A Little Gallerist with Big Ideas

Berthe Weill and Avant-Garde Art

Berthe Weill and Mrs. Bollag, Moira Kalen, 2019

I read an article the other day in the online publication ArtNet, about the contemporary art scene in Paris, the art scene that I have been talking about for the past couple of weeks. The art of RIGHT NOW. The article begins with a reference to the art scene of a century ago. “In the 1920s, Paris was an art market center. Dealers on the Left Bank were known for nurturing adventurous new talent, with Léonce Roseberg (sic) showing Georges Braque and Fernand Léger, while Paul Guillaume was promoting Derain and Matisse.”

Figure 1. 21 Rue La Boetie, exhibition 2017, Musée Maillol, Paris

It is true that these two art dealers were among the first to show the new art of the time. They were joined by others, including Léonce Rosenberg’s brother, Paul whose gallery at 21 Rue Boétie was the subject of an exhibition (Figure 1) at the Musée Maillol (note to self, write a review about Maillol and his museum). That exhibition was based on the biography of Rosenberg written by his granddaughter on her mother’s side, Anne Sinclair. Her name is probably familiar to you because she was married to the man who got this whole #me too thing started, Dominic Strauss-Kahn. His scandalous behavior went public before the behavior of America’s own home grown sexual predators, Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer, etc. did. When those two gents and others like them (I’m looking at you, Charlie Rose) were nothing more than living nightmares to most of the young women who worked for them.

But let’s go back to the 1920s, to a less fraught time. When sexism and misogyny were just the way things were. When harass was spelled her ass (thank you, Katie Couric). And the first art dealer to display ‘young art,’ avant garde art, wasn’t a man at all but the woman I am going to tell you about today.

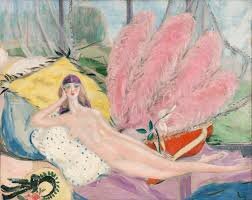

Figure 2. Nude, Jacqueline Marval, 1920

I have been writing a fair amount about female artists during the last year because the subject interests me and because, in this @metoo moment in our collective lives, there have been quite a few exhibitions to write about. There were exhibitions on the sculptor Kiki Smith, the photographer Sarah Moon and the architect Charlotte Perriand. There were also female artists I wasn’t expecting to find, like Ossip Zadkine’s wife Valentine Prax and more recently the painter, Jacqueline Marval. (Figure 2)

Figure 3. Portrait of Berthe Weill, Georges Kars, 1933

It was when I was writing about Jacqueline Marval that I stumbled upon a female gallery owner, Berthe Weill. (Figure 3) I told you a little bit about her, but now I want to tell you a little more because everything about her seems so improbable. And because while the Rosenbergs and Paul Guillaume and the other male gallery owners / art dealers are well known, her accomplishments were neither remembered nor acknowledged until recently and only because an art history student (now Ph.D.) Marianne Le Moran, read her name and wanted to know more, then found more and is now the founding director of the Berthe Weill archives. (bertheweill.com)

Figure 4. Moulin de la Galette, Pablo Picasso, 1900

Figure 5. Eiffel Tower, Diego Rivera, 1914

Here are a few reasons that Weill is so important. She was the first gallery owner to sell a Picasso. (Figure 4) The first gallery owner to show Matisse and fellow Fauves. The only gallery owner to give the Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani a one man show during his lifetime. And the only one to give the Mexican artist, Diego Rivera a show during the decade he lived in Paris. (Figure 5) And mid-career, she began to highlight women artists, like the aforementioned Jacqueline Marval and Valentine Prax as well as Suzanne Valadon and Marie Laurencin.(Figure 6, Figure 7)

Figure 6. Drawing dedicated to Berthe Weill, Suzanne Valadon, 1895

Figure 7. Portrait of Mlle Chanel, Marie Laurencin, 1923

Berthe Weill was born in Paris in 1865, one of seven children born into a poor Jewish family. She and her siblings were each given a ‘Jewish’ (Old Testament) name and a less ethnically specific ‘French’ name. I am sure you know that until 1993, France had a list of acceptable prenoms from which a parent could select a name for their new born son or daughter. I used to think that list was outrageous but I’m not so sure now. My daughter suffered for years because I gave her the name of Leonardo’s only painting in North America, Ginevra. Nobody in Australia or the USA ever heard of that name, nobody knew how to pronounce it. For the impact names can have on one’s life, I direct you to the 2013 Freakanomics podcast, How Much Does Your Name Matter.

Figure 8. French Chiffonier (Ragpicker) Eugene Atget, 1899-1901

Berthe’s ‘OT’ name was Esther (shout out to Queen Esther of Purim fame, celebrated last week). Like Bernard Berenson’s father, like Kirk Douglas’s father, Berthe Weill’s father was a ragpicker, (Figure 8)That was an actual job and in Paris, ragpickers were regulated (of course they were, France was, still most certainly is, a country of regulations). They could only work at certain times of night and they were supposed to return anything of value they found, either to its owner or to the authorities. (yeh, right) When I lived in the moribund 16th arrondissement, I lived right down the street from rue Eugène Poubelle, who gave his name to what he is most identified with (think Thomas Crapper and the flush toilet), the garbage can. Poubelle was criticized for bringing an end to the job of ragpicker. Ragpicking may no longer be a job in Europe or America, collecting cans seems to have replaced it, but it is still a job in India.

