It’s a Wrap: Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Christo & Jeanne-Claude at the Pompidou

Figure 1 Exhibition poster for Christo & Jeanne Claude

Last week we talked about Jeff Koons who is not everyone’s idea of the ideal artist. Not enough suffering, too much success. And how can that stuff be called art anyhow, blah, blah, blah. As I pondered the topic of this week’s discussion, I was immediately seized with the thought that there are probably as many people who reject the idea that rapping is music as reject the idea that wrapping is art. But I contend that as with any subject, even if, perhaps especially if, you don’t like it or understand it, it is worth spending at least a few minutes trying to learn something about it.

I will begin with rapping. I made a deal some years ago with my now 26 year old son. If he accompanies me to the symphony, I will listen to rap music with him. Of course the songs he shares with me are carefully curated and the lyrics that everyone complains about with rap are not on the play lists he has prepared for me. But I have to admit I find it more than a little ironic that the same people who complain about the misogyny of rap music wax enthusiastic about paintings that celebrate and simultaneously condemn the female form, as for example, the trope of a young, naked woman gazing at a mirror. (Figure 2) This Vanitas reminds the young woman that beauty and youth are fleeting. But she is standing there, nude, for the male gaze, not her own pleasure. And to chastise her for displaying her only value, her only currency in a misogynistic patriarchy doesn’t seem any better than the misogynistic rap lyrics condemned by devotees of classical Western painting and classical Western music.

Figure 2. Vanitas, the Mirror, Leon Bazille Perrault, 1886

Chance the Rapper, (have you heard of him?), has a rap I especially like called ‘Sunday Candy’ (Figure 3) which celebrates his grandmother this way: “She can say in her voice, in her way that she love me With her eyes, with her smile, with her belt, with her hands, with her money I am the thesis of her prayers…” The hook (chorus), sung by a woman, compares herself to the holy wafer of communion and tells Chance how to make love to her, “You gotta move it slowly, Take and eat my body like it's holy. I've been waiting for you for the whole week, I've been praying for you, you're my Sunday candy.” The only thing I feel a little bad about is that nobody has told rappers that free verse is okay, they don’t have to work so hard to rhyme. Never mind, call me old fashion, but I like rhyming. If you are feeling nostalgic for the good old days, listen to this video of Chance the Rapper singing Sunday Candy at the Obamas’ final Christmas party, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qv6vvDV7MCo

Figure 3. Chance the Rapper singing Sunday Candy, 2015

Okay, that’s settled, rapping IS music. Now on to wrapping. And to show how wrapping is art we will take ourselves to the exhibition currently on at the Pompidou entitled, ‘Christo et Jeanne-Claude Paris!’ And as part of our discussion about wrapping, we will talk about ephemeral art, performance art and installation art. But why stop there ? We’ll also talk about collaborative art, political art and finally, the unique way in which Christo and Jeanne-Claude financed their art.

Let’s start with the ephemeral. I am a big fan of ephemeral art in all of its manifestations, from fireworks to world fairs, from victory parades to funeral processions, from celebrations of approbation to demonstrations of dissent. You will not be surprised to learn that one of my areas of expertise is the way in which temporary displays are used to ‘try out’ ideas before they go permanent. Daniel Burnham’s 1909 City Plan of Chicago applied lessons learned from the wildly successful Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. And sometimes temporary structures at world fairs are so beloved that they aren’t dismantled at the end of the run, like the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco and the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

The exhibition at the Pompidou is in two parts, the first part considers Christo’s early works, from when he arrived in Paris in 1958 through 1964, when he and Jeanne-Claude (his wife and partner) moved permanently to New York. The second part of the exhibition focuses on the wrapping of the Pont Neuf. It begins with the film ‘Christo In Paris,’ by the documentary film making brothers David and Albert Maysles. This delightful film follows Christo and Jeanne-Claude through every step of their quest to gain permission to wrap the Pont Neuf. It took them 10 years, mostly spent talking with politicians and Parisians, trying to convince them of the merit of their project. Part 2 of this second part shows the preparation for and realization of the wrapping of Pont Neuf itself, and includes sketches and drawings by Christo, photographs by Wolfgang Volz, a moquette of the project and surviving bits of metal and fabric from the installation.

The exhibition begins with a portrait of a beautiful woman. (Figure 4) Which is a little disconcerting since this is an exhibition about the Wrapper King. Who painted this portrait and who is portrayed ? Turns out that Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, born in 1935, into a prominent family in Gabrovo, Bulgaria was a classically trained artist. His father, a chemist, owned a textile factory. Christo studied drawing as a child and art at the Fine Arts Academy in Sofia, where his mother was a secretary. One of Christo’s first jobs in Bulgaria after he graduated from art school was to prove useful for his future career. He was sent by the communist government to show farmers along the route of the Orient Express how to arrange their haystacks and machinery to suggest activity and prosperity. So that people looking out the window of that speeding train would see that everything was great, that everyone was fine.

Figure 4. Précilda de Guillebon, Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, 1958

According to William Grimes, (NYT, May 31, 2020) this experience taught Christo how to work in open spaces and how to deal with all kinds of people. Which is true, which he did. But I think that Christo learned another lesson, too, that you can camouflage reality, that you can change it, enhance it. That you can make buildings, for example, appear different. History is full of military and civilian rulers, I’m thinking Hitler and Mussolini here, but there were many others before them, who used art and artifice to camouflage reality. Like maquillage (makeup), as long as the parade keeps moving along, or the train keeps rolling by, nobody needs to know that displays of prosperity actually hide poverty, that buildings are made of plaster and cast, not concrete. That life is a stage set.

Christo was studying and working in Prague in 1956 when Soviet forces crushed the Hungarian uprising. Seeing no future for himself in Eastern Europe, he escaped to Vienna where he stayed long enough to complete a semester at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. Next stop was Geneva, then finally Paris, in 1958. He supported himself washing dishes and painting portraits. One of the portraits he painted was of Jeanne-Claude’s mother, Précilda de Guillebon, which is how he met his future wife. Seems as if Jeanne-Claude’s mother, who was accustomed to helping young people, was very much taken with the young skinny refuge artist who could barely speak French. She found him a place to stay, a chambre de bonne.

He may have been painting portraits of high society women to survive, but Christo had already started wrapping. He was wrapping small cylindrical metal cans and bottles, with fabric stiffened with lacquer and tied with string. (Figures 5 & 6) One evening after dinner, he invited the debutante daughter of his benefactress to his room to see his work. A fifth floor (maybe higher) walkup with some hall lights that didn’t work or didn’t work long enough to get to the next landing and the next light switch. As Jeanne-Claude describes it in the documentary, after walking all the way up those many flights of stairs, sometimes in the dark, he opened the door to his room and just before the hall light went off for the umpteenth time, she saw a labyrinth of wrapped stacked whatevers everywhere. She wondered if she was going to make it out of that apartment alive.

Figure 5. Wrapped Cans,

Christo, 1950-60

Figure 6. Wrapped Package,

Christo, 1961

But they soon became inseparable and she soon took on the role of collaborator and assistant for his large scale projects. At the same time as Christo's first gallery exhibition in Cologne in 1961, he and Jeanne-Claude created their first temporary outdoor environmental works of art, Dockside Packages and Stacked Oil Barrels. For the first, the artists covered large rolls of industrial paper with tarpaulins which they secured with ropes. For the latter, using cranes and other machinery, they stacked a large number of oil drums. In what would become their modus operandi, they sought and received permission from the Port Authority and they found volunteers to help them, the dockworkers, who also lent them all the materials. The temporary work of art remained for two weeks. The only element missing was the financing that would become part of their later, more ambitious works.

Their next temporary piece was constructed in Paris and was Christo’s response to the construction of the Berlin Wall in October 1961. He built a wall of barrels to barricade rue Visconti, one of the narrowest streets in Paris. He didn’t wrap the barrels, he didn’t paint them, he just stacked them the night of June 27, 1962. It was his own Iron Curtain to protest the building of that other Iron Curtain. (Figure 7) He had a permit but the the police made him dismantle his temporary structure a few hours later.

Figure 7 Wall of Barrels, or Iron Curtain, rue Visconti, Paris, Christo, 1962

Christo was still wrapping small, but his wrappings changed. He began to partially reveal what had been concealed, bottles and cans still, but also now tables and chairs. (Figure 8)

Figure 10. Sketch of and realization of Store Front (Taschen), Christo, 1960s

Christo was not the first wrapper, he was preceded by the surrealist Man Ray who, in 1920, in homage to a poem by Isidore Ducasse, had wrapped a sewing-machine in a blanket and bound it with string. (Figure 9)

Figure 9. A sewing-machine in a blanket bound with string, Man Ray 1920

Christo also began to play around with the idea of concealing in another way. He made store fronts and found glass cases, and subverted their function by concealing rather than displaying. (Figure 10) To differentiate his wrapped pieces from his society portraits, Christo signed his wrapped pieces ‘Christo’ and used his surname to sign his portraits.

