The Master of the Strung-out Figure

Fondation Giacometti Institut

Figure 1. Fondation Giacometti Institut

I went to a museum, finally, after 2 1/2 brutal months, 10 brutal weeks, without museums. You know, like without a drink for some people, without a smoke for far fewer. Yes indeed I am addicted to museums in Paris, indeed anywhere, actually. Ask me what I did in Honolulu, on Bali, in Hong Kong. Never mind. Paris. Museums. The first re-opening announcement email I received was from the Institut Giacometti. Have you heard of it ? Maybe not. It is in the 14th, not far from Montparnasse. The museum opened in 2018. That same year there was a really comprehensive retrospective of Giacometti’s sculptures at the Musee Maillol (I’ll write about that one soon, promise). So, I put going to the Giacometti Institut on the back burner, feeling fairly Giacometti’d out at the time. But with no competition, there was no way I was going to wait a moment longer to visit this museum.

This was not a casual outing. Equipped with mask and gloves, I risked my life dear reader to make my life worth living. I boarded a metro, masks obligatory. The car was virtually empty. And thank goodness for that because only every other seat is available to sit on, re: social distancing. I got as close as I could to my destination. About 60 metro stops are currently closed, including the one I usually take, Jasmin, right in front of the apartment building where Jacqueline Bouvier lived during her junior year of college. The metro at my destination was also closed. Never mind, I got there. Do not go without a timed ticket, purchased online. As I flashed my ticket at the guard, several people were turned away at the door, they had no pre-purchased ticket in hand.

The museum is in a beautifully preserved Art Deco building, in the former studio of an interior designer. (Figure 2) At the entry, after your ticket is scanned, the guard watches you spritz your ever more chapped hands with the now obligatory hydroalcoholic hand cleanser. Then, turning right and down a few steps below the Rez-de-chaussée, (ground level) is a recreation of Giacometti’s studio, replete with the single bed upon which he awaited inspiration, or maybe welcomed guests, whatever.(Figure 3)

Figure 3. Giacometti’s studio/atelier reconstruction

It reminded me of the recreation of the sculptor Brancusi’s studio in front of the Centre Pompidou in the Marais or the actual home of Georgio Morandi in Bologna, Italy. As I walked around this rather small, quite intimate museum, I marveled at how well the architect had managed to create something new without destroying the exquisite Art Deco shell and details. Later I read that this had been the architect, Pascal Grasso’s goal. He wanted to create a museum that simultaneously celebrated what was already there while ‘devising a contemporary space endowed with its own identity.’ I was particularly impressed by the ceiling light fixture and so I was pleased to read that, ‘(t)he form of the suspended lights was inspired by the geometry of the historic ceilings that accommodate them.…” (Figure 4) Well, I got it, so obviously he succeeded. And it reminded me of an exhibition at the Picasso Museum that I saw a couple years ago on the furniture and lighting designs of Diego Giacometti, Alberto’s younger brother. The exhibition focused on his work at the Picasso Museum, especially how harmoniously his furniture and lighting fixtures accommodated the 17th century hotel particulier, Hôtel Salé which is home to the Picasso Museum. Perhaps Diego was Grasso’s inspiration.

Figure 4. Pascal Grasso, Fondation Giacometti Institut, renovation architect, 2018, Lighting

While you might think that an interior decorator’s former studio and home is an odd choice for a sculptor famous for his strung out figures, actually it is a perfect fit since Giacometti, working with Diego (his junior by 13 months), started creating decorative objects in his late 20s, initially for financial reasons but subsequently because they were really good at it. The connection between his ‘high art’ and his ‘decorative art’ remained a constant throughout his career. Working with the interior designer, Jean-Michel Frank in the 1930s, Giacometti created pieces for clients all over the world, Giacometti concentrated on lighting but he also designed small objects and furniture.(Figure 5, Figure 6) In 1948, Giacometti wrote that “…objects interest me hardly any less than sculpture, and there is a point at which the two touch.”

Figure 5. Alberto Giacometti for interior designer Jean Michel Frank, 1935

Figure 6. Alberto Giacometti, lamp, 1933

In the recreated atelier, there are reproductions of Giacometti’s iconic figures. In poking around the museum’s website, I learned about the role that brothels played in Giacometti’s life and art. Like Toulouse-Latrec at the end of the previous century, Giacometti frequented brothels, frequently. He was obsessed with prostitutes. Unlike TL though, who developed friendships with the prostitutes, Giacometti seems to have been mainly obsessed with looking at them, having sex with them, making art of them. He once described a group of prostitutes he saw in a café in northern Paris, as having ‘strange, long, thin and tapering legs,’ a phrase that could just as easily apply to his strung out sculptures. One of the brothels he particularly liked was called Le Sphinx, (Figure 7) where having sex with the prostitutes wasn’t obligatory as long as you bought enough drinks at the bar. Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre hung out there. In 1950, Giacometti identified his ‘Four Figurines on a Pedestal’ (Figure 8) as ‘several naked women seen at the Sphinx’. By 1950, French brothels were only a memory. A former prostitute had successfully petitioned the French government to close them all in 1946. Giacometti wrote that for him, the forced closure of Le Sphinx was ‘intolerable’. By then he had married a woman who would become his model and whose devotion to him continued after his death and resulted in this lovely museum.

Figure 7. Alberto Giacometti, At the Sphinx, 1950

Figure 8. Alberto Giacometti. Four Women on a Pedestal, 1950

Although the museum is small, there’s lots to see. I wandered into a room to the left of the library, which might more accurately be described as a wall of books, but one which you cannot get close enough to read the books’ titles. (Figure 9) In the room off the book wall, and without any identification that I could find, were two huge doors embellished with bas relief designs. (Figure 10) They were so large they reminded me of Rodin’s Gates of Paradise, a stripped down version to be sure, but still, huge. I asked a young woman, maintaining appropriate social distancing, while masked, if she could tell me more about the doors. She said that they had been created for an American industrialist. I asked if she could remember who. She said somebody named Kaufmann. I asked if it might be Edgar Kaufmann. She said yes, that sounded right. I asked her if she knew what they were for and she said that it was for a mortuary monument; that the doors at the museum were one of only two versions, the other was in the U.S. Well, of course I know Edgar Kaufmann, the owner of the eponymous department store in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania who had commissioned the architect Frank Lloyd Wright to design what is one of Wright’s best known buildings, Kaufmann’s weekend home in Fallingwater, Pennsylvania, which is now on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. I had to dig to find out about the crypt. This is what I learned. On the evening of September 7, 1952, Edgar Kaufmann and his wife, Liliane, were spending a weekend at Fallingwater, Liliane Kaufmann either intentionally overdosed or accidentally took too many sleeping pills. Pulling a Chappaquiddick, Edgar Kaufmann didn’t exactly go to sleep then call his lawyer, as Teddy Kennedy was to do several years later. Instead, he drove his wife back to Pittsburgh, a 2 1/2 hour drive rather than take her to the local hospital to have her stomach pumped. Would she have lived if she had had immediate treatment, who knows, but two years later, Edgar married his nurse, who was half his age. Conveniently for the nurse, Edgar Kaufmann was dead a few months later.

