From iPads to Scrolls

Ma Normandie, David Hockney. Galerie Lelong, Paris

Figure 1. Exhibition poster, LeLong Galleries, Oct. 2020

There are some artists to whose work we are, each of us, immediately, viscerally, drawn. The artists aren’t the same for everyone, of course. For me, those artists include Matisse, Bonnard, Vuillard. I look at their paintings and I am visually sated. I don’t need to know if there is a story behind the paintings, I am not looking for iconography or history, I am transported by the beauty of the painted surface (of course I am delighted when there is a ‘backstory’ to learn about, as I did with Julia Frey’s book on Vuillard which I will be reviewing soon).

Likewise, I am drawn to David Hockney’s work and certainly the painting series he has just completed, ‘Ma Normandie,’ a sampling of which is currently on view at the Lelong Galleries in Paris.(Figure 2)

Figure 2. David Hockney, entrance to his17th century

Normandy home

Hockney found inspiration in the Bayeux tapestries, which are not far from Deauville, where I spent a little time last week. (Figure 3) Hockney is an art historian’s artist since his knowledge of and appreciation for the history of art is as broad as it is deep.

Figure 3. Bayeux Tapestry, Musee de la Tapisserie Bayeux

Hockney was born in England in 1937 and moved to Los Angeles when he was not yet 30. (Figure 4) He more or less captured and defined the LA lifestyle - slender men in pastel jackets and slacks; wide expanses of swimming pools filled with the bluest of chlorinated water. As Deborah Solomon so succinctly noted, “Hockney’s scenes of American leisure capture the eternal sunshine of the California mind with an incisiveness that perhaps only an expatriate (or Joan Didion) could muster.”

Figure 4. David Hockney as a young man

Fun fact, one of Hockney’s early paintings called Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures), (Figure 5) which he sold for $20,000 in 1972 through Andre Emmerich Gallery (and for which he probably received a lot less) sold at auction for $90.3 million two years ago. As Lawrence Weschler wrote in the Atlantic, “…(W)hen it comes to assigning a fair and just monetary value to a work of art, (that value) is somewhere between worthless and priceless”. According to Weschler, there are several levels of scandal operating when works of art are sold at such prices. Firstly, the bidders are all private (no museum could afford these prices), so once these works are sold, they disappear from public view; secondly, artists rarely profit from the increased value of their own work; and finally, how is it that so much money is in the hands of so few people while so many people, including those sleeping on heating grates outside galleries and auction houses, don’t have any money at all.

Figure 5. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with two figures) 1972

Alas, since we can’t cure any of life’s injusticesat the moment, let me tell you a few things about David Hockney that I especially admire. Hockney has been studying the art of the old masters for a long time, especially how artists like Jan van Eyck and Vermeer created pictures of intense realism. When I studied art history, it was explained to us this way. Jan van Eyck, an artist from Belgium, invented (rediscovered) the recipe for oil painting in the 1420s. (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Arnolfini Wedding, Jan van Eyck, 1434

That invention permitted van Eyck and his fellow northern European artists to depict scenes with such breath-taking detail that every flower and tree and bird can be identified. Italian painters, like Masaccio, who mostly painted frescoes, strove for naturalism in expression and gesture. (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Holy Trinity with Donors, Masaccio, 1428

The hallmark of Italian naturalism was the discovery (or rediscovery) by Brunelleschi (who built the Duomo on Sta Maria del Fiore) in Florence, of single point perspective. (Figure 8) This discovery allowed Italian artists to create three dimensional space on a flat, two dimensional surface.

Figure 8. Perspective studies. Filippo Brunelleschi

When the German artist Durer returned north from his trip to Italy, he brought back single point perspective and naturalism. After the Italians saw the Portinari Alterpiece by Hugo van der Goes (Figure 9) when it arrived in Florence, the Italians got realism.

Figure 9. Portinari Alterpiece, Hugo Van der Goes, 1475

David Hockney became obsessed with both - the incredible accuracy of the northern artists and the use of single point perspective by the Italian ones. Hockney’s obsession turned into a crusade. He began amassing photos of paintings from the 11th century onward, pinning them up in chronological order on a wall in his studio, which he called, his Great Wall. (Figure 10) Hockney saw a sudden rise of realism around 1420. That was the germ of what came to be called the 'Hockney–Falco Thesis’.

Figure 10. The Great Wall, David Hockney, 2000

Falco is Charles Falco, a physicist who simply stated the obvious, curved mirrors were available to scientists in the 15th century and they were available to artists, too. Their thesis contends that advances in realism and accuracy in Western art since the Renaissance “were primarily the result of optical instruments such as the camera obscura, camera lucida and curved mirrors.” (Figure 11)

A 2001 book by Hockney, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, and the BBC program that followed, visually demonstrated their argument: the level of accuracy in the work of the Old Masters was impossible by "eyeballing it” alone. Which is true, which I already knew from my art history classes.

Figure 11. Camera Lucida

I remember reading about their theory in the New Yorker. I never thought that they ‘discovered’ anything that hadn’t already been discussed. But they got a lot of pushback. Maybe what art historians objected to was the theory’s reductivism. They seem to be suggesting that with the right equipment, aka a curved mirror, (convex, concave, whatever) the right environment, aka a darkened space, the right equipment, aka paint brushes and paint, anyone could do it, like painting by numbers. In a way it confirmed the contention of the Ancients, that painting is a mechanical art, not a liberal art, that it requires skill, not intellect. Hey, come to think of it, that IS upsetting!

But this is even more upsetting. Tim Jenison, a computer graphics and 3D modeling software inventor and art enthusiast, spurred on by Hockney and Falco, and a book written by Philip Steadman, a British architecture professor, decided to prove that the 17th century Dutch artist, Johannes Vermeer used a camera obscura. The way he decided to prove it was to reproduce a painting by Vermeer, The Music Lesson, (Figure 12) using only techniques available to Vermeer. After seven months, Jenison had copied a Vermeer. (Figure 13) Steadman and Hockney felt vindicated, Vermeer had indeed used the same (or similar) tools to create his paintings. A film documenting Jenison’s experiment, directed by the magician Teller, called Tim’s Vermeer, came out in 2013. I saw it on my birthday that year.

Figure 12. The Music Lesson, Johannes Vermeer, 1665

Figure 13. Teller & Gillette and Tim Jenison & his Vermeer, 2001

Hockney is no fan of single point perspective. He prefers to play with perspective, shifting it and skewing it. He believes that the human eye is more fluid and dynamic than a single point of view. By employing multiple perspectives, which reflect the moving focus of the human eye, Hockney positions the viewer in the work rather than outside of it. (Figure 14)Hockney has begun exploring the concept of “reverse perspective,” based upon an essay of the same name, written in 1920, by a Russian mathematician and art historian who got caught up in one of Stalin’s purges. The essay contends that correct perspective is overrated.

Figure 14. Interior with Blue Terrace & Garden, David Hockney, 2017

The absence of perspective in Russian icons, Egyptian art and Chinese art, is not because those artists couldn’t master perspective but because they weren’t interested in it. I remember reading about Catholic missionaries, some of whom were artists, going to China and Japan in the 16th century. They demonstrated single point perspective to Japanese artists who happily began experimenting with it. The Chinese artists were indifferent, even hostile to what they perceived as a mere trick.

On the other hand, Hockney happily embraces technology. Maybe what art historians perceive as ‘outing’ his predecessors, that is, proving that they used the technologies of their time, was only a way of providing a context for his use of the technologies of our time. He has been sketching directly onto his computer since 1985. He has used an iPad to create New Yorker Magazine covers for years. (Figure 15)

Figure 15. The Road, David Hockney, 2018

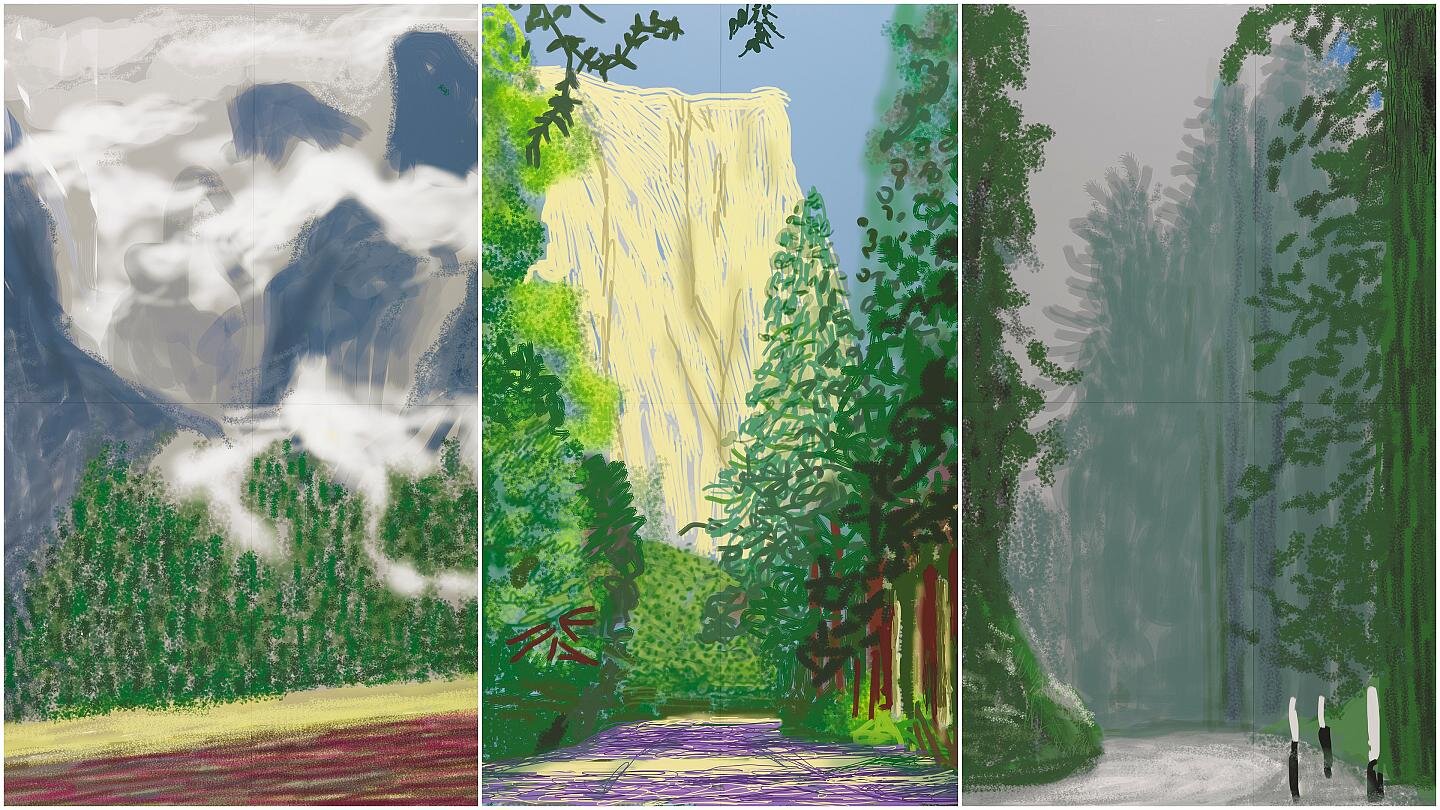

And for the past eleven years, Hockney has painted hundreds of portraits, still lifes and landscapes using an application for his iPhone and iPad called Brushes. Ten years ago, Hockney went to Yosemite National Park to draw landscapes with his iPad. (Figure 16)

Figure 16. Yosemite landscapes with iPad, David Hockney, 2011

He used an iPad to design the recently (2018) unveiled stained glass window at Westminster Abbey which celebrates Queen Elizabeth II’s reign. (Figure 17)

Figure 17. Queen’s window, iPad design, David Hockney, 2018

I saw an exhibition of this work at the De Young Museum in San Francisco. It was mesmerizing. (Figure 18) I sure can understand the appeal of moving to Yorkshire after years of season-less Southern California. One thing I missed most when I lived in San Francisco, where I moved after I returned from Australia was seasons. They just do not do deciduous trees there. Of course, balmy November weather was some compensation, but still, who doesn’t want it all.

Figure 18. Yorkshire, David Hockney, 2010-14

The seasons conspired to take Hockney away from southern California again in 2018, although the backstory for Hockney’s newest series of paintings, Ma Normandie (Figure 19) seems more whimsy than intent.

It happens that when he was in London for the dedication of that stained glass window, he decided he needed a break. So, he took off for Northern France, to Honfleur, for a few days of wandering in the footsteps of the Impressionists as I did last week. Hockney also wanted to visit the Bayeux tapestries, which he hadn’t seen since the 1960s, which I had never seen before.

Figure 19. Ma Normandie, Hockney, Pace Gallery, New York, 2019

Hockney decided that the 230-foot-long embroidered cloth had more in common with Chinese scroll painting than with Western image-making because it is ‘read’ in time and in sections—just like a scroll. It was while examining the Bayeux tapestry that Hockney’s next project was hatched. He would depict spring, not with multi-camera videos as he had in Yorkshire, but with a scroll like in Bayeux. The single image anyone who has taken Art History 101 has seen from the Bayeux Tapestry (actually it is really an embroidery) is Halleys Comet, which appeared in April, 1066. (Figure 20) Duke William of Normandy interpreted the appearance of the Comet as a good omen. The Pope had already given his blessings to invade England, so for William the Comet was God’s assurance that he was good to go, so he did.

Figure 20. Halleys Comet (in the sky) Bayeux Tapestry, 1070

If you haven’t seen the Bayeux Tapestries yet, it is definitely worth the trip to Bayeux. It is a lot of things, among them a rare example of secular Romanesque art (1000-1200) and a rare example of a very old piece of cloth. Tapestries and embroideries adorned churches and wealthy houses in medieval Western Europe, but fabric is fragile and the Bayeux tapestry is one of the very few to survive. What makes it even more exceptional is its size, 20 inches high and 224 feet long. Divided into three horizontal strips, the central panel is the largest and consists of seventy-five scenes depicting the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England and culminating with the Battle of Hastings in 1066. (Figure 21)

Figure 21. Battle scene with dead soldiers below,Bayeux Tapestry, 1070

The tapestry is a work of art of course, but it is also a chronicle of events and political propaganda, visual evidence of 11th century warfare and weaponry and documentation of numerous everyday objects.

I did mention that there were upper and lower strips/panels, too, right ? Well, the images embroidered on them are mostly playful, sometimes grim, for example, there are fabulous and familiar animals from Aesop's Fables and there are soldiers pulling the clothes from their fallen enemies’ (comrades?) bodies. And, every so often, some very weird sex scenes, which are pretty startling when you see them (not that this should be your motivation for going, but really, why not). (Figure 22)

Figure 22. Woman being punched by a priest, naked man below. BT, 1070

So, like I was saying, David Hockney visited Bayeux and those tapestries/embroideries inspired him to paint nature in a different way. And as one does, well, anyhow as Hockney did, he bought a house in Normandy to paint springtime like a scroll to be “read” in time and in sections. The house he bought is just outside Beuvron-en-Auge a village of 200 people. (Figure 23)

Figure 23. Beuvron-en-Auge, David Hockney, 2019

His house is a 17th-century half-timbered cottage surrounded by poplars and fruit trees; a small pond and a little river. An old cider-press just outside the house would become his studio. That was 2018. Hockney returned to Normandy in early March 2019. The new studio wasn’t ready but Hockney was. So he began filling an eight-inch-by-11-foot Japanese concertina sketchbook with a panoramic ink drawing of his new surroundings. Opening like an accordion, Hockney’s drawing makes a 360-degree circle around the house, ending where it began.

As Hockney says, he can paint the old houses of Normandy which the Impressionists did not want to paint, because to them, the houses were old fashioned and they wanted to paint what was new with their new style of painting. But 150 years after the first Impressionist exhibitions, Hockney doesn’t feel the same constraints. The houses are there, in much the same way as the landscape is there. He lives in one and is surrounded by the other. His Normandy paintings celebrate country life, which used to be old fashion but right now - who wants to live in a city?If you look Hockney’s painting of the Apple Tree, (Figure 24) the branches are like waves, the leaves on the branches like smaller waves. The chevrons of the sky repeat the pattern like the arabesques in Van Gogh’s Blue Self Portrait. (Figure 25) The parallel between Hockney and Van Gogh has often been noted and a dual exhibition at the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam confirmed it.

Figure 24. Apple Tree, David Hockney, 2019

Figure 25. Blue Self Portrait, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889

Let me end here with a few words from David Hockney which are found in the exhibition catalogue, they may be of some comfort to us now as we anticipate further restrictions on our movement, perhaps even another confinement.

“I have been working this year 2020, to depict the arrival of spring in Normandy. This takes about three months, and I think it’s the most exciting thing nature has to offer in this part of the world. So when the lockdown came, I didn’t mind. (Figure 26, Figure 27) I could concentrate on one thing. I did at least one drawing a day (using an iPad) with the constant changes going on.

Figure 26. Hockey in Confinement, 2020

Figure 27. Hockney now, smoking his 1 pack a day, in peace, in France

I kept drawing the winter trees, and then the small buds that became the blossom and then the full blossom. Eventually the blossom fell off, leaving a small fruit and leaves.” (Figures 28, 29, 30)

Figure 28. Trees in Mist, Hockney, iPad, 2020

Figure 29, Trees with less Mist, iPad, 2020

Figure 30. Ma Normandie, David Hockney, what exhibition poster based on

The process in reverse is what we are moving towards now, but still, I think we can learn from this to find pleasure in the small things. Nature keeps on going, even if our own animation is suspended.

Copyright © 2020 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved