I Shop Therefore I Am

Passage shopping

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. Today: a review of three exhibitions about advertising and merchandising.

First a thought about exhibitions. The people who develop them are just as interested in the exhibition catalogues as they are in the exhibitions themselves. It is through the essays and commentaries they write that their scholarship survives to be read and reviewed and referenced. All of which is to say that an exhibition isn’t over when it’s over, its second, more important life begins. Here.

The first exhibition I will tell you about was at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Caen, “The Spectacle of Merchandise, City, Art and Commerce, 1860 - 1914.” (Fig 1) The second exhibition, which you can see until 10/13, at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, is, ‘The Birth of the Department Stores. Fashion, Design, Toys, Advertising 1852-1925’. And the third exhibition, at the Bibliothèque Forney was in conjunction with Paris’ city-wide effort to bring Sports & Culture together for the Olympics. That exhibition, ‘Advertising in the City,’ focused on the Roaring Twenties.

Figure 1. Le Spectacle de la Marchandise. Art & commerce, 1860 - 1914

Why did the curators of the exhibition at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Caen ”choose the dates 1860 to 1914 for their exhibition? One source suggests that between 1860 and 1914, “cities (especially Paris) underwent unprecedented commercial development.” Let’s take a look at that. In 1860, Napoleon III was already ten years into his 19 year reign. Le Bon Marché, the first department store in Paris, had already been open for 8 years. And Baron Haussmann had already been at work for 7 years demolishing Paris’ medieval buildings and streets and creating wide boulevards that opened the city and connected the arrondissements to each other.

Perhaps 1860 is the date by which all those things began to kick in. Or maybe 1860 was chosen because of its importance to the art world. That’s the year Impressionism joined Realism in depicting subjects from Modern Life. (Figs 2, 3). The end date is more obvious, of course, the beginning of the Great War.

Figure 2. The Stonebreakers, Gustave Courbet, 1849 (painting now destroyed)

Figure 3. Raboteurs de parquet, Gustave Caillebotte, 1875 (Musée d’Orsay)

In mid-19th century Paris, buying and selling was everywhere. There were the stalls and shops and street vendors, of course. (Figs 4-7) And there was a new guy, a big guy, the department store, who began to muscle his way in. (Fig 8)

Figure 4. Flower Seller

Figure 5. Bonbon seller, P. Serusier

Figure 6. Bouquinistes, Eugène Atget, photo

Figure 7. Key maker, Eugène Atget, photo

Figure 8. Le Bon Marché, Felix Vallotton, Obsequious staff, imperious shoppers

One critic posited that the exhibition’s title, “The Merchandise Show,” can be understood in two ways. The conventional way, that visual artists began to ‘show’ department stores and shop windows. Which makes sense, that’s what artists began doing in France in the 19th century, painting the urban world around them.

The second way is creepier; that, commerce made of itself a “grand show,” to attract customers and entice them into buying their goods. The second idea connects with something another critic wrote, that Paris and other cities were open-air stores, designed for wandering and buying and now, more likely than not, eating, too.

The artists whose works are included in this exhibition, among them, Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Raoul Dufy and Félix Vallotton, became, as one critic noted,“privileged witnesses (to the) economic, visual and social transformations,” happening around them. Their images sometimes celebrate commercial exchanges and sometimes focus on their darker side. Scenes are depicted from various angles and numerous vantage points. Bird’s eye views from balconies and nearly worm’s eye view from a child’s perspective. Artists depicted the grands boulevards as well as the narrow streets that Baron Haussmann left unscathed. Even as they found subjects in department stores, they continued to be “(s)ensitive to the presence of street vendors, the gestures of milliners, the attitudes of waiters…” (Figs 9-13)

Figure 9. Boulevard de Clichy, Pierre Bonnard

Figure 10. Le Marché a Marseille, Raoul Dufy

Figure 11. La Rue Mouffetard, Maximilien Luce

Figure 12. Avenue de l’Opera, Camille Pissarro

Figure 13. Child Shopping, Edouard Vuillard

The exhibition included paintings and prints; photographs and films and also the ephemeral arts, advertisements in newspapers, sales catalogues and promotional items. Store owners thought about the layout of interior displays and exterior storefronts. Everything “that contributed to making the merchandise a spectacle.”