Berthe completed grammar school, but in a family with so many children and so little money, more schooling was out of the question and she was apprenticed. Being a sickly child, physical labor wasn’t an option (lucky girl) so she went to work for a distant cousin, a prints and curiosities dealer. She worked with him for nearly 20 years. When he died in 1897, Berthe continued working at the shop.

Figure 9. Portrait of Berthe Weill, Emilie Charmy, 1920

Wait, am I missing something? Where’s the husband? Why didn’t Berthe do what most young women who had to work, did, still do - work for a few years, in her case from the age of 10 to 18 or 19 and then get married. Why was she still working for her cousin 20 years after she was first apprenticed to him. Seems that little Berthe, (she was only 4’9” tall), (Figure 9) didn’t want to become somebody’s wife. She did not want her salary to be the property of some man. No, she had no intention of sacrificing her independence. She wanted to do what she wanted to do and that included spending the money she had been given for a dowry, to stay in business.

Figure 10. Portrait of Pedro Meñach, Pablo Picasso, 1901

After her cousin’s death, she went into partnership with one of her brothers, a short lived mistake. The year that association ended, 1901, she met a young industrialist / art dealer from Catalan, Pedro Mañach (Figure 10) who was supporting and promoting a group of young Spanish artists , one of whom was Pablo Picasso. Mañach asked Berthe if she wanted to change the nature of what she was doing and begin exhibiting the work of young painters. In fact, that is exactly what she wanted to do. So, with Mañach, she transformed her little boutique into an art gallery, ‘Galerie B. Weill’. What option besides hiding the fact that one is a woman, did a woman have? Think George Sand and George Eliot or more recently, the initials only mystery writer P.D. James.

The inaugural exhibition was held on December 1, 1901. A young illustrator, Lobel-Riche created a card for the opening, on which was written “Place aux jeunes! “ proclaiming that this new gallery would specialize in paintings by young artists. The exhibition brought lots of interest but very few sales. Mañach and Weill decided to alternate exhibitions of young artists with exhibitions of satirical cartoonists, for which there was a ready market and which could make up for the new art that didn’t sell. Unfortunately, Mañach’s association with Weill lasted only a few months. According to Weill, in her 1933 autobiography, Pan dans l’oeil, “Mañach being called to Spain for family matters, I must … assume the heavy task of continuing the work he has set up so well. Thanks to him, artists will henceforth know the way to my gallery, which allows me to regularly exhibit the paintings of all these “Young people” whose number is always increasing.”

Whether Mañach and Weill had any sort of personal relationship, I don’t know. Whether he was called back to Spain by a wife or whether he was encouraged to leave by French authorities who had a file on him as well as fellow anarchist, Picasso, I don’t know. Picasso’s police file includes the following snippet, “Picasso shares the ideas of his compatriot Mañach, consequently, he should be considered an anarchist.” Okay, so much for evidence. But even if one does not read too much or indeed anything, into it, Mañach’s return to Spain was a real loss for Weill. They were both passionate about contemporary art. His skill set included a head for business, hers did not. If he hadn’t left, she might have lived a very different life. But he did and she didn’t and this is her story. (Figure 11)

Figure 11. Caricature of ‘Mere Weill’ surrounded by Chagall, Vlaminck, Picasso, Leger, Braque, by Cesar Abin,1932

In addition to selling Picasso’s first paintings, she gave Matisse and other Fauves a show before they were ‘discovered’ at the Salon d’Automne in1905. Again, from her autobiography, Leo and Gertrude Stein were interested in Matisse, but, “ they didn’t dare buy his work, ’Believe me, buy Matisse,’ I told them.” The Steins did eventually buy Matisse, indeed they became major Matisse collectors, but not until he changed galleries. Was it timing or was it Weill? Or more specifically was it Weill and Stein. That’s Marianne’s guess. Two very short Jewish women with two very strong personalities. Who knows. (Figure 12, Figure 13)

Figure 12. Portrait of Berthe Weill, Pablo Picasso, 1920

Figure 13. Portrait of Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso, 1905-6

Figure 14. Invitation to Modigliani exhibition, 1917

Weill’s show for the Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani in 1917 was a true drame. (Figure 14) For the opening of the exhibition, she put one of the artist’s paintings in the window. As one does. It was a nude. (Figure 15) Again, Weill’s autobiography, “There was a police commissioner living opposite the gallery who saw that the crowds were arriving. They could see one of Modigliani’s nudes from the window. …The painting (the police told her) had to be taken away.” Tiny Berthe Weill stood her ground and refused. The officers dragged her to the police station.

Figure 15. Nude, Amadeo Modigliani, 1917

But what was the issue? Nudes have been a mainstay of European art for a very long time. The Greeks depicted goddesses nude and so did Renaissance painters and sculptors. Manet’s painting Dejeuner sur l’herbe’ was shocking not because they were nude but because they were prostitutes, not goddesses. But all those nudes followed one convention, had one thing in common. They were epilated. Not one of them had pubic hair. (Figure 16) Modigliani’s nude had, according to one policeman, ‘fur’. If Weill hadn’t finally removed the painting from view, she would have been prosecuted for her "insult to modesty.”

Figure 16. Girl with Dog, Fragonard, 1770

You may now be thinking about another canvas, Courbet’s ‘L’origin du Monde,’ (google it) painted in 1866, nearly 50 years before Modigliani’s nudes. The difference? Courbet’s painting was a private commission, for an Ottoman diplomat, of his mistress, for his own personal, private, erotica collection. Lots of artists painted erotica, either on commission, as Courbet did, or for themselves, but not for display in a gallery window for anyone to see!

Figure 17. Invitation to exhibition for Flandrin, Marquet, Marval & Matisse at Galerie B Weill, 1902

Berthe Weill devoted her entire career to discovering and nurturing artists. (Figure 17) Her risk-taking was admirable, but not remunerative. There simply wasn’t a thriving market for artists who were just starting out, or for the women artists Weill increasingly began to show at her gallery. And the painters Weill did manage to sell didn’t stay with her long. As they became better known, thanks in no small measure to the gallery shows she held for them, they left her for the stability of contracts and stipends with established dealers like Ambroise Vollard, Paul Guillaume and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler.

Have you ever heard of Kahnweiler? As a German national, when the ‘Great War’ began, the paintings in his gallery were seized and sold by the French government. Between the wars, he reestablished his gallery, only to be forced into hiding in 1940 when the Nazis invaded France. He lived until 1979, so his reputation as a dealer and scholar were not forgotten. Paul Rosenberg had anticipated the Nazi arrival in Paris and was already in New York before the Nazis took over his gallery on rue Boétie and stole 400 paintings (all but 60 of which his family has tracked down). Like the Rosenbergs and Kahnweiler, Berthe Weil was a victim of anti-Semitism. She was forced to close her gallery in 1940 and go into hiding during World War II.

Being victimized for one’s religion is horrific. But Berthe Weill suffered her entire career from something her Jewish male compatriots never did: the pervasive misogyny that was France. Apparently, during the interwar period, her gallery, like Kahnweiler’s, became profitable. But at exactly the same time, she began to have problems with the tax authorities because of the misogyny inherent in French law, inherent in French bureacuracy. For example, women could own businesses but they couldn’t have a bank account without their husband's permission. Which is a little tricky if you are not married and own a business. Women weren’t trusted by banks, weren’t trusted by the French administration and most cruelly of all, Weill seems not to have been trusted by the collectors who were buying art. Is that why Gertrude Stein and her brother waited until Matisse left Weill for a male owned gallery?

Marianne told me about one particularly infuriating tax agent with whom Weill had to deal. He insisted that she have a tape measure in her shop. But why? She did not sell picture frames and she did not sell paintings by the centimeter. But the agent threatened her and the result was that she had to pay an annual tax on that meter which hung, unused and useless in her gallery.

Anti-semitism and misogyny took their toll, of course. But still, couldn’t Weill have better capitalized on her prescient taste in art. According to Marianne, it wasn’t because Weill couldn’t run a profitable business, it was because she chose not to. She had learned good business practices from working with her cousin and from working with Mañach but Weill’s focus was on supporting and protecting her artists, usually to her own financial detriment.

Figure 18. Benefit for Berthe Weill, 1946

According to Marianne, Weill considered herself as much an arts patron as an arts merchant. As a woman who has supported her own family, Weill’s years of magical thinking sound more like a woman with an inheritance or a woman with a husband paying the bills. When I lived in Pacific Heights, I remember walking along Sacramento St, past ribbon shops, candle shops, seasonal Christmas ornament shops. Tax write-offs for wealthy businessmen, not serious employment for their cosseted wives. But Weill didn’t have a back-up or a back-up plan. She was always generous, sharing food with artists when she was virtually starving herself. And in the end, her artists didn’t forget her. In 1946, they contributed over eighty works of art to a benefit auction held in Weill's honor. With the auction’s proceeds, she was able to live the last five years of her life in relative comfort. (Figure 18)

Figure 19. Berthe Weill Garden, Picasso Museum, Rue Thorigny, Paris

I took a pilgrimage today to visit the Berthe Weill garden next to the Picasso Museum on rue Thorigny, (Figure 19) it was lovely and will be even lovelier when the flowers start to bloom. Then I walked over to the 9th arrondissement, to 25 rue Victor Massé where a plaque commemorates Berthe Weill’s gallery and her commitment to young artists. (Figure 20)

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Figure 20. Plaque honoring Berthe Weill, 25 rue Victor Massé

Photo of Berthe Weill and Mrs. Bollag upon which the Moira Kalen drawing is based.