Brave Kusama

Yayoi Kusama: The New York Years 1958 - 1973

Bienvenue and welcome back to Musée Musings, your idiosyncratic guide to Paris and art. When I first read about and saw photos of a Godzilla-like Yayoi Kusama hovering above the Louis Vuitton boutiques in Paris and New York and at Harrods in London (which LVMH doesn’t even own) and robot Kusamas painting dots in the windows of those same or other Louis Vuitton boutiques, I thought I would just rail against commercialism, show you a few photos and move on to something else, like art. (Figures 1, 2, 3)

Figure 1. Kusama painting dots at Louis Vuitton boutique, Paris

Figure 2. Kusama painting Louis Vuitton headquarters across from La Samaritaine

Figure 3. Kusama painting in a Louis Vuitton boutique window

Figure 3a. Video of Kusama robot painting.

But when I went to the boutiques in Paris last month to see the Kusamas and the dots for myself, I changed my mind. It was fun, it was joyful, it made everybody happy - taking photos of ourselves with the statue and the dots. Last week, Kusama Part 2 ‘dropped’ at Louis Vuitton headquarters across the street from La Samaritaine. Towering above everything is the same Kusama statue that is in front of Harrods. In both London and Paris, Kusama holds a paint brush in one hand and a handbag in the other. In London, the purse might be mistaken for an homage to the late queen, who was never without hers. In Paris, it looks like what it probably was always intended to be - creative product placement. Of a Kusama designed Vuitton purse.

Besides being fun, the statues of Kusama and the dots are about the artist and her art. Louis Vuitton has been collaborating with artists since 2001 when Marc Jacobs, then the company’s artistic director, came up with that brilliant and remunerative idea. Artists with whom the commercial arm of Vuitton collaborates, are showcased in exhibitions at the Fondation. Louis Vuitton collaborated with Kusama in 2012 and held an exhibition of her work at the Fondation a few years later. It was my first experience in one of her infinity rooms. It was red and white, I was wearing red and white. I didn’t know where the room stopped and I began. Very immersive, very impressive.

As I began exploring Kusama’s life and work, as I learned more about how she started and how she has endured for the past 80 or so years (she was born in 1929, she will be 94 on March 22), I began to have questions for which I wanted to try to find some answers. For example, she is a Japanese woman who was in New York in the 1960s so I wondered if she knew Yoko Ono (that sounds racist, sorry), (Figure 4) never imagining that I would be reading about Kusama and Georgia O’Keeffe. Then I thought about Damien Hirst’s Dots Series (Figure 5) and I wondered what Kusama thought about them since she has been painting dots for a very long time. I never imagined how many other ideas she has had over the years that have been appropriated by white, male artists.

Figure 4. Yoko Ono and Kusama in 2000

Figure 5. Damien Hirst in front of one of his Dot paintings

To begin. Yayoi Kusama was born in 1929, in rural Japan, into a wealthy family that owned plant nurseries. (Figure 6) When she was very young, Kusama started having hallucinations. It started this way, she was sitting with some flowers. (Which makes sense, she was living near a nursery.) All of the sudden, they began talking to her. As she remembers it (in a way that sounds very rational), “I had thought that only humans could speak, so I was surprised the violets were using words.…” She also experienced ”flashes of light, auras, … dense fields of dots.” She coped then and has coped ever since with patterns that multiply and flowers that talk, by drawing them in a sketchbook that she always carries with her.

Figure 6. Kusama as a young girl in Japan

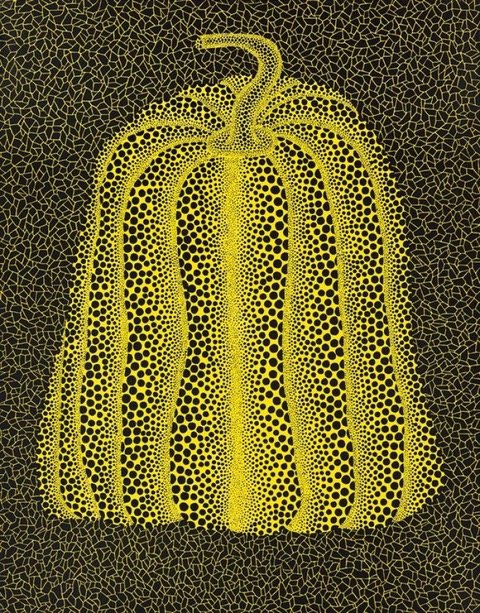

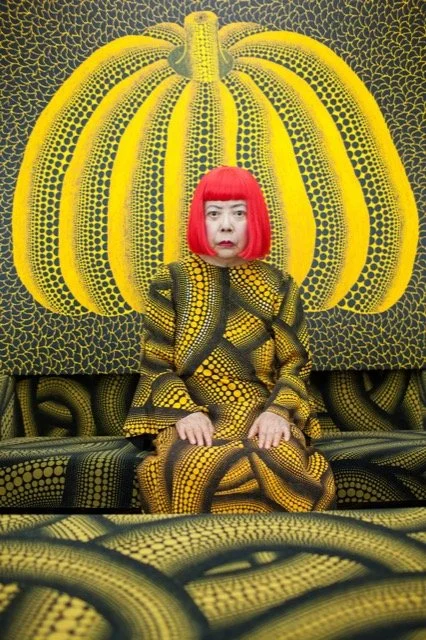

Flowers weren’t the only things that spoke to her. Pumpkins did, too. The first time she ran into a talking pumpkin, she was walking through a pumpkin patch with her grandfather. She picked up a pumpkin, it was the size of a man’s head. All of the sudden, it began chatting! She painted it and won a prize. She was 11. She still paints pumpkins and makes pumpkin sculptures, “I love pumpkins because of their humorous form, warm feeling, and a human-like quality.” (Figures 7, 8, 9)

Figure 7. Pumpkin painting, Kusama, 1981

Figure 8. Portrait of Kusama in front of painting of pumpkin

Figure 9. Portrait of Kusama with a sculpture pumpkin 2010

Talking plants and flashing dots seem a welcome relief from her other woes. Kusama’s father was a philanderer and his wife sent her daughter to spy on him and his mistresses. Then report back on what she saw. But when Kusama did, her mother would beat her, venting her rage on her daughter. Talk about shooting the messenger!

Kusama later explained how spying on her father has affected to her, "I don't like sex. I had an obsession with sex..… I didn't want to have sex with anyone for years …The sexual obsession and fear of sex sit side by side in me."

And beyond all that, (as if that wasn’t enough) her mother did everything she could to keep Kusama from becoming an artist. She wanted the kind of daughter who would become a proper wife and mother and who would lead a conventional life. Kusama’s mother destroyed her paintings and threw away her paint supplies. Hallucinations may have been a way to escape the horrors of her home life, too.

In 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese school children were conscripted to work in military factories. Kusama, who was 12 in 1941, worked six days a week for four years sewing parachutes for Japanese pilots. Working in a barely lit space (so American fighter planes wouldn’t see it and bomb it) must have been terrible. The deafening noise of planes flying overhead and the sound of non stop air-raid sirens, must have taken their toll, too.

After the war, Kusama began taking painting classes in Japan. But she wasn’t interested in traditional Japanese painting. She wanted to study contemporary, avant-garde European and American painting. “For art like mine, (Japan) was too small, too servile, too feudalistic, and too scornful of women. My art needed a more unlimited freedom, and a wider world.”

One day, Kusama was in a bookstore, looking through a book on American painters. One of painters was Georgia O’Keeffe. It was a revelation for Kusama. Perhaps, she thought, women painters could be successful in America. Kusama wrote a letter to O’Keeffe, asking for advice. O’Keeffe wrote back. She encouraged Kusama to try her luck in New York, warning her that it would be difficult. (Figure 10)

Figure 10. Letter from Georgia O’Keeffe to Kusama, 1955

Kusama arrived in the United States in 1958. She was 29 years old. The 1950s was no decade for independent women. Being an ambitious woman was bad enough, being Japanese made it worse. The internment camps in which the American government had imprisoned Japanese Americans from 1942 to 1945, was still part of America’s collective memory. Kusama didn’t have much money when she arrived. But she did have a trunk full of kimonos which she sold when she needed funds and in which she wandered the streets when she needed attention. (Figure 11)

Figure 11. Kusama in a Kimono, New York, 1960s

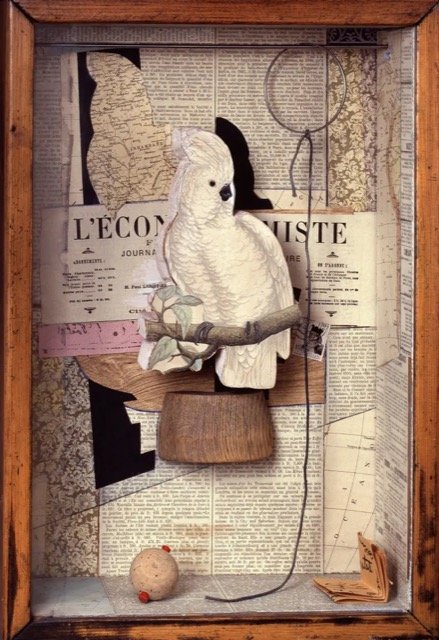

Kusama was in America, mostly New York, for 15 years, from 1958 until 1973. She experimented with all the ‘isms’ and a few other things, too - from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art; Minimalism to Happenings. She staged and participated in anti-war protests. She painted, sculpted and designed clothes. She hung out with Donald Judd and knew Andy Warhol. She developed a close, platonic relationship with Joseph Cornell the shy, reclusive artist known for his ‘Cornell boxes’ (Figures 12, 13)

Figure 12. Kusama and Joseph Cornell, 1970

Figure 13. Cornell Box, Joseph Cornell

Kusama wanted to become famous. But the cards were stacked against her. Art (and everything else in the 1950s) was a white man’s game. Of course she wasn’t the only woman who was ignored, or worse, both artistically and professionally. But here are a few of the most egregious examples of how white male artists stole ideas from her and then got credit for those ideas. Which should come as no surprise, histories of art were written by men about men.

In June 1962, Kusama was the only woman (and only person of color) who participated in a group show with Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol and others. Her piece, Accumulation 1, (Figure 14) is an armchair covered with variously sized soft, painted tentacles. Each was sewn before being stuffed and painted. All that sewing was not a challenge for Kusama, after all, she had spent 4 years sewing parachutes. Actually the protrusions that Kusama attached to the chair were not tentacles, they were phalluses. Kusama explained In her 2002 autobiography that those phalluses were a form of “self-therapy.” They helped her confront her fear and "disgust of sex”. Having spied on her father during his dalliances and having presumably witnessed a penis both erect and otherwise, she must have decided that the flaccid version was easier to control.

Figure 14. Accumulation I, Kusama, 1962

Her armchair intrigued both audiences and artists. Within months, Claes Oldenburg, whose work before the exhibition had been in ceramic and plastered burlap, began creating ‘soft sculptures,’ entirely of fabric. (Figure 15) The original idea for which he, rather than Kusama, has been credited.

Figure 15. Floor Burger, Claes Oldenburg, 1962

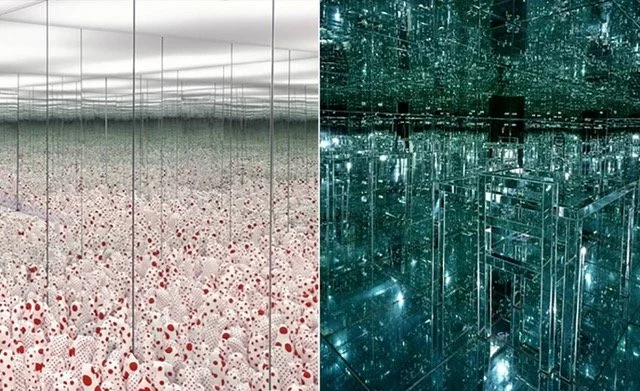

Similarly, a few months after seeing Kusama’s first Infinity Mirror Room, Phalli’s Field (Figure 16, 1965), Lucas Samaras jumped from small assemblage boxes to large, mirrored ones. (Figure 17) And once again, Kusama’s originality was appropriated by a male artist.

Figure 16. Infinity Mirror Room, Phalli’s Field, Kusama, 1965

Figure 17. Kusama, left; Lucas Samaras Infinity Box, right, 1966

And then there was Andy Warhol whose repeating cow wallpaper was such a hit in 1966. (Figure 18) He is credited with the repetition concept when in fact Kusama had created it two years earlier, with her One Thousand Boats exhibition. (Figure 19)

Figure 18. Repeating Cow Wallpaper, Andy Warhol, 1966

Figure 19. One Thousand Boats, Kusama, 1963

Heather Lenz, an art historian and film maker spent years trying to get funding for a film on Kusama. In 2018 she finally made her film in which she exposes these appropriations. According to Lenz, “Every single Q&A I do I get a question about how much the allegations that these white male artists stole her ideas were true. Obviously I checked all the dates and they all work out. People who had degrees in art history still challenged this though; it was as if they don’t want to shift their views. They know what they know, I guess.”

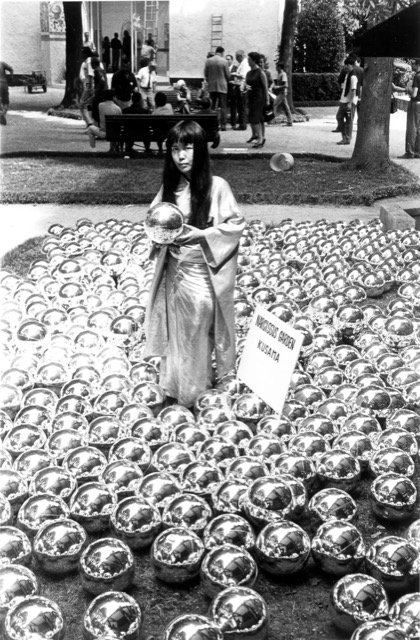

Here’s something fun. In 1966, Kusama went to the 33rd Venice Biennale. She wasn’t invited, she didn’t represent any country. But she organized a piece that covered the lawn near the Italian pavilion. Called Narcissus Garden, it was a field of 1,500 hand sized plastic reflective balls. (Figures 20, 21) Kusama sold the balls for $2 each. The Biennale authorities closed Kusama’s performance down, claiming that she was “selling art like hot dogs or ice-cream cones”. But commercialism at the Biennale was her point, that’s what she was opposing!

Figure 20. Narcissus Garden, Kusama, Venice Biennale, 1966

Figure 21. Narcissus Garden, Kusama, Venice Biennale, 1966

In the 1960s too, during the Vietnam War, Kusama staged happenings in New York. Her first Anatomic Explosion featuring naked dancers took place in October 1968 across from the New York Stock Exchange. (Figure 22) The artist's press release stated, ‘The money made with this stock is enabling the war to continue. We protest this cruel, greedy instrument of the war establishment.’

Figure 22. Anatomical Explosion, Kusama, October 1968

Kusama also began designing fashions in the late 1960s. She designed clothes with holes that revealed breasts or buttocks or genitalia. (Figure 23) In 1968, she designed a dress for two for her Homosexual Wedding performance. There’s a photo of John Lennon and Yoko Ono wearing one. (Figure 24) Kusama and Ono knew one another, they both created ‘Happenings’ and may even have been roommates for a short time. Kusama also designed an ‘orgy’ outfit which could accommodate several people at once. And what did Kusama design for herself? A bright pink Phallic Dress decorated with stuffed phalluses.(Figure 25)

Figure 23. Photo of Kusama making finishing touches on a dress design

Figure 24. Photo of Yoko Ono and John Lennon in a Kusama garment for two, 1969

Figure 25. Pink Phallus Dress, Kusama

Her stay in New York was difficult, she was often broke. She sometimes had to scavenge for food, dumpster diving for discarded scraps, like fish heads from behind the fish shop that she boiled for soup.

One story in her autobiography made me think of William Steig’s tale, ‘Brave Irene’ which I often read to my daughter. Kusama writes, “One day, I carried a canvas taller than myself 40 blocks through the streets of Manhattan to submit it for consideration at the Whitney Annual. My painting was not selected and I had to carry it 40 blocks back again.” “More than once,” Kusama writes, “it seemed as if the canvas would sail up into the air, taking me with it.” (Figure 26) To me, it was the same as when Irene, that cold and windy night, clutched the box with the duchess’s dress in it. (Figure 27) A sudden gust of wind blew the box out of Irene’s hands, into the air and onto a tree. As Kusama made her way back from the Whitney, the same thing nearly happened to her.

Figure 26. Photo of Kusama painting one of her huge paintings, 1961

Figure 27. Brave Irene, William Steig

After 15 years in New York, Kusama was ready to leave. She had worked too hard and earned too little. When her dear companion, Joseph Cornell, died in 1972, she was alone and exhausted. Kusama returned to Japan the following year. She was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive neurosis in 1977. She checked herself into a psychiatric hospital where she has lived, by choice, ever since. Next Week: Part II: Kusama: From Surviving to Thriving.

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.