According to one scholar, merchandising was invented in the second half of the 19th century. It was Le Bon Marché, (a) “temple of luxury and abundance (that) elevate(d) the act of purchasing to the rank of a noble activity.” (Figs 14, 15)

Figure 14. Department Store, ’Temple of Luxury and Abundance’

Figure 15. Advertisement for Clothes for the Family

And shopping? That’s a 19th century term, too. It’s “the pleasure of comparing and evaluating goods. It constitutes a social, cultural and leisure activity.”

I took a graduate marketing course once, at the Wharton School. They had just started a Management and the Arts program and I was recruited to get an MBA. I didn’t but that’s not the point, well maybe it is but here’s one thing I did learn. The less stuff in a store window, the classier the store. H & M windows are stuffed with as much stuff as possible. Giorgio Armani, Christian Dior, those shop windows, nearly empty.

I have never been a fan of department stores. I don’t want to shop for everything at the same place. I don’t want more choices, I want a curated selection of choices. And the reason I like to shop during sales (not the first markdown, but the third) is less about saving money and more about having fewer choices. For me, the one way a salesperson can make sure that I won’t be buying something is to say that ‘everybody is buying’ it. I don’t want the approbation of the masses!

So maybe I’m not the best person to be writing this review and yet I can’t help but find it fascinating that what we consider normal, being inundated with advertisements for everything from cameras to candidates, started somewhere and that somewhere was here, in Paris, 172 years ago, 1852 to be precise.

The exhibition at MAD takes as its subject the birth and development of department stores during a 75 year period, from the Second Empire (1852-70), to the Belle Epoque (1871-1914), through the Great War (1914-1918) and to Les Années Folle (1920s). Starting with the creation of the first department store (Le Bon Marché in 1852) and culminating with their consecration at the 1925 Paris International Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts.

You’ll recognize many of these department stores, they’re still around, Le Bon Marché, Le Printemps, La Samaritaine and Les Galeries Lafayette. (Figs 16-18). How many employees did it take to keep a department store running? More than you might think. A short film at the exhibition in Caen took as its subject the large number of cooks and servers required to feed the staff. And those were people who weren’t even directly involved with the customers!

Figure 16. Paris Department Stores locations

Figure 17. Le Bon Marché

Figure 18. The department store employees

The exhibition is huge, overwhelming really. More than 700 pieces, many from the museum’s own collection, to tell the story of the department store. And like a department store itself, everything is here, including the kitchen sink. There are advertising posters and toys targeting the most innocent of eyes; clothes and accessories for everyone; furniture and decorative arts for everywhere. (Figs 19-21)

Figure 19. Advertisement for Le Printemps

Figure 20. Boy Games & Toys & Clothes

Figure 21. Girls Dolls

We are introduced to the men and women who created the Parisian department stores, beginning with the couple who founded Le Bon Marché, Aristide and Marguerite Boucicaut,(Fig 22) Emile Zola’s inspiration for Le Bonheur des Dames. The Boucicauts were model entrepreneurs. They laid the foundation of modern commerce. They piqued their customers’ interest with changing seasonal displays; they had sales to keep merchandise moving in preparation for the next season’s arrivals. And they targeted children through advertisements and child’s eye level displays.

Figure 22. Aristide & Marguerite Boucicaut, creators of Le Bon Marché

Le Bon Marché and other department stores had one audience in mind, the newly emerging bourgeoisie. Specifically the wives of the businessmen who earned more money than the landowning aristocrats and nobles had inherited. These newly wealthy people had newly found leisure time. “Going shopping” became an activity as acceptable as going to the theatre or a concert. (Figs 23, 24)

Figure 23. Women Shopping

Figure 24. Women Window Shopping

Ironically, (or not), department stores arrived at around the same time as the “flaneur,” (Fig 25) defined as the man who could casually saunter along the newly created boulevards of Paris, observing everything around him, looking without being noticed.

Figure 25. Edouard Manet as Flaneur, Henri Fantin-Latour

There was no such thing as a “flaneuse,” at the time, that is, a woman who could freely walk the streets of Paris, observing without being harassed. Women were the subject of the Male Gaze. So if a respectable woman wanted to be out and about on her own, one of her few options was the department store. They were designed as places where women could safely relax and socialize away from their husbands. Where they were welcomed as guests as well as customers. That must have been a radical concept at the time.completely antithetical to the small shop experience. Where, if you weren’t there to buy something, there really wasn’t enough space to browse, to linger.

In department stores, a woman wandering was a very good thing for the store owner. Because as women wandered, they happened upon items they didn’t know they wanted, didn’t know they needed, might not even have known existed.

Department store owners did all they could to entice their captive audiences, products were beautifully displayed, juxtaposed with other items, set up in front of lavish backdrops. Starting as a passion, it became, to many, an addiction. (Fig 26)

Figure 26. Women’s undergarments for sale

A section in the exhibition is about ready-to-wear apparel, made possible by the mechanization of the textile industry. Outfits with matching accessories were produced in bulk and sold as ensembles. (Fig 27) The economic model was one with which we are all familiar, a reduction of quality and salaries and margins. The beginning of fast fashion. The consumer gets a bargain, but at what cost, to society, to the environment?

Figure 27. Advertisement for Mens and Boys clothes

The monthly calendar of shopping, which we all still follow today, started in the mid 19th century, too. In January, it was the White Sales; (Fig 28) in August, it was the Rentrée, (Back to School). December was about children, especially toys. Toys quickly became, like children’s clothing did, a new, year-round commercial target.

Figure 28. Le Bon Marché advertisement for Annual January White Sales

When they first appeared, department stores were heralded as the new best thing These days, they no longer have the same caché. Macy’s Union Square is closing in San Francisco; in Paris, except for the tourists, La Samaritaine is mostly empty. Now we shop online, scouting out bargains, free shipping and easy returns.

The 19th century department stores foresaw shopping from home, too. They had mail-order catalogues with lots of illustrations, of everything from umbrellas and canes to tennis rackets and bicycles, etc. etc. etc.

As the reviewer from the Guardian so chillingly writes, “The gaudy medley of merchandise and materialism makes for an entertaining … show, but the overall effect might make you feel a bit nauseous. This is where the epoch of unbridled consumerism began, where marketing methods were refined, sales techniques honed, and the global addiction to acquiring more stuff originated.” Yes, that sums it up.

The exhibition at the Bibliotheque Forney, “Advertising and Paris in the early 1920s,” (Fig 29) takes as its focus, the tail end of the enormous exhibition at MAD, the Années Folles,’ the Roaring Twenties. When “advertising became more professional, reached new media and explored new avenues.…” By examining the mountains of advertising that was produced, the exhibition contends that it is “possible to understand the city of 1924, its current events, its appearance, its atmosphere... (and) the place of sport (in) society of the time.” The exhibition had five themes: ‘Political Propaganda,’ which had been intense during the Great War, and which continued to be utilized in the years that followed. There was a section about the growing professionalism of Selling and Advertising, with the United States, not surprisingly, taking the lead in improving selling techniques. Another section, ‘Parisian Businesses Advertising Their Wares,’ showed how big businesses used current events, like the Olympics, to sell stuff. The fourth and fifth sections, ‘Artists at the Service of Advertising,’ and ‘An Invitation to the Show,’ take as their subject the moment when real artists started creating posters and posters became works of art.

Figure 29. Paris 1924. La Publicité dans la Ville, exhibition Bibliothèque Forney, Paris

It was a fabulous decade, too good to be true. It ended with a crash, a great one, the Crash of 1929. (Figs 30 - 36). These three exhibitions help explain how we got to where we are today with advertising and marketing impacting so many aspects of our daily lives in profound and important ways. Gros bisous, Dr. ‘B.’

Figure 30. Posters encouraging women to vote

Figure 31, L’Emprunt de la Paix.(Peace Loans) With the end of the war, life should get back to normal - women at home with their children, men working to reconstruct the country

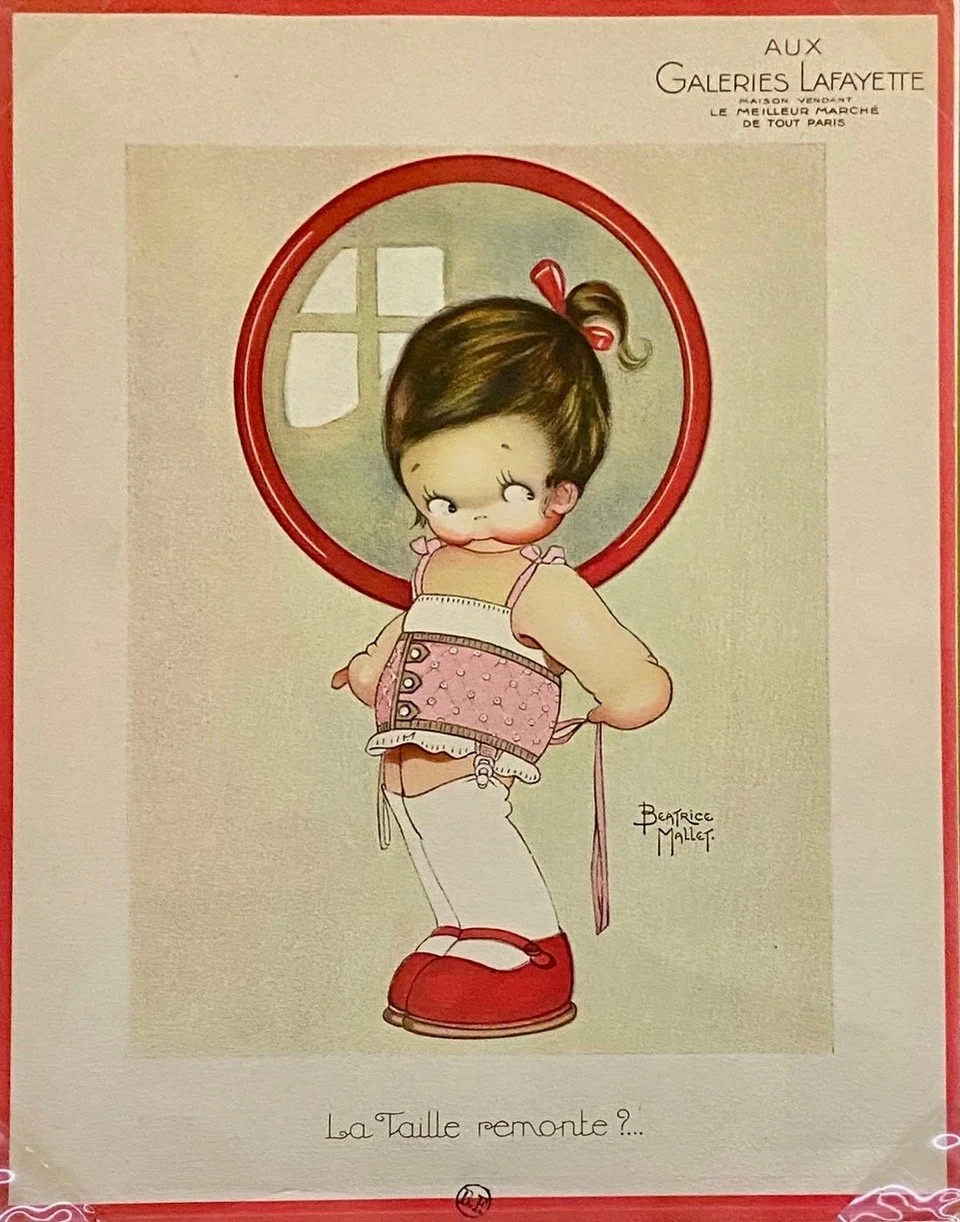

Figure 32. Advertisement for Galeries Lafayette

Figure 33. Poster advocating for an 8 hour work week

Figure 34. Olympic Cyclists with Wolber Tires

Figure 35. Jeux Olympiques, Paris 1924

Comment are always gratefully received. Merci!

New comment on One stitch at a time:

What an astonishing exhibition on round the corner from you. I'm so glad you got the chance to see that one as well as the amazing architecture at L19M and the Maison Lesage. Rich pickings this week! Katherine, Oxford, England