Figure 10. Sketch of and realization of Store Front (Taschen), Christo, 1960s

In the late 1950s, early 1960s, Christo’s and Jeanne-Claude’s personal lives were a little messy. (Figures 11 & 12) Jeanne-Claude, a very attractive, very wealthy debutante, was courted by many very eligible bachelors. She became engaged to one of them. She was in love with Christo. She went ahead with the marriage to please her parents. But she was already pregnant with her and Christo’s child. She went on her honeymoon with her new husband and when it was over, she left him and moved in with Christo.There was a lot of drama, her parents insisted that she leave Christo, she wouldn’t, and she didn’t speak with them for over two years. For a while she lived alone with their son. As Jeanne-Claude put it, her parents were happy to have Christo as a son, they just didn’t want him as a son-in-law. Finally it all got sorted out and the young family left for New York in 1964.

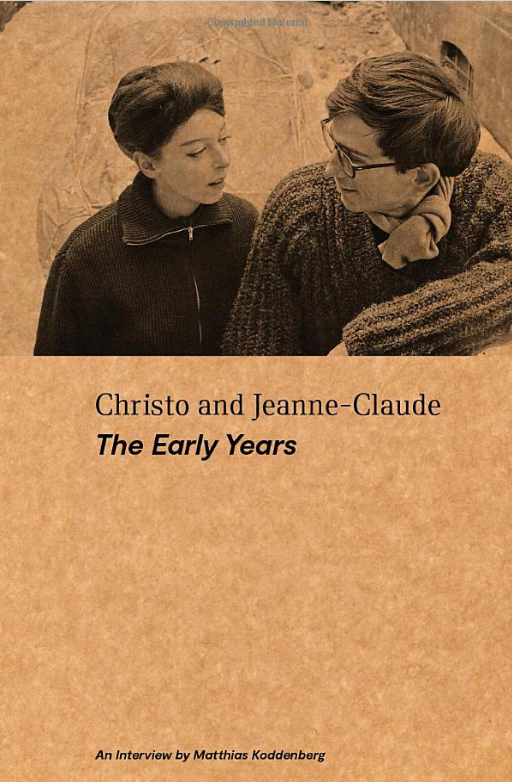

Figure 11. Christo and Jeanne-Claude, photograph

Figure 12. Green Store Front, photograph of Christo

& Jeanne-Claude, 1964

The second part of the two part exhibition as I mentioned above, is the wrapping of Pont Neuf, a project that began in 1975 and came to fruition a decade later. (Figures 13, 14, 15) The full length documentary film by the Maysles brothers is enchanting and absorbing, cutting between conversations / interviews with Christo and Jeanne-Claude, their meetings with government officials and private citizens interspersed with scenes of everyday life in Paris focused in and around the Pont Neuf, the city’s oldest bridge. Christo talks about how important the process of seeking government permission and citizen approval is for his work. To Christo, these discussions, these debates were as much a part of the collaborative process as the actual wrapping itself. He delighted in the environmental impact studies and protests, the town hall meetings and random encounters. He saw it as a celebration of democracy, of citizen participation.

Figure 13. Pont Neuf wrapped, Christo

& Jeanne-Claude, 1985

Figure 14. Pont Neuf wrapped, detail. Christo

& Jeanne-Claude, 1985

Figure 15. Pont Neuf sketches

& drawings, Christo, 1975-85

For him, it was important, it was essential. The performance art aspect of any of Christo’s and Jeanne-Claude’s wrappings can be seen to include a myriad of moments, from Christo’s speaking at town hall meetings, to the workmen unleashing the fabric to descend along the facade of the Reichstag (Figure 16) to the debate amongst strangers about whether or not wrapping was art, to all of the people who walked on the wrapped pedestrian walkway of the Pont Neuf (Figure 17) or walked under the gates in Central Park. (Figure 18)

Figure 16. Workman posed to unwrap the wrapping, Reichstag, Berlin,

Christo & Jeanne-Claude

Figure 17. People on the wrapped Pont Neuf, Paris 1985, Christo & Jeanne-Claude.

