Ich bin immer noch ein Berliner! (I’m still a Berliner!)

Newsletter 06.16.2024

photo by @emilianovittoriosi @berlinphotostudio

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. One more look at the cultural richness that is Berlin (of which I have only scratched the surface) and then we’ll move on, or that is, back to Paris.

In the last week that Nicolas was here, in between frustrating and ultimately unsuccessful calls to Chase followed by endless conversations with my English speaking French banker, Nicolas and I walked and ate. Since he is interested in street art, not museum art, we mostly walked to lunch and then wandered home. We ate hamburgers at the Marché des Enfants Rouge and hotdogs at Clarks. He had choucroute de la mer at Bofinger and Périgord-style stuffed pork’s trotter at a new place for me but a Paris institution, Au Pied du Cochon. (Figs 1, 2) His Chinese girlfriend sometimes prepares pig’s feet and he wanted to compare French seasonings versus Chinese ones (Béarnaise vs soy sauce).

Figure 1. Nicolas eating one of our favorite dishes at Bofinger, choucroute de la mer

Figure 2. Périgord style staffe pork’s trotter, Au Pied du Cochon (a bit rich for both of us)

After our outings, he often went to the martial arts gym down the street from my apartment. And much later, after I was asleep, he was often out with a guy he met one night when they were both doing graffiti. His friend gets paid to paint the rolling panels that cover the doors of many closed stores in Paris. Between paid gigs, his friend hones his skills with graffiti. Here are a few examples of Nic at night. (Figs 3, 4)

Figure 3. Nic at night, (don’t know where this is) notice the ’shout-out’ to his MOM (top, center)

Figure 4. Nic at night (don’t know where) notice the BEV, bottom right

At the airport, our goodbye was bittersweet. He will be moving to China at the end of the year. I wonder if he’ll ever have a month to spend with me in Paris again. I just looked, there are flights on Air France from Paris to Beijing, so maybe…

Back to Berlin. (Fig 5) The mad dash that was the Discover Berlin Tour was a walking history course of well known sites, almost none of which can be associated with anything happy. We stood in a parking lot on top of Hitler’s Bunker and learned about the Fuhrer’s last days. We stood in front of the Gestapo Headquarters and heard about things I don’t want to think about. On the Bridge of Spies, it was Gary Powers and the Tom Hanks film. At CheckPoint Charlie, it was the restriction of movement between East and West Berlin that lasted for decades. And at a section of the Berlin Wall, we learned about the second, parallel fence that was erected on the East Berlin side in 1962. (Fig 6) That inner wall created a heavily guarded ‘no man’s land’ where people who dared flee to freedom were shot at by East Berlin guards. It reminded me of a book I read in French class, Un long Dimanche de fiançailles (the American film was called A very long engagement). It was about survivors of the cruel punishment the French military meted out to soldiers who self mutilated to avoid fighting during WWI. They were sent out into the ‘no-man’s land,’ bleak terrain between the French and German trenches. (Fig 7) Presumably to be shot at and killed by German soldiers.

Figure 5. Check-point Charlie, Berlin

Figure 6. Formerly the 'No man’s land’ between the walls, now a green belt with a past …

Figure 7. ‘No Man’s Land’ between the French - German trenches in World War I

Had I wanted to keep learning about Prussian and German history, I could easily and inexpensively have done so. Many of the city’s history museums are free.

Okay, here’s one good thing. When I was in Munich, no matter in what direction I turned, there was a sign for Dachau. In Berlin, the sign I recognized was for Spandau. That’s the name of the prison where Albert Spear, Hitler’s architect, spent 20 years of his life. I remember listening to him speak with David Frost after his release.

Both the Potsdam and Berlin guides spoke about a German-French rivalry. Which I never really thought about before. I mean, WWI & WWII eventually condemned Germany and rescued France. The guides often mentioned the Franco-Prussian War. France declared war on Prussia in July 1870. The Prussians invaded Paris and won the war 10 months later. I know about the conflict mostly because of what French Impressionist artists did during it. Some fled to England, others just got out of Paris and still others, like Frédéric Bazille, fought and died. When I think of France’s biggest rival, I don’t think of the Prussian Royal Family, the Hohenzollern, I think of the English Royal Family and the Seven Years War (1754 - 1763). Which started in America, where it was called the French and Indian War. I remember it because it kept the English artist William Hogarth from visiting France and learning about French rococo art first hand. I guess there are worse ways to see history than through the prism of art history.

