The Iconography of an Icon

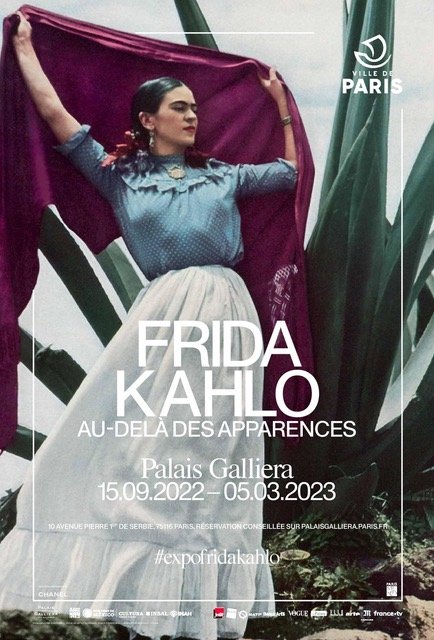

Frida Kahlo at the Palais Galliera

If somebody had asked me to say something about Frida Kahlo before I saw the exhibition now on at the Palais Galliera, ‘Friday Kahlo au-delà des apparences (beyond appearances)’ I would have started with the obvious, the cliches - unibrow, mustache. And I would have repeated something I remember reading that Frida Kahlo had said about herself and her husband, the muralist, Diego Rivera. She said that she had more facial hair but that his breasts were bigger. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Photograph of Frida Kahlo and husband Diego Rivera, 1931

I would also have said that when I read Ann Patchett’s biography of her friend, the poet Lucy Grealy, (Truth and Beauty) I thought of Frida Kahlo. Grealy was disfigured by jaw cancer when she was 9. Frida’s spine was broken in a traffic accident when she was 18. Both underwent numerous surgeries. Which were followed by long periods of convalescence. Then more surgeries and more convalescences. Both women, or so it seemed, let disfigurement and pain define them and their art. Since I don’t know anything more about Lucy than what I read in her memoir (Autobiography of a Face) and Ann Patchett’s book, my thoughts about her have stalled.

But this exhibition offers a nuanced examination of Frida Kahlo’s life and art, which permits a more nuanced appreciation of both.

What’s here that has not unavailable before? Simply put, more than 200 objects that have not previously been seen or even known about, from Casa Azul, (Figure 2) the house where Frida was born, where she lived with her sisters and parents, where she shared a life with her husband, and where she died in 1954, at age 46.

Figure 2. Museo Frida Kahlo, Casa Azul, Mexico

These object include the traditional Mexican clothes that Frida famously wore. On some of which are paint flecks because she wore them while she worked. All show signs of wear, because they were her everyday clothes, not costumes for when she was photographed or when she painted her self portraits. (Figure 3) There are some of the pre-Columbian necklaces that Frida collected and wore. And there are lots of letters, from her many lovers, men and women, Mexican, French, English and at least one (famous) Russian. There are medicines and cosmetic bottles, (Figure 4) some empty, some half used, some sealed, still in their original packaging. And (for me) the most revealing items, plaster corsets and leather ones that Frida wore under her clothes. (Figures 5, 6)

Figure 3. Sampling of Dresses and Skirts & Tops owned & worn by Frida Kahlo, exhibition, Palais Galliera

Figure 4. Cosmetics, from Casa Azul, exhibition Palais Galliera

Figure 5. Plaster corset decorated with unborn fetus and sickle and hammer, exhibition. Frida Kahlo

Figure 6. Leather Corset, Frida Kahlo exhibition Palais Galliera

As I say, all this stuff was at the Casa Azul. But Frida died in 1954. What’s going on? Here’s the story I have been able to piece together. When Frida Kahlo died, Diego Rivera transformed the Casa Azul into a museum, putting the items that are on display here as well as many, many others, into a bathroom and dressing room which he locked. Three years later, as he was dying of cancer, he gave the keys to his dear friend and patron, Dolores Olmedo (Figure 7). He asked her not to open the bathrooms until 15 years after Frida’s death. He was worried that “his wife's legacy would become politicized during another volatile period of upheaval in the country's history…” .

Figure 7. Diego Rivera painting a portrait of his patron Dolores Olmedo dressed in Mexican traditional costume

Okay, fair enough, but if Friday Kahlo died in 1954, why weren’t the rooms opened in 1969, as per Diego’s wish. Two words, Dolores Olmedo. Who, when Diego died in 1957, became the director of the Casa Azul. And just coincidentally also opened her own, rival museum, filled with mostly Diego’s art.

Dolores was in charge of what happened at the Casa Azul for a very long time. Because even though she was only one year younger than Frida, she was 94 when she died in 2002. So, as it turns out, there’s no great mystery about why those rooms remained locked for so long, it’s just garden variety vindictiveness and jealousy.

In an interview with a reporter for the LA Times in 2004, Olmedo’s son, who became the director of both museums when his mother died, said, “Diego asked my mother not to open them (the rooms) for 15 years. And my mother decided not to open them at all!” He continued, “I know my mother didn’t like Frida.…” His own memories of Frida? “I just remember a lady that was disagreeable, dirty, smelled bad and was in bad humor.….”

Phillips insisted that his mother and Diego were never lovers. But (that) their friendship (drove) a wedge between her and Kahlo and a rift between Diego and Phillips’ father. Phillips suggested that their rivalry might have been a result of their similarities. Both were bohemians, both dressed like Indian peasants and both modeled nude for Diego. I’m not buying it, Diego had lots of affairs, with lots of different women. Maybe this one didn’t end well, or maybe didn’t end at all….

According to the current director of the Frida Kahlo Museum, Hilda Trujillo Soto, because of Dolores’ decision, “…time stopped at the Casa Azul for almost 50 years… Dolores Olmedo did not speak about these spaces,” even though some Kahlo scholars knew about the rooms and asked her to open them. She refused. She had the keys.

According to Soto, Dolores just “respected Diego’s will for longer than he requested” because she “did not have a close relationship with Frida.” That’s very diplomatic, maybe Dolores’s son was listening when she said it.

Two years after Dolores died, in 2004, the rooms were finally opened. It took historians four more years to catalogue the 6,000 photographs, 12,000 documents and 300 items in those rooms. The exhibition at the Palais Galliera and the one that preceded it at the V & A in London offer us a taste of what was in them.

The focus of the exhibition at Palais Galliera is how Frida used fashion to celebrate her many identities - as a woman, as a Mexican, as a handicapped person, as a Communist, as a bi-sexual person.

The exhibition moves chronologically and thematically from Frida’s birth in 1907, one of four sisters born to a German father and Mexican/Spanish mother. When Frida was six, she contracted polio. Her right leg atrophied and her foot stopped growing. But she was bright and she planned to go to medical school. That dream ended when she was 18, when she injured in a horrific bus accident. She was impaled by a metal rod and suffered multiple fractures of her spine, collarbone and ribs. Her pelvis was shattered, her foot was broken and her shoulder was dislocated. She was operated on. She was put in a body cast. She spent months in bed recuperating. Polio had made her a handicapped person at age six. Twelve years later, everything got much much worse.

There was a single sliver of a silver lining. She had always been interested in art and those first months of enforced immobility sealed the deal. Her mother bought her a frame and set up a mirror that allowed Frida to paint lying in bed. (Figures 8, 9) She said, “I am not sick. I am broken. But I feel happy to continue living, as long as it is possible for me to paint.” For her, painting was a reason to live.

Figure 8. Photograph of Frida Kahlo painting in bed

Figure 9. Photograph of Frida Kahlo painting in bed

Over the next 28 years, as she pursued her career, as she traveled the world, as she developed friendships and enjoyed multiple love affairs, she underwent 30 more medical procedures. Each followed by time in bed recuperating. But she never got better. Her last operation, in August 1953, was the amputation of her gangrenous leg.

Of her 150 paintings, one third are self-portraits. They were her way of taking control of what was happening to her, of understanding what was happening to her. For example, the self portrait called Henry Ford Hospital was painted in 1932. (Figure 10) Frida lies in a hospital bed, in a pool of her own blood, attached by umbilical cords to various objects, among them a fetus and a pelvis. Frida had become pregnant but her body was not strong enough to support the pregnancy. She miscarried while in Detroit, an emergency operation followed.

Figure 10. Self portrait, Henry Ford Hospital, Frida Kahlo, 1932

In another painting, The Broken Column (Figure 11), Frida depicts herself with a bare torso, split down the middle, her spine a broken Ionic column. Nails prick her skin, spots of blood surface. We can’t help but think of Christ’s Passion (Figure 12) Her body is supported by the surgical brace.

Figure 11. Self Portrait, Broken Column, Frida Kahlo, 1944

Figure 12. The Dead Christ, Jacopo Palma the younger, 1548

Those surgical braces are on display here, (above Figure 6) as is the prosthetic leg with a red leather boot. (Figure 13) Also here are the plaster corsets she initially wore to support a spine that wasn’t strong enough to support itself. (Figure 14) She didn’t permit them to be loathsome symbols of her handicap. Usually hidden under her clothes, they touched her body. She painted them and made them beautiful for herself.

Figure 13. Leg and Foot prothesis, Frida Kahlo

Figure 14. Frida Kahlo wearing plaster corset

Circe Henestrosa, the curator of the exhibition at the V & A calls them a testament to how Frida ‘fashioned’ her disability. “Kahlo never let her disabilities …define her, she defined who she was in her own terms.”

In another self portrait, this one from 1948, Frida’s face is surrounded by a halo of lace. (Figure 15) The women of Tehuantepec, in SW Mexico traditionally wore these headdresses, called resplandors, (Figure 16) during Mass, weddings and processions. They are modeled after the crowns worn by statues of the Virgin Mary. During Mass, the headdress resembles a cape. For other ceremonies, the wide frill is flipped to frame the face. Exactly as Frida wears it here. A documentary film in the exhibition shows young girls turning their headdresses from cape to face frill.

Figure 15. Self Portrait in Tehuantepec Lace headdress - unibrow & mustache, too!

Figure 16. Mannequin dressed in Resplandor

Frida’s clothing has multiple meanings. Her wardrobe of traditional Mexican dresses and skirts and tops is, of course, a celebration of her Mexican roots. Those dresses, skirts and tops were also roomy enough to hide her plaster corsets. Also, it seems to me, for such a tiny person, those clothes helped her navigate her place in Mexico’s macho culture. Her clothes gave her volume. The flowers in her hair gave her height. (Figure 20) She used them to create a more formidable presence for herself.

As the director of the Frida Kahlo Museum writes, Frida’s locked rooms have changed our perception of Frida from a “sufferer” to a “strong woman.”

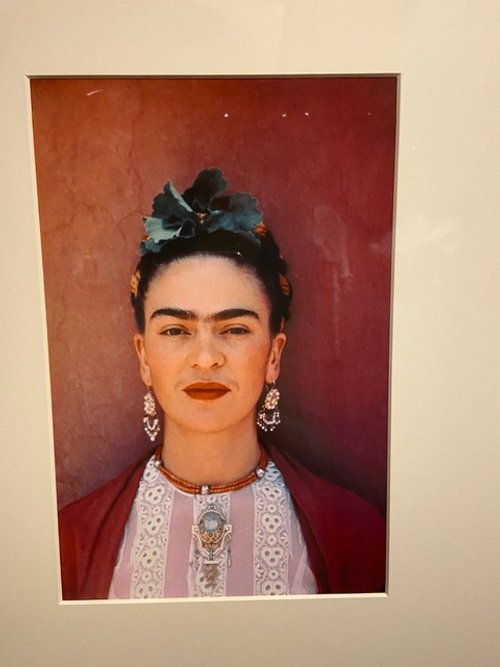

But wait, what about her unibrow and facial hair. (Figure 17) Both of which might seem frivolous but neither of which, the current thinking is, were. She could have plucked the hair between her eyebrows like everyone else, but she chose to accentuated it instead with an eyebrow pencil like the one in the exhibition. It was a way of showing that she was not going to conform to imposed standards of beauty.

Figure 17. Photograph of Frida Kahlo with unibrow and mustache prominent

She also challenged gender stereotypes, beginning when she was quite young. In a family portrait, Frida wears one of her father’s suits. (Figure 18). She continued to play with gendered identity throughout her life.

Figure 18. Frida and family portrait, Frida is in center dressed in her father’s suit

And then there were her politics. Frida was a Communist. When she told people that she was born in 1910 rather than her actual year of birth, 1907, it wasn’t because she wanted people to think she was younger, it was because she wanted her date of birth to coincide with the Mexican Revolution.

Among her many lovers was Leon Trotsky. When he was granted asylum in Mexico, Diego invited him to stay at Casa Azul. Frida welcomed him by taking him as a lover. She painted a self portrait and dedicated it to him. ((Figure 19) When Trotsky and his wife left Mexico, they left the portrait behind, at Trotsky’s wife’s request.

Figure 19. Self Portrait by Frida Kahlo dedicated to Leon Trotsky, 1937

You’d think that with as much physical pain as she endured, Frida would have sought as calm a personal life as possible. But that wasn’t what happened. She said once, “I have had two serious accidents in my life. One was when a tram ran over me. The other is Diego,” (Figure 20)

Figure 20. Photograph of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

Frida’s marriage to Diego was always tumultuous and often traumatic. Frida had affairs with both men and women. Diego had plenty of affairs, too.

But when Diego and Frida’s sisters became lovers, Frida divorced him. That was in 1939. Right after the divorce, Frida painted Self Portrait with Cropped hair. (Figure 21) Seated in a man’s suit, with scissors in her hand. She has cut her hair off, it lies around her on the floor. The lyrics of a song are painted across the top, ”See, if I loved you, it was for your hair, now you're bald, I don't love you any more.” Frida and Diego remarried a year later. (FYI - I wrote about Kiki Smith at the Musée de la Monnaie a few years ago. She used Frida’s self-portrait as the starting point for her sculpture of the Annunciation, a version of which is at the Fondation Louis Vuitton (Figure 22)

Figure 21. Self Portrait with Cropped Hair, Frida Kahlo, 1939

Figure 22. The artist Kiki Smith referenced Frida Kahlo’s self portrait in this sculpture of the Annunciation

Frida and Diego traveled to San Francisco, Detroit and New York. Frida went to Paris alone. While there, Elsa Schiaparelli was so impressed with her style, that she designed the Madame Rivera dress. Marcel Duchamp and his wife organized a solo show of her work in Paris when André Breton didn’t follow through on his offer to do so. But whether they were together or alone, in Mexico or abroad, Frida was Diego’s wife. Now Frida is better known than Diego.

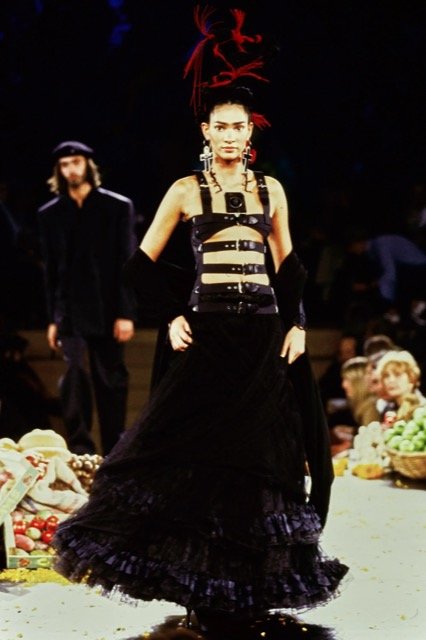

Since this is a fashion museum, there is a second exhibition here. It is a mostly joyful, although sometimes macabre, celebration of Frida’s influence on contemporary designers. Both her reality and her image inspired designers from Jean Paul Gaultier and Karl Lagerfeld to Riccardo Tisci for Givenchy, Maria Grazia Chiuri for Dior and Rea Kawakumbo for Comme des Garçons.(Figures 23 - 30) It’s a fun and inspiring way to conclude a sometimes sombre, sometimes joyful but always respectful exhibition on the life and art of Frida Kahlo.

Figure 23. Alexander McQueen for Givenchy riffs on Frida’s plaster and leather casts

Figure 24. Maria Grazia Chiuri for Christian Dior riffs on both plaster & leather casts and male dressing

Figure 25. Jean Paul Gautier’s riff on leather corset and high headdresses

Figure 26. Karl Lagerfeld’s riff with Claudia Schiffer in headdress with unibrow

Figure 27. Another Jean-Paul Gaultier homage - everyone loves leather

Figure 28. Riccardo Tisci for Givenchy

Figure 29. Franc Sorbier for Valentino

Figure 30. Rea Kawakumbo for Comme des Garçons