"If you can eat it, it's not art”

"Marcel Proust. La fabrique de l’œuvre" ("Marcel Proust. The making of the work”), Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF)

Welcome to this, my review of the last of the temporary exhibitions celebrating the life, literature and legacy of Marcel Proust. Surely he couldn’t have known that starving himself to death at age 51 would be good for prolonged celebrations of his life and his life’s work. But it has been.

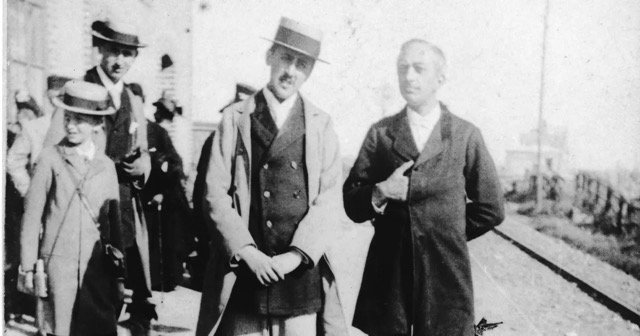

The exhibition that I saw most recently is on through January at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF). One might think that an exhibition at a library would be stuffy. Filled with case after case of fragile manuscripts and old books barely visible in the dimmed light. But that would be wrong. And perhaps because of people’s expectations of stodgy dullness, the library curators worked hard to create a series of visually exciting spaces. (Figures 1a, 1b) The manuscripts are contextualized with canvases (Boldini, Tissot, Manet, Turner, Renoir, etc) and costumes (Fortuny & Doucet) (Figures 2a, 2b), maps and machines (telephone, cinema, automobile, airplane). (Figures 3a, 3b, 3c) And lots of photographs. Of Proust with his father in Venice (Figure 4) and Proust with his friends on the beach, etc. (Figure 5)

Figure 1a. Proust exhibition, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Figure 1b. Proust exhibition, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Figure 2a. Fortuny Gown, Mme Swann, detail

Figure 2b. Ducet Coat, Comtesse de Greffulhe

Figure 3a. Kaleidoscope

Figure 3b Proust with Cinematographe

Figure 3c. Cinematographe

Figure 4. Proust & his Father, Venice, photograph, 1900

Figure 5. Proust & his friends in Cabourg, Normandie, 1907

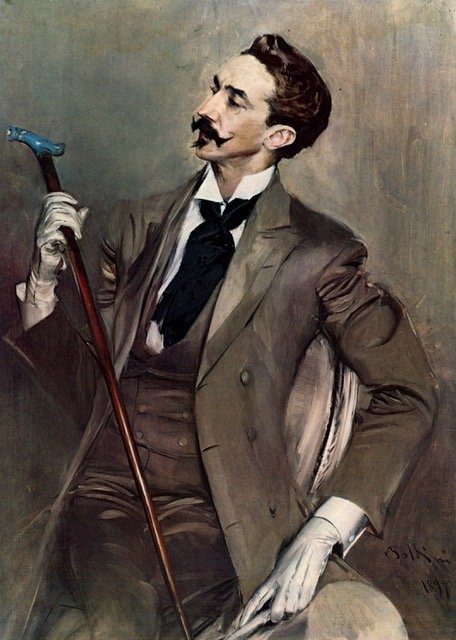

I knew the paintings and had seen some of them at exhibitions this year, like the one at the Petit Palais on Giovanni Boldini (Figure 6), called ‘Pleasures and Days,’ after Proust’s book of the same name. And Tissot’s ‘The Circle of the Rue Royal’ (Figure 7) at the Proust exhibitions at Carnavalet and the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme. Both portraits of men who played prominent roles in Proust’s life and literature.