Figure 9. Fondation Giacometti Institut, Library

Figure 10. Alberto Giacometti for Kaufmann Crypt, 1956

Alberto Giacometti for Kaufmann Crypt, 1956

So, what about the crypt I hear you murmuring impatiently. Apparently sometime after his parents’ deaths, Edgar Kaufmann Jr. had their bodies exhumed from a Pittsburgh cemetery and reinterred in a crypt he had built upriver from Falling-water. So, where exactly IS the crypt ? (Figure 11) It is hidden by rhododendron and mountain laurel, across a small, seldom used footbridge over a tiny creek. Although nearly 140 000 visitors pass within 100 yards of the crypt annually, but no one visits it because no one knows it is there. (NYTimes Magazine 2001). That’s what happens when you’re not part of the official tour, remember that. It was Jr. who commissioned Giacometti to create the crypt's immense bronze doors in 1956. The bas-relief depicts two solitary sticklike figures, a woman sitting against a tree on the right and a man standing far away on the left, facing each other across a barren valley. Not exactly serene but based upon what we know about Edgar Kaufmann’s philandering, it is not surprising either. No, Edgar, Jr. is not buried with them. His own ashes were scattered around the grounds of Fallingwater. I hope I have whetted your appetite to see these doors - either at Fallingwater or in the Giacometti Institut. Or both. And I guess this means that I will have to make a third pilgrimage (not bragging) to Fallingwater if I want to see the doors in situ.

Figure 11. Alberto Giacometti, Kaufmann Crypt, Fallingwater, Pa. 1956

The museum’s current temporary exhibition, entitled ‘In Search of Lost Works’ (Figure 12) uses sketches, letters and photographs to reconstruct the lost or destroyed works from Giacometti’s earliest years and display them alongside works which survive from the period. Beginning in 1925, Giacometti’s trajectory is traced from his student years at Antoine Bourdelle’s Académie de la Grande Chaumière, (Figure 13) through his Cubist years after he denounced representation for simplification and abstraction to the symbolic works he created when he embraced Surrealism. (Figure 14) In later years, Giacometti presented himself as a tortured artist, perpetually dissatisfied with his work, who willfully destroyed it so he could start again. But actually, most of the pieces that did not survive from this early period were just too delicate or only the work of a little-known artist, one who did not yet merit the attention required to preserve them. Whether this exhibition is on or not when you are next in Paris, put this little museum on your list, you’re going to like it here. (Figure 15, Figure 16)

Figure 12. Exhibition poster, Fondation Giacometti Institut

Figure 13. Alberto Giacometti. Self portait bust, 1925

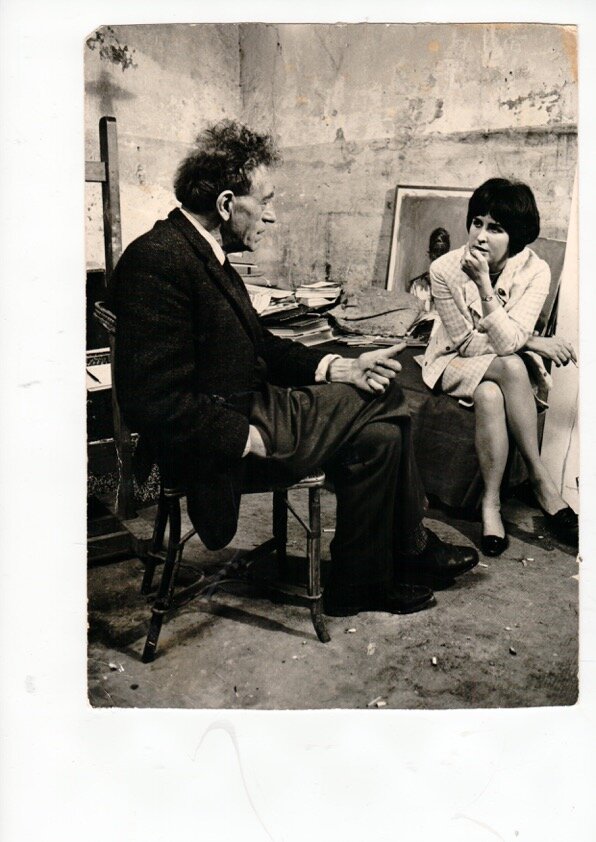

Figure 15. Photo of Giacometti with our Betty

Figure 16. Photo of Giacometti with Rodin’s Burghers of Calais