The Discover Berlin tour ended at Checkpoint Charlie, only 1 km from the Jewish Museum (Figs 8, 9) which was designed by Daniel Libenskind, who also designed the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco (1984) and the original (2002 and since abandoned) masterplan for Ground Zero. And much more.

Figure 8. Jewish Museum, Berlin, designed by Daniel Libenskind

Figure 9. Jewish Museum, Berlin, designed by Daniel Libenskind, exterior detail

Since there was no temporary exhibition, I planned to focus on the architecture. But you can never escape history - not if you are in Berlin, not if it is Jewish. I learned that the first Jewish Museum on this site opened in 1933. Talk about bad timing! Six days later, the Nazis officially gained power. Five years later, on Kristallnacht, the Gestapo closed the museum and confiscated its collection. It wasn’t until the 1970s that a museum dedicated to the history of Jews in Berlin was considered. And another decade passed before a competition was held to select a designer for that museum. The Jewish Museum is two buildings. It wasn’t immediately obvious (well not to me) how to get into Libeskind’s building because the entrance is in the older building next door and the Libeskind building is only accessible from it via an underground passage.

Libeskind said he based his design on three concepts: “first, the impossibility of understanding the history of Berlin without understanding the enormous intellectual, economic and cultural contribution made by the Jewish citizens of Berlin, second, the necessity to integrate physically and spiritually the meaning of the Holocaust into the consciousness and memory of the city of Berlin, third, that only through the acknowledgement and incorporation of this erasure and void of Jewish life in Berlin, can the history of Berlin and Europe have a human future.” (Figs 10, 11)

Figure 10. Jewish Museum, Berlin, designed by Daniel Libenskind, interior

Figure 11. Jewish Museum, Berlin, designed by Daniel Libenskind, interior

I would say that ‘Void’ is a good word to describe Libeskind’s building. There are lots of empty spaces which represent "That which can never be exhibited when it comes to Jewish Berlin history: Humanity reduced to ashes.”

Another word is ‘Destabilization’ which I mostly experienced in the museum’s Garden of Exile. (Figs 12, 13) A sign says that you enter the garden at your own risk. The pathways slant, they are difficult and disturbing to walk along. The Berlin Holocaust Memorial is contemplative, this space was disconcerting. I didn’t stay.

Figure 12. Jewish Museum, Berlin, designed by Daniel Libenskind, Garden of Exile, enter at your own risk

Figure 13. Jewish Museum, Berlin, designed by Daniel Libenskind, Garden of Exile, enter at your own risk

As I was leaving the Jewish Museum, my telephone stopped working. I mean the GPS stopped working. I know you are supposed to turn it off and then turn it on again. And that’s what I tried to do but couldn’t. I was completely lost. The guard at the Jewish Museum suggested that I visit the Berlinische Galerie (Fig 14) which he assured me was just around the corner and down the block. So, that’s what I did. My philosophy is, when in doubt, go to a museum, preferably an art museum.

Figure 14. Berlinische Galerie, letters spell out all the names of artists whose work is displayed inside

When I got there, two young people were sitting on a bench in front. I sat down next to them and asked if either had an iPhone.They both did. I asked if they could show me how to turn mine off and back on again, hoping that whatever was bugging it would disappear. The young woman kindly did it and the GPS magically started working. As we talked, I learned that they were from Israel and then, that I was the only person they had felt at ease enough with since arriving, to tell. We agreed that it was a dangerous time to be from Israel but that ironically, they were probably safest in Germany. The young man had just completed his military service and was on his way to India, where, he told me, many Israelis go after their military service. I was happy to have met them, happy to wish them both well, happy that my GPS was working again!