Figure 6. Comte Robert de Montesquiou, Giovanni Boldini, 1897

Figure 7. The Circle of the Rue Royal, James Tissot, 1868

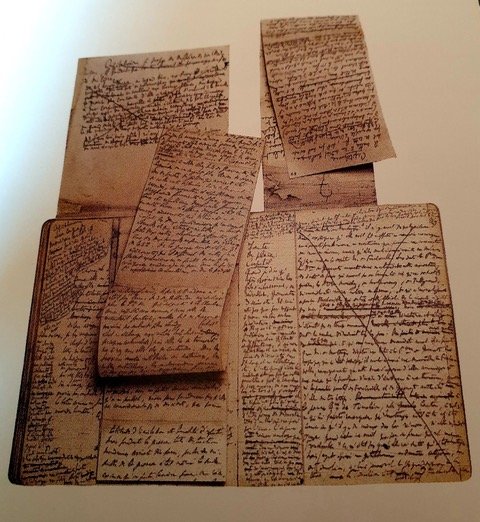

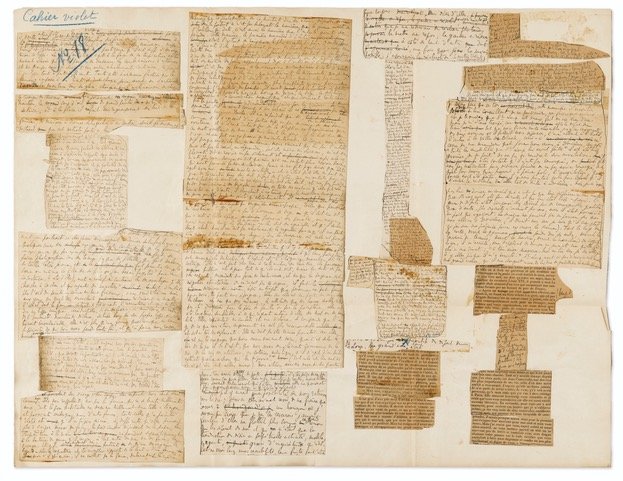

Proust was a hoarder. He would definitely not have used a paper shredder if he had been given one for Christmas. At his death, his brother Robert inherited everything which he passed on to his daughter who donated all of his manuscripts to the BnF. From school essays to multiple drafts of his seven volume opus. Of this opus, there are handwritten manuscripts upon which handwritten corrections on tiny slips of paper are affixed like flaps, to the left of the main text, to the right of the main text, on top of the main text. Corrections of corrections, paper pasted upon paper, like fluttering curlicues. According to curator Nathalie Mauriac, “There is something disproportionate in the scope of Proust’s work, … starting with the famous paperoles, those accordions of fragments of paper folded and pasted into his notebooks.” (Figures 8a, 8b, 8c) Antoine Compagnon, another of the curators offers a tip to understanding Proust’s extensive paper trail. “When Proust crosses out a passage, that does not mean that he wishes to withdraw it but to move it. When he no longer wants it he writes by hand ”deleted.”

Figure 8a. Proust Manuscripts

Figure 8b. Proust Manuscripts

Figure 8c. Proust Manuscripts

All that paper, all those changes, I recognize that. I used to quip that if personal computers had not been invented, I would still be writing (and rewriting) my dissertation. Back ‘in the day’ I began in long hand, on yellow legal pads. And then I typed what I had written. And then I began the ritual of cutting and pasting, crossing out and adding to, draft after draft. And the thing about writing and typing on paper is that changes don’t disappear. You can keep them and refer back to them and even use them. Evidence of what went before remains as long as you have room enough to store them. My response to seeing all that paper in this Proust exhibition was visceral, I was in my carrel, in the Art History Department Library, trying to tame a text.

There are authors who still write in longhand. Like Robert Caro, L.B.J’s biographer. It has taken Caro longer to write about LBJ’s life than it took LBJ to live it. According to Caro fan O.C. Marsden, Caro’s handwritten drafts are “corrected, refined, edited, reworded, disassembled, reassembled, scrapped, rewritten, (and) read out” He could have been describing Proust. I don’t know if Caro has saved any of the paroles, paragraphs and pages that he or his editor Robert Gottlieb (their relationship is the subject of a new documentary by Gottlieb’s daughter) cut during the writing process.

One thing I can tell you is that if Proust hadn’t written his text by hand and if he hadn’t saved all of those bits and slips of paper on which he wrote and rewrote his drafts, we wouldn’t know that his famous madeleine moment began as a piece of stale bread moment and became a dry biscuit moment before it became a madeleine moment. It reveals a truth - that memory is as much made as it is lived.

You know what I mean by Proust’s madeleine moment, right? When the adult narrator, lamenting that he cannot recall his childhood (except his disappointment with either the brevity or absence of his mother’s nighttime kisses), dips a morsel of the madeleine he is eating into the cup of tilleul tea he is drinking. And voila, the memory of his childhood at his Aunt Leonie’s home in Cambray comes flooding into his consciousness. Psychologist Gayil Nalls writes this about the madeleine that wasn’t, ‘the emblematic confectionary that has dominated olfactory literature for decades’ was a literary device. “(I)n the repeated process of memory reconsolidating, a new memory was literally rewritten.” Memory remembered vs Memory created. (a good argument for wondering if Woody Allen is guilty of anything worse than grossly inappropriate behavior with his now wife of 25 years).

My gateway to Proust was asparagus. Specifically two paintings by Edouard Manet, one a bunch, the other, a solitary spear. (Figures 9, 10) Both canvases have been making the rounds since the first Proust exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet last year. They led me to a book called Paintings in Proust by Eric Karpeles, who relates a story I already knew. Edouard Manet painted a bunch of asparagus. The wealthy art collector who purchased the painting, gave the artist 200 francs extra. The next day, the painter sent the patron a painting of a single asparagus spear, with a note explaining that it had slipped from the bunch. The patron was Charles Ephrussi, who, with his uncle, Charles Haas, was the model for Charles Swann in Proust’s novel.

