and studio in France were filled with poetry books, which she was always reading. She likened her paintings to poems. Mitchell said, “I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me - and remembered feelings of them …..”

The poet Frank O’Hara, (whose portrait Alice Neel painted twice in 1960, Figure 7) a strong apologist for abstract art, became Mitchell’s friend in the early 1950s. She painted ‘To the Harbormaster’ in 1957, (Figure 8) after one of his poems. In 1970, she titled another painting ‘Ode to Joy,’ after another of them, (Figure 9) this time in his memory. He died in a car accident in 1966. He was only 40 years old.

Figure 7. Frank O’Hara, Alice Neel, 1960

Figure 8. To the Harbormaster, Joan Mitchell, 1957 (after a poem by Frank O’Hara)

Figure 9. Ode to Joy, Joan Mitchell, in memory of Frank O’Hara, 1970

Mitchell admitted to the influence of two artists - van Gogh and Cézanne. She said, “Sunflowers are something I feel very intensely. They look so wonderful when young and they are so very moving when they are dying. I don't like fields of sunflowers. I like them alone or, of course, painted by Van Gogh.” (Figure 10)

Figure 10. Sunflowers, Vincent Van Gogh

Patches of yellow appear in many of her paintings, but as she reminded one interviewer, “there is sadness in the sunshine just as there is joy in the rain, yellow is not always happy.” (Figure 11)

Figure 11. Minnesota, Joan Mitchell, 1980

As for Cezanne, Mitchell, like so many of us, was drawn to his Mont Sainte-Victoire paintings. An anchor in his life, just as the view from her studio in Vetheuil was the anchors of hers. And Monet’s garden at Giverny was the anchor of his.

Mitchell denied being influenced by Monet. To put that statement into perspective, Monet denied being influenced by Turner. But the similarities are there whether Mitchell acknowledged them or not. That is what this exhibition explores.

Mitchell once said, “What excites me is what one color does to another and what they both do in terms of space and interaction.” She did not create illusionist space, she juxtaposed colors on the canvas, for the observer’s eyes to blend. Which was what Monet did. Which was what Seurat and his fellow Pointillists did.

For Monet, late in life and Mitchell, too, “color was a world unto itself rather than a window into the world.” At Giverny, Monet was both a painter and a horticulturalist. (Figure 12) And according to one critic, in the paintings she composed at Vetheuil, Mitchell “treat(ed) her favorite colors the way a gardener plants a flower bed, combining them closely together or piling them top of each other in order to enhance their discordant brilliance or vibrant darkness.” (Figures 13, 14)

Figure 12, Le Bassin aux Nymphéas, Claude Monet, 1918-19

Figure 13. Fragments of a Landscape, Joan Mitchell

Figure 14. La Grande Vallée, Joan Mitchell, 1983

Monet suffered from losses at the end of his life - the death of his wife and his son, a series of health problems. But he kept painting. He needed to keep painting. The last decade of Mitchell’s life was filled with so many losses, even Job might not have survived. But she kept painting, too. Her long time lover, Riopelle left her in 1979, two years later Edrita Fried, her long time therapist died (Figure 15) and two years after that, so did her sister, from cancer. Her own health problems began the following year. An operation for jaw cancer in 1984, a hip operation five years later. All the while suffering from undiagnosed lung cancer to which she succumbed in 1992, at the age of 67.

When one critic asked Joan Mitchell how she managed to keep painting her huge canvases, as sick as she was. She said, “I just got up on that fucking ladder and told myself, ‘This stroke has to work.” (Figure 16) The philosopher Yves Michaud wrote in 1992 that Mitchell’s paintings included only ‘the essentials … bouquets of colors and sensations, musical chords, a fleeting feeling of exultation or a .. veil of rain and sorrow.” As another critic put it, there is a joie de vivre in her paintings that Mitchell did not experience in her life. (Figure 17). That Monet also expressed in his paintings, too. (Figures 18, 19)

Figure 15. Edrita Fried, Joan Mitchell, 1981

Figure 16. River II, Joan Mitchell, 1986

Figure 17. Mon paysage, Joan Mitchell, 1967

Figure 18. The Artist’s House from his Rose Garden, Claude Monet, 1922-24

Figure 19. La Grande Vallée, XVI, Joan Mitchell, 1983

Copyright © 2022 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.