Brancusi is Breathtaking at the Centre Pompidou

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and Art. This week: an exhibition I saw and then saw again at the Centre Pompidou. A retrospective on the work of Constantin Brancusi. It is so moving, it is so rich, that if you are here or are going to be here before it closes on 1st July, I urge you to see it. My review follows the exhibition’s themes, with lots of photos. (Fig 1)

Figure 1. Brancusi, Centre Pompidou Exhibition, (my poster)

A few years ago, when we were in the throes of the pandemic, when everything was closed, by which I mean museums and then even galleries, when writing about temporary museum exhibitions was not a possibility because there were none, I shifted focus and wrote a series of posts about museums dedicated to individual artists - Zadkine, Bourdelle, Maillol, Giacometti, Rodin and Brancusi. The first five all have their own museums, Brancusi’s real estate may be the smallest but it is probably the best, or at least the most visible. A recreation of his studio sits in front of the Centre Pompidou, designed by the architect who designed that museum, Renzo Piano. (Figs 2, 3)

Figure 2. Exterior Brancusi Studio, piazza in front of Centre Pompidou, temporarily closed 2024

Figure 3. Interior Brancusi Studio, Centre Pompidou, temporarily closed 2024

Figure 3a. Brancusi studio partially reconstructed for this exhibition

When I was doing research on Richard Serra a few weeks ago, I learned that he began to take sculpture seriously when he visited, and then re-visited and then visited again the recreation of Brancusi’s studio, then at the Musée de l’Art Moderne. (Fig 4)

Figure 4. Brancusi-Serra Exhibition at Beyeler Foundation, Switzerland & Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, 2011-2012

For the exhibition I am going to tell you about now, Brancusi has moved out of his studio on the piazza and into the museum itself. Onto the sixth floor of the Centre Pompidou where some of his works have been perfectly sighted to celebrate the breathtaking views of the city of Paris which on a clear day you can see from there.

Here is the first review I wrote about Brancusi. Brancussi: the Sculptor of the Essence. This review is different, except the set-up.

In 1876, Constantin Brancusi was born in Romania to peasants whose back breaking work was all their son knew. At 7, Constatin was herding the family’s flock of sheep. At 9, traumatized by the brutality of his father and older brothers, he escaped his family and his village by walking to the nearest town and finding work, first at a grocery store and then at a bar. Just before he turned 18, a wealthy industrialist noticed his talent for carving. And in a single stroke, to be seen by the right person at the right time, the trajectory of his life changed. The industrialist paid for him to attend an arts and crafts school in Bucharest from which he graduated four years later.

At 9, he had walked away from his family and village. At 27, he walked toward his future, to Paris. He arrived on July 14, 1904 having turned 28 on the road. (Figs 5, 6)

Figure 5. Brancusi with backpack on way to Paris 1903-04

Figure 6. The photo above reminds me of: Bonjour Monsieur Courbet, Courbet, 1854

He came to Paris with a scholarship to study art. But he needed money for food and lodging. He worked as a sacristan at the Romanian Orthodox church and he washed dishes at the Bouillon Chartier. Brarncusi probably appreciated both the food and the patrons. Bouillons were the brainchild of a Paris butcher who saw a need and figured out how to make money filling it. He sold hungry working men hot meals at low prices. The Chartier brothers opened their bouillon in 1896. It is still going strong. (Fig7)