Figure 18. People under the Gate

s, Central Park, NYC, 2005,

C

hristo & Jeanne-Claude

One of the most amazing things about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s art is how they financed their work. They never accepted dona-tions or contributions. They were self sustaining artists. Christo’s sketches were their currency. He produced them, they sold them or held onto them and used them as collateral for the money they borrowed from banks, and only from banks because as Jeanne-Claude says in the documentary, banks pay on time, foundations don’t. And once a project got started, they had payrolls to meet and they didn’t want to keep their employees waiting. Their entrepreneurial approach to financing was so impressive that it was developed into a case study for MBA students at Harvard Business School.

A few things I should mention before closing. The couple worked on their projects together, with two exceptions, only Christo drew and sketched and according to her, only Jeanne-Claude met with their accountant ! Because they thought it would be easier to get bank loans, only Christo’s name was initially attached to their collaboration. But by 1994, they were well enough known that they began using both of their names, and did so retroactively. During the 50 years they worked together, until Jeanne-Claude’s untimely death in 2009, they completed 22 projects, another 37 were never completed. Yes, they sold Christo’s sketches and drawings to pay for their wrappings but nobody owned their wrapping. They were too big and too ephemeral to be owned. And they were free, the buildings and spaces they wrapped did not pay to be wrapped and the people who experienced those wrapped spaces and buildings did not pay to do so. When asked why they wrapped, Christo (or maybe it was Jeanne-Claude) responded that it gave them pleasure. They noted that a painter isn’t asked why s/he chooses to paint what s/he paints. They were moved by something or someplace and that was enough. They said they had no agenda, but in at least one instance, Christo did.

Over the River was a proposal to suspend a silver canopy over 42 miles of the Arkansas River. (Figure 19) Christo and Jeanne-Claude spent years in state and federal courts before Christo called off the project in 2017 to protest Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States. Christo told the New York Times “I came from a communist country, I use my own money and my own work and my own plans because I like to be totally free. And here the federal government own(s) the land. I can’t do a project that benefits this landlord.”

Figure 19. Photo of Christo and their Over the River, Arkansas River project, withdrawn, 1917

As with Jeff Koons, many art critics and artists do not concede that what Christo and Jeanne-Claude did was art. Some argued that it was banal and meaningless others argued that it was pretty and too easily pleasing to too many people. But if you think of their wrapping as draping, then there is a history, a context and a beauty that is undeniable. A recent exhibition at the Musee des Beaux Arts in Lyon included Christo in a temporary exhibition on drapery. Mostly about the drapery used to conceal and reveal the human form, the sensuality and elegance and fluidity that define the drapery on a classical statue or a Renaissance one can equally be applied to the way in which the fabric follows the curves and volumes of a building wrapped / draped by Christo, see figure 14 above. (Figures 20, 21)

Figure 20. Nike of Samothrace, detail

of conceal/reveal drapery.

Louvre, Paris

Figure 21. Pieta, Michelangelo uses drapery to increase the size of the

Virgin’s body so that it looks normal

for a grown man to be lying across

the lap of a woman

Try to see any of the documentary films that the Maylses brothers made about Christo (this is the same team that made Grey Gardens, the film about the hoarding mother and daughter duo, relatives of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis). Christo and Jeanne-Claude began dreaming about wrapping the Arc de Triomphe in 1961. It was scheduled to happen in conjunction with this exhibition, but the exhibition was delayed and the wrapping was too, because of the pandemic.

In the meantime Christo has died (May 2020) but the wrapping is still scheduled for next fall, 60 years after it was first conceived, as a memorial to them both.(Figure 22)

Figure 22. Arc de Triomphe project, Christo & Jeanne-Claude Sept. /Oct. 2021

Jeanne-Claude described their wrappings like a pregnancy. Sometimes you are sick for two months, sometimes not at all, but once the child is born, all that is forgotten and you are a parent. When I think of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s ‘wrappings’ I think of summer vacations: preparing for them, experiencing them, reminiscing about them afterwards. And I have my fingers crossed that you will be able to move beyond the planning stage for your next trip to France soon, maybe even planning it for next fall, in conjunction with what I am guessing will be Christo’s and Jeanne-Claude’s final wrapping. Finally, when I think about their wrappings, I think about looking at old things, familiar things, things that I haven’t paid much or any attention to, through new eyes, through a different lens. Their art is the joyful, thoughtful and intentionally temporary ‘dressing’ of natural and man-made monuments. What they created was a pure, transitory experience. What could be better?

Copyright © 2020 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved