The sculptor of the Essence

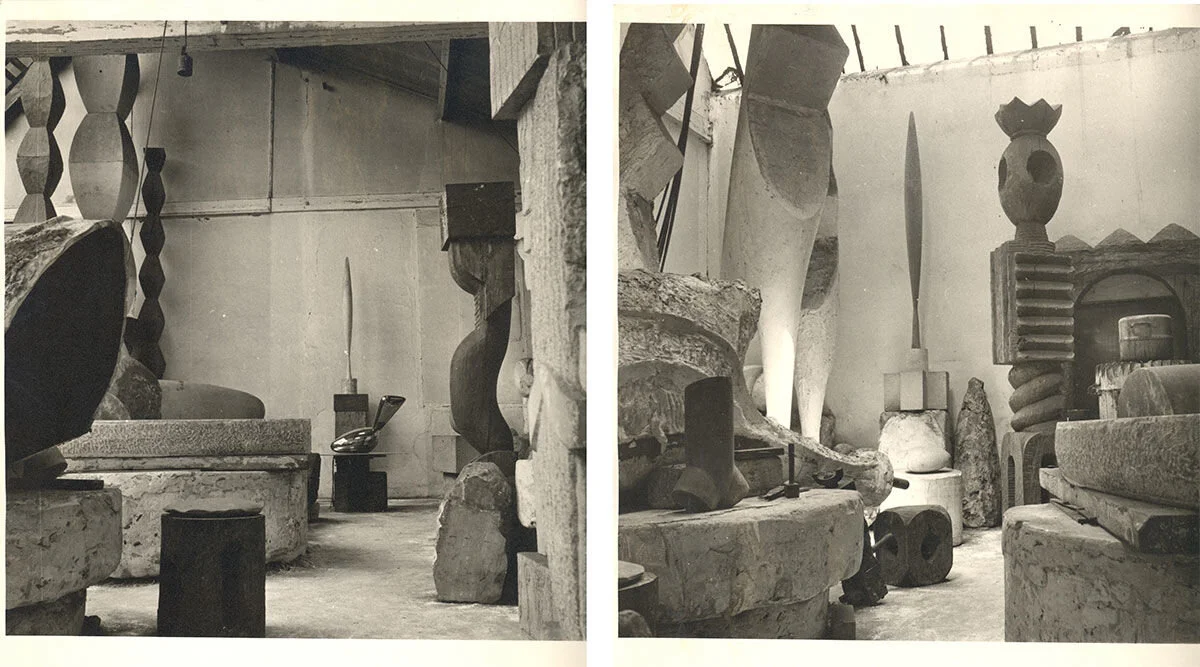

Atelier Brancusi

Figure 1 Atelier Brancusi, Centre Pompidou

I am going to talk to you about Constantin Brancusi today but I am going to start with a couple thoughts about two sculptors we have already discussed, Alberto Giacometti and Antoine Bourdelle. When I wrote about the Giacometti Institut a couple weeks ago, I told you that the very first thing you will see when you enter this little museum is a recreation of Giacometti’s studio, his atelier. Looking at it will surely be a feast for your eyes, it was for mine. I loved seeing all that clutter, all that stuff. I couldn’t live like that, I surely couldn’t work in that environment, I have more of a Marie Kondo kind of sensibility, keep it neat, keep it clean, keep it spare. But I really enjoyed seeing all of those strung out statues and statuettes. I liked the drawings all over the walls and the furniture, especially that bed. According to the Institut website, Giacometti’s studio gradually became an extension of himself and his life in Montparnasse. The drawings on the walls trace the artist’s development and provide important clues to his creative process. In the recreation of his tiny studio, there are over 70 sculptures, including the very last ones on which he was working at his death. The designers recreated the space using photographs, some taken by legendary photographers like Gordon Parks and Robert Doisneau. (Figure 2, Figure 3)

Figure 2. Giacometti in his studio

Figure 3. Recreation of Giacometti’s Studio at Giacometti Institut

With the pleasure of that visit in mind, I thought it would be good for us to wander over to the Marais, to the Centre de Pompidou, where the recreation of another sculptor’s studio can be found, that of Constantin Brancusi. (see above) Since it is free and since it is free-standing, I visit it every time I am in the neighborhood. Brancusi will be the fourth sculptor we will talk about who fell into or near the orbit of the 19th century legend, giant, larger than life kind of guy - Auguste Rodin. Antoine Bourdelle was the first and I should have been kinder to him in my review of the Bourdelle Museum a few weeks ago.

After all, he was an important figure in the Art Deco move-ment. When I look at his work, especially at the Theatre des Champs Elysees, (Figure 4) I get the feeling that those art deco motifs and statues are escapees from Rockefeller Center.(Figure 5)

Figure 4. Frieze, Bourdelle, 1910 Theatre des Champs Elysees, Paris

Figure 5. Friendship between France & America, Alfred Janniot, 1934 Rockefeller Center, NYC.

Bourdelle eventually did strike out on his own and is rightly celebrated for his instrumental role in the transition from the Beaux-Arts to modern art. As proof of his continued popularity in Paris, you need go no further than the Musee d’Orsay to find his work, Herakles the Archer, on permanent display.(Figure 6) Ossip Zadkine was influenced by Rodin and Giacometti studied under Bourdelle.

Figure 6. Herakles the Archer, Bourdelle, Musee d’Orsay

Finally Brancusi, about whom we are going to speak today, arrived in Paris in 1902 (Figure 7) and was almost immediately invited to join Rodin’s studio. We’ll get to that in a minute. But first, biography. Constantin Brancusi was born in Romania in 1876 to peasants whose back breaking work was all their son knew. At 7, Constatin was herding the family’s flock of sheep. At 9, traumatized by the brutality of his father and older brothers, he escaped his family and his village by walking to the nearest town and finding work, first at a grocer and then at a bar. Just before he turned 18, a wealthy industrialist noticed his talent for carving. And in a single stroke of luck, to be seen by the right person at the right time, the trajectory of his life changed. The industrialist paid for him to attend an arts and crafts school from which he graduated four years later. At 9 he had walked away from his family and village, now at 27, he walked toward his future, to Paris. Soon he was invited to join Rodin’s studio. After a month or two, reports vary, Brancusi left, explaining years later that “Nothing can grow under big trees.” Better, Brancusi thought, to struggle on his own than be eclipsed by Rodin’s shadow.

Figure 7. Brancusi as a young man

I love Brancusi’s work. Just as I adore Giacometti’s strung out statues and statuettes of men and women, I love how Brancusi always sought the essence, never the over statement. When I taught Italian Renaissance art history at Stanford, I started the course, of course with the proto Renaissance, with Giotto. I would take forever talking about Giotto’s frescoes at the Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel in Padua, which recounts the life of the Virgin and the life and death of her son, Jesus. One of my favorite panels is Joachim and Anna (Virgin Mary’s parents) embracing at the Golden Gate. (Figure 8, Figure 9)

Figure 8. Joachim & Anna embracing, Giotto, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1305

Figure 9. Joachim & Anna, Giotto, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1305, detail

I would compare it to ‘The Kiss' by Brancusi, (Figure 10) the pared down essence of the thing and contrast it with the overstatement, ‘The Kiss’ by Rodin. (Figure 11) It was a little tricky since the pre-eminent Rodin scholar was a colleague and there is a Rodin sculpture garden on Stanford’s campus. But I did it, what the hell. Never mind. Where was I ?

Figure 10. The Kiss, Brancusi, 1907

Figure 11. The Kiss, Rodin, 1882

Barely a decade after he arrived in Paris, in 1913, his work was displayed at the Salon des Indepéndents in Paris and at the Armory Show in the U.S., the country’s first modern art exhibition. For over 50 years, from the age of 27 until his death at 81, Brancusi lived in Paris, but he believed that he owed his career to collectors in the United States. ”Without the Americans,” he once said ”I could never have produced all that, nor even perhaps have existed," He reminisced about coming to America for the first time in 1926, "When I approached New York on the boat, I had the impression of seeing my studio on a large scale.” Skyscrapers along the horizon in real life must have seemed like Brobdingnagian versions of his iconic Endless Columns, a form he began experimenting with in 1918. (Figure 12)

Figure 12. Endless Column,

Brancusi, 1918

Two years after his own trip to New York, his iconic (am I using that word too much?) ‘Bird in Space’ (Figure 13) made the voyage, to be included in an art gallery exhibition curated by his friend, Marcel Duchamp. But something happened at US Customs. Although the law permitted artworks, including sculpture, to enter the U.S. duty free, when ‘Bird’ arrived, officials said it wasn’t sculpture, it wasn’t art. To qualify as sculpture, works had to be “reproductions by carving or casting, imitations of natural objects, chiefly the human form”. Because ‘Bird in Space’ did not look like a bird, officials classified it as a utilitarian object (“Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Supplies”) and levied a tax of 40% of the work’s value on it to clear customs

Figure 13. Bird in Space, Brancusi, 1928

Brancusi launched a complaint. He had two choices, either try to prove that his sculpture fitted the court’s definition of art or try to prove that the court’s definition of art was inadequate. He and his friends opted for the second path and the trial focused on defining art. Sounds like the 1960s Supreme Court debate about pornography, “I know it when I see it”. As inadequate for defining art as for defining pornography. The sculpture’s owner, photographer Edward Steichen and the British sculptor Jacob Epstein, among others, all testified that 'Bird in Space’ was art. The court was persuaded that its own definition of art was obsolete and while the object in question didn’t resemble a bird, the judge conceded that it might be considered “art” all the same.

How did Brancusi work ? While Rodin and others modeled clay and cast bronze. Brancusi carved sandstone, travertine and marble. (Figure 14) In this he resembled Michelangelo who contended that as a sculptor, he freed the form from the block of marble. (Figure 15)

Figure 14. Brancusi in his studio carving an Endless Column

Figure 15. Unfinished Atlas Slave, Michelangelo, 1525-30

Brancusi focused on a limited number of shapes and themes and continued to refine them over the years, polishing his sculptures until they gleamed. Brancusi began thinking that the whole was more important than its parts - that the pedestals upon which his sculptures rested were works of art, that the relationship between his sculptures and between them and the space they occupied, was significant. In the 1920s, his studio in Montparnasse on Impasse Ronsin became both exhibition space and work of art. Eventually Brancusi stopped creating sculptures, focusing instead on their relationship with one another and within the studio. (Figure 16) He no longer wanted to exhibit, he didn’t even want to sell anything. And when he did sell a sculpture, he replaced it with a plaster copy so that the unity and harmony of the studio as work of art was not disturbed. (Figure 17)

Figure 16. Brancusi’s Studio at Impasse Ronsin

Figure 17. Brancusi’s Studio recreated at Centre de Pompidou

As he entered the final decade of his life, (Figure 18) Brancusi began thinking about preserving his studio and so he bequeathed it and its contents: sculptures and sketches, furniture and tools, books and photographs, to the French state on the condition that it would be preserved in its entirety. According to an artist who had a studio nearby, Brancusi promised the other artists who lived on Impasse Ronsin that they would be allowed to remain there after his death. “He thought the City of Paris would make an enclave with all the old studios, but it was not made clear in his will that they would have to stay.

Figure 18. Brancusi, undated photo

So of course after he died they just moved it elsewhere.”, The present reconstruction was built by the architect who designed the Centre Pompidou in front of which Brancusi’s studio sits, Renzo Piano. It is not an exact replica of Brancusi’s studio but it is a quiet, reflective, interior space, physically separated from the lively museum in front of which it sits and the crowds always mulling about in the piazza it occupies. (Figure 19)

Figure 19. Exterior of Brancusi Studio,

Centre de Pompidou