Figure 7. Chartier Bouillon, which I walked by a few days ago

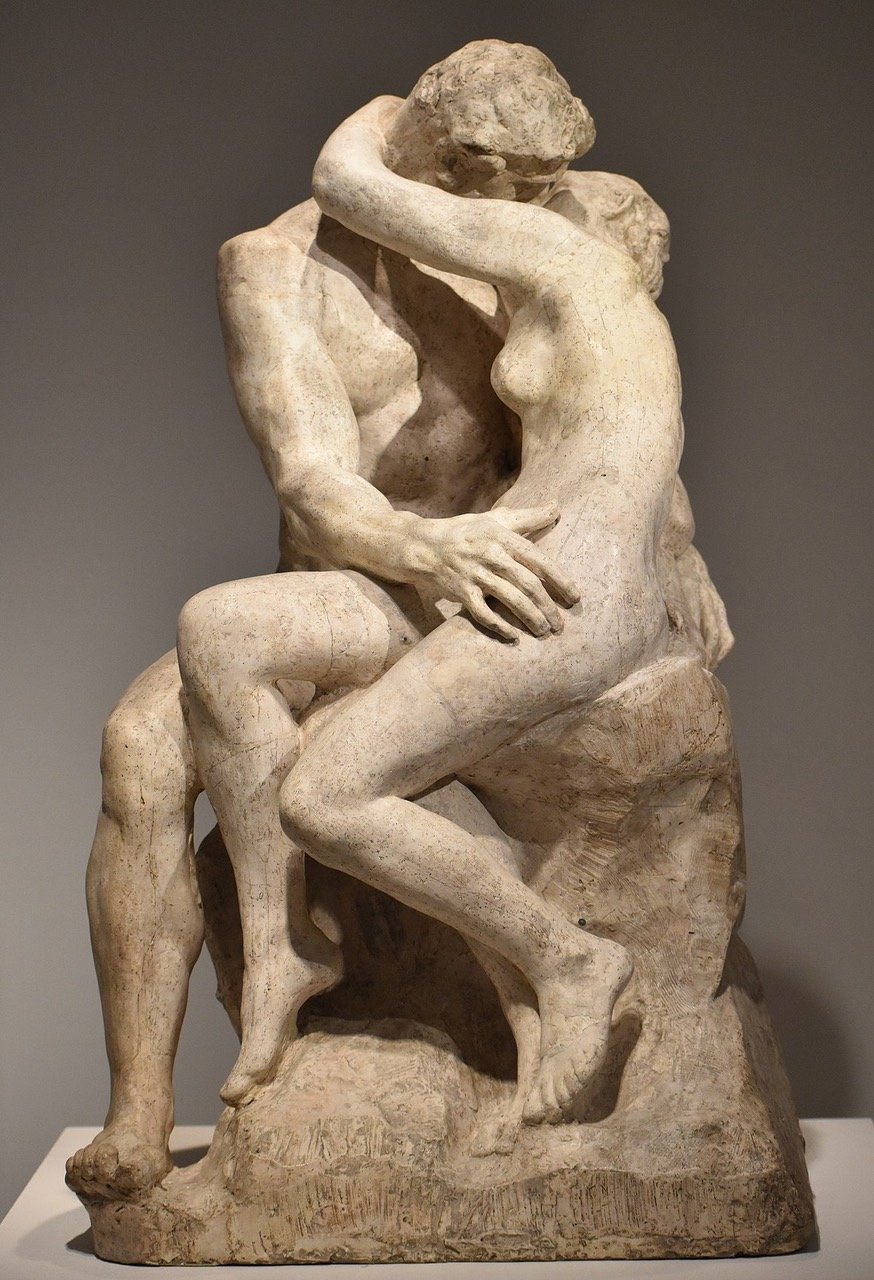

This exhibition is divided into 9 sections. The first is entitled, “Origins of a New Language.” In 1907, Brancusi was invited to join Auguste Rodin’s studio. After a month or two, reports vary, Brancusi left, explaining years later that “Nothing can grow under big trees.” Better, Brancusi thought, to struggle on his own than be eclipsed by Rodin’s shadow. Working with Rodin helped Brancusi understand himself. Rodin was Brancusi’s foil. Unlike Rodin, Brancusi didn’t model, he carved directly into his material. Unlike Rodin, Brancusi didn’t use models, he based his forms upon memory, upon imagination. His process was fragmentation and simplification. His goal was to find “the very essence of things.” This simplification and search for the essence transformed Sleep into The Sleeping Muse. (Figs 8, 9) Head of a child into Newborn. (Figs 10, 11) In 1907-08, Brancusi produced his signature work, The Kiss (Figs 12, 13) - which compared to Rodin’s Kiss, is the definition of essence, simplification.