The Berlinische Galerie was on the list of museums Noreene told me to check out. I’m glad I did. The permanent collection is an excellent introduction to German art from 1880-1980. The gallery’s website calls it a journey, “through time through Berlin: the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, the National Socialist dictatorship, the new beginning after 1945, the Cold War in the divided city and the alternative social and lifestyle concepts that developed in the shadow of the Wall in East and West.…” (Figs 15 - 18)

Figure 15. The Dancer Baladine Klossowska (Merline), Eugen Spiro1901

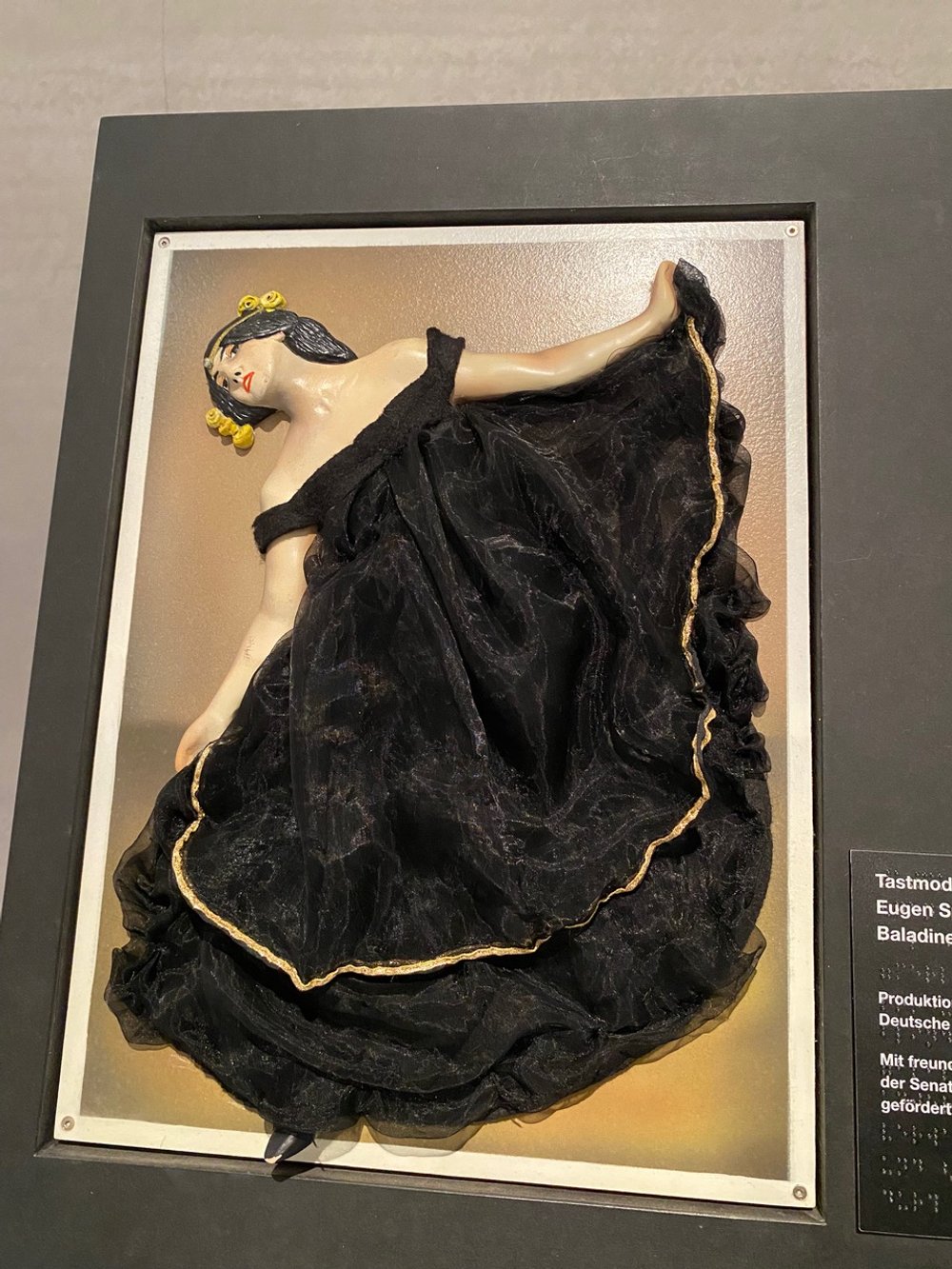

Figure 16. The Dancer Baladine Klossowska (Merline), 1901. This time in 3-D for blind and seeing impaired

Figure 17. Street Noise, Otto Moler, 1920

Figure 18. And here the above in 3-D

The temporary exhibitions were terrific. I concentrated on two. One was by the Franco-Algerian artist, Kader Attia who, according to the gallery’s website, “has been dealing with the principle of "repair" for many years, which he sees as a constant in nature and human history.” One of his exhibits, from 2016, is called, “J’Accuse.” A reference to Emile Zola’s condemnation of the French military’s handling of the false accusations against the Jewish army captain, Alfred Dreyfus. The exhibition includes 17 wooden busts and an 11-minute excerpt from an anti-war French film, also called ‘J’Accuse.’ The busts are a reference to the "gueules cassées,” (broken faces) (Figs 19 - 21) soldiers from WWI who suffered severe facial injuries. Some of these men’s faces were never repaired. I remember my French teacher, who was a little girl in Marseilles during WWII, telling us about an uncle of hers who had fought in WWI. Everybody thought he had been killed. Turns out, he and other soldiers with severe facial injuries lived in villages apart from society so that they would not cause their families pain.

Figure 19. Gueles Cassées, J’Accuse, Kader Attia, 2016

Figure 20. Gueles Cassées, J’Accuse, Kader Attia, 2016

Figure 21. Broken Faces, WWI

The second part of Attia’s exhibition is a 2020 video called "The Object's Interlacing.” In it, Attia discusses, with experts from various disciplines, the restitution of objects stolen during the colonial period from the cultures that had created them. “Restitution becomes a sort of repair…” (Figs 22, 23)

Figure 22. Looted Objects, Kadar Attia, 2020

Figure 23. Looted Objects, with film behind, “Object’s Interlacing,” Kadar Attia, 2020

Alongside his work, Attia included several collages by the German artist Hannah Höch, from her "From an Ethnographic Museum” (1924-30) series. Which she was inspired to create after a visit to an ethnographic museum. The series juxtaposes images of mostly white women from fashion magazines with reproductions of tribal art and masks. (Figs 24-26) Hoch’s collages are commentaries on the status of women in German society. Was the idea of the “New Woman” of the Weimar Republic - energetic, professional, androgynous, ready to take her place as man's equal, real? Or was the reality of how women were treated closer to how society treated ‘primitive people,’ like natives of Africa and Oceania, as infantile and inferior.

Figure 24. "From an Ethnographic Museum” (1924-30) series, Hannah Höch

Figure 24a (above without glare)

Figure 25. "From an Ethnographic Museum” (1924-30) series, Hannah Höch

Figure 26. "From an Ethnographic Museum” (1924-30) series, Hannah Höch

According to the museum, (i)t is Höch’s combination of magazine images of non-European works of art with images of the body and/or face of primarily white women from the 1920s, that creates an aesthetic of fragmentation and repair that inspired Kader Attia to integrate Höch’s works into his solo exhibition.”

The other temporary exhibition was called ‘Closer to Nature. Building with mushrooms, trees, clay.” (Figs 27-29) Here is the artist’s brief: “Architecture and nature are inevitably in competition. In view of finite resources and a constantly growing need for space, this fact becomes a dilemma. Added to this is the knowledge of the enormous amount of waste and emissions produced in the construction industry. All of this raises the question of a change of perspective in architecture today: Can we build with nature instead of against it?”

Figure 27. “Closer to Nature. Building with mushrooms, trees, clay”

Figure 28. “Closer to Nature. Building with mushrooms, trees, clay”

Figure 29. “Closer to Nature. Building with mushrooms, trees, clay”

The exhibition offered so many suggestions for better ways to live with nature and with each other. Somehow it seemed right, that here in Berlin, where so many awful things have happened, that suggestions for ways to live in harmony with each other and with nature should be in an art museum.

I promised you that this would be my last post about Berlin. But I have only managed to get through Day 3. I’ll save the museums I visited on Day 4 for another time - the Alte Nationalgalerie where I saw a temporary exhibition on the romantic artist David Caspar Frederick and the Neue Nationalgalerie, where there was a fabulous temporary exhibition on Gerhardt Richter. And the little Kathe Kollwitz museum, on the edge of the Schloss (Palace) Charlottenburg both of which I visited on my last day in Berlin, after a three hour tour of Cold War Berlin! But I won’t do it next week, I promise! Just a quick shout out to Berlin Photo Studio who recently moved into a storefront near the apartment we were staying. They invited us in and took our photograph. It’s a very special souvenir from Berlin. Thanks again for your Comments, they are much, much appreciated. Gros Bisous, Dr. B.

Copyright © 2024 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you!