Figure 9. Asparagus, Edouard Manet

Figure 10. Single Asparagus, Edouard Manet

From this asparagus anecdote, Karpeles tells us, “Proust fashioned a tiny morality play …that involved a painting of asparagus, by Elstir” (Proust’s fictional artist). The Duc de Guermantes, in his ‘sumptuous dining room, eating asparagus’ is indignant that Swann has suggested he buy Elstir’s painting of asparagus. The duke considers the price outrageous. “Three hundred francs for a bundle of asparagus! A louis, that’s as much as they’re worth, even early in the season.” Did he really confuse the price of fresh asparagus with the price of a painting? What a boor. As Karpeles notes, Proust transformed a charming celebration of the generosity of an artist and his patron into a tale of arrogance and ignorance.

Then I learned that Proust didn’t refer only that one time to asparagus. Which brings us to a topic I have been exploring recently. Food and Art. Here is how Fran Lebowitz defined art a couple years ago, "If you can eat it, it's not art. If you can say 'I'll have that and a cup of coffee,' it's not art.” Brillat-Savarin, author of The Physiology of Taste (Physiologie du Goût), (published in1825 and translated into English by the food writer/memoirist MFK Fisher in 1949) would have disagreed. He wrote that “Poultry is for the cook what a canvas is for the painter.”

Proust made an entire writing career about food, so he certainly would have disagreed with Fran. Wandering through the literature on Proust and food (a passion second only to painting for me), I came upon James P. Gilroy who tells us this about Françoise, the cook who first worked for the narrator’s Aunt Leonie in Cambray and later for the narrator’s parents in Paris. One summer in Cambray, Françoise served asparagus nearly every day. Young Marcel appreciated all that asparagus. To him, “(t)heir stalks appear(ed) like celestial sylphs or disguised goddesses because of their brilliant colors…”

But there’s more here and it’s not pretty. Françoise served asparagus so often because she was hell bent on getting rid of the pregnant scullery maid. The one who had to pare the asparagus stalks. The one who was allergic to asparagus (morning sickness?). The one who Proust compared to Giotto’s figure of Caritas (Figure 11) in the Arena Chapel in Padua. Because she was so square, so matronly, so close to giving birth.

Figure 11. Caritas, Giotto, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1305

Oh well. Proust knew that Françoise could be crude and cruel but she certainly could cook. In fact, he thought they were kindred sprits. She used meat, bones and vegetables the way he used words. And they had a common goal, to create an organic and unified whole out of their respective raw ingredients.

Gilroy tells us this about Proust’s writings, “..the most profound revelations of essential truth can be inspired by activities associated with the consumption of food.” And this - “metaphor is the key to Proust’s conception of literature. To him, comparing two apparently different things, liberates the author and gives expression to the essence which is common to both. Food products, as well as their tastes and aromas, can bring to mind a person, a place, a work of art, a play, a flower.”

Here are a few of Proust’s metaphors. Françoise’s menus followed the rhythm of the seasons like the church’s liturgical calendar. Her kitchen was “a little temple of Venus,” to which farmers brought offerings of the first fruits of their fields.

To the narrator, Françoise’s preparation of a grand meal at his parent’s Paris apartment was comparable to Michelangelo’s preparation for his statue of Moses (the one with the horns) (Figure 12). As the sculptor traveled to Carrara to select the finest blocks of marble, so Françoise traveled to Les Halles to select the best ingredients.

Figure 12. Moses, Michelangelo, San Pietro in Vincole, Rome

Hannah Walhout has also written about Proust and food. Here is one of her favorite passages from Recherche. It is a late winter afternoon, Marcel is walking in Combray. The sun is setting with “a fiery glow which, accompanied often by a cold that burned and stung, would associate itself in my mind with the glow of the fire over which, at that very moment, was roasting the chicken that was to furnish me, in place of the poetic pleasure I had found in my walk, with the sensual pleasures of good feeding, warmth and rest.” As Proust walks, the sunset provokes images of the fireplace, the chicken roasting on it, the meal he will soon share with his family.

Here is Walhout on his madeleine, the tea and the memories provoked by dipping the one into the other as an adult. “Once that door opens, everything else comes rushing in: the village, the church steeple, the flowers and trees, the people of Combray, the people in the house, the people who made Marcel who he is.” As Walhout so aptly puts it, Proust “was a master of paying attention.”

Artistry replaced memory when an ordinary piece of stale toast was replaced by the evocative madeleine and its references to the scalloped shells worn by medieval pilgrims on their way to Saint Jacques de Compostelle. (Figures 13, 14).

Figure 13. Pilgrim Badge

Figure 14. Madeleines and madeleine tin

Áine Larkin tells us that for Proust, the scullery (back kitchen) was a liminal space, betwixt and between two fixed points. Between the raw (nature) and the cooked (culture). Betwixt a living chicken slaughtered and a roasted chicken served.

Larkin explains that Francoise’s “…culinary creativity shows the protagonist the fleeting nature of time, the specificity of place and the arduous requirements of creative endeavor – some of the most important themes of À la recherche du temps perdu.”

Here is Larkin’s own metaphor - through Francoise’s culinary example, Proust performed his own alchemy, he ‘transmuted’ his ‘sensory memories’ into ‘linguistic gold,’

It is profound, yet accessible. Paintings and patisseries were my way in, what’s yours?

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.