Figure 8. Sleep, 1908

Figure 9. Sleeping Muse, 1910

Figure 10. Head of a child (George) 1911

Figure 11. Head of a newborn, 1923

Figure 12. The Kiss, Brancusi, 1907, THE ESSENCE

Figure 13. The Kiss, Rodin, 1882. THE OVERSTATEMENT

Brancusi may have forged his own path but he was well aware of art from other periods and places as well as his own. Scattered throughout the exhibition are references to classical art, (his training in Bucharest included drawing from casts of Greek and Roman statues) the arts of Africa and works by his contemporaries like Paul Gauguin. Here, too are examples of wooden arches and doorways, the visual world that surrounded Brancusi before he walked to Paris. (Figs 14, 15, 16)

Figure 14. Male statue, Mali

Figure 15. Oviri, Paul Gauguin, 1894

Figure 16. Traditional Romanian arched doorway

The second section is entitled, “The Studio.” Brancusi's studio, located at 8 impasse Ronsin, was one of many in that impasse. (Fig 17) When he bequeathed his studio to the French state, he stipulated that his studio had to be preserved exactly as he left it. He assumed the state would leave it where it was. He happily told his fellow artists that his deal would protect their studios. Alas, that’s not what happened. The contents of Brancusi’s studio were removed and the studio was recreated. All the studios were destroyed for an expansion of Hospital Necker.

Figure 17. Brancusi’s studio, Impasse Ronsin, one of many here off rue Vaugirard, 15th arrondissement

Brancusi occupied his studio for 41 years, from 1916 until his death in 1957. He created everything, the huge limestone fireplace and the wooden stools and plaster tables which were both furniture and pedestals. In photographs and films, we see him carving, sawing, modeling. (Figs 18, 19) After World War II, Brancusi stopped creating. He wanted his studio to stay as it was. Whenever he sold a work, he replaced it with its plaster or bronze mold. The studio became a work of art. Brâncuși didn’t give interviews and didn’t work with any agents. If someone wanted to buy something Brancusi made, they would have to visit the artist in his studio to do so.

Figure 18. Brancusi working in his studio

Figure 19. Brancusi sawing in front of his studio (left), Brancusi sitting in his studio (right)

Margaret Anderson (founder/editor of Little Review) visited Brancusi in 1921. She wrote this: “Constantin Brancusi lives in a stone studio … His hair and beard are white, his long working-man's blouse is white, his stone benches and large round table are white, the sculptor's dust that covers everything is white, his Bird in white marble stands on a high pedestal against the windows, a large white magnolia can always be seen on the white table. At one time he had a white dog and a white rooster.”

This is what May Ray said about Brancusi’s studio: “The first time I went to see the sculptor Brancusi in his studio, I was more impressed than in any cathedral. I was overwhelmed with its whiteness and lightness. ….] Coming into Brancusi's studio was like entering another world.” (1963)

Masculine & Feminine. With Brancusi, masculine and feminine merge. When shapes are simplified and details are suppressed, ambiguity results. His 1909 Woman Looking at Herself in a Mirror, for example, is a more or less a classic nude, which ten years later, became Princess X. (Figs 20 - 22) Is it a female or a phallus? Is it an idealized woman or an erection? Is it a woman with a long neck (“the very essence of Woman Eternal”) that just happened to look like an erect penis and testicles. The sculpture caused a scandal and was banned from the 1920 Salon des Indépendants.

Figure 20. Woman Looking at Herself in a Mirror, 1909

Figure 21. Photo of Princess X

Figure 22. Princess X

Despite the title, Torso of a Young Man (Figs 23, 24) seems more feminine than masculine. There is no indication of gender where the torso meets the thighs. Does The Kiss represent a man and a woman? Does it matter? One commentator notes that by “disrupting the symbolic order of the division of the sexes, (Brancusi’s) works echo the Dada spirit of protest, advocated by his friends Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and Tristan Tzara.” And these sculptures are also very ‘woke.’

Figure 23. Torso of a Young Man

Figure 24. Torso of a Young Man (a little less shiny!)

Portraits. Brancusi sculpted portraits of his mostly female friends. Since he was not interested in outer appearance but in the essence of the person, he worked from his memory rather than a model. Not surprisingly, although the portraits have names, like the English writer/heiress Nancy Cunard or the Hungarian painter Margit Pogany, their features are more or less interchangeable. One sculpture might have almond eyes, another smooth hair, another curly hair, (Figs 25-27) but as the wall text notes, “Brancusi's portraits raise the question of resemblance and representation.”

Figure 25. Portraits on plinths

Figure 26. Portrait with Almond Eyes

Figure 27. Portrait with Smooth Hair

Flight. For more than thirty years, Brancusi worked on his sculpture Bird in Space, 10 of the 27 variants in plaster, marble and bronze are in the exhibition, ready to fly off from one of the best perches in town. (Figs 28, 29) Bird in Flight didn’t just happen, of course, it began in 1910, with the Maïastras, (Fig 30) Brancusi’s rendition of birds from popular Romanian fairy tales, with their rounded bodies, long necks and wide-open beaks. In the 1920s, the sculptor began simplifying the shape, thinning it down, stretching it out. According to the curators, the Bird in Flight “represents both man's dream of flying and humankind's dream of escaping its earthly existence, its ascension towards spirituality.” When I saw all these Bird in Flight sculptures, I felt exactly what Marcel Duchamp described, it was like being in a cathedral. (Fig. 31)

Figure 28. Birds along window, Centre Pompidou

Figure 29. Birds along window, Centre Pompidou

Figure 30. Maïastras

Figure 31. Bird in Flight, dramatically placed in front of a red background

In 1913, Brancusi sent five sculptures to the "Armory Show” in New York. That exhibition was the beginning of his rise to fame in the U.S. In 1927, Brancusi sent a bronze Bird in Flight, to the U.S. As a work of art, of course. The US Customs Office refused that classification, calling it instead, an industrial part made of metal. The issue was taxation, of course. If it was art, no tax, if it was a metal industrial part, it was taxed at 40%. There was a court case, Brancusi won and coincidentally redefined art.

Smooth & Rough. Brancusi was as obsessed with the rough as he was with the smooth. Depending upon the material, of course. Marble and bronze “surfaces were painstakingly polished, all traces of technique erased.” While other surfaces were left unhewn or roughly hewn. Pedestals and plinths were another of Brancusi’s obsessions. He was as careful with them as he was with the sculptures. “Brancusi took great care with the plinths …” By focusing on them, “Brancusi questions their conventional status, traditionally used to elevate the sculpture and set it apart from its surroundings.” Sometimes he turned plinths into sculptures, thereby turning on its head the “notion of the top and the bottom, … the banal and the noble.” (Figs 32, 33)

Figure 32. Example of juxtaposition of Smooth and Rough

Figure 33. Another example of smooth with unhewn and roughly hewn

Reflection and Motion. Brancusi wrote that “We only see the reflections of real life.” By endlessly polishing bronze, the artist created “ shiny, mirror-like reflective surfaces” which he sometimes transformed into moving shapes by placing the works onto ball bearings and setting them in motion. (Fig 34)

Figure 34. Leda, 1920, moves round and round as if on a 78 rpm record

Animals: In the 1930s and 1940s, Brancusi developed two distinct animal series: 'volatile creatures’ (roosters, swans and other birds) and ‘aquatic creatures’ (fish, seals and turtles). (Figs 35, 36) The sculptures come in many versions, materials and formats. Yet they all seem “to obey the naturalist principle of the(ir) species.” By streamlining their shapes, Brancusi simultaneously “symbolize(d) the animal and capture(d) the way it moves.” According to Brancusi “When you see a fish, you don't contemplate its scales, do you? You admire its speed, the way its body slides and darts through water.”

Figure 35. Roosters three ways

Figure 36. Fish

The Base of the Sky: The final section celebrates Brancusi’s two monumental works. His first from 1926, the Endless Column created for his friend, the photographer Edward Steichen’s garden. (Figs 37, 38) Initially using a wooden plinth and repeating the same module, it was an evocation of funerary pillars from his native Romania. Ironically, Brancusi’s only monumental project was erected in his homeland, in Targu Jiu, 1937-1938. In cast metal, one mile long and nearly 100 feet high, Brancusi placed three symbolic elements: The Table of Silence, The Gate of the Kiss and the Endless Column. (Figs 39 - 41).

Figure 37. Endless Column installation in Edward Steichen’s French garden, 1926

Figure 38. Some endless columns upclose

Figure 39. Table of Silence, Targu Jiu, Romania, 1937-38

Figure 40. Gate of the Kiss, Targu Jiu, Romania, 1937-38

Figure 41. Endless Column, Targu Jiu, Romania, 1937-38

Conclusion: I often feel overfed, even slightly nauseous, at retrospectives. Sometimes too much of even a good thing is just too much. That didn’t happen with Brancusi. I could have kept looking at his work. Like the Picasso show at the Musée Picasso last year or the Sophie Calle show that followed it at the Musée Picasso. Which reminds me. After I saw the Brancusi exhibition the first time, I went to the bookshop and what should I see, and in English, a book about Sophie Calle that I had almost bought at her exhibition. I’ve left the price tag on so you can experience my pleasure, vicariously! (Fig 42) Gros bisous Dr. B.

Figure 42. Book I bought at bookshop, 6th floor, Centre Pompidou

Thanks so much to those of you who took the time to send a comment, they are very much appreciated. Gros bisous, Dr. B.

New comment on A week in the life …..:

Have you tried a Chicago Hot Dog? Worth trying.

A Chicago-style hot dog, Chicago Dog, or Chicago Red Hot is an all-beef frankfurter on a poppy seed bun, originating from the city of Chicago, Illinois. The hot dog is topped with yellow mustard, chopped white onions, bright green sweet pickle relish, a dill pickle spear, tomato slices or wedges, pickled sport peppers (a variety of Capsicum annuum), and a dash of celery salt. Ben, Baltimore

New comment on A week in the life …..:

Always enjoy your newsletter Dr. B.

Fun you made the rounds thru Port Arsenal where we have a bateau. We return to Paris in a few weeks. How was the Baguette? Excited to try Utopie. Happy USA Mother's Day to you. Nancy, Portland, OR et Paris Arsenal

New comment on Richard Serra: Steel Plated Tanker as Madeleine:

Hi Beverly,

Thank you once again for a wonderfully wrought weekly report on your culturally rich adventures in Paris or San Francisco, two cities that have been and continue to be foundational, though proportionally different, for me. Our interests and neighborhoods overlap, so I wouldn’t be surprised if I bumped into you one day when I’m out and about. In fact, the picture of you sitting in one of the artistic bench areas along the Coulée verte was immediately familiar since I walked by there just yesterday! I appreciate all the tips (lectures at the Mairie du 11eme, concerts at the Saint Louis en L’Ile church, all reminders of how I need to make more of an effort to attend). I love Brigat, too!

I’m divided on Serra’s sculpture and can understand that it would be off-putting for some. And on the subject of outdoor public sculptures, the bicycle pedal at La Villette happens to be part of a favorite—Claus Oldenburg’s Sunken Bicycle, maybe because of the subject, but mostly because of everything else it conjures about spaces, both real and imaginary. His Cupid’s Span along the waterfront in SF is another standout!

Merci encore et à bientôt, Susan

New comment on Giovanni Boldini: The Master of Swish:

Lord those portraits What panache! Would LOVE to be able to paint like Boldini. Juliet

Copyright © 